The Registry of Promise is a series of exhibitions that reflect on our increasingly fraught relationship with what the future may or may not hold in store for us. These exhibitions engage with and play upon various readings of promise as simultaneously anticipating a future and its fulfillment or lack thereof, as well as a kind of inevitability, either positive or negative. Such polyvalence assumes a particular poignancy in the current historical moment. Given that the technological and scientific notions of progress inaugurated by the Enlightenment no longer have the same purchase they once did, we have long since abandoned the linear vision of the future the Enlightenment once betokened. Meanwhile, what is coming to substitute our former conception would hardly seem to be a substitute at all: the looming specter of global ecological catastrophe. From the anthropocentric promise of modernity, it would seem, we have turned to a negative faith in the post-human. And yet the future is not necessarily a closed book. Far from fatalistic, The Registry of Promise takes into consideration these varying modalities of the future while trying to conceive of possible others. In doing so, it seeks to valorize the potential polyvalence and mutability at the heart of the word promise.

Taking place over the course of approximately one year, The Registry of Promise consists of four autonomous, interrelated exhibitions, which can be read as individual chapters in a book. It was inaugurated by The Promise of Melancholy and Ecology at the Fondazione Giuliani, Rome, followed by The Promise of Multiple Temporalities at Parc Saint Léger, Centre d’art contemporain, Pougues-Les-Eaux and The Promise of Moving Things at Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, and will conclude with The Promise of Literature, Soothsaying and Speaking in Tongues at De Kabinetten van De Vleeshal, Middelburg.

The Registry of Promise: The Promise of Literature, Soothsaying and Speaking in Tongues

Artists: Becky Beasley, Michael Dean, Jean-Luc Moulène, Matt Mullican, Reto Pulfer, Lucy Skaer, Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli

Venue: De Kabinetten van De Vleeshal, Middelburg, The Netherlands

Date: January 25 – March 29, 2015

Photography: Leo van Kampen, courtesy of SBKM/De Vleeshal

The fourth and final part of The Registry of Promise: The Promise of Literature, Soothsaying and Speaking in Tongues, addresses language, modes of writing and the book. Stretched to its breaking point while being at once materialized and dissolved into a certain opacity, language assumes a plastic quality in this exhibition—as if it were something that could be grabbed onto and held, and yet remained entirely beyond one’s grasp. What is more, in this exhibition language has been made to shed its practical capacity of communication, entering into a much more marginal space of purpose, while nevertheless seeking to foster a productive, if at times, sinister reverie.

