Four Stomachs at Objectif Exhibitions, 2015

On the first pass, cows barely chew their food. It’s a more protracted and mechanical process: they lap up grass; chew it; swallow it; regurgitate it; re-chew it; and then re-swallow it. “Chewing the cud” or “rumination,” a cow’s complex digestive tract remains in constant service.

From 14 February through 11 April 2015, Nina Beier’s solo exhibition, Four Stomachs, will not exactly conclude. Beier will place five large, polished brass casts in the ground floor space at Objectif Exhibitions—on the floor, to be exact. “Cows have four stomachs and forget their past, almost before it has passed,” and Beier’s annual shifting steadily followed a similarly ruminative procedure to its namesake’s intricate organs. 52 new works were produced in 2012, 2013, and 2014, then distributed to three rather disparate pastures. Yet for the palimpsestic fourth and final “stomach,” Beier has staked a more central field, and will introduce yet another 5 new works into the machine.

They’re comical. Elegantly honed and highly reflective, yet equally excretory and denatured, these invocations posture forms as old as dirt—poured in an evocative molten material that recalls much more. The polished gleam of musical instruments, the codification of a door key or, more metonymically, military hierarchy. Yet as depictions of earth, do they persist as exaggerated bases for monuments, or have they been elevated to the status of that which they previously served to uphold (in its absence)? If so, what do they now symbolically commemorate beyond that absence—the time-lapsed reduction of monuments to meeting points, the growing confusion between the map and its territory? Any cast metal is based on a clay figure of some sort, so while these depictions of mud—cast in actual mud (clay)—appear here as positive forms, can they also conjure the negative forms they’ve left behind?

In contrast to Beier’s three previous “stomachs,” which she sited in three different and much less traditional spaces, she chose the ground floor location at Objectif Exhibitions for the supposed “neutrality” of its white walls, and for its prescribed function as an exhibition space. Meanwhile, as representations of dirt, vignettes of earth, her new series is itself already an agglomeration of implied locations—both figure and ground, and at once both literal and figurative.

Chew, swallow, chew. To retrace Beier’s steps, she spent 2012 defacing a series of bronze, plastic, ceramic, and fiberglass busts. She positioned these Facing Figures above Objectif Exhibitions, within the residential apartment windows of our neighbors, whenever an intrepid resident decided to become involved. A bust is always born disfigured—limbless, partial, abstracted. Beier disfigured them further, and stripped them of their authorship, their referents, their likenesses, their histories.

