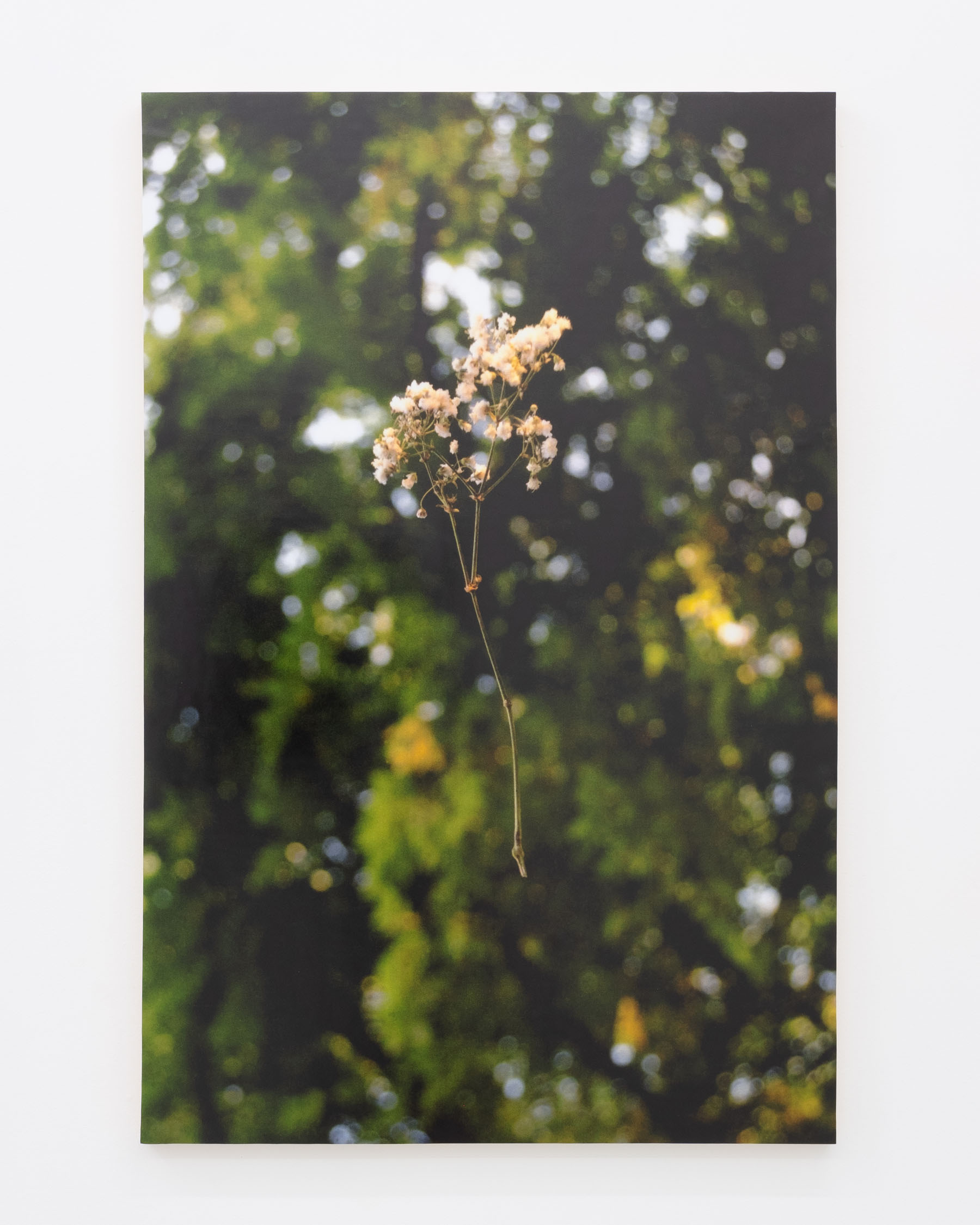

Bouquet for flowers

Some plants secrete oils to communicate. In dry weather their oils carry signals that spread out through the soil, warning root systems to rest and seeds to stop germinating. When rainwater falls it dissolves these oils, splashing their residue into the air with a selection of other compounds. This mixture makes the smell of fresh rain, a smell of plants remembering to grow.