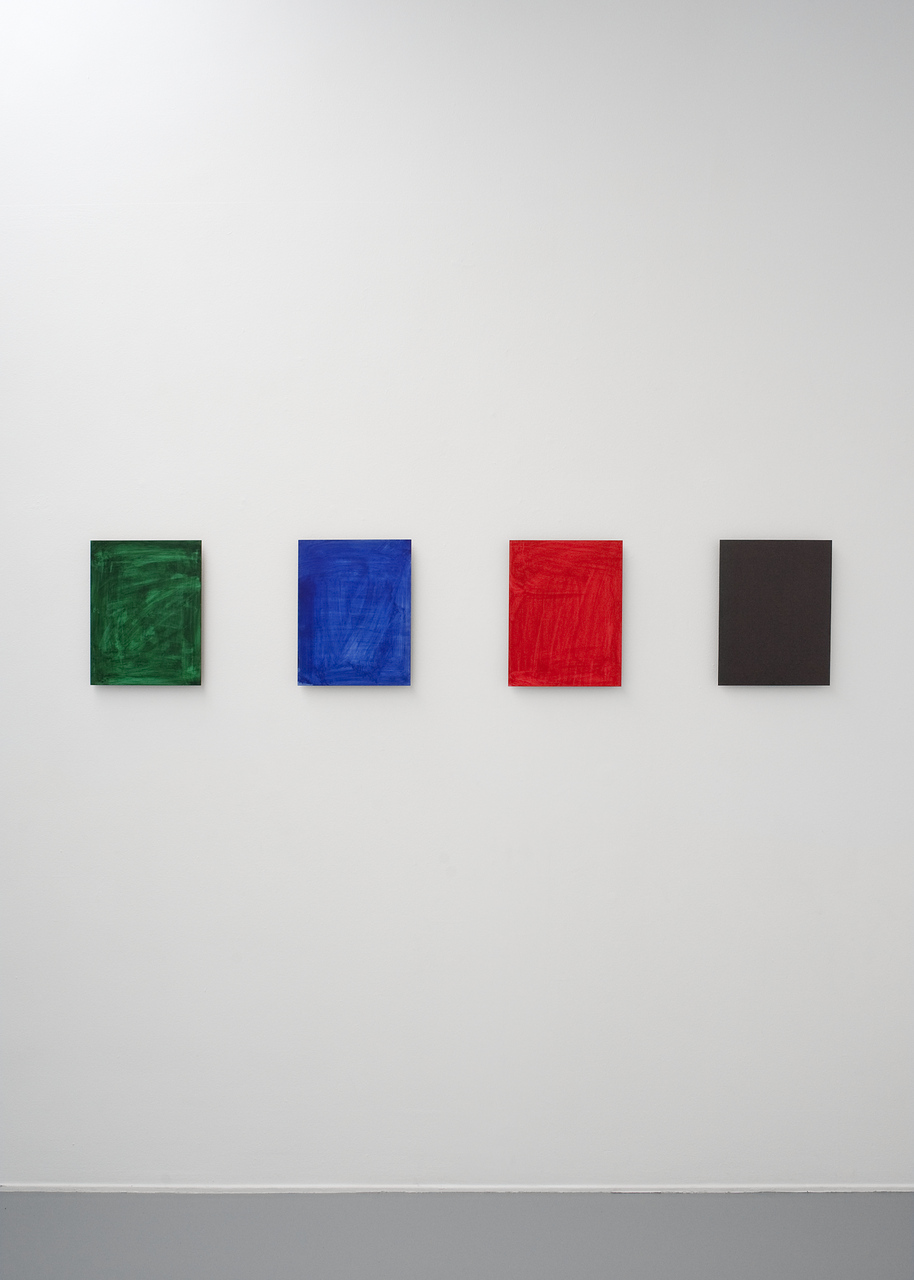

All the artists included in this exhibition have a close relationship to language, but one which varies both formally and referentially. Becky Beasley and Michael Dean possess a distinctly literary approach, as in Beasley’s paper back-sized sculpture A Storage Space (After Faulkner), 2008. Fashioned out of Black American Walnut and black glass, this sculpture, whose dimensions is the same as two, identical Penguin editions of William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, borrows the aesthetic vocabulary of minimalism, underlining its historical antagonism to narrative and effectively funereal character through the definitive closure of the book—a closure that nevertheless does not shut down narrative possibility, but rather opens it up through its very absence. This more pointed literary work is complemented by the suspended rotating sculpture, Bearings, 2014. This three-meter-long, brass cast is made from nine twigs collected by the artist’s father from windfall after the St. Jude storm. Assembled as such, they could be read as a syntactical construction evocative of a divining rod. Michael Dean’s hnnnhhnnn-hnnnhnnnnh (Analogue Series), 2014, consists of a dictionary drenched in red ink and left out in the sun to dry. Twisted and gnarled, it resembles a large, red tongue, itself beleaguered and ultimately disfigured by language. Other artists, such as Jean-Luc Moulène and Lucy Skaer sublimate language into form, transposing it into something that at once transcends and remains immured in a decidedly unintelligible signification. Moulène’s Echantillon/Monochome, New York, March 2010, for instance, comprises four panels, which have been uniformed colored with Bic felt markers. Readable as so many palimpsests laboriously transformed into monochromes, these panels speak to a glut and total saturation of word stuffs. Lucy Skaer’s sculptural installation Untitled (Le Siege), 2009, consists of a table whose surface has been carved into an 0 and which she uses to draw prints from. Language’s communicative function is subordinated to a seemingly counterintuitive image-making process. The work of Matt Mullican, Reto Pulfer and Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli address language as something that exists between divination, world-making and speaking in tongues. While Matt Mullican is known for entering trance states to draw and write, elaborating systems as he proceeds, as exemplified in the complex drawing Chart, 2003, presented here, the work of Reto Pulfer creates sculptures and installations based on his own private language systems. The work Hermetisch, 2006, which involves cards, language and sticks, is activated by a performance in which chance and language determine the overall structure of the final result, which is evocative of a kind of soothsaying ritual. Finally Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli’s installation Reperti per il prossimo milione di anni (2007–09) is the byproduct of an attempt to create a myth and ritual in the 21st century, whose primary audience is located in the future. Composed of everything from performance, photography, drawing, video, sculpture and installation, the final product consists of a meticulously and methodically constructed archive, which, for all its will to fashion a future myth, is ultimately inscrutable.

