Artists: Yun Choi, Rashiyah Elanga, Eric Sidner, Nicholas Stewens, Stella Zhong

Exhibition title: Why Do I Know You So Well?

Venue: Deborah Schamoni, Munich, Germany

Date: June 22 – August 10, 2024

Photography: Ulrich Gebert, all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Deborah Schamoni, Munich

Summer shows tend to be light-hearted and experimental, and this one is no different. Featuring the works of five international artists, the exhibition seeks to examine how the concept of “escapism” can be helpful in describing new artistic strategies. A widespread belief in art’s utility for improving the world has led to a fixation on current events that obscures alternative qualities, origins, and methods. Against this background, escapism is not merely an escape from reality, but rather a maneuver of evasion and expansion, a form of disobedience and resilience. Elements from science and science fiction, along with playful recursions, pop and trash, are employed to create joyful openings—tunnels to an outer world that goes beyond the sometimes grim logic of day-to-day life, hinting at new possibilities for action.

For all their differences, the artists included here share a playful approach that pushes the boundaries of formal constraints. Their works often migrate across media: videos become objects, paintings expand into sculptures, everyday myths are overwritten with new narratives. Theatrical doublings, dilettantish appropriations and transformations—everything appears in flux.

Yun Choi (*1989) investigates collective “confusions” observed in public spaces and popular media in Korea. She traces the everyday myths and daydreams that often develop out of absurd socio-political phenomena. In capitalist Korean society, shamanism and animism remain pervasive; everything appears connected to everything. And yet these fluid meanings often clash with rationalized mundane existence, and collective experiences of historical oppression continue to influence the contemporary psyche.

These distortions resurface as multiheaded beings in Choi’s videos. Trance-like rituals, ghostly rave parties, and dramatic monologues sublimate and channel disoriented and repressed sensibilities.

