Artist: Tanea Hynes

Exhibition title: Locally Hated

Venue: KIN, Brussels, Belgium

Date: June 18 – July 26, 2024

Photography: installation views: ©Josh Jensen and individual views: ©Fabrice Schneider, all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and KIN, Brussels

Town of Uneven Love (But All Love is Uneven)

Towns are illusions that things hang together naturally. But the town, or its illusions, hold themselves around matter of all sorts: a body of water, mountains, big holes etc. Rent a car from Montreal YUL Airport with Labrador City as your destination in mind: you will traverse 1240 kilometres over eighteen hours. The route takes you over a small body of water on the Tadaoussac-Québec ferry and an inch over the border between the province of Québec and Labrador you will have gained an hour on your watch.

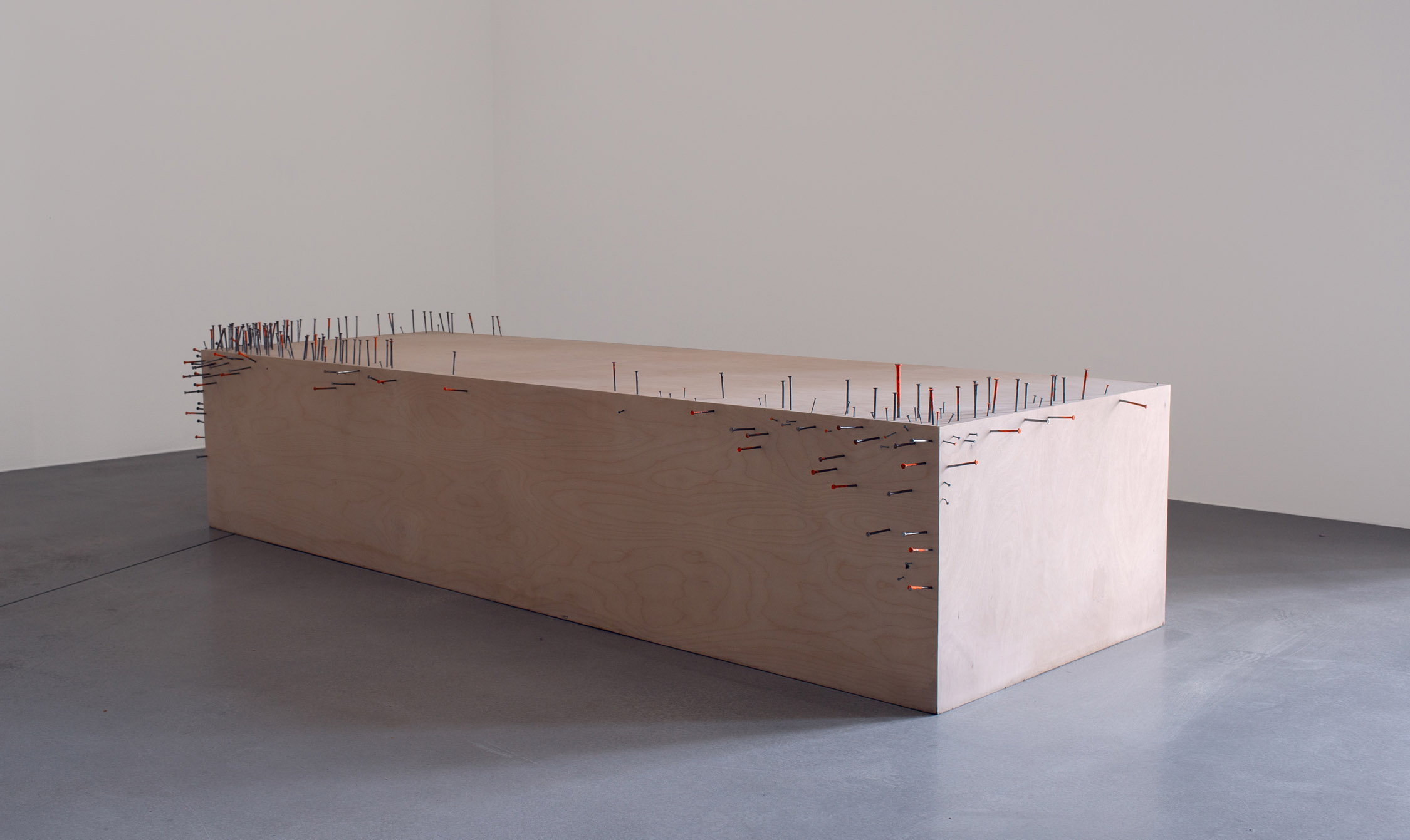

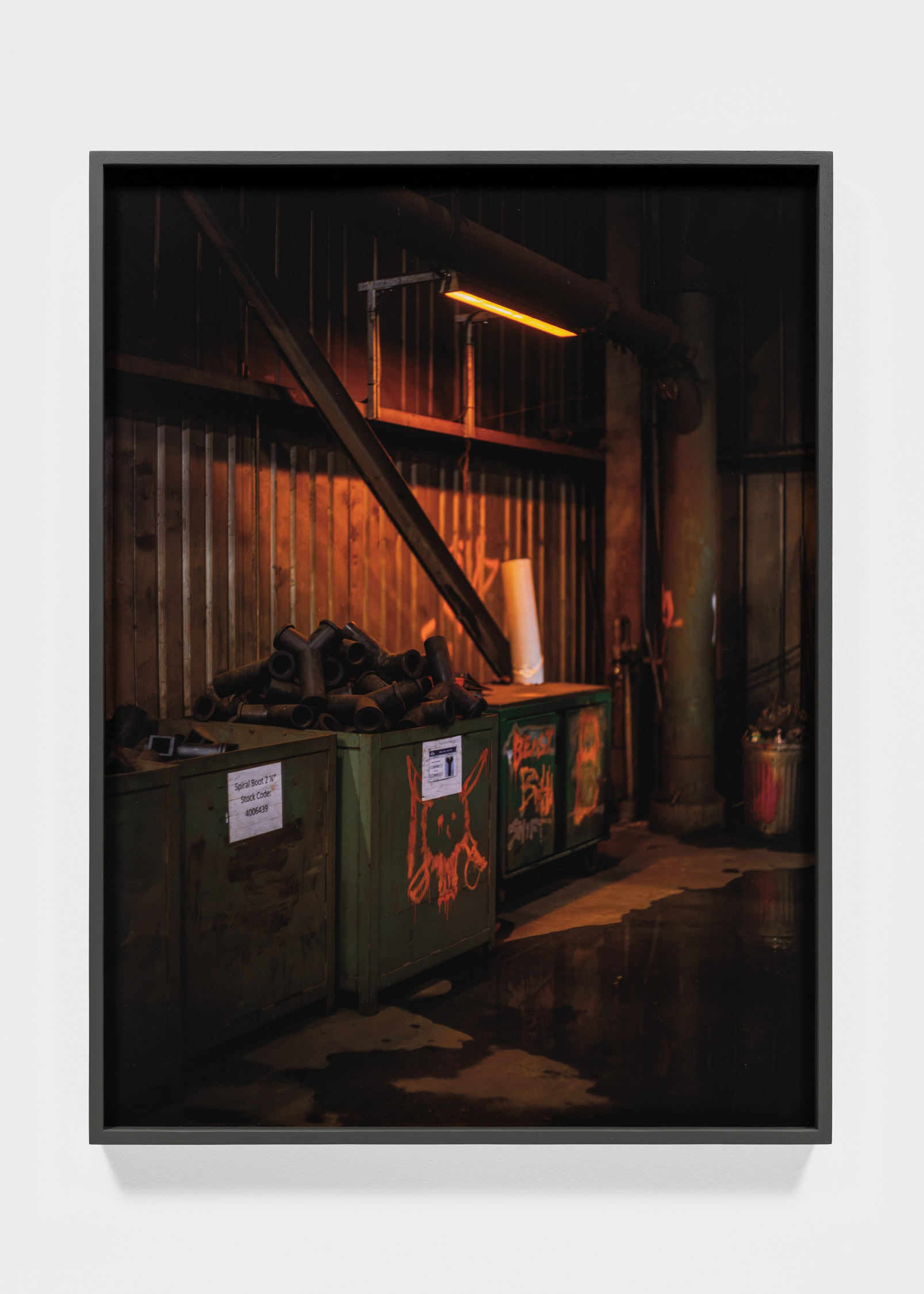

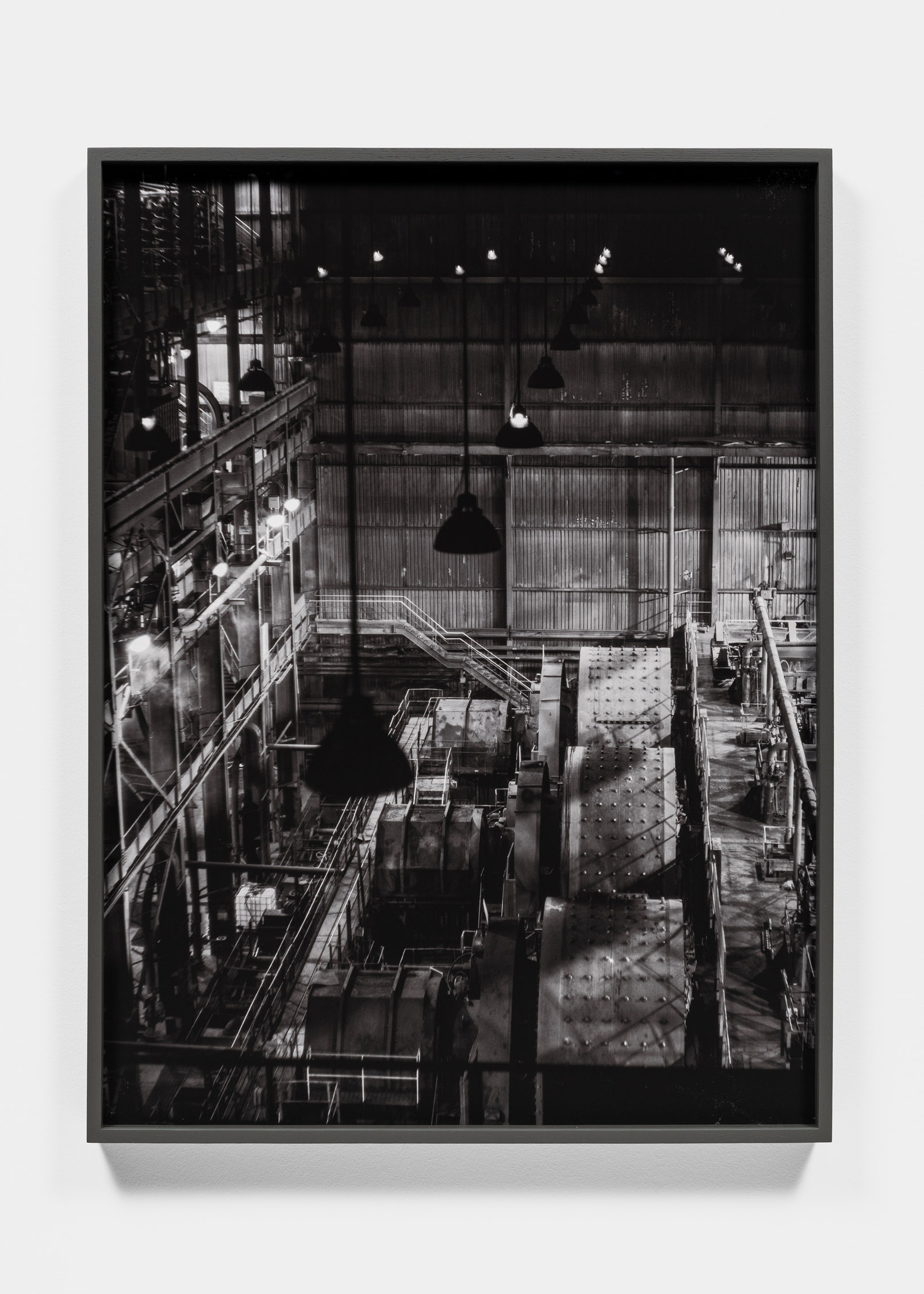

Labrador City is a town dedicated to the extraction of iron ore. This procedure remains the chief driver of its economic success since the town was built in the 1960s. Deposits of iron ore were first discovered by the Iron Ore Company of Canada in the area around 1892 and it was then that the idea of the town began.

Since then, the town has seen the arrival and departure of workers, managers, and spouses of those penchant on making a buck from major scale hole-making and rock removal. In its raw form, iron ore is a substance concentrated in rocks or minerals found beneath the earth’s surface. Then it is extracted, crushed, screened, crushed again, ground up. In its refined form, it is a perfectly soluble end-product. All that remains is for the uneconomic fraction of iron ore to be pumped back towards the landscape.