Michael Dean, hnnnhhnnn-hnnnhnnnnh (Analogue Series), 2014

Becky Beasley, A Storage Space, 2006

Lucy Skaer, Untitled (Le Siege), 2009

Jean-Luc Moulène, Echantillon/Monochrome New York, mars 2010, 2010

Reto Pulfer, Hermetisch (Pencils vs Papers), 2006

Matt Mullican, Chart, 2003

Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli, Reperti per il prossimo milione di anni (Archivio), 2007/2009/2012

Carlo Gabriele Tribbioli, Reperti per il prossimo milione di anni (Archivio), 2007/2009/2012

The Registry of Promise: The Promise of Moving Things

Artists: Nina Canell, Alexander Gutke, Antoine Nessi, Mandla Reuter, Hans Schabus, Michael E. Smith

Venue: Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, France

Date: September 12–December 21, 2014

Photography: Courtesy of Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry

The third part of The Registry of Promise, The Promise of Moving Things deals with the so-called life of objects in our current pre-post-apocalyptic paradigm. Influenced in equal measure by animism, the much-discussed philosophical movement Object Oriented Ontology, the surrealism of Alberto Giacometti’s early masterpiece The Palace at 4 am (1932) and even the theoretical reflections of the Nouveau Roman novelist, theorist and editor Alain Robbe-Grillet (an OOOer, so to speak, well avant la lettre), The Promise of Moving Things seeks to address just that—the very idea that there exists some promise within objects in a world in which humans no longer roam the earth. Neither a critical rejection nor an endorsement of these ideas, the exhibition embraces the ambiguity at the very heart of the word promise. It questions to what extent this negative faith in the cultural and animistic legacy of objects is a genuine rupture with the anthropocentric tradition of humanism and to what extent it is merely a perpetuation of it.