✿✿✿✿✿

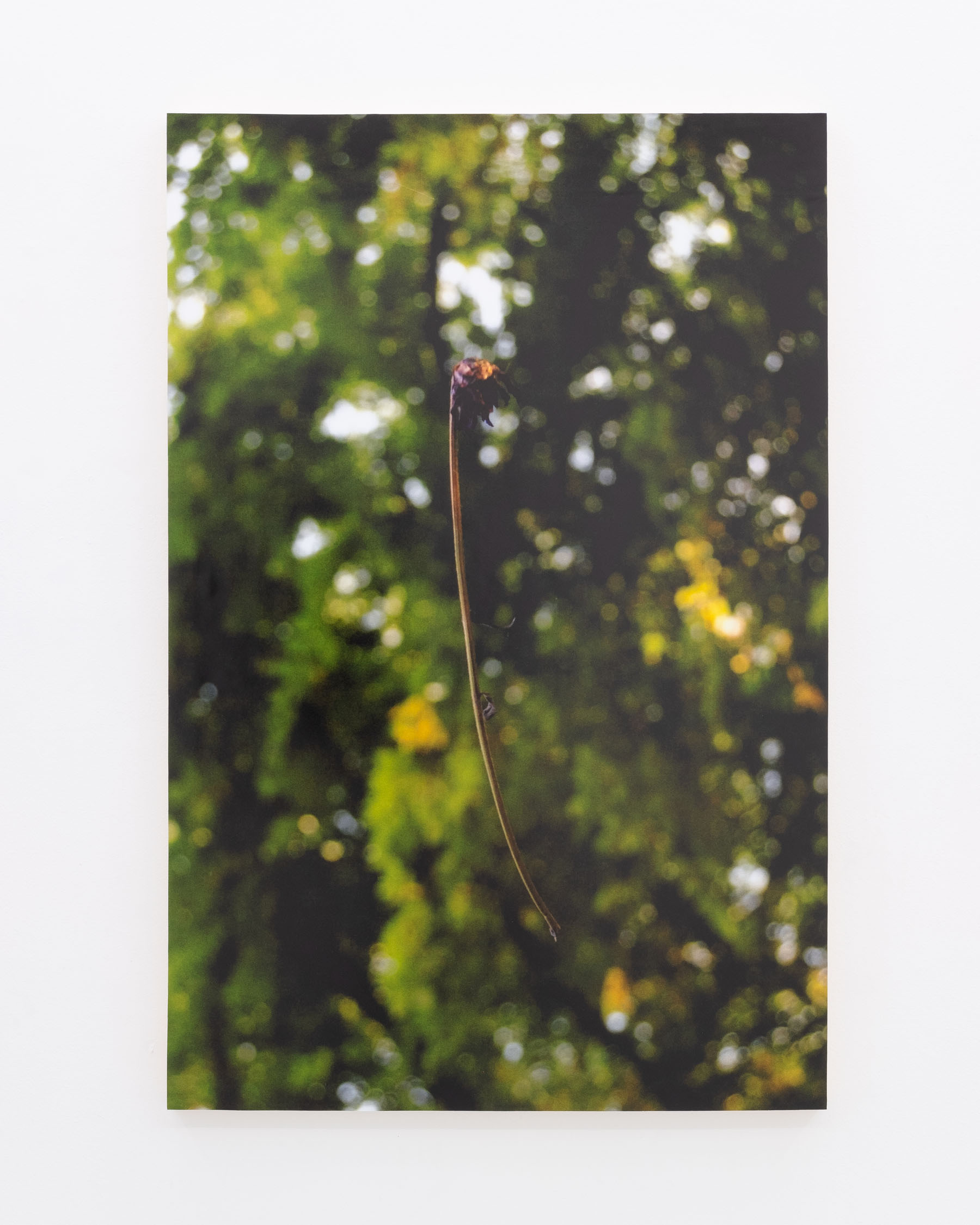

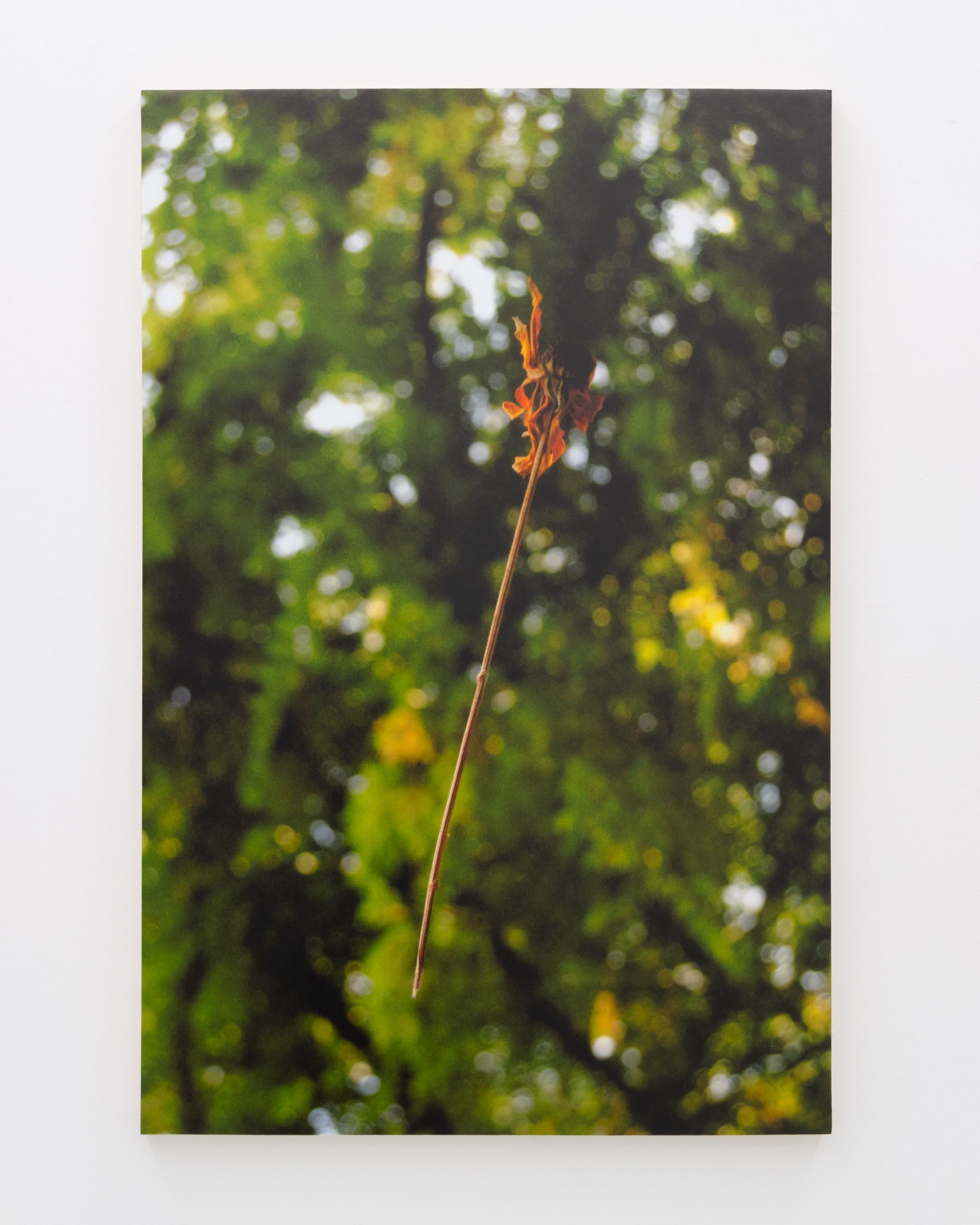

Paths in the cemetery were often damp with rain. Like lines on a hand drawn grid they were paved in a series of unequally shaped rectangles, with blocky metal chests spaced out along their edges. The metal chests were two feet tall by two feet wide and designed to blend with their surroundings, their flat walls painted green to match the grasses. Up close the middles of the chests were hollow and divided, housing separated bins for garbage and compost. The garbage bins collected coffee cups, bags from the area’s dog walkers and empty takeout containers. The compost held snapped stems and shriveled petals from discarded flowers. In the summer these flowers looked brittle, their colours faded, their bodies so vacant of water they might have floated if they weren’t pressed down. In the fall and winter they were heavier, their purples, yellows, blues and whites all sludging up in clumps.

The cemetery was quiet, and the largest green space near my studio: four blocks south from our back door, a right turn at 31st, then left through a hole in the fence halfway down. For five years I walked there regularly, forming a habit of checking the flower bins. I saw the flowers in the bins as vessels, temporary holders for the memories, love and grief of their givers. I also saw them as individuals with stories of their own, their lives over, their bodies preparing to dissolve.