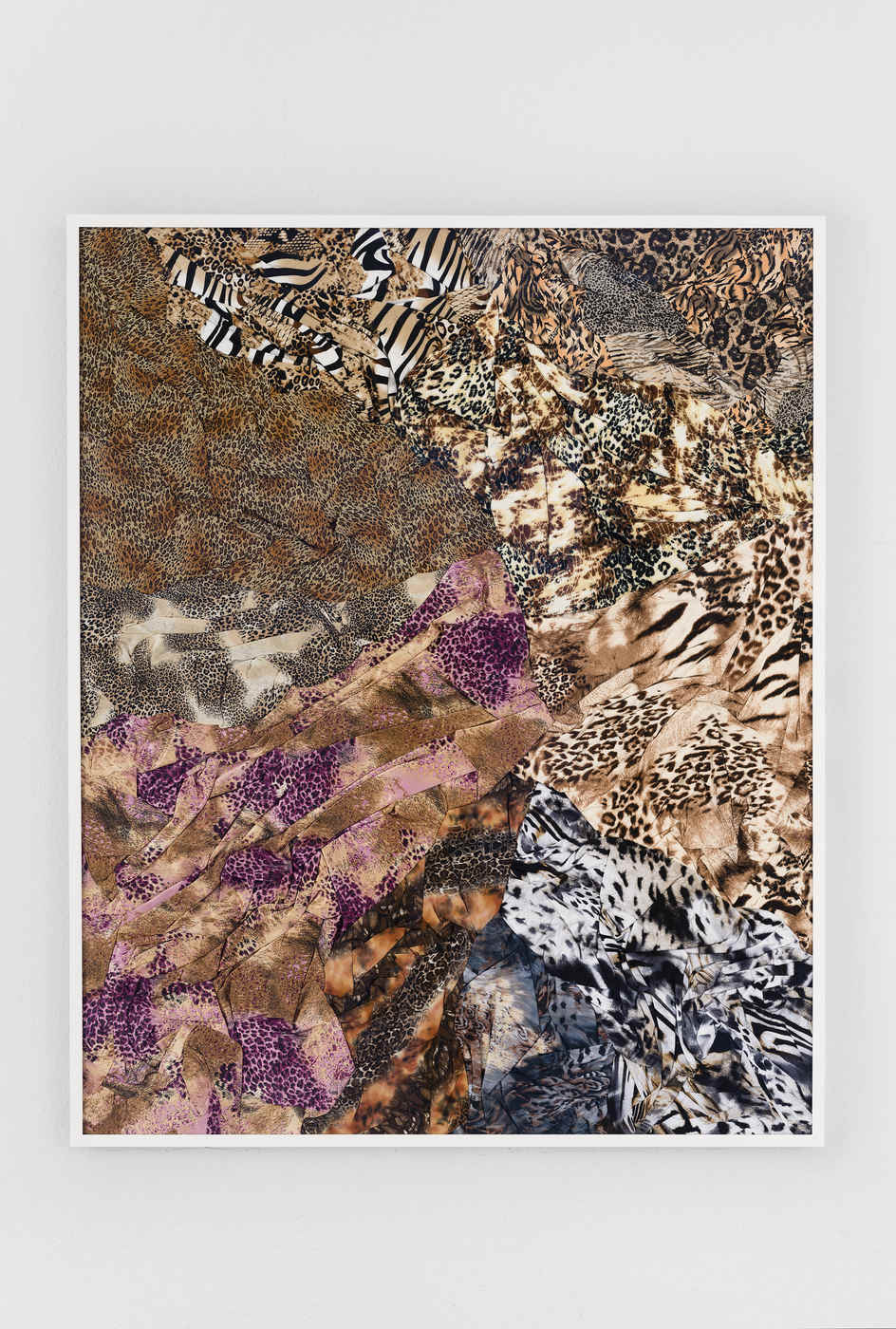

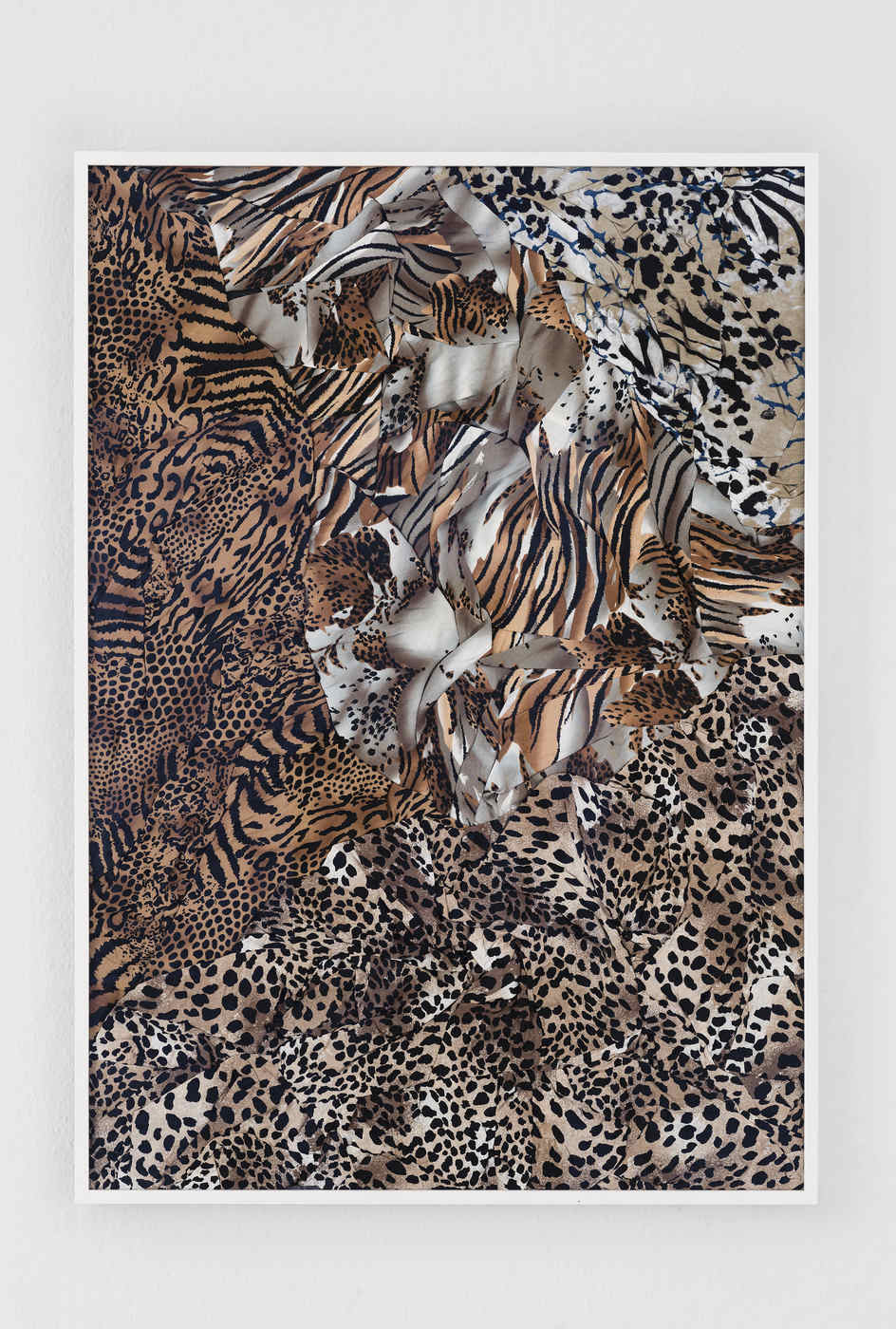

In 2013, Beier removed her eyeless sentinels from the courtyard windows, and dispatched a rather different herd to sartorially squat an even more private residence—director Chris Fitzpatrick’s apartment at Riemstraat 3, in 2000 Antwerp. Vertically oriented, human-scaled, these seven overstuffed Portrait Mode frames sealed discarded animal-printed apparel behind glass—“trophies” displayed behind the lock and key of the gatekeeper she contracted to domesticate the lot “by invitation only.”