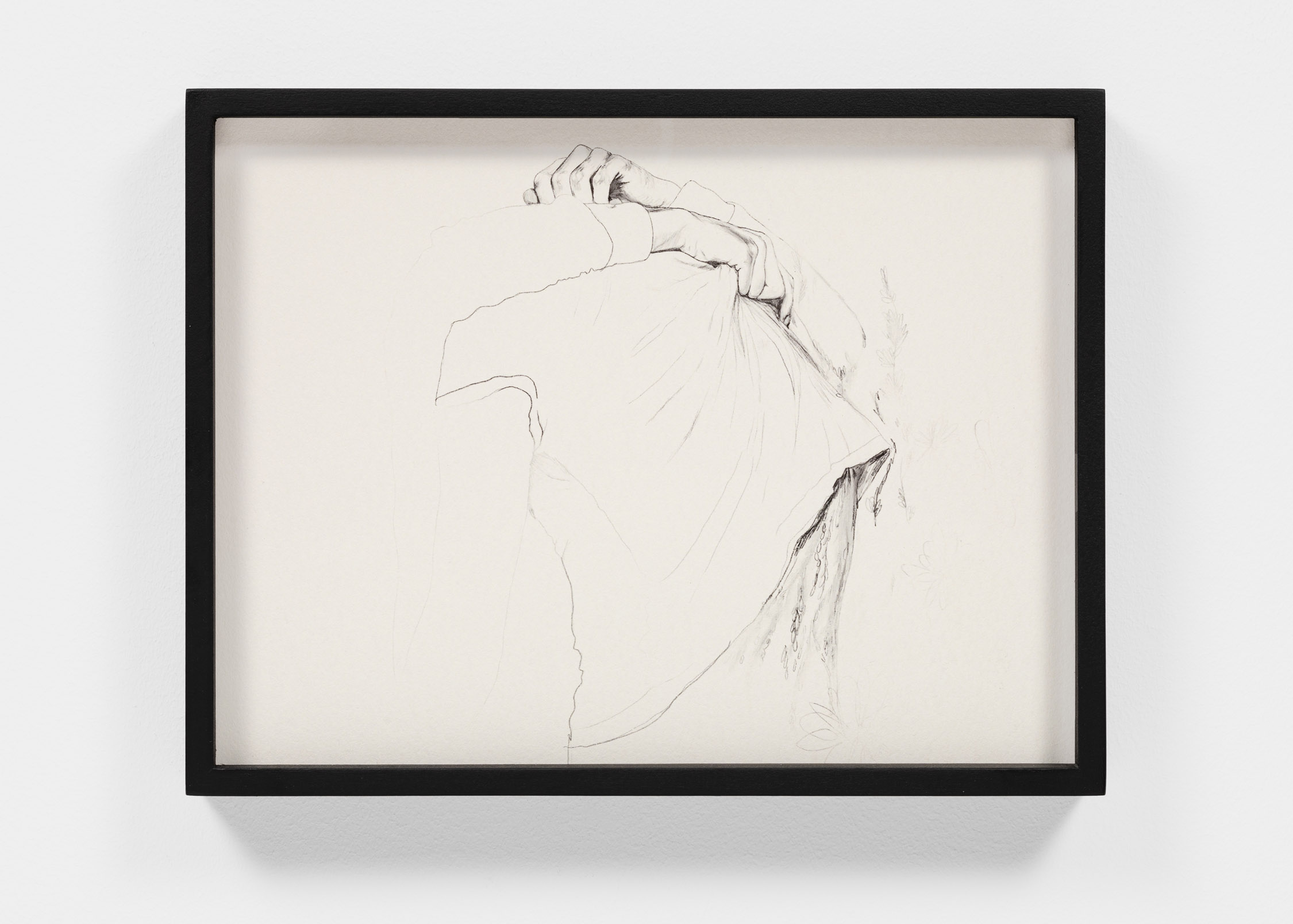

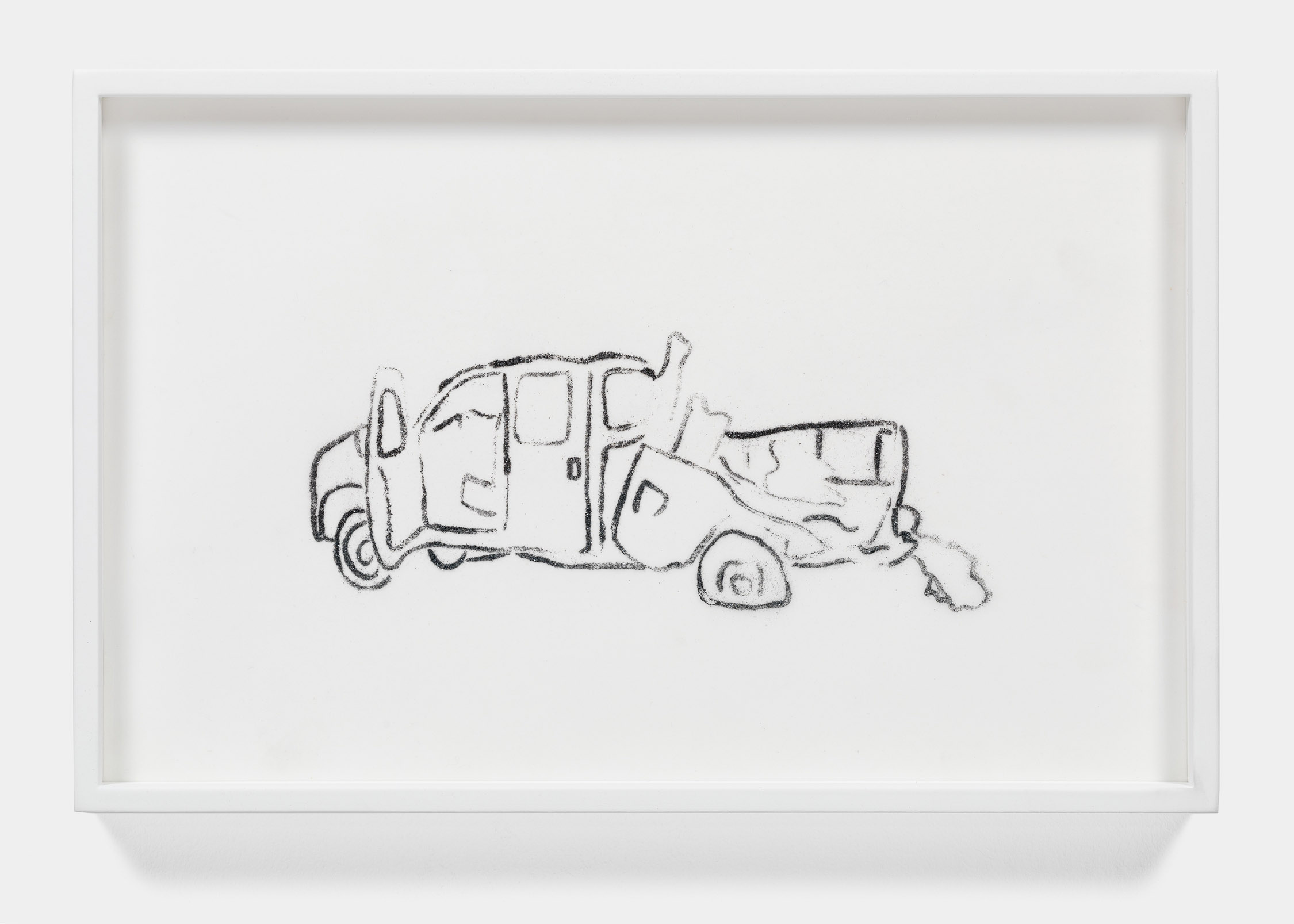

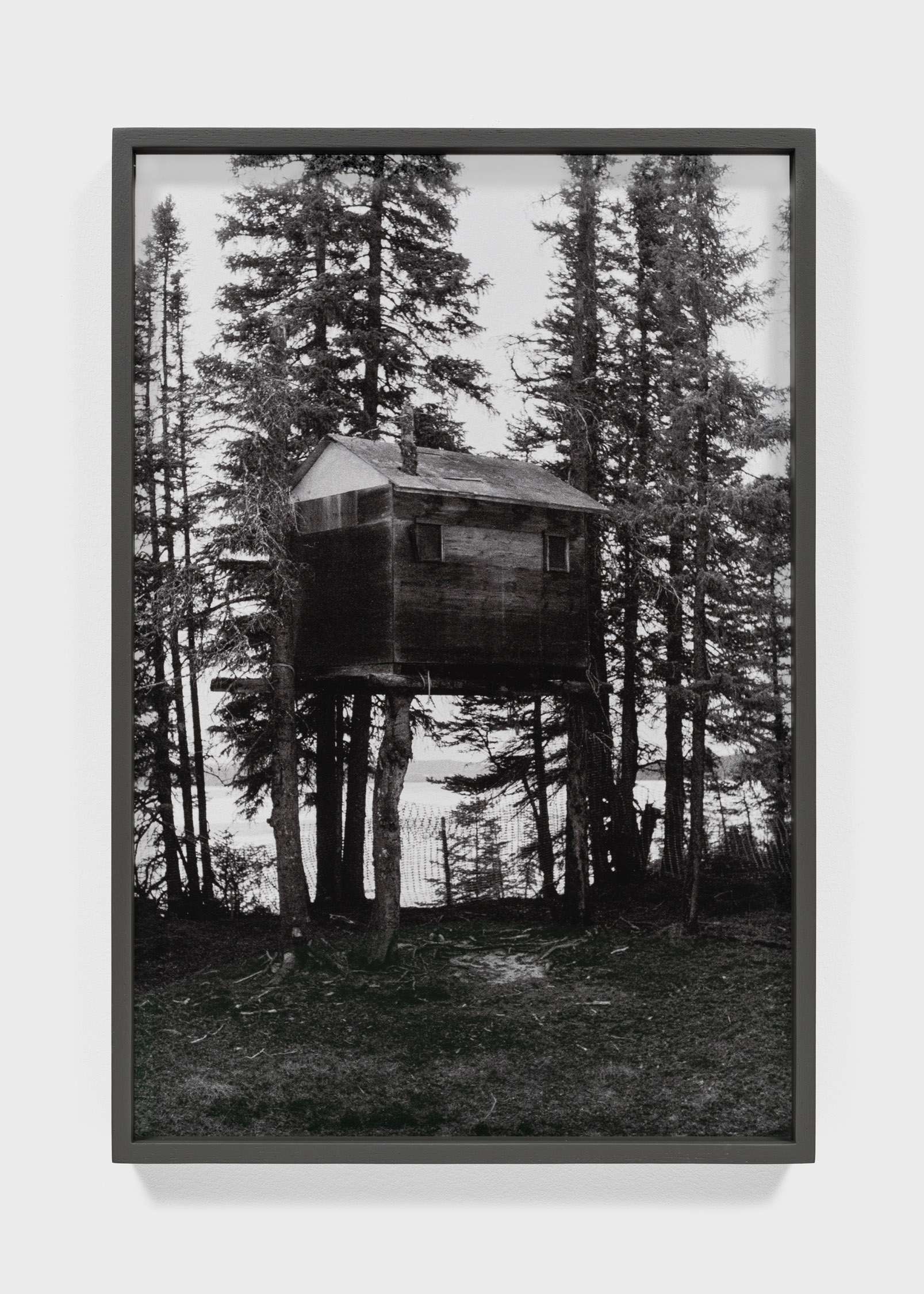

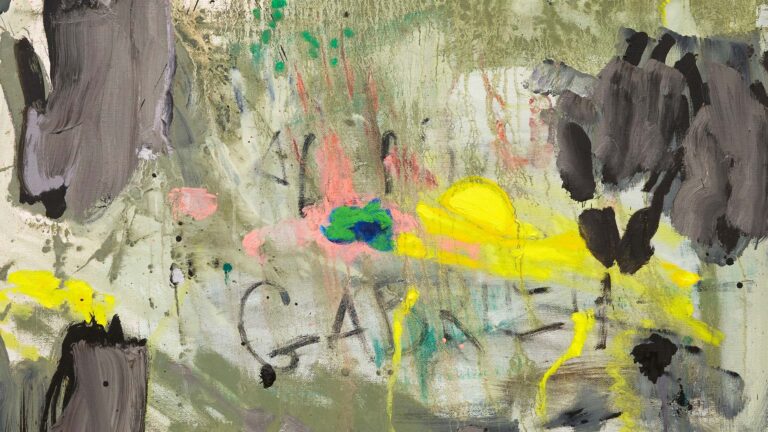

A week before we open the show, Hynes tells me that there is enough iron in the human body alone to make a fairly large nail. The artist was born and raised in Labrador City by a family whose subsistence is a direct effect of the mine. Hynes too was an employee for a time. The artist’s work takes an oblique look at the mining town arm in arm with its co-curriculars. The scenes vary: a man standing beside his Ford 150, a drawing of a strike shack, a crushed truck drawn with iron ore concentrate, two swimmers and a pond