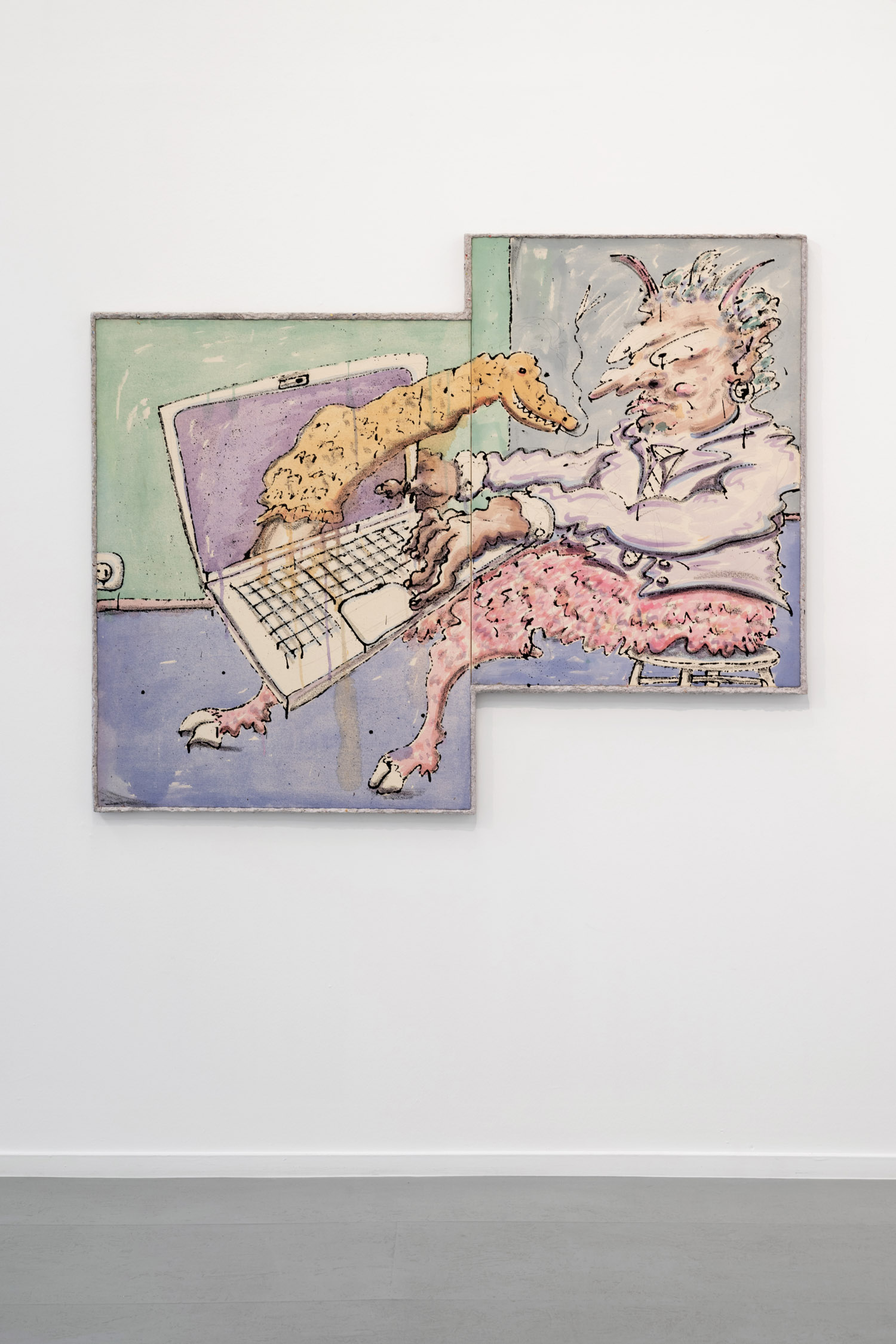

William Ludwig Lutgens (1991, Turnhout), two years after his last solo exhibition on Belgian soil, invites us into his world again, which has lately been populated by new and transformed archetypes. A man with devil ears and a tie stares before him while dragon-like hand puppets seem to conjure him. He embodies the hard-working, neoliberal achievement-subject that needs fantasies of success and money to avoid an overly harsh confrontation with reality.