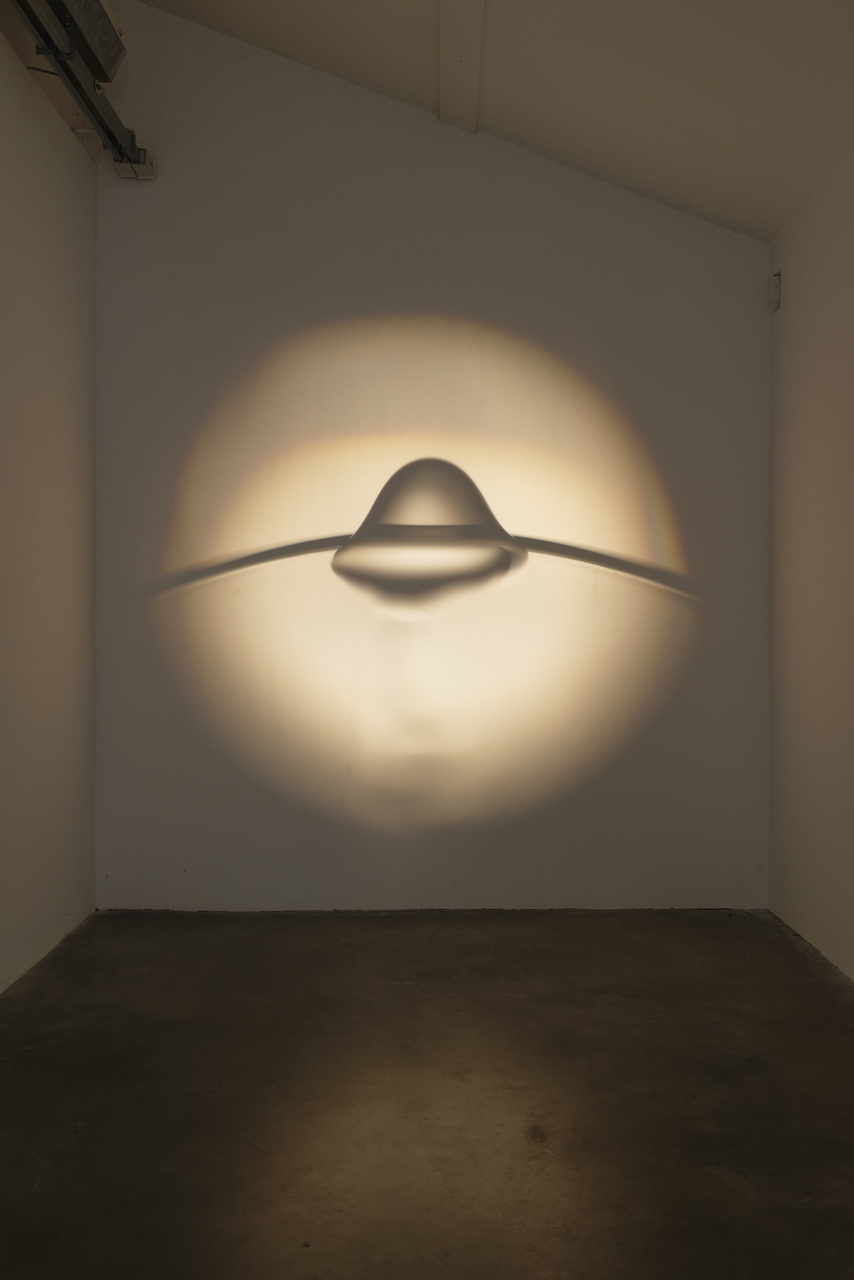

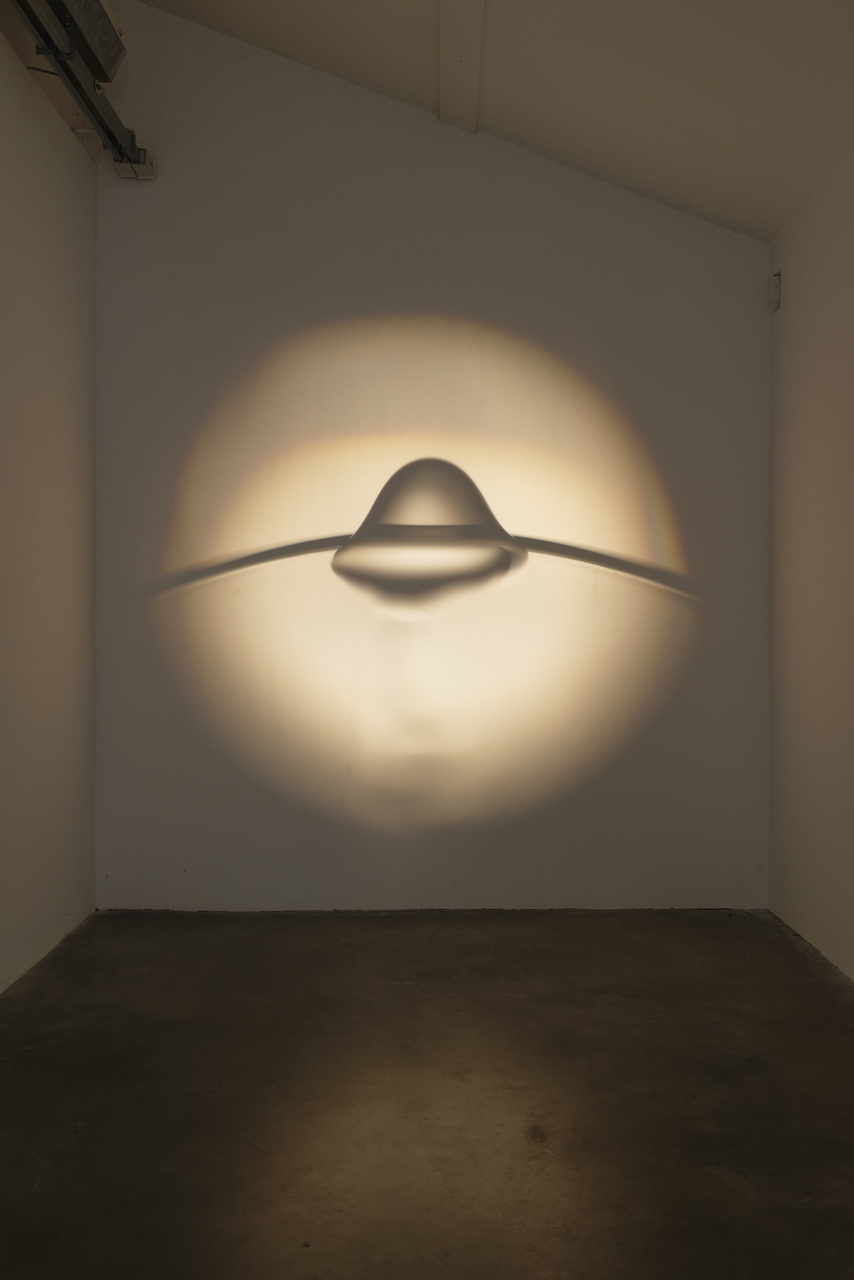

Thus does the exhibition consist of works that features objects or processes which seem to possess some form of human subjectivity. For instance, the Austrian, Vienna-based artist Hans Schabus’s sprawling sculptural installation Konstruktion des Himmels (1994) could merely be a random collection of variously seized wax balls and an elaborate light fixture or the most human forms of celestial organization: a constellation (which it is: a recreation of Apparatus Sculptoris [Sculptor’s Studio], identified and named in the 18th century by Louis de Lacaille). Almost, but not entirely by association, German, Berlin-based Mandla Reuter’s sculpture installation The Agreement (Vienna) 2011, which has been paired with Schabus’s work and is comprised of an armoire hanging from the ceiling, assumes a quasi-, supernatural and animistic quality. The transference of so-called human subjectivity is unmistakable in Swedish, Malmö-based Alexander Gutke’s work Autoscope (2012). This 16mm film installation portrays the trajectory of a piece of film passing through the interior of a projector, exiting into a snowy, tree-dotted landscape, ascending upward into the sky before plunging back down to earth and looping back into the projector, and repeating the process, all as if in an allegory of reincarnation. The American, New Hampshire-based artist Michael E. Smith’s slight sculptural interventions, which often consist of recycled textiles, materials from the automotive industry, animal parts, and a variety of toxic plastics, are known to possess qualities hauntingly evocative of the human body, as if the spirit of one had entered the other. Drawing his formal vocabulary from machines and tools, French, Dijon-based artist Antoine Nessi creates sculpture, which can perhaps be best described as post-industrial, in which the inanimate seems to take on an organic quality, assuming a life of their own. Finally, the practice of the Swedish, Berlin-based artist Nina Canell is no stranger to the kinetic and to a certain, if specious, sense of animism. Something of a case in point, Treetops, Hillsides & Ditches (2011) is a multi-part sculpture comprised of four shafts of wood over the top of which a clump of Iranian pistachio gum has been spread and which slowly crawls down the sides of the wood, enveloping it, like living a skin.

Thus is the reception of each work complicated and vexed through issues of subjectivity, projection, necessity, and desire. Now to what extent the works are complicit in that reception both varies and is debatable. Whatever the case may be, it is virtually impossible to say, but this does not necessarily mean that it is impossible to conceive of a world without humanism, as argued by Robbe-Grillet, at its center.

Mandla Reuter, The Agreement, Vienna, 2011

Mandla Reuter, The Agreement, Vienna, 2011

Antoine Nessi, Unknown Organs, 2014

Antoine Nessi, Unknown Organs, 2014

Nina Canell, Treetops, Hillsides and Ditches, 2011

Nina Canell, Treetops, Hillsides and Ditches, 2011

Nina Canell, Present Tense, 2014

Nina Canell, Present Tense, 2014

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2014

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2014

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2014