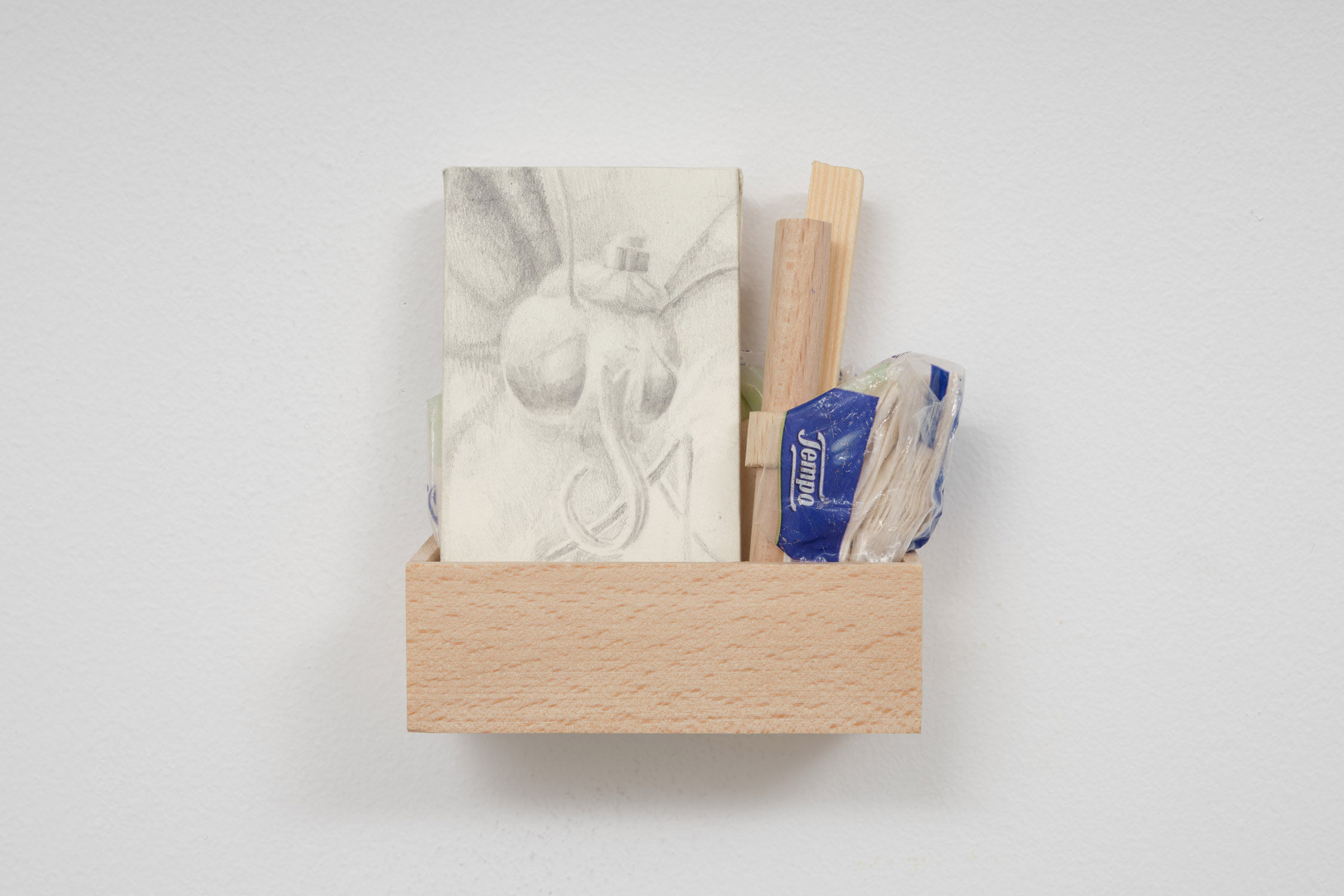

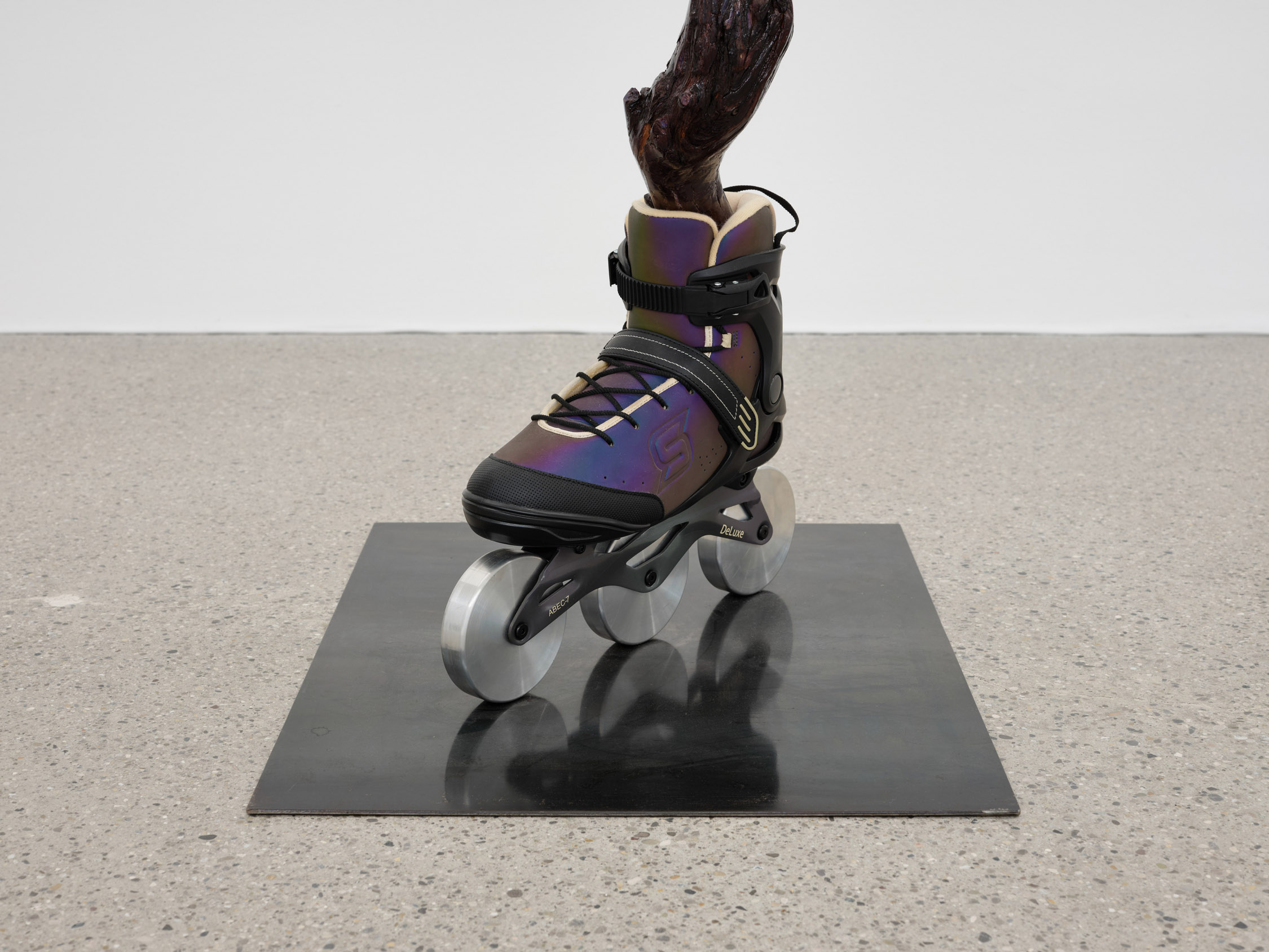

Yun Choi’s playful pop shamanism oscillates between digital and physical strategies. Matter is vitalized and animated. Sculptures can take on roles within videos or be extrapolated and materialized from the flow of images. Ancient trees may transform into grandmothers, powerful spirits appear on roller skates. An abstract painting, reminiscent of the Informel tradition, becomes part of this fluid play of transformations. It could symbolize the general “confusion” or even accelerate the growth of the mold that often thrives in the damp and decaying apartments of Seoul.

Rashiyah Elanga (*1997) develops their very own cosmos with their poetic narratives, which are grounded in scientific and mythological research. Science and myths, the Internet and Gen Z subcultures, teenage rituals and the cultural heritage of their Congolese family, all coexist in Rashiyah’s sparkling, transtemporal multiverse. Like dreams, her worlds are simultaneously self-sufficient, dialogical and constellative.

The video “Another Dream in the Troposphere” is a space odyssey. The protagonist’s journey tells of a struggle for humanity and peaceful coexistence in the Anthropocene. This adventure depicts the journey to self-love, from the exploration and experience of the sublime to introspection and connection with oneself. The story draws its initial inspiration from the Congolese astronomical programme Troposphere, founded by Jean Patrick Keka.

Lost in the beauty of this icy moon of Jupiter, Europa, the astronaut hoped to meet the unknown, but in the end she only met her own reflection. She realises that the magic of this place also lies within herself. Her difficult life on Earth made her forget her past glories; she remembered that her ancestors are not only human.

A new series of paintings and photo collages refers to Congolese music of the 80s and its influences. One particular reference is to the two famous rumba singers Mbialia Bel and Tshala Muana. They embody a femininity that Rashiyah Elanga admires and celebrates, but also a femininity that is very alien to them.

Stella Zhong (*1993) plays a distinctive role in our journey, with works that delve into the very essence of matter itself. Through her sculptures, she creates models that are finely tuned to both macroscopic and microscopic scales. She reflects, “When I think of atoms as the building blocks of matter, I think about how they encode histories and numbers that articulate relationships, and how our bodies are made of those same atoms.”