Lutgens draws on Lacanian psycho-analysis and in particular that of Slovenian psychologist and philosopher Slavoj Žižek in his approach of this character and his fortunes. Žižek uses the term fantasy supplement to refer to the ways in which our imagination fills in the disturbing inconsistencies and gaps in reality. In Lutgens’ new drawings and paintings, this fantasy supplement is embodied by the Liegebeest, inspired by the BRT series of the same name from the 1980s. Whereas in the series the snake-puppet by the name of Liegebeest constantly lies to his own friends and the viewer, in this case the characters use the puppet to lie to themselves. The Liegebeest provides a narrative that helps the subject to successfully navigate his desires and fears while avoiding the painful incongruity of reality.

The Liegebeest thus incarnates the mechanisms of capitalist ideology, which portrays hard work and the supposed money and success that follow as the pinnacle of personal fulfillment. It is, however, this same ideology and the economic reality from which it springs, that generates its opposite today: the inactivity and passivity of anxiety, exhaustion, burnout.

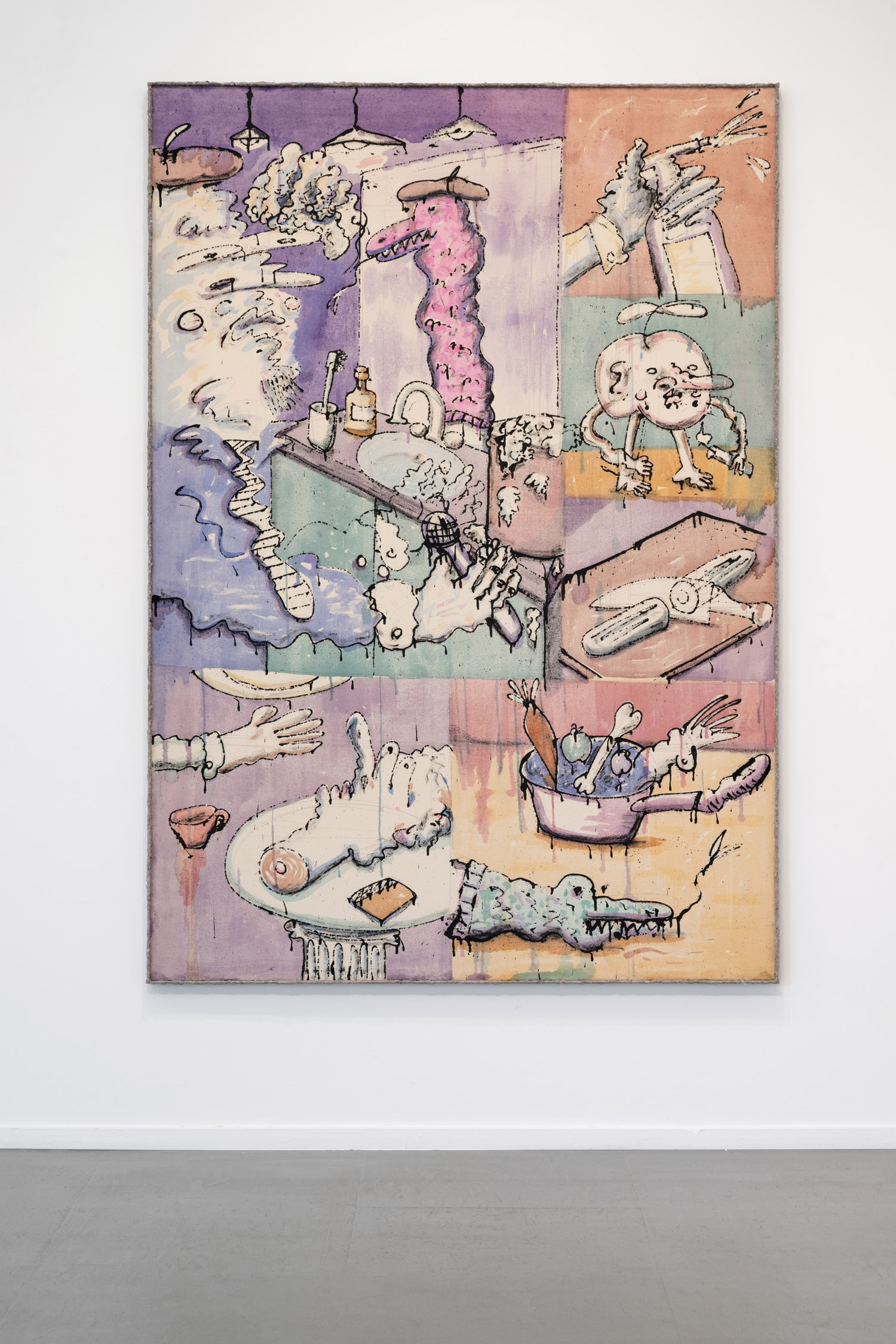

The characters cast in Fantasy Supplement suffer from this same fate. Lutgens approaches these tragic but familiar and relatable individuals at times with the necessary humour and mockery, at others with respectful mildness. In his first ever film Joy Sauce, lifeless characters are depicted who, in a constant struggle with themselves and their oppressive surroundings, try in vain to forge social and physical connections. In his paintings, Lutgens in turn evokes scenarios in which the achievement-subject seems forced to surrender to resignation and boredom. Thus, slowly but surely, the figure of the Flierefluiter is born.

