Artist: Simon Dybbroe Møller

Exhibition title: Lettuce

Curated by: Severin Dünser

Venue: 21er Haus (21er Raum), Vienna, Austria

Date: December 5, 2015 – January 31, 2016

Photography: images copyright and courtesy of the artist, 21er Haus and Belvedere, Vienna

„We look at everything with photography. When we see a black piece of marble, often used in wet spaces and at memorial sites—bathrooms, kitchens, and graves—we notice its glossiness. It is so photographic. Look at its white veins, the snail shells, the mussels. See how it resembles a print made from a damaged negative. This is photography avant la lettre.

Of course, photography is different now. The growing breed of male tech enthusiasts posting online reviews of new camera equipment is inhabiting a complicated territory. In order to investigate and discuss the visual capabilities of the constant stream of new digital gear, they have to point their lenses towards something; they have to choose a motif. They mostly choose women or birds.

A cormorant drying its wings on an old withered wooden pole, for instance: the Jesus- like silhouette and the pride of its posture mirrored in the water surface. A truly pathetic image. It is said that the cormorant is the most ancient bird around; that it dates back to the dinosaurs. That unlike other aquatic birds it has not developed the oil sheen that would protect it from becoming soaked, hence the crucifix-like pose: it does so to dry its feathers in the breeze. What an anachronism. A more constructive voice would frame it differently and explain how most creatures are naturally buoyant, but how for diving birds this is an issue. The cormorant is thought to swallow pebbles to increase its weight. Its main adaptation, though, is its open feather structure that does not trap buoyancy-increasing air but absorbs water instead. Regardless: imagine soaked feathers. Conversely imagine water droplets on a water-repellent surface. Let us think about this in relation to analog and to digital image making.

Perhaps the wet white t-shirt was the climax of old-world sleaziness. A last spasm of the analog before our descent into the weight- and age-less universe of silicone and Botox, the taxidermy of the technosphere; into the waxed universe of the virtual. Do you remember Sabrina and Boys Boys Boys? Can you recall Samantha Fox? The way those singers exploited white cotton and water to produce images of their shapely bodies both concealed and enhanced. Images that seemed to transcend the slick surface of the glossy magazines by echoing the fluidity of analog processing and the stickiness of the emulsion coat of a photographic print. Tits and ass or draperie mouillée. A century earlier the realist Constantin Emile Meunier modeled his monumental sculpture The Dock Worker, depicting the toned figure of his subject draped in moist, clingy garments. In this fantasy even the soggy is solid, the saturated is steely. The patina of the bronze reminiscent of a vintage sepia-toned black-and-white print; the lack of tonality melting the body with the cloth.

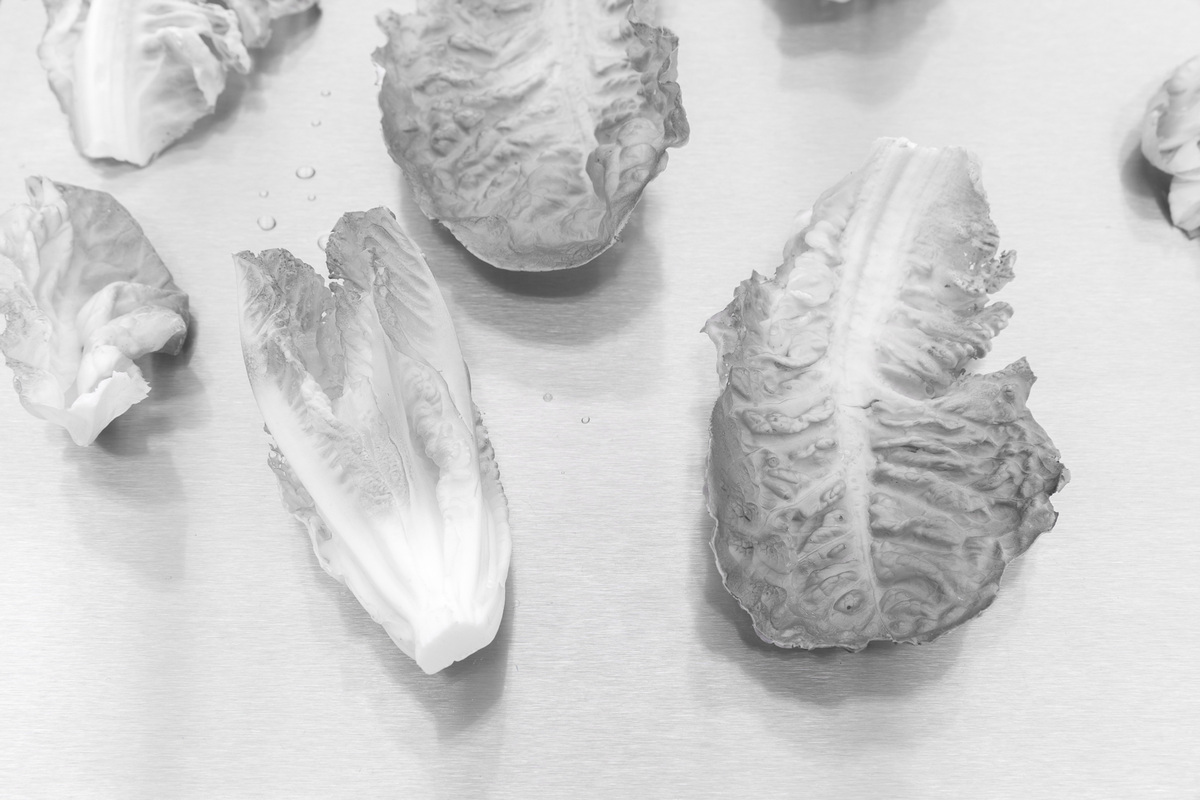

It is surely no coincidence that perfectly contained drops of liquid sitting on surfaces of things feature so heavily in digital image-making tutorials. Like the techy garments used in the outdoor sports industry, these images inhabit a landscape of impenetrability. We know that the perfect water drops on the bright green leaves adorning our computer desktops did not occur naturally. That they were placed there, then elaborately lit. Possibly they are not water at all but either gelatin or resin or pure digital post-production. Even when sitting on an absorbent surface they do not soak things; they do not evaporate into the air. We are dealing with digital image making here, with ideals. No earth to earth, but a world where things have borders, a world without entropy, a universe without decay. Like fresh lettuce lying on a minimalist polished steel kitchen countertop—its white veins piercing through the neon green translucent hue of its leaves, its objecthood amplified by the mirroring metal surface— so low in calories that digesting it requires the same amount of energy as it contains.“