Artists: Allora & Calzadilla, Candida Alvarez, Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.), Iván Argote, Ricardo Brey, Gisela Colón, Débora Delmar, Teresita Fernández, Ignacio Gatica, Lucia Hierro, Alfredo Jaar, Anuar Maauad, Carlos Martiel, Joiri Minaya, Gabriela Salazar, Yoab Vera, Valeria Tizol Vivas

Exhibition title: Terms of Belonging

Venue: GAVLAK, Los Angeles, US

Date: October 22 – December 10, 2022

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and GAVLAK, Los Angeles

GAVLAK is proud to present Terms of Belonging, an intergenerational exhibition of Latin American artists featuring Allora & Calzadilla, Candida Alvarez, Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.), Iván Argote, Ricardo Brey, Gisela Colón, Débora Delmar, Teresita Fernández, Ignacio Gatica, Lucia Hierro, Alfredo Jaar, Anuar Maauad, Carlos Martiel, Joiri Minaya, Gabriela Salazar, Yoab Vera, and Valeria Tizol Vivas. The exhibition opens on October 22 and will continue through December 10, 2022. A closing panel moderated by curator Susanna V. Temkin, PhD. will take place on Saturday, December 10, 2022 and Valeria Tizol Vivas will perform her durational piece Mejunje: la encendida..

The word “belonging” conveys an effortless kinship: a natural affinity between like and like. The imposition of the word “terms,” however, shatters this ideal and serves to remind that communities are also forged through selective exclusions. By focusing solely on conceptual practices in the work of Latin American artists, Terms of Belonging asks what it means for an artist to refuse the call for “positive” representation on behalf of a marginalized community through established artistic conventions and forms. Though this pressure to produce and/ or represent on behalf of a larger cultural identity is not isolated to artists of the Latin American diaspora, Terms of Belonging proposes a framework for Latin American art that does not hinge on nationality or ethnicity. Like the contentious term “Latinx,” the exhibition signals the need to expand beyond antiquated categories of belonging while acknowledging the ways in which these new and supposedly more inclusive terms are themselves rooted in specific and localized definitions of Latin American experience.