✿✿✿✿

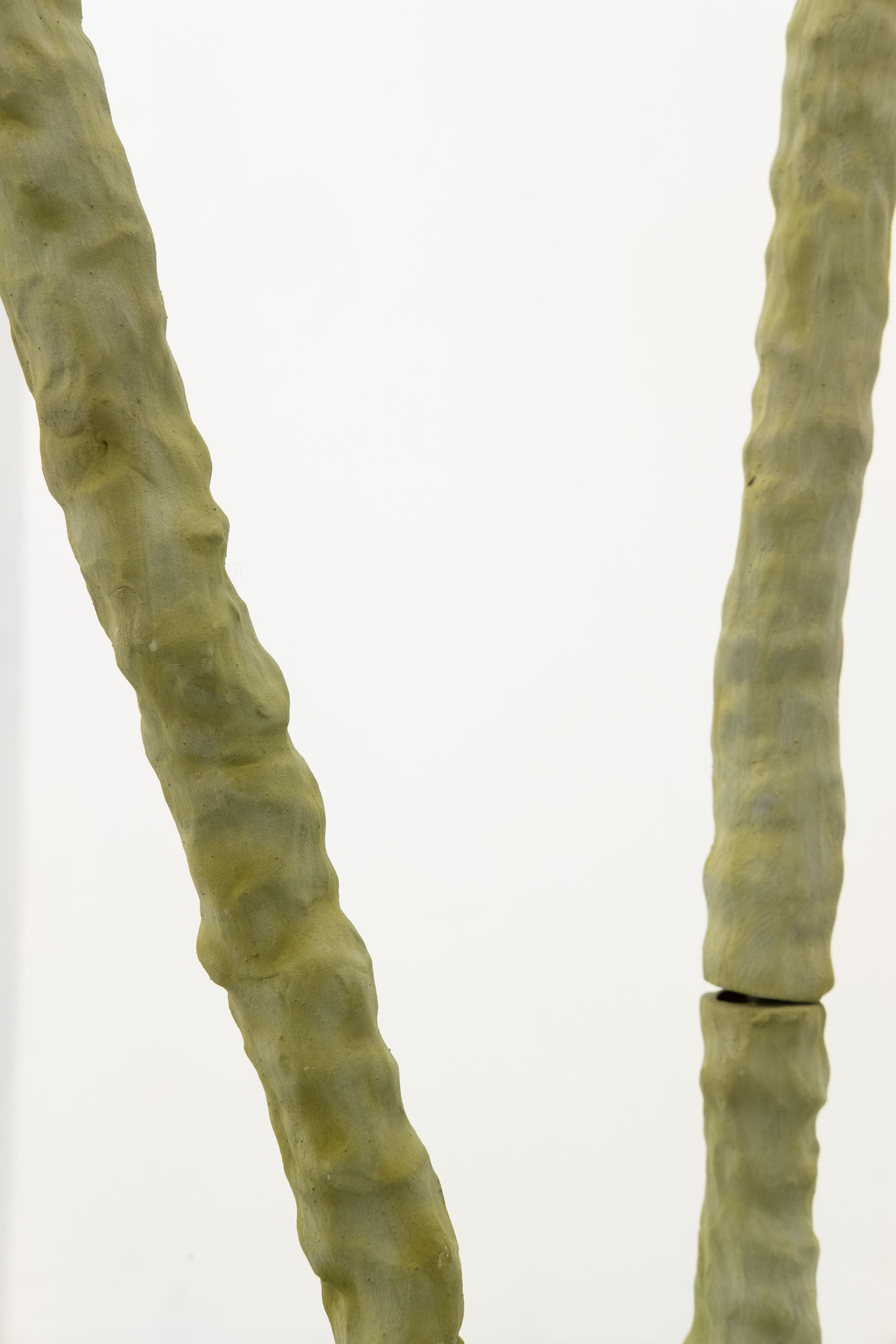

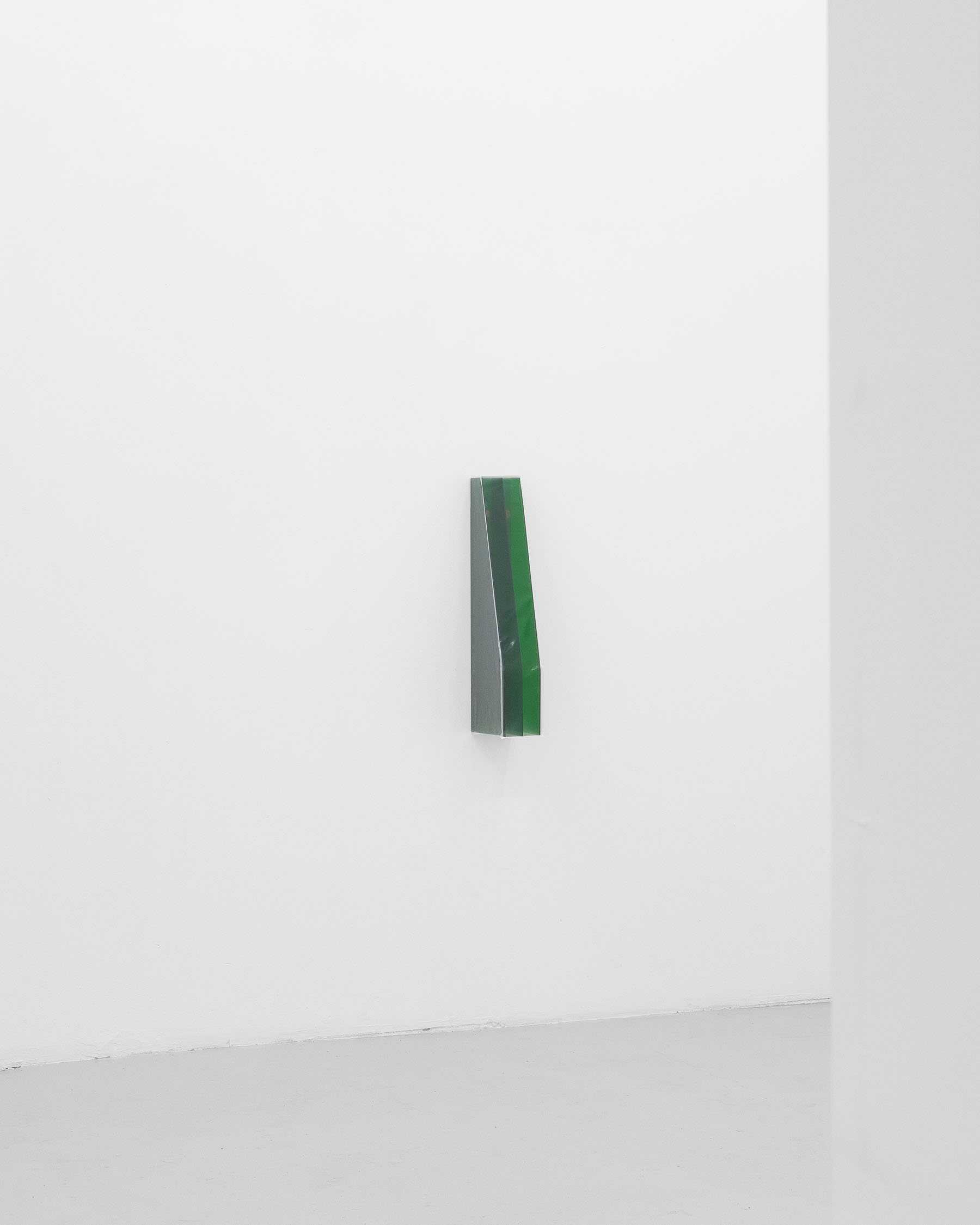

One summer I picked a handful of flowers from the bins and brought them back with me to the studio. They hung there for weeks, pinned to my wall in a ripped canvas tote. After a while I removed them from the tote, took their measurements, then returned them to their bag. I thought about them at work, spending lunch breaks reading about flower life spans, cut flower auctions and preservation methods on my phone. Back at the studio I borrowed my studio mates’ tools, cutting up sheets of clear acrylic and building square, rigid containers to fit each flower’s dimensions. Once these were built I took the flowers from the tote again and placed them inside their new containers. I flooded the containers with a mixture of chemicals and distilled water then sealed the flowers in, a process adopted from my lunchtime searches. I had decided I wanted to keep the bodies of the flowers from disappearing; my chemical mixture was supposed to stop the flowers’ decomposition, indefinitely holding them somewhere on the bridge between death and decay.

When all the containers were sealed they got included in a group show. The exhibition was up for a month. After it closed the containers were returned to me. I packed them away in a cardboard box for safekeeping.

✿✿✿

Two years went by and my studio’s lease expired. Our landlord doubled the rent, forcing my studio mates and I out. Most of us moved to another building, in an area with far less green space. Shortly after that I moved away.

✿✿

When I came back to the city some time later I took my box of containers out of storage. This effort from years ago, to build an artwork exploring death and memory by intentionally halting the decomposition of another living thing—my understanding of the gesture had changed. It had started feeling wrong, almost perverse, to continue keeping my flowers from their natural cycle.