framed by the mine in the distance. In each, Hynes underlines how an unequal combination of economy, land and life prove to be inseparable yet as foundational as a page of the creation. Faced with a scale of production that outweighs human lives by the thousands of tonnes, Hynes’ body of work amalgamates photography, drawing and sculptural forms as agents or pillars of documentary: a quality felt to be sober but subjective.

The most prolific antecedent to Hynes’ approach is the history surrounding documentary throughout her home province. Between 1950 and 1970, documentary filmmaking became the most successful apparatus for socio-political change that the region had ever seen. It brought the faraway problems facing towns and small communities straight to the doorstep of the federal government in Ottawa who were forced to provide answers and solutions to those affected by the impoverished economic conditions that were the result of large-scale natural resource guzzling.

While Hynes’ work approaches these possibilities with the grammar of an optimism that spoils quickly, there will be no revolution from major-scale resource extraction. The scale is far too large. The final summer Hynes was employed at the mine, the global conglomerate of Rio Tinto (58.7%), Mitsubishi (26.2%) and the Labrador Iron Ore Royalty Income Corporation (15.1%) opened a new open-pit mine that would ensure the region at least 50 more years in business. For Hynes, the presence of the paradox seems to be enough. The bones of extraction are odious and unrelenting but they are necessary to the ongoing and typical runnings of everyday life.

In the end, resource extraction isn’t just the story of one town, or even one commodity. It is the story of many towns, across many commodities and their separate or joined transcontinental voyage for increased production elsewhere. It is this web of entangled relations between land ownership, labour and life that connect this body of work to other realities that rely on labour-intensive extraction for continued survival.

-Micaela Dixon