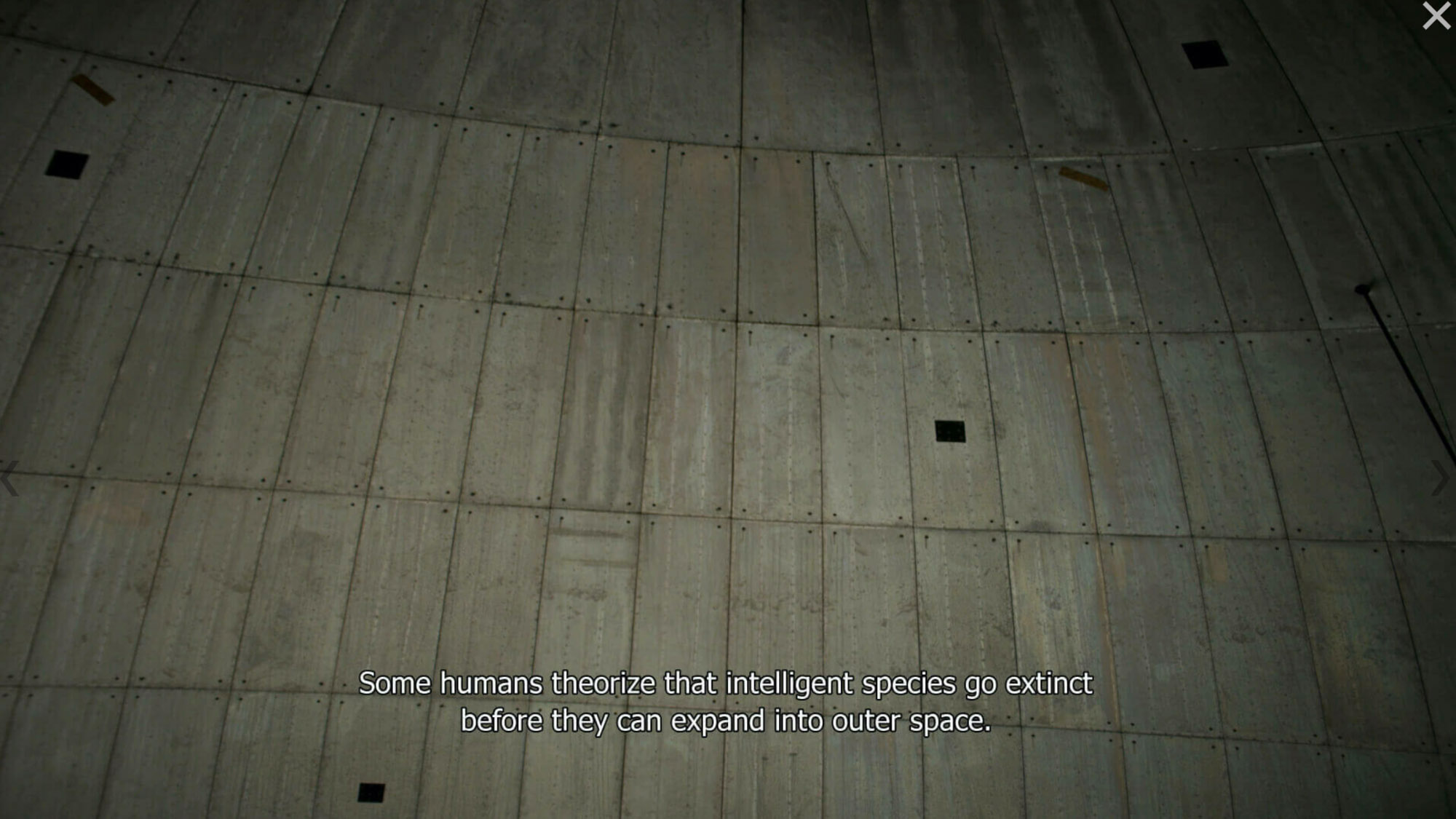

Like the broader conceptual and minimalist traditions to which they belong, the works in the exhibition do not comprise a rejection of figuration, or identitarian concerns entirely. Instead the inclusion or allusion to real bodies constitutes an acknowledgment of the reductive nature of individual and collective identity, and a desire to speak beyond the constraints of the self. In publicly subjecting his own body to a period of chemically induced insentience, Carlos Martiel demonstrates the fundamental impossibility of communicating the depth of interior states via external systems. Joiri Minaya in her Container series depicts tableaux of women outfitted in floral bodysuits which paradoxically camouflage them amongst staged “natural” environments, registering the contemporary effects of primitivizing narratives that conflate Black and Latina women with nature. Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.) capitalizes on the ubiquity of mass media in everyday life, tapping into and satirizing the craving for meaning that has historically spurred colonizing cultures to fabricate (and impersonate) “native” spiritual guides. In a striking video composition that features no human subjects at all, Allora & Calzadilla produce a vision of Puerto Rico defined by structuring absences: the Taíno people who have become the subjects of the island’s pre-contact origin myths following their eradication through colonialism, and the ruins of the agricultural and petrochemical industries that abandoned the island after extracting its resources.