Hans Schabus, Konstruktion des Himmels, 1994

Hans Schabus, Konstruktion des Himmels, 1994

Alexander Gutke, Auto-scope, 2012

Alexander Gutke, Auto-scope, 2012

Alexander Gutke, Auto-scope, 2012 (Still from film)

Alexander Gutke, Auto-scope, 2012 (Still from film)

The Registry of Promise: The Promise of Multiple Temporalities

Artists: Patrick Bernatchez, Juliette Blightman, Rosalind Nashashibi, Francisco Tropa, Andy Warhol, Anicka Yi

Venue: Parc Saint Léger Centre d’art contemporain, Pougues-les-Eaux, France

Date: June 14–September 14, 2014

Photography: Courtesy of Parc Saint Léger, Centre d’art contemporain

Part two, The Promise of Multiple Temporalities, responds to the collapse of faith in progress, and the singularly conception of linear time that underpinned it with another conception of time, which is multifarious, contradictory, and nevertheless co-existent. Here time spiders out into a variety of directions, alternatively expanding, coming to a grinding halt, circling back upon itself, or transforming into water. A single revolution of Canadian artist Patrick Bernatchez’s Black Watch (2011), specially commissioned to a Swiss watch maker, requires not the usual 24 hours to go full circle, but a thousand years, and in doing so, dwarfs human cycles of time to virtually nothing. Where this work uses the watch to extend time virtually beyond human comprehension, Portuguese, Lisbon-based artist Francisco Tropa’s Lantern (2012) goes back, so to speak, to the beginning of time. Part of his ongoing investigation of antique time-telling devices, Lantern, is a recreation of a clepsydra—an ancient device for measuring time by the regulated flow of water through a small aperture—which is then projected on the wall, like a magic lantern. English, Berlin-based artist Juliette Blightman’s This World is not My Home (2010) telescopes time onto two periods of the afternoon: 3pm, which could be considered the dead time of the day; as well as 5pm, which is traditionally quitting time. The work is comprised of a chair on a rug with a fire grate placed in front of an open window. Every day at 3pm, a single log is placed on the grate and lit, and then every day at 5 o’clock the song “This World is not My Home” by Jim Reeves plays. Rosalind Nashashibi’s The Prisoner (2008) could be said to compress the loop embedded in Blightman’s work. This 16mm two-projector film installation, which feeds the same film through both projectors at naturally non-synchronized screenings, depicts a woman climbing a set of stairs over and over again, as if trapped in the same infernal instant. Andy Warhol’s Sleep (1963), which consists of an image of John Giorno sleeping for five hours and twenty minutes is a classic literalization of cinematic time as time. American, New York-based Anicka Yi’s work Tenzingbaharakginaeditscottronnienikolalosangsandrafabiansamuel

aninahannahelaine (2013) embodies, among other things, the sense of memento mori that inevitably courses through the entire exhibition. For this sculptural installation, Yi deep-fried flowers in tempura batter and then placed them in a Donald Judd-like series of card board boxes full of resin. What is more, given the organic nature of this work, it is necessarily dialectical, in so far as, it is unstable and it will evolve over time.

