Artist: Tenant of Culture

Exhibition title: Eclogues (an apology for actors)

Venue: Nicoletti Contemporary, London, UK

Date: September 30 – December 14, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Nicoletti Contemporary, London

The work of Tenant of Culture (the artistic practice of Hendrickje Schimmel, 1990, NL) investigates the ethics and politics inscribed in garments and fashion styles. Departing from aesthetic trends that she locates in aspirational lifestyle magazines, social media or on the streets, Tenant of Culture analytically deconstructs manufactured garments to examine the ways in which conceptual and ideological frameworks materialise in methods of production, circulation and marketing of clothes. In her practice, the processes of deconstruction and reconfiguration of apparels into sculptural assemblages operate as means to conjure up the dialectical nature of fashion, whose primary function is to avoid alienation from society through resemblance, yet mobilising this function through what Georg Simmel identified in Fashion (1905) as the paradoxical logic of ‘standing out while fitting in’. At work within this logic is a codification of visual languages which reflects dynamics of power, domination and assertion of social status via a constant re/devaluation of goods.

Eclogues (an apology for actors) – Tenant of Culture’s newly commissioned exhibition at Nicoletti Contemporary, London – examines the underlying power structures hiding behind the romanticisation of nature, rural virtues and manual labour in current lifestyle aesthetic trends. Comprised of a new series of sculptures incorporating recycled garments and accessories, the exhibition specifically analyses how values of authenticity, integrity and rusticity are presently being branded as status symbol and visionary politics within an ecologically-concerned era. The term eclogues – which refers to the antic literary genre of pastoral poetry otherwise known as Bucolics – is therefore used to designate a tendency towards what the artist calls a ‘regression aesthetics’, conspicuous in the popularity of organic looking garments and recent return of rustic materials, bonnet caps, reed baskets and aprons in lifestyle magazines and high-street vitrines. Under the varnish of this apparently innocent aesthetic, however, lurks a ‘pastoral nostalgia’ which cyclically re-emerges across history in moments of crisis. Reflecting the inherent tension between ideas of progress and environmental concerns, this pastoral nostalgia often takes the form of alter-progressist ideologies based on the mystification of a past that never was; one inspired by medieval, pre-capitalist times in which skilled artisans and cheerful peasants were peacefully living amid fertile fields and untouched nature. If, the exhibition asks, such pastoral desires could a priori be seen as stemming from the progressive development of an ecological consciousness, what are the active sociopolitical forces rooted in rural aspirations and hypothetical ‘return to nature’?

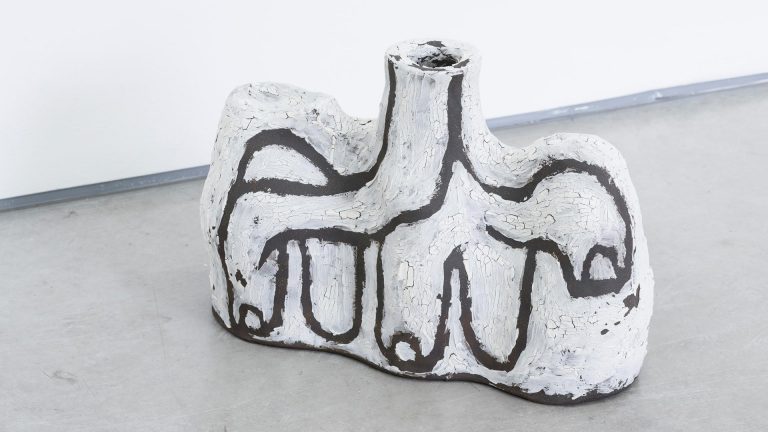

Tenant of Culture is addressing this question by focusing her attention on the allegorical figure of the ‘milkmaid’, which recently re-emerged in fast fashion chain stores such as Boohoo and Topshop selling £5 versions of the ‘milkmaid’ top; a virgin white, frilly, off-shoulder cotton garment which, as the artist ob-serves, ‘conspicuously employs this visual identifier to communicate female innocence, fertility and (re)productivity’. Indeed, the milkmaid is an historically loaded figure, which has been used to convey values of rural labour and female virtuousness, operating in art and literature as the epitome of the fecund, nurturing body. Through a series of enamelled busts that she dresses with headpieces referencing the classic milkmaid bonnet cap, Tenant of Culture analyses the sociopolitical function that the milkmaid has fulfilled across history and questions the significance of its reappearance in the current context.

Adorned with deconstructed wigs and hairpieces made by the hair and wig artist Fraziska Presche, the busts form a group of characters which enact the fashionable milkmaid within a stripped-down theatrical display inspired by the retail environment. In relation to the milkmaid allegory, this method of display operates as a contemporary translation of the early modern ‘pleasure dairy’ – the marble-carved pastoral architecture in which aristocratic women played the milkmaid character (the most famous example being Marie-An-toinette’s Hameau de la Reine in Versailles). Already indicative, during the eighteenth century, of an utterly idealised vision of rural labour by the urban elite, the milkmaid narrative is here performed within the clinical and sterilised environment of the retail store (and the art gallery) to pinpoint the appropriation of manual labour and workwear aesthetic by the fashion industry. The range of materials used in the textile assemblages – typical ‘city’ garments including white t-shirts, suits and industrial fabric in which the artist sometimes inlaid organic components such as flowers and straws – also suggests this tension between urban and rural life, as well as the unbalanced relationship between humans and their environment. Here, however, the intricate construction of the garments, in which assemblages of synthetic materials fake a ‘natural’ appearance while organic materials are used to create abstract ornamental patterns, problematises the habitual opposition between the naturally given and the industrially produced at work within pastoral ideals. Tenant of Culture’s milkmaids, on the contrary, point to the limitation of an ecological thinking that would obliterate the economic, social and territorial problematic embedded in the ecological question; by being presented as both symptoms and actors of the unequal relations of production, class and territories embedded in pastoral narratives, they expose the hypocritical dimension of discourses calling for a ‘return to nature’ – often articulated by the classes detaining the means of production.

Indeed, in Eclogues (an apology for actors), the endorsement of rural virtues and ancestral labour, of which the milkmaid phenomenon is but one example, is less seen as the sign of a sentimental connection to nature than as participating in the normalisation of conservative discourses based on the return to traditions. In this sense, Tenant of Culture does not only use the theatrical display of the milkmaids as a demonstration of the heteronormative structures inducing women to perform stereotypes; the milkmaid attire acts as a symptom of the active dissemination and passive acceptation of the neo-reactionary ideas masked beneath pastoral desires. Stripped-down of any identifiable facial feature, the characters playing in Tenant of Culture’s eclogue are brought back to their condition of typified bodies as busts or mannequins; no longer the conscious individuals acting out in a pastoral play or poem, they are presented as the anonymous actors playing the ever-renewed script of consumerist trends.

Text by Camille Houzé