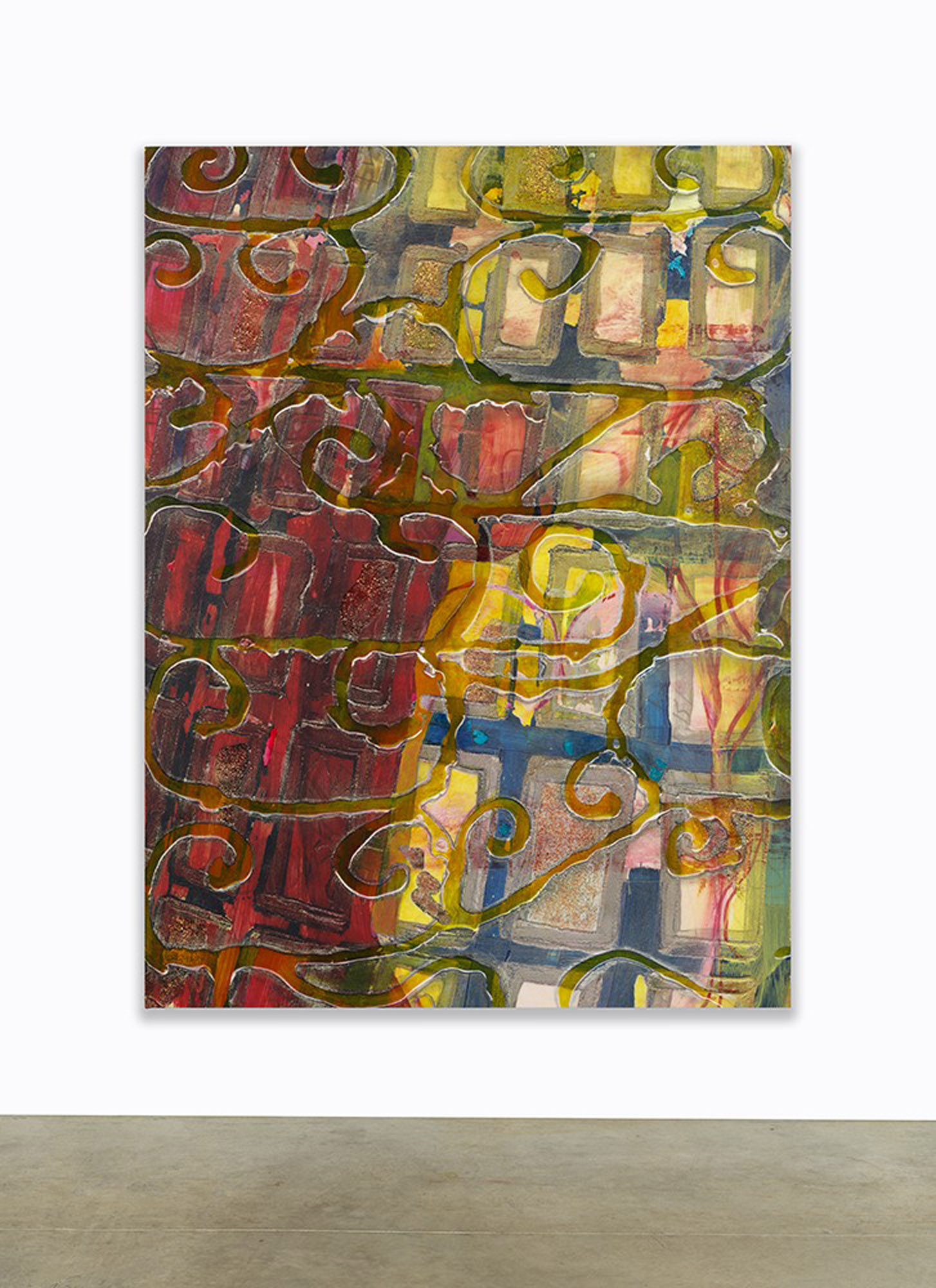

Through charred compositions of burned and cut paper that grimly approximate the carbon traces left by dead vegetation, Teresita Fernández likewise traces the lingering effects of cut-and-run colonialism, on Puerto Rico’s compromised ecosystems. Similarly, the bright, kaleidoscopic panes of Candida Alvarez’s acrylic abstraction evoke the fragility of man-made structures in the face of ever-intensifying natural disasters due to climate change. The forms which emerge from her canvas directly reference rejas, the decorative iron grilles that are placed over home windows throughout Latin America. In Puerto Rico, these grilles protect against tropical storms; here, however, they appear in fractured, sunken relief, ominously signaling vulnerability instead of fortification. A new work by Gabriela Salazar recapitulates a day-long participatory art experience staged for the Climate Museum in Washington Square Park, New York, in which Gabriela Salazar compelled the public to consider their potential as agents of climate justice by offering a surrogate of her own home to be dismantled. Over the course of one rainy day, passersby were invited to take a piece of a delicate structure created from paper casts of the windows of Salazar’s apartment, propped into place with sandbags obviously incapable of preventing the sculpture’s dissolution. Here she presents a re-fabricated element of that original installation that functions as a desire for preservation in the face of climate-catastrophe.