Anicka Yi, Some End of Things, 2013

Anicka Yi, Some End of Things, 2013

Patrick Bernatchez, BW, 2011

Francisco Tropa, Lantern (drop), 2012

Rosalind Nashashibi, The Prisoner, 2008

Rosalind Nashashibi, The Prisoner, 2008

Andy Warhol, Sleep, 1963

Andy Warhol, Sleep, 1963

Juliette Blightman, This World is not my Home, 2010

The Registry of Promise: The Promise of Melancholy and Ecology

Artists: Peter Buggenhout, Jochen Lempert, Marlie Mul, Jean-Marie Perdrix

Venue: Fondazione Giuliani, Rome, Italy

Date: May 9 – July 18, 2014

Photography: Giorgio Benni, courtesy of Fondazione Giuliani, Rome

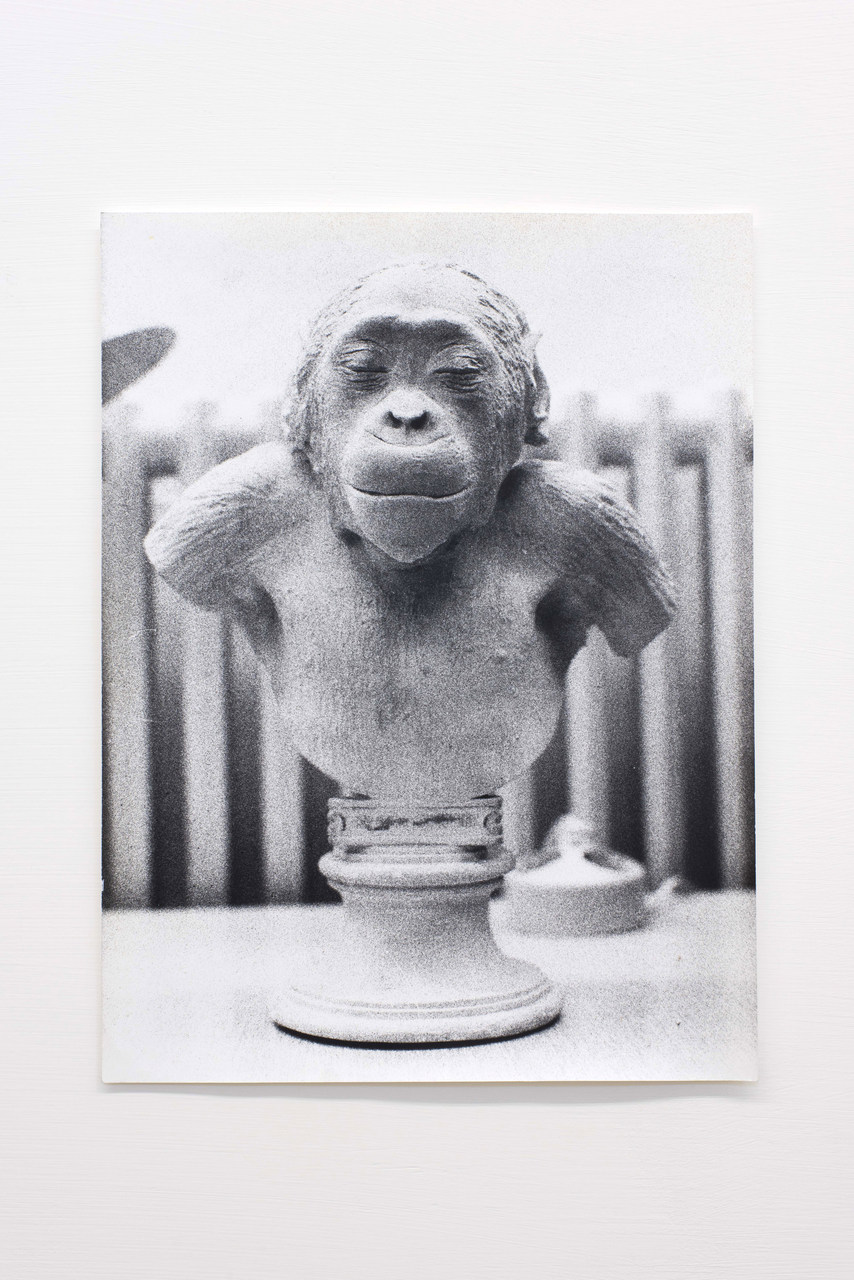

Part one, The Promise of Melancholy and Ecology, addresses our increasingly forlorn and conflicted relationship with nature. Like so many Freudian melancholics, we are, it seems, unable to properly mourn the loss of something we can only imperfectly and incompletely grasp—nature, or our conception of it—because we can no longer separate it from our own egos. Thus this exhibition explores our perception of nature as something remote, largely of the domain of the unrecoverable past, and which can only be represented through extinction, as in the photos of Jochen Lempert of the Alca Impennis, or the Great Auk, which went extinct in the middle of the 19th century. Over the course of the past twenty years, Lempert has photographed 35 of the 78 extent examples, which can be found in natural history museums all over the world. The harrowing bronze and carbon sculptures of truncated animals by the French artist Jean-Marie Perdrix, which are made with the lost wax technique, speak to a similarly bygone intimacy with nature, but one whose infernal indexicality cannot but directly evoke Pompeii. The Belgian artist Peter Buggenhout’s tenebrous detrital assemblages tend toward a revised conception of the so-called natural by investing industrial materials with a quasi-organic quality. Finally, Dutch artist Marie Mul’s dark resin puddles, occasionally inflected with cigarette butts and plastic bags, assume a disturbing cogency in this context, as if they were the only plausible fluids available to our increasingly desolate conception of nature. And yet for all its apparent gloom, the work in this exhibition nevertheless collectively gestures toward the possibility that our perception of what it seeks to preserve, as opposed to mourn, might be less flexible than nature itself.

Jochen Lempert, The Skins of Alca impennis, 1993 – 2014

Jochen Lempert, The Skins of Alca impennis, 1993 – 2014

Jochen Lempert, Untitled, 2005

Peter Buggenhout, Gorgo #29, 2013

Marlie Mul, Puddle (Black Clump), 2014

Marlie Mul, Puddle (Black Clump), 2014

Jean-Marie Perdrix, Cheval, bronze à la chair perdue 3, 2013

Jean-Marie Perdrix, Cheval, bronze à la chair perdue 3, 2013

Jochen Lempert, Untitled (from: Symmetry and the Architecture of the Body), 1997

Jochen Lempert, Untitled (from: Symmetry and the Architecture of the Body), 1997

Afterword by curator Chris Sharp

