Artists: Laetitia Badaut Haussmann, Nick Oberthaler, Hugo Scibetta

Exhibition title: What Kind Of Bird Is This?

Venue: LEVY.DELVAL, Brussels, Belgium

Date: June 4 – July 9, 2016

Photography: images copyright and courtesy of the artists and LEVY.DELVAL, Brussels

How to stay aware of our direct surroundings when this ability is taken care of by the constant interconnectivity, the free online dictionaries and the cloud backups? These media tend to be more trusted than the sheer observation of the milieu.

« What Kind Of Bird Is This? » Elementary, my dear Watson… Beyond the detective’s cult phrase -so British, Watson is also a computer system able to answer to a multitude of questions, if they’re asked in plain language. [1] This IBM-developed A.I. was programmed to answer to the Jeopardy TV game – game that the computer beat three times. So, if Watson is asked « What Kind Of Bird Is this?, do you think it will actually be able to answer?

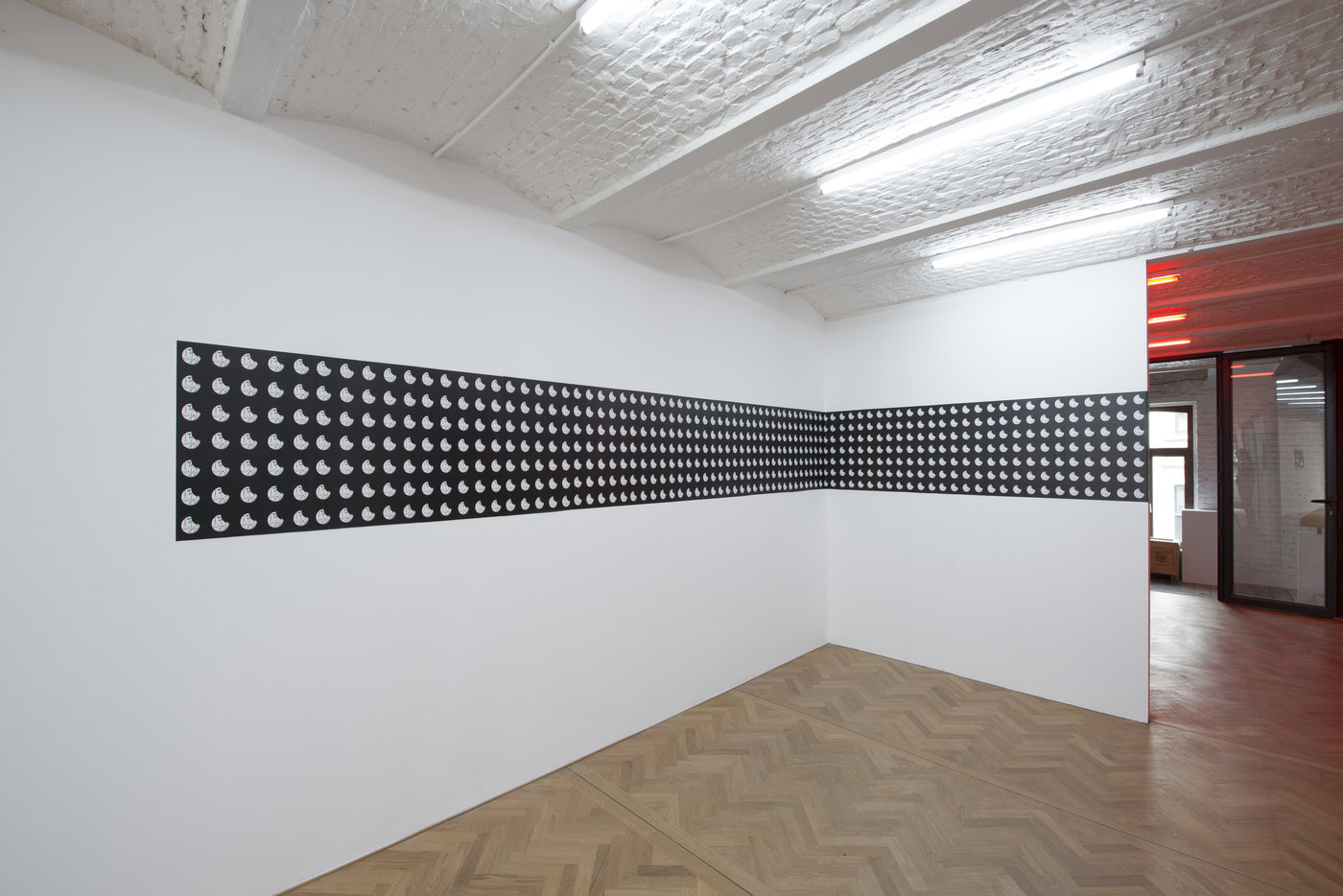

« I can See The Whole Room And There’s Nobody In It » [2] This the message on Roy Lichtenstein’s painting that Nick Oberthaler is appropriating; a character can be seen looking through a peephole and telling that the whole room can be seen, but, not without humour, that there’s no one to be seen! So where are we? While repeating this inquisitive gaze to the point it becomes a reoccurring question and while the information is constantly broken down to pieces, the Austria-born painter questions our mere viewer position and the very place of the exhibition. The round shaped window recalls the eye as well as the camera. What if the emptiness that Lichtenstein puts forth, is nothing more than a focal length issue? One eye has to be closed, it’s a way to constraint the gaze to the space – and the opposite as well.