In an installation combining the sterility of minimalist readymades with the preciousness of hand-crafted facsimiles, Débora Delmar examines the exalted place to which the avocado has ascended in global food systems and the impact the increased demand has had on its primary importer, the state of Michoacán, Mexico. In a series inspired equally by Donald Judd’s minimalist “stacks” and the food cultures of corner bodegas endangered by gentrification, Lucia Hierro produces reverse readymades by creating meticulous replicas of glossy, mass- produced packages of salty snacks. In luminous monoliths that are at once atavistic and imposing, Gisela Colón resists dominant interpretations which posit minimalist sculpture as austere and impersonal. Layers of sediment harvested from formative sites in the artist’s life support a glittering pinnacle, becoming stacked totemic structures forged in a crucible of pulverized bullets and cosmic dust.

American minimalist sculptors in the 1970s often chose to present and preserve ordinary industrial materials in a pristine state; comparatively, Yoab Vera’s modular abstractions in scumbled oils and concrete approximate the living quality that these substances take on as they decay. Similarly, charcoal is the product of human intervention in a process of controlled entropy, Ricardo Brey’s mixed media assemblages stage baroque encounters between manmade flotsam and organic jetsam; delicate chains adorn a deep blue pedestal for a slender, bleached white bird skull that achieves its status as an objet d’art only through the animal’s demise.

As a genre uniquely concerned with thwarting death by visually securing the subject’s immortality, memorial sculpture often resorts to calcified neoclassical formulas designed to project power even from beyond the grave. Anuar Maauad works with the literal refuse of this industry, appropriating the plaster molds of cast bronze sculptures rejected by their commissioners for their failure to produce a desired immortalizing effect. These molds, presented themselves as sculptural works by Maauad, appear as monstrous, faceless golems embodying the horrors that the heroic idealism of memorial sculpture is meant to conceal. In the work of Iván Argote, the Romantic notion of the ruin as a site where hubristic culture is reabsorbed into nature is updated for the ongoing project of postcolonialism. By seizing on a worldwide tide of resistance resulting in the removal and destruction of monuments to slavers and colonizers, Argote, in a recent body of work, proposes that these toppled sculptures be repurposed as planters for local flora. He not only presents these proposals as artworks but has been actively engaging in an outreach campaign with the goal of manipulating news outlets into believing these acts of iconoclasm have already taken place, baiting contemporary political regimes into revealing their own investments in these monuments to inequity.