This sprawling, quasi pan-European yet compact series of exhibitions, which spanned from May 9, 2014 to March 29, 2015, originated in an invitation to compete for the curatorship of the 8th Berlin Biennial. Pre-selected to jockey for the stewardship of this prestigious exhibition, I in turn invited the Italian, Milan-based curator Simone Menegoi to compete with me. Simone Menegoi and I conceived a proposal revolving around the collapse of the future and submitted it. When we found out that we would not be advancing to the next stage of the process, I discussed the proposal with Claire Le Restif, the director of Le Credac: Centre d’art d’Ivry, whom I had already been engaged with in a discussion about potentially curating an exhibition at her institution and who quickly became interested. It just so happened that at about that same time, the French cultural scene was planning a year-long exchange with Italy, and Claire saw this exchange as an opportunity to both host the exhibition and create partnerships among like-minded and similarly scaled institutions. Thanks largely to her efforts and enthusiasm, three other partners came on board: La Fondazione Giuliani in Rome, Le Parc St. Léger in Pogues-les-Eaux, France, and De Vleeshal in Middelburg, Holland. Unfortunately, however, at this point Simone Menegoi, who had become overwhelmed by other commitments, decided to withdraw from the project, so I pressed on on my own. Retaining the core idea of our concept regarding the future, I radically revamped the overall project, changing the title, language, and form into something of a much more literary order. Where Simone and I were originally influenced by the work of French anthropologist Marc Augé, my transformation of the project was indebted to the American novelist Ben Marcus, and in particular, his novel The Flame Alphabet (2012). Exactly how Marcus influenced the overall project is not so much hard to say, as it is difficult to describe. His influence could be traced in two ways: both in the language communicating the project which I would argue is its specific ambiguity, and in the underlying postulation that the crisis that foreclosed the future was maybe not so much a question of content, but of form. Which is to say, underneath the exhibition and the language that surrounds it is the surreptitious postulation that maybe it isn’t so much the future, per se, that has been exhausted and shut down, but rather the ways in which we, by which I primarily mean western society, have come to talk about it: that it is the language we habitually use and the way we use it that have become impotent, sterile, and barren. And that if any kind of renewal were to take place, if any kind of faith in life after the present were conceivable, then maybe it could be found precisely in form, in the way certain things were not necessarily thought about, but more importantly, discussed. When I say discussed, I mean through form, syntax, grammar, and the deliberate embrace of ambiguity– none of which necessarily signifies the invention of new forms (or words) but rather highlights how they are conjoined and what kind of expectations we place upon them. Indeed, if this exhibition has any kind of essential thesis, any kind of theoretical bone to pick or axe to grind, it is this– a thesis which is itself (fortunately) incommunicable. I would say it could only be demonstrated, but that it is not really the correct word. Embodied might be better. The way a sentence is ultimately (invisibly) embodied by syntax.