I opened the cardboard box with a paring knife, slicing apart taped-over edges then peeling the top flaps back. Pulling my pieces out one by one I found the containers had grown contorted, their original forms completely changed. Once square walls were rippled and twisted, sucked in at places and bubbled out at others. Cracks had traced thin lines everywhere on their surfaces, letting fluids seep out or evaporate away. The flowers remained, trapped in empty cavities, their bodies no longer preserved. Searching around I found a hacksaw to cut apart the plastic. Extracting what was left of the flowers, I returned them to the compost.

✿

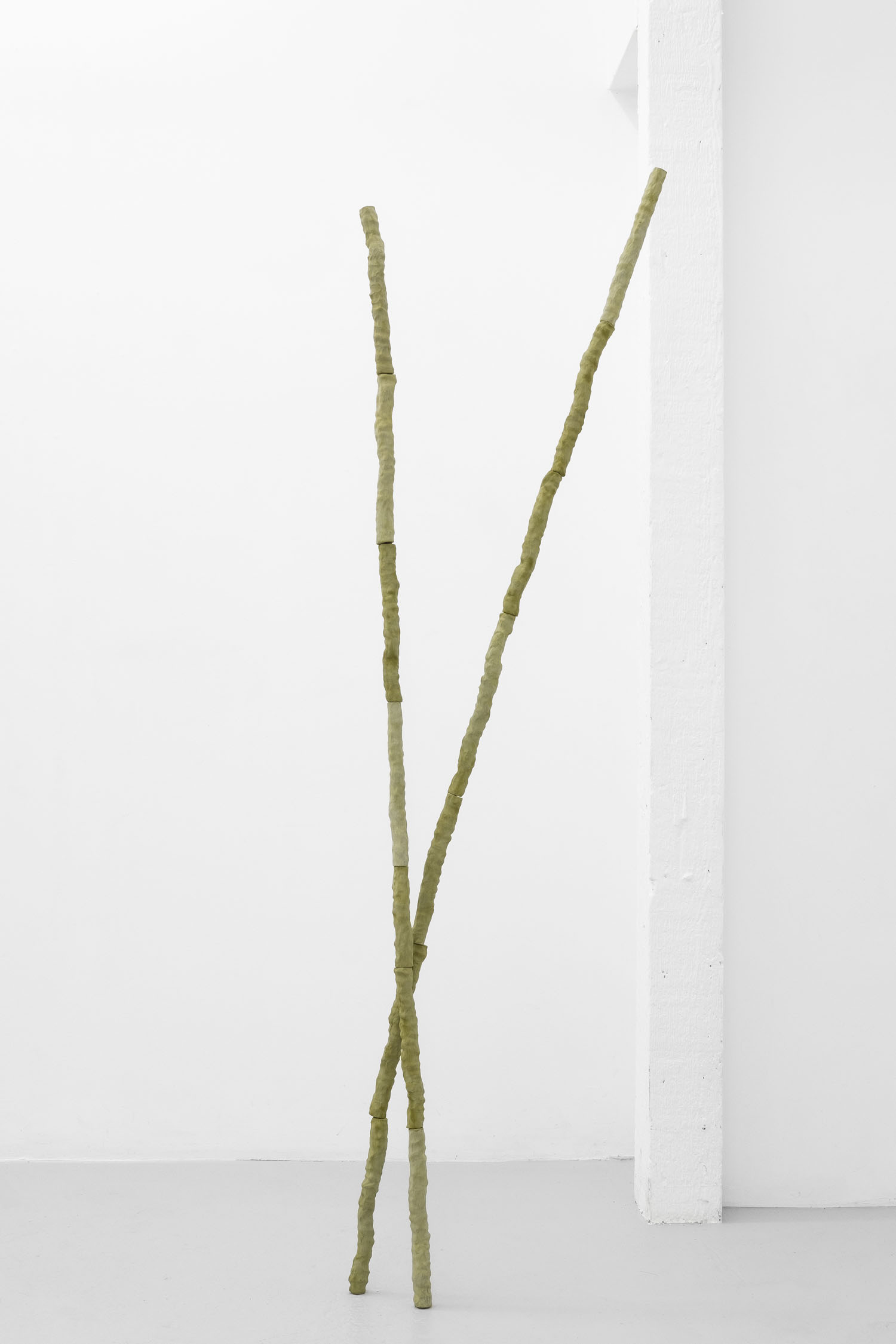