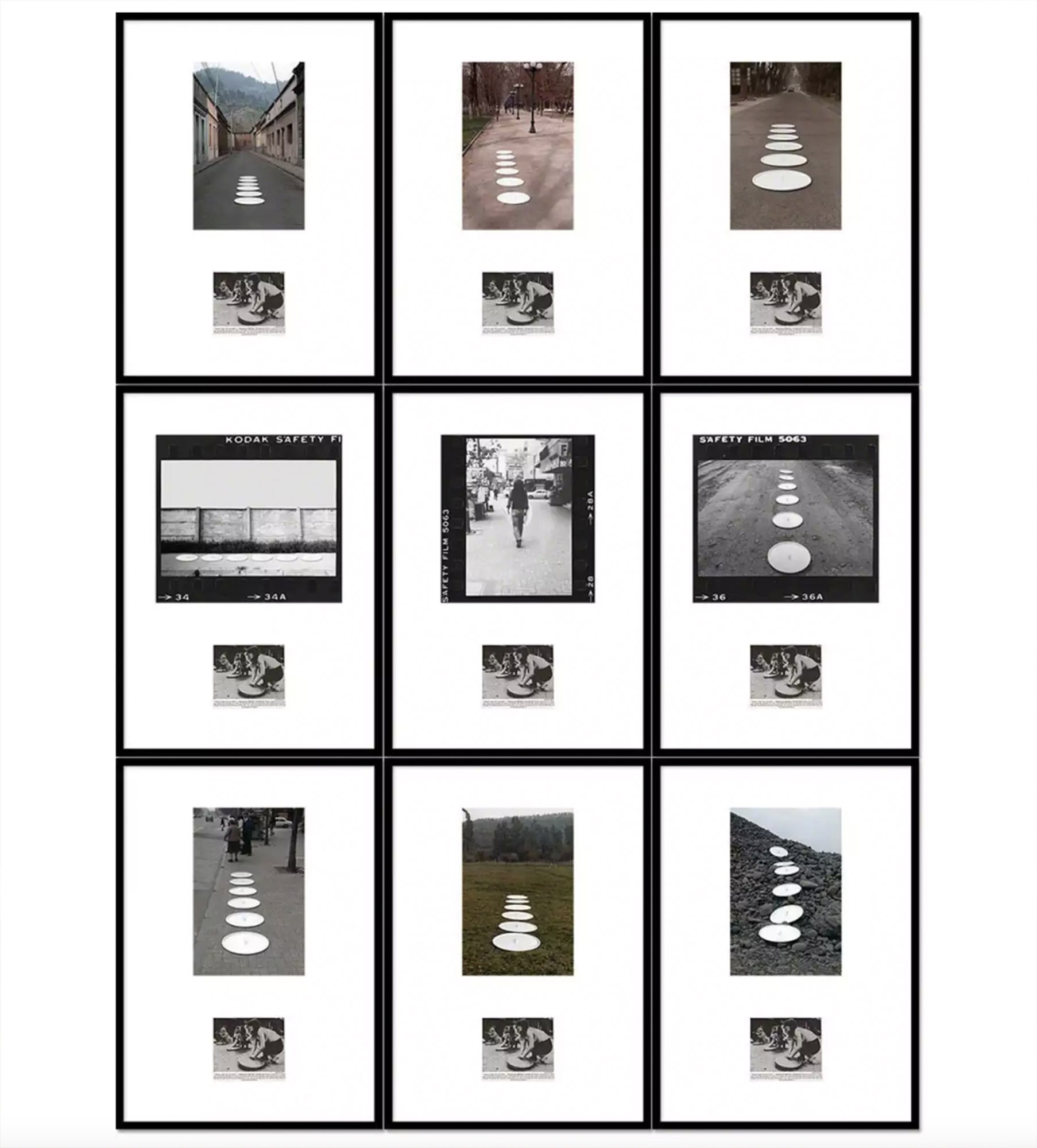

The dangerous challenge of marking and confronting a violent political regime is assumed by two artists in the exhibition whose respective careers bookend the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile. Inspired by Irish republicans’ use of trash can lids as noise-making tools of resistance, Alfredo Jaar in 1981 studded the streets of Santiago with them in an act of defiance that he could claim as a simple aesthetic exercise. By exhibiting documentation of the work alongside newspaper clippings chronicling the actions in Belfast, Jaar established the significance of this gesture only after he had completed it. Ignacio Gatica demonstrates the enduring significance of Jaar’s hijacking of the strategies of mass media propaganda for the next generation of Chilean artists by engaging participants with an interactive circular LED display that monitors the stock price of major corporations in real time. By swiping specially programmed cards through a digital reader, visitors trigger the interjection of street poetry into this capitalist recitation, asserting the potentiality of protest in both physical and virtual realms.

Through their work, these artists transcend the negative formations produced by an identification forged in shared traumatic experience and affirm the artist’s power to create radical forms and action in response to an oppressive market which seeks to fix, delimit, and categorize artistic output based on identatrian social constructions.