Take, for instance, the exhibition’s overall title: The Registry of Promise. At once utterly specific and perfectly vague, it seems to signify something that exists and can be located. But where? Where is the registry of promise? What is its geographical locus, this conjecturable archive of promises? Can it actually be located? Or is it somehow virtual? If so, how to account for it? If it can’t be circumscribed in space, then perhaps it can be accounted for in time? But how? Who draws it up? Can it be quantified? All of the above are impossible to say. And yet, it would seem to exist, to designate something that exists but cannot be bounded in space or time, akin to St. Augustine’s oft-quoted conception of god– a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere. Whatever the case may be, it is for this very reason that the title, in accordance with Wallace Stevens’ famous injunction regarding the poem, “resists the intelligence almost successfully.”

This language and mode of reflection also extended to the titles of the four chapters of the exhibition itself, which dealt with specific aspects of the future. From The Promise of Melancholy and Ecology at the Fondazione Giuliani, Rome, which addressed the on-going trauma to traditional conceptions of nature, to the The Promise of Multiple Temporalities at Parc Saint Léger, Centre d’art contemporain, Pougues-Les-Eaux, which attempted to reconsider the notion of linear time. Whereafter there was The Promise of Moving Things at Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, Ivry-sur-Seine, which engaged ideas of animism and object oriented ontology, while the concluding chapter, entitled The Promise of Literature, Soothsaying and Speaking in Tongues, revolved around the very stuff of language, narrative, and the plastic materialization thereof.

Of the twenty three artists featured in the whole series, I had on one or more occasions worked with or written about more than half in the past several years. Some had been with me since I first started curating (in roughly 2007 or 2008), and we had evolved, or so it seemed, together, developing along parallel lines. This on-going continuity, I believe, is ultimately a question or byproduct of language, of kindred preoccupations, or merely trying to get at the same thing (in this sense, I am operating from a classical position, which is perhaps most succinctly encapsulated by a line from Goethe’s Faust: “You resemble the spirit you comprehend”). Perhaps it was also this sense of essentially haunting the same house that prevented the series from being an exhibition à thèse– and this in turn contributed to its ultimately personal nature (and this, the fact of being personal– a mode which according to contemporary standards of curatorial discourse is all but strictly verboten, of the most inviolable curatorial taboos– is something I have come to shamelessly seek out among every aspect of contemporary artistic production, thanks largely to the rebellious wisdom of Simone Menegoi, who taught me that the personal– not to be confused with the compiaciuto, the self-indulgent or self-satisfied– is essential to the irreducible quiddity of great art and curating. “Chris,” I have heard him solemnly observe on more than one occasion, “this is very personal work.” As if the very fact of it being personal mysteriously guaranteed its greatness, which lay precisely in its mystery. But I am getting way off topic….).

All that said, maybe I am just wasting a lot of language and the easiest thing to do is to tirelessly quote Georges Bataille, whom I have quoted elsewhere and will no doubt quote again, who best summarized what I am trying to do when he wrote (of stories but which, in my opinion, can be applied as much to art as to more traditional narrative forms):

“More or less every man depends on stories, on novels, which reveal to him the multiple truths of life. Only these stories, read sometimes in a trance, situate him before his destiny. We must passionately seek out what these stories can be– how to orient the effort by which the novel can be renewed, or better, perpetuated.”

The curator of The Registry of Promise would like to thank everyone who made this series of exhibitions as well as the forthcoming publication possible, starting with the directors of the institutions, Claire Le Restif, Adrienne Drake, Sandra Patron, Lorenzo Benedetti, and Roos Gortzak. A big thank you to all the galleries and private lenders who loaned works. A special thank you goes out to both Thibault Lambert and Léna Patier for all their help with communication, as well the designers of the communication, VLF Studio Paris, not to mention the many other people involved in the preparation and maintenance of these four exhibitions.