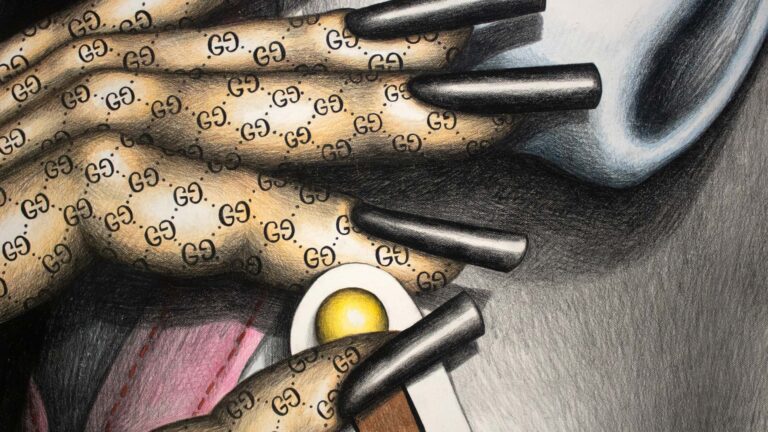

The same kind of gap operates in Hugo Scibetta’s monochromes series. He’s set a process where each time he has to use his cell phone, he has to take a picture. Then, the black mirroring screen of the phone becomes the front of the painting, while the picture of the environment becomes the edges, and thus the depth. It’s not our point of view that is depicted – or imposed, but the one of a communication device. The result is a monochrome (made with a thick glazing) that creates an alter-space: the reflection of a landscape, both past and present. Moreover, Hugo found the title of the show while strolling on the Internet. These modern hikes and solitary daydreams are filling up our phones, computers and our beloved cloud with datas and meta-datas. That’s how he realized the standardization of exhibitions photographs, as seen on Contemporary Art Daily for instance. These photographic reports generate an ubiquity, that is as enjoyable as it is deceptive. The marks of the typical exhibition photographs canons are erased by Hugo Scibetta until the depicted object is not recognizable anymore. This intervention is brilliant because the blurring process prevents any further reproduction. The new composition is so vibrant that a camera cannot properly focus. Thus, Hugo Scibetta stops the images and colors thieves.

Hugo’s chromatic compositions are resonating with Nick Oberthaler’s colored neon lights that are creating pictorial ambiance. Made with the complicity of the two other artists, this intervention on the lights is as heady as an easy listening tune. The famous daylight neon – the white cube’s partner in crime – when it’s tinted, is now dividing and altering the space. Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann’s intervention is in the same vein. As efficient as it is simple, she asked the gallerists to let the windows wide open during the opening hours. This spontaneous gesture allows the green leaves of the palm tree to be an inherent part of the show, while the outside hum becomes its constantly changing soundtrack. As far as the eyes can see, they are seduced by the interaction between the whiteness of the walls, the tinted industrial neon lights and the blue sky/green vegetation, that was hidden. In a gallery space freed of its usual compartments, sculptures get loose and soft while showing their ambivalence. Indeed, Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann designed the posters of the show and printed them on floating silk scarves; the communication supports become actual artworks that can be worn during Summertime. This play between the categories is also at stakes in the sentimental sculpture L’amour est plus froid que la mort: the bronze and sunset colors of the textile sculpture are blurring the frontiers between artificial and natural lights. The sleeping twinkling volume is a made to measure installation is hanging from the ceiling to stress upon its actual materiality. The most present piece in the gallery space, the twisted piece of fabric is embodying the knot that mixed and contradictory emotions can sometimes produce. It derives from the remote memory of reading Genet’s Querelle de Brest.

Now, a bit further footprints left by Hugo Scibetta mark the end point of the visit. Casted in shape memory foam, they are combined with an augmented reality device that reveals a whole character with the help of a smartphone camera. An actual ghost. Or maybe a breath passing through a space now open to the outside. The word « ghosting » may evoke at first a mere disappearance but it takes a more precise meaning here.

It is a brand new social trend that implies to literally vanish from social networks and to become invisible on the Internet; it’s also used when a broadcasted image is replicated and superimposed. It’s a « bug » that can be the visual equivalent of the « dejà-vu »; a disturbed image associated with a kind of intuition or elusive presentiment.

– Arlène Berceliot Courtin, May 2016

[1] Also called « natural », that is the human language

[2] I Can See the Whole Room!…and There’s Nobody in it!, Roy Lichstenstein, 1961, huile et graphite sur toile, 121,9 x 121,9 cm.

[3] A pastiche of US noir movies, Love Is Colder Than Death (1969) depicts a tricky love triangle relationship. It’s R.W. Fassbinder’s first feature film.

Nick Oberthaler, Untitled, 2016. Posters, Variable dimensions

Nick Oberthaler, Untitled, 2016. Posters, Variable dimensions

Nick Oberthaler, Untitled, 2016 (detail). Posters, Variable dimensions

Hugo Scibetta, IMG_20160501_190334, 01/03/2016 05:38 PM, 45, 364932 5,594669, 2016

Print on canvas, Acrylic paint, Resin, 50×29 cm

Hugo Scibetta, IMG_20160501_190334, 01/03/2016 05:38 PM, 45, 364932 5,594669, 2016

Print on canvas, Acrylic paint, Resin, 50×29 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, Whatkindofbirdisthis_1_silkposter, 2016

Digital print on silk scarf, 140×170 cm

Hugo Scibetta, Empreintes, 2016, Memory shape foam, digital file

Hugo Scibetta, IMG_20160414_152130, 14/04/2016 3:29 PM, 15, 188883, 5,705712, 2016

Print on canvas, Acrylic paint, Resin, 50×29 cm

Hugo Scibetta, IMG_20160414_152130, 14/04/2016 3:29 PM, 15, 188883, 5,705712, 2016

Print on canvas, Acrylic paint, Resin, 50×29 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm

Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann, L’amour est plus froid que la mort 3, 2016

Steel, Aluminium, Velvet, Foam, Plexiglas., Approx 172x285x143 cm