Terms of Belonging is organized by Efrain Lopez.

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Terms of Belonging, 2022, exhibition view, GAVLAK, Los Angeles

Ignacio Gatica, Stones Above Diamonds – Ticker Version, 2022, 56 x 56 in, 142.2 x 142.2 cm

Jose Alvarez (D.O.P.A.), In Perpetuity Through The Universe, 2002, 5 Channel Video, Digital SD Video

Yoab Vera, Calendarios_Varieties of Presence #SEPTIEMBRE, 2022, Oil-stick, concrete and acrylic on canvas and linen, 77 x 70 x 1 in, 195.6 x 177.8 x 2.5 cm

Ricardo Brey, Osain, 2012-2021, Mixed media, 12 1/4 x 8 1/2 x 23 1/4 in (31 x 21.5 x 59 cm)

Lucia Hierro, Rack – Takis, 2021, Digital print on brushed nylon, foam, and powder- coated aluminum, 144 x 15 1/2 x 4 in, 365.8 x 39.4 x 10.2 cm

Allora & Calzadilla, The Night We Became People Again, 2017, Digital HD Video, 15:07

Gabriela Salazar, Primary Residence (Low Relief for High Water), 2022 Water soluble paper, sandbags, 69 1/2 x 84 x 7 1/2 in, 176.5 x 213.4 x 19.1 cm

Gisela Colon, Totemic Structure (Piedras Contra Balas, Calcio de Luna), 2022, Monolith form composed of aurora particles, stardust, cosmic radiation, intergalactic matter, ionic waves, organic carbamate, gravity and time, over bullet- resistant lucite base containing layered matter, from bottom to top: pulverized bullets, Puerto Rico red earth (fango Borinqueño), Western desert sands, cosmic dust, 87.5 x 9 x 9 inches

Debora Delmar, Where Do Avocados Come From? (Westlake AR- 49BG), 2020-2022, Westlake AR-49BG refrigerator with cooling off, glazed ceramics, wood carvings, cop-per, 81.9 x 54.1 x 32 in, 208.03 x 137.41 x 81.28 cm

Alfredo Jaar, Telecomunicacíon, 1981, Suite of 18 digital, prints in 9 frames, Framed, each: 34.25 x 25.75 inches (87 x 65.4 cm)

Carlos Martiel, A donde mis pies no lleguen (Where my feet do not reach), 2011, Digital Video, 9:14

Teresita Fernandez, Puerto Rico (Burned), 2022 burned and cut paper, 21.75 x 29.5 inches, 55.2 x 74.9 cm, 22.5 x 30.25 x 1.5 inches (framed) 57.2 x 76.8 x 3.8 cm

Teresita Fernandez, Puerto Rico (Burned) 8, 2022 burned and cut paper, 21.75 x 29.5 inches, 55.2 x 74.9 cm, 22.5 x 30.25 x 1.5 inches (framed) 57.2 x 76.8 x 3.8 cm

Joiri Minaya, Container 7, 2015-2020, Photographic Print, 60 x 40 in (unframed), 152.4 x 101.6 cm (unframed)

Anuar Maauad, Terror 4, 2016, Plaster, metal wire and bronze, 85 7/8 x 33 1/8 x 15 in 218 x 84 x 38 cm

Ivan Argote, Etcétéra – en couvrant avec des miroirs Francisco de Orellana le soi-disant découvreur de l’Amazonie, 2016- 18, Framed C-print, 63 3/8 x 63 3/8 x 2 in, 161 x 161 x 5 cm (framed)

Ivan Argote, Etcétera- Bust, 2021, Mirror polished stainless steel, corten 81 1/2 × 42 15/16 × 31 1/8 in, 207 × 109 × 79 cm

Candida Alvarez, Prepare, 2020-2021, acrylic polymer paint with glitter and uv-cured ink on canvas, 80 x 60 x 2 in (203.2 x 152.4 x 5.1 cm)