Artists: Kasper Bosmans, Edith Dekyndt, Ceal Floyer, Janice Guy, Gary Indiana, Erika Keck, Izhar Patkin, Nicolas Provost and Hans Witschi

Exhibition title: Till I Get It Right

Curated by: Tim Goossens

Venue: LABOR, Mexico City

Date: July 10 – September 11, 2015

Photography: Ramiro Chaves, images courtesy of the artists and LABOR, Mexico City

Till I Get It Right brings together the work of an intergenerational group of artists- almost all of them exhibiting for the first time in Mexico- that calls out our modern day perpetual obsession with craving achievements and positive results. Till I Get It Right is not merely a gathering of works and artists, but a stand against the dictatorship of perfection; a plea for going through life by embracing the punches: this is an exhibition about persistence, repetition and the beauty of failure.

The title of the show is borrowed from Ceal Floyer’s seminal sound work, in which the first sentence of a Tammy Wynette country song in looped eternally. Greeting the visitor in an empty room upon arriving at the gallery, the voice in the pop song declares she will not give up her quest until she finds true love. She is stuck in a loop of either making the same mistake over and over again, or perhaps rather brave enough to not be giving in to failure, steadily believing in life and love.

Not only love, but life in general is always in flux, and representative of this notion is Edith Dekyndt’s Ground Control/Major Tom, a balloon as wide as a human body, which floats freely through the exhibition space. Just like in our lives, the movement is dictated by mostly random factors, in this case temperature, currents and the movement of the visitors.

Perfection as something artificial is symbolized by Nicolas Provost’s looped video of a surfer, catching and riding a perfect wave. He floating in an eternal rush of man meets nature, a joyful celebration of freedom. A closer look reveals however that the image is created from stock footage and edited together to create a picture-perfect illusion, a Hollywood dream that can never be obtained, but in a best case scenario can serve up inspiration and ambition in the real world.

Seriality in order to defeat the notion of the ultimate portrait is a tactic employed by Janice Guy in her silver-gelatin prints from the late 1970’s. We may assume some sort of editing has happened before sharing these photographs with the public, but what a viewer takes away from them is an honesty in sharing and documenting one’s own body. The portraits encourage us to not overthink when wanting to take action, and instead of being paralyzed by reflecting one can grow in life and through action and experience.

The painter Hans Witschi is also known for working in series, and included in the exhibition is a selection of nine variations of the same image, based on an NY Times photo of a young boy drawing or perhaps merely day dreaming. The seriality reduces the strain of the notion of achieving “the perfect painting”, a Leitmotiv that has appeared as early as 1831 in Honore de Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece. The fable accounts about a painter working for over ten years on a portrait, only to find out upon finishing it, that he has created a confused mass of color and jumble of lines. By drawing the same figure over and over, Witschi seems to be claiming there is not one right way of representation. Through the seriality the fantasy of the perfect painting get’s destroyed in order to free the way for multiple voices and interpretations.

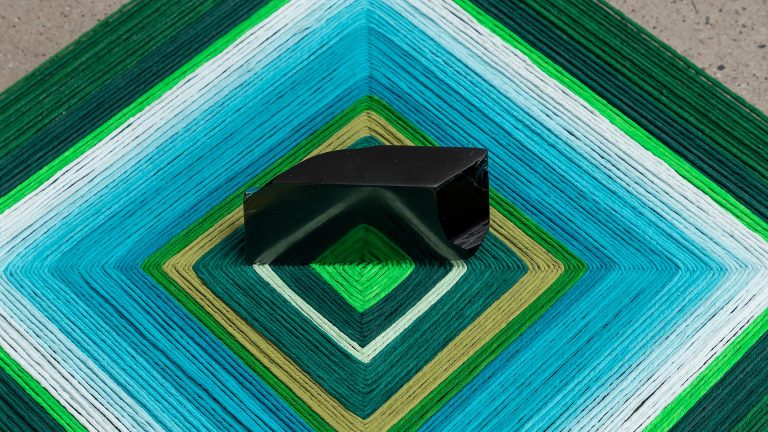

A playful way of tackling the fetichism of the ideal painting is Till You Get It Wrong, Erika Keck’s painterly interactive installation. Keck’s works start with the traditional formal notions of a painting as an anchor point, but then quickly depart from there, interjecting a sense of play and inquisition by making non-traditional use and misuse of traditional painting materials. In this new work, made for the exhibition, the visitor is invited to change and recreate her painting until the ultimate “perfect” painting is achieved; an illusion with irregular pieces of acrylic paint that have been highly layered and reworked, creating multi-textured surfaces and structures that straddle the line between a painting and a sculpture.

Related to the obsession over the ultimate painting is the research undertaken by Kasper Bosmans into the archetype of the pre-renaissance mandorla motif. On view here is the first series of an expanding database on mandorlas, all from Italian frescoes that are found in public buildings. Every painting is accompanied by the logo of the town the shape can be found in. The oval shaped aureole has accompanied representations of religious figures since early medieval art. In six separate and non-hierarchical studies the artist dissects the evolution of the oldest motif in the exhibition, and formulates thus a proposal about the most ideal halo for and its genesis.

Strike, a collaged photograph by Gary Indiana shows a group of mineworkers manifesting for their labor rights. Instead of demands, their pickets show futile complaints and whining personal statements. Much like social media once captured hopes as a platform for our modern society to entice change and gather people for action, all too often it has become a platform for venting our petty sorrows from behind our desks and cell phones, keeping us from actually taking to the streets and demand fundamental change.

The illusion of perfect beauty is being blurred in Izhar Patkin’s veil of a vintage image of a beauty queen. The anonymous woman was elected Miss America, and she appears before us as a ghost, created with a unique printer, which took the artist over a decennia to construct. The pageant contest might have been a real event, but the portrait on the tulle is a ethereal presentation of the notion of beauty throughout time, which similar to political and social freedoms changes throughout time, is in a constant flux.

– Tim Goossens

Ceal Floyer, Till I Get It Right, 2005

Izhar Patkin, Beauty Queen, 2005

Hans Witschi, Ohne Titel (Zeichnender) | Untitled (Boy Drawing), 1998

Kasper Bosmans, Mandorla: Fontanella, Varese, Volpedo, Paruzzaro, Loreto Aprutino, Como, 2015

Janice Guy, Untitled (Rattan Chair. Triptich), 1979

Erica Keck, Until you get it wrong, 2015

Gary Indiana, Strike

Nicolas Provost, The Perfect Wave, 2014

Janice Guy, Crying, 1979