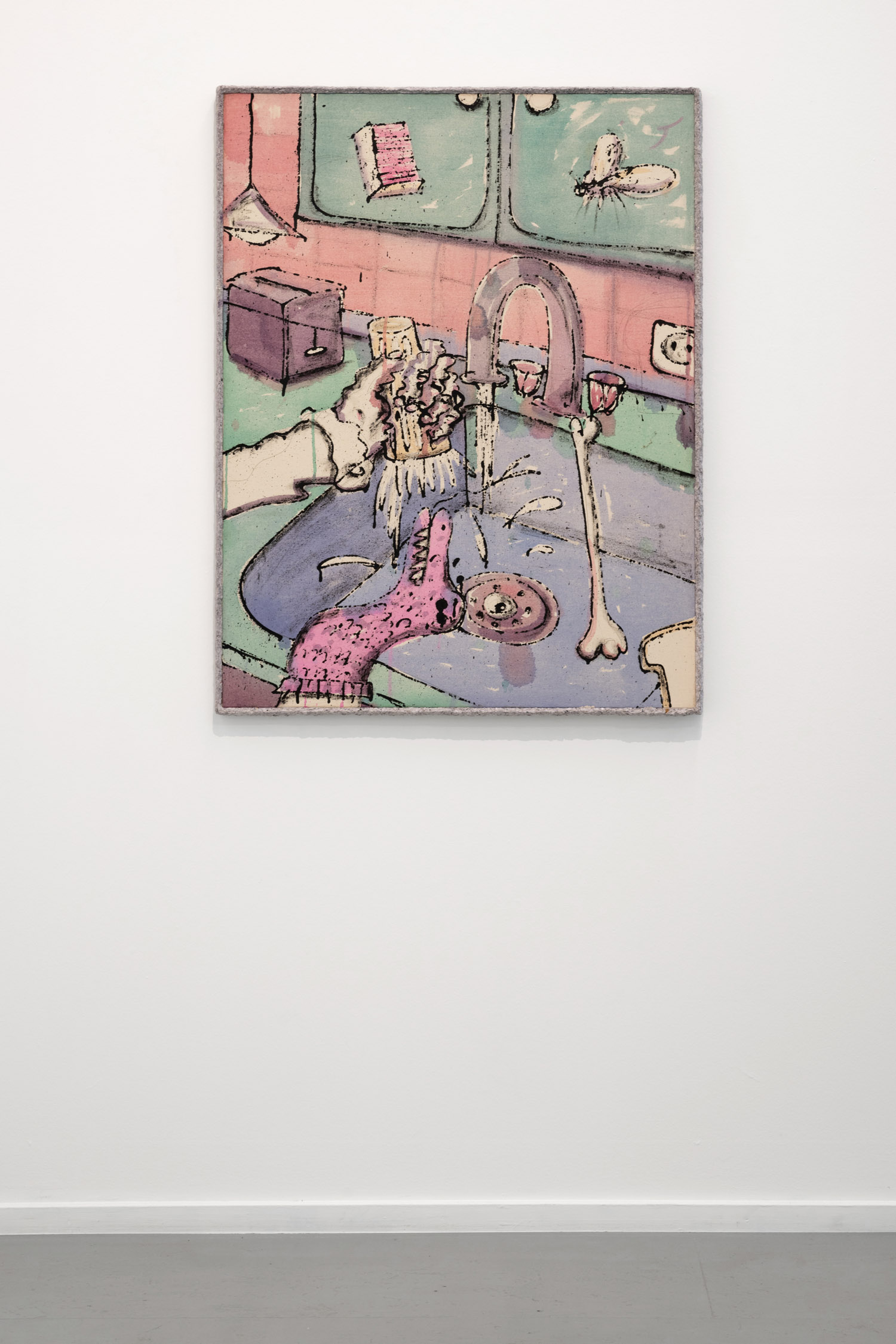

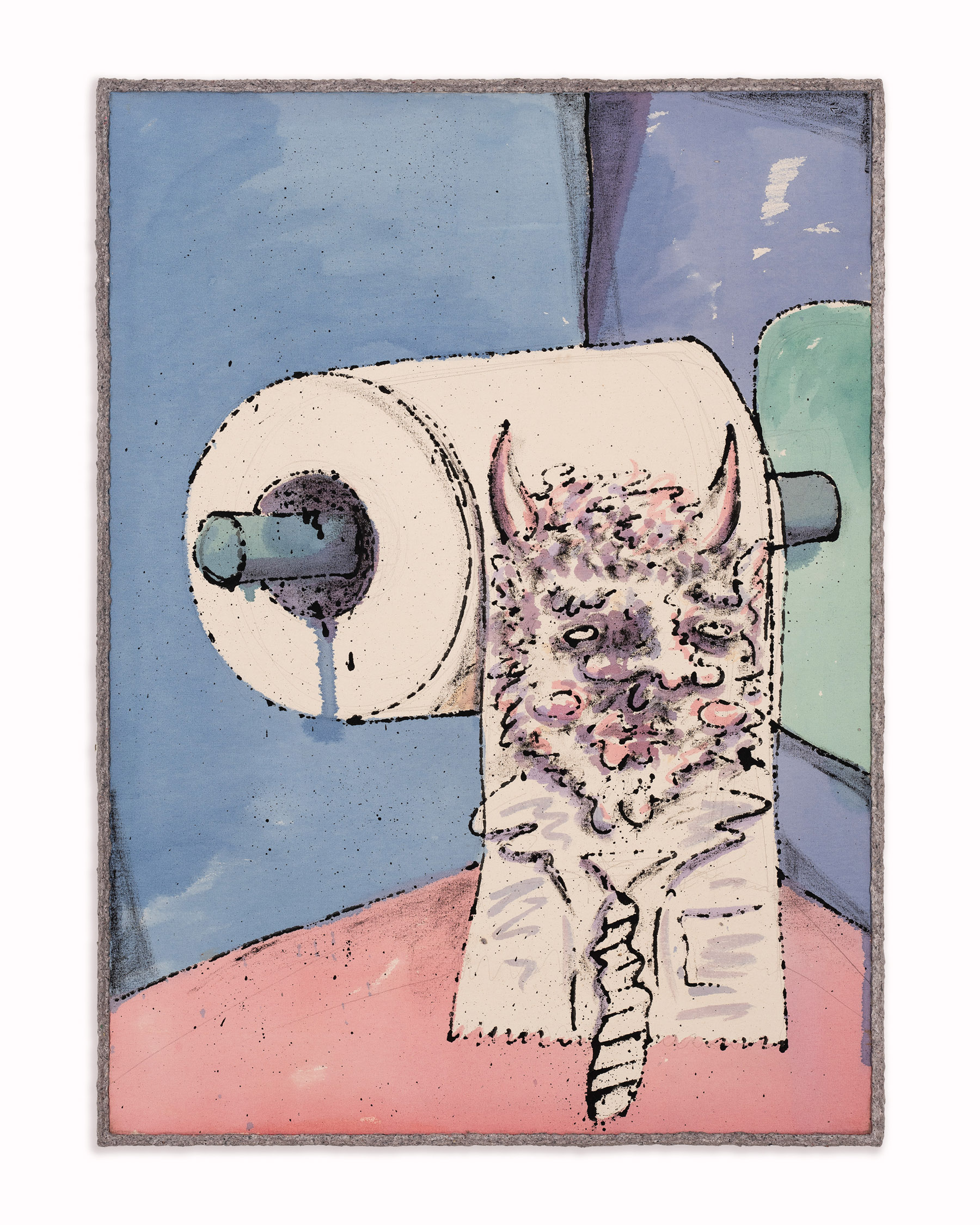

The Flierefluiter embraces sluggish life and manages to escape the constant pressure that drives the achievement-subject. He takes time to daydream, muse and contemplate. The Flierefluiter symbolises a plea for the recognition of idleness as a legitimate alternative to today’s relentless work culture. For him, the minimal activities of self-maintenance, such as cooking, going to the toilet, doing laundry, drinking and cleaning suffice

In the Flierefluiter’s alternative position lies the possibility of re-thinking the role of our imagination. His radical acceptance of unproductivity provides fertile soil in which the dream can sprout. In the dream, the creative power of our imagination manifests itself which, in sharp contrast to the Lacanian fantasy-supplement, can be a driver of movement, of change. It is precisely through slowness and tranquility, through watching and listening, through unproductive being and experiencing, that new worlds may be revealed.

The Flierefluiter also lurks in you and I. Let us welcome, rather than vilify him.