Zhong’s fascination with the embodiment of consciousness and emotion suggests that the interaction between our bodies and the environment—such as seeing and touching objects—involves a feedback loop between the quantum properties of the body and of objects. This feedback implies that consciousness possesses spatial and dimensional attributes.

Zhong develops objects, installations, and paintings in her studio with an experimental and playful approach. Rather than illustrating physical insights, she creates intriguingly unconventional objects that might also serve as proposals for a new reality.

Like strange fruits from the tree of knowledge, these modern objects lead a liberated existence, detached from any functional context. Confronted with Zhong’s works, I feel like the ape encountering the monolith in 2001. I would also venture to say that such galactically real objects have rarely been seen since Isa Genzken’s Hyperbolos.

Choi and Elanga’s material consists of terrestrial and extraterrestrial myths, which they seek out, travel through, and invoke in their work. Zhong, by contrast, examines the myth of science, which she uses to immerse herself in an exploration of the materiality and energy of objects. Meanwhile, Stewens and Sidner are primarily concerned with the visual and linguistic worlds of art, which they investigate in terms of syntax and transparency.

The art of Nicholas Stewens (*2000) pushes the boundaries of the profession. His work is sophisticated, intricate, and meticulous, characterized by a capricious and suspenseful style often enriched with enigmatic allegory. There are parallels to Mannerism, a style that has been widely studied and interpreted. Ultimately, both movements challenge all-too wise, all-too white, predominantly Eurocentric conventional norms.

The fractured obtrusiveness of Stewens’s pictures testifies to an affirmative engagement with painting, a discipline recently maltreated by AI. Similar to their computer-generated counterparts, Stewens’s visual motifs may initially seem mundane or anecdotal. However, beneath this surface lies an implicit violence, possibly unaware of its own antagonistic nature.

Stewens intertwines painting and sculpture, allowing them to extend and complement each other. The inherent violence of their depicted content is unleashed on a new level with elaborate, exaggerated forms. The process embodies a form of spiritualization that emerges from, but also contrasts with, their essence.

There stands a poor little lamb with a crutch and the seal of quality already affixed; we hardly see the evil and oversexed cannon, as a stubborn silencer is pushed prominently into the picture and makes war thick and silent, etc. Lastly, a silent drum set presents itself, perhaps for the virtual acting-out of subliminal aggressions?

Eric Sidner (*1985) has already attracted attention with three enigmatic exhibitions at Deborah Schamoni. His most recent works are large and fragile, made of glass and porcelain. Their precious materials and exquisite craftsmanship suggest relics from a distant, unfamiliar era. Nevertheless, the timeless quality of the sculptures contrasts with other elements they incorporate, including props or set pieces from our own everyday culture.

The sculpture confronts us as a whole, resembling an extraterrestrial automaton eager to communicate. At its center is a large, oyster-like model of teeth with exposed molars, adorned with flickering heart-shaped flames? Then there are the earthlier suggestions: a glass sphere crowned by a playful cowboy hat containing another sphere in red. Is it an eye? A clown’s nose, perhaps?

Sidner’s wayward formal idiom comes across to us as fragmented. He describes it as an attempt at speech ensnared. And so this mouth will not be speaking today. The sculpture suggests a syntax in which its elements resemble characters from a foreign alphabet or syllables poised to be spoken. It is not a matter of deciphering an intrinsic truth; rather, our act of interpretation animates these static “signs.” After all, reading revives an organism! Thus, sculpture becomes a reality shaped by signs; it serves as a vessel that both formulates messages for us and withholds them at the same time.

Ultimately and regarding the question “Why Do I Know You So Well?” the following should be noted…

Whence it comes, to me unknown,

The familiarity deeply sown,

Is it grandmother I see in the tree?

Europa, a love mysterious to me?

Grandiose mathematics giving birth,

As a body feeling an idea’s worth?

As painting penetrating lambs so deep,

As a heart of glass, prone to shatter, weep.

Text: Werner von Delmont (translated from German)