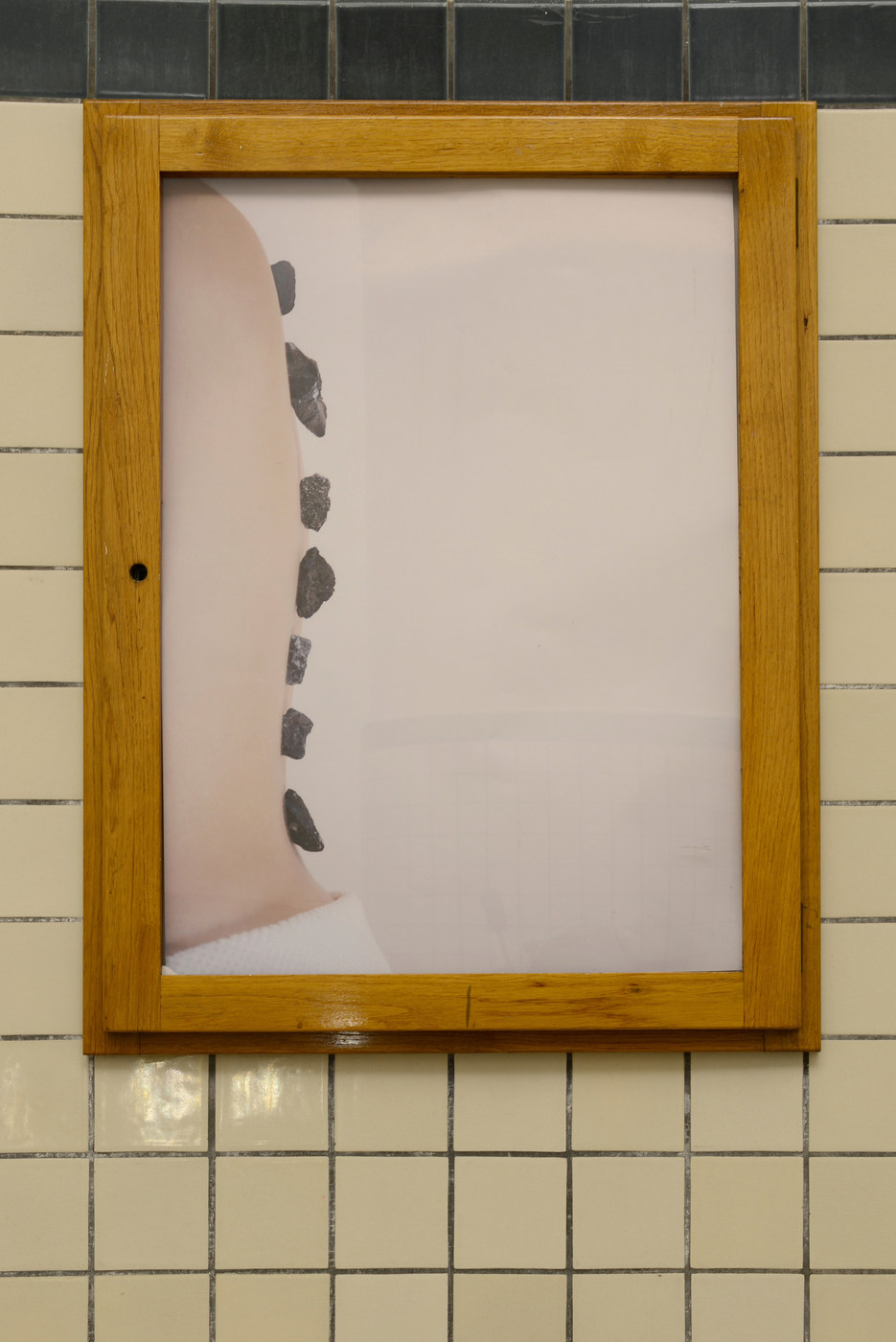

In 2014, Beier opened the third of her four “stomachs” far wider, and to a larger unsuspecting populace of commuters. She assumed the photographic language of royalty-free image-banks by absurdly parroting and exaggerating a familiar motif, and produced 33 full-color posters, or Variations. Publicly displayed without mention or mediation, and at intervals choreographed solely by access and availability, her posters were rotated in and out of the staggered advertising frames flanking the escalators on either side of the Sint-Annatunnel—a 1930s subaquatic pedestrian tunnel beneath a river in Antwerp.

At its most basic level, Four Stomachs is the result of an organization committing to an artist’s practice for a longer period of time than normal—offering not only itself as a context, but potentially the entire city and community the organization serves. As a result, all space was available as a medium, but also an exceptional amount of time. Amid the four-year duration, and through the system she developed for working within it, the moments of conception, realization, presentation, and reception were collapsed into one interconnected phase—a phase both independent of and inextricably tied to all the many other activities Objectif Exhibitions has produced simultaneously.

Last year, last “stomach.” Yet Beier denies resolution by deferring to a more standard 8-week timeframe instead, and later, by including the new work she devised for Objectif Exhibitions in other exhibitions at other institutions, in other contexts, and at other times, within 2015. She interrupts the expectations surrounding her “four-year” exhibition, and retains control over its trajectory—veering its tract away from conclusion, via dispersion. She beats it into the ground.

Four Stomachs at Sint-Anna Tunnel, 2014

Nina Beier does not stop digesting. “Altogether, Four Stomachs is a machine,” yet in 2014, Beier’s four-year exhibition becomes an entanglement of concentric machines. And she’s opening the third of her four “stomachs” far wider.

Beier spent 2012 defacing a series of bronze, plastic, ceramic, and fiberglass busts and positioning this growing population of Facing Figures above, within the residential windows of our neighbors. A bust is always born disfigured—limbless, partial, abstracted. Beier disfigured them further, and stripped them of their histories.

“Cows have four stomachs and forget their past, almost before it has passed.” And in 2013, Beier pushed her eyeless sentinels out to pasture, and dispatched a rather different herd to sartorially squat an even more private residence. Vertically oriented, human-scaled, these seven overstuffed Portrait Mode frames sealed discarded animal-printed apparel behind glass—and all of it behind the lock and key of a gatekeeper she contracted to domesticate the lot “by invitation only.”

Now it’s 2014, and Beier will be inserting a shifting array of full-color posters into the year, at intervals choreographed by access and availability. These posters will rotate through the many staggered advertising frames flanking the escalators on either side of the Sint-Annatunnel—a 1930s subaquatic pedestrian tunnel beneath a river in Antwerp.

Beier assumed the photographic language of royalty-free image-banks. These online troves are filled with ambiguous, yet suggestive, imagery—empty metaphors created for uses unknown to their authors. Uploaded into this cyclical, cannibalistic system, their clichés detach from any particular reference. Here, how an image is advanced in complexity by other stock-photographers—that is, how the essence of a given motif is copied and warped—is key.

Absurdly parroting and exaggerating a familiar motif, then inserting it into a seemingly fitting context, Beier drowns her images. Subjected, intention falls away. All options become permissible, plausible—valid. And interpretation is inscription.

Four Stomachs at Director’s apartment, 2013

Nina Beier does not complete exhibitions. If parenthetically corralled, “(but so does Beier)” was not an afterthought dropped into last year’s text, but a signal foreshadowing this year’s transition from one stomach to another. Preceding a full stop, the () suggested an ellipsis leading to an even tauter entanglement of public/private.

“Cows have four stomachs and forget their past, almost before it has passed.” Yet one year later, Nina Beier’s Four Stomachs remains a machine, and Beier still prods the parameters. Methodically disfigured, those dozen eyeless sentinels performed their public service, and Beier has pushed them out to pasture.

They’ve been replaced by seven large works from Beier’s Portrait Mode series. Vertically oriented, human-scaled, Beier has arranged for this line of frames—bulging and overstuffed with discarded animal-printed apparel she sealed, this time, behind less reflective, more protective, glass—to sartorially squat the director’s private residence. Resembling the most haunted of trophies, this stable of compressed skeuomorphic garments is tended by a gatekeeper contracted to live within a growing series of questions—economic, aesthetic, conceptual, professional and, as so few will ever see, domestic.

Four Stomachs at Objectif Exhibitions, 2012

Nina Beier does not complete works. They remain subject to re-use, re-titling, re-articulation, and reanimation. With Four Stomachs, Beier defaces a series of busts (bronze portraits, plastic mannequins, ceramic figurative folk art), and positions them in the residential windows above Objectif Exhibitions.

Cows have four stomachs and forget their past, almost before it has passed. A bust is always born disfigured—limbless, partial, abstracted. Beier disfigures them further, and strips them of their histories.

Placing the flattened faceless fronts of the figures flush against the window glass, Beier symbolically seals their exposed inner surfaces—containers contained. Observing like eyeless sentinels or debilitated gargoyles, they too will be watched—fixed in place, or periodically shifting locations—over the next four years.

Altogether, Four Stomachs is a machine. Sentient, it reserves the right to restart itself at any moment, or to halt completely (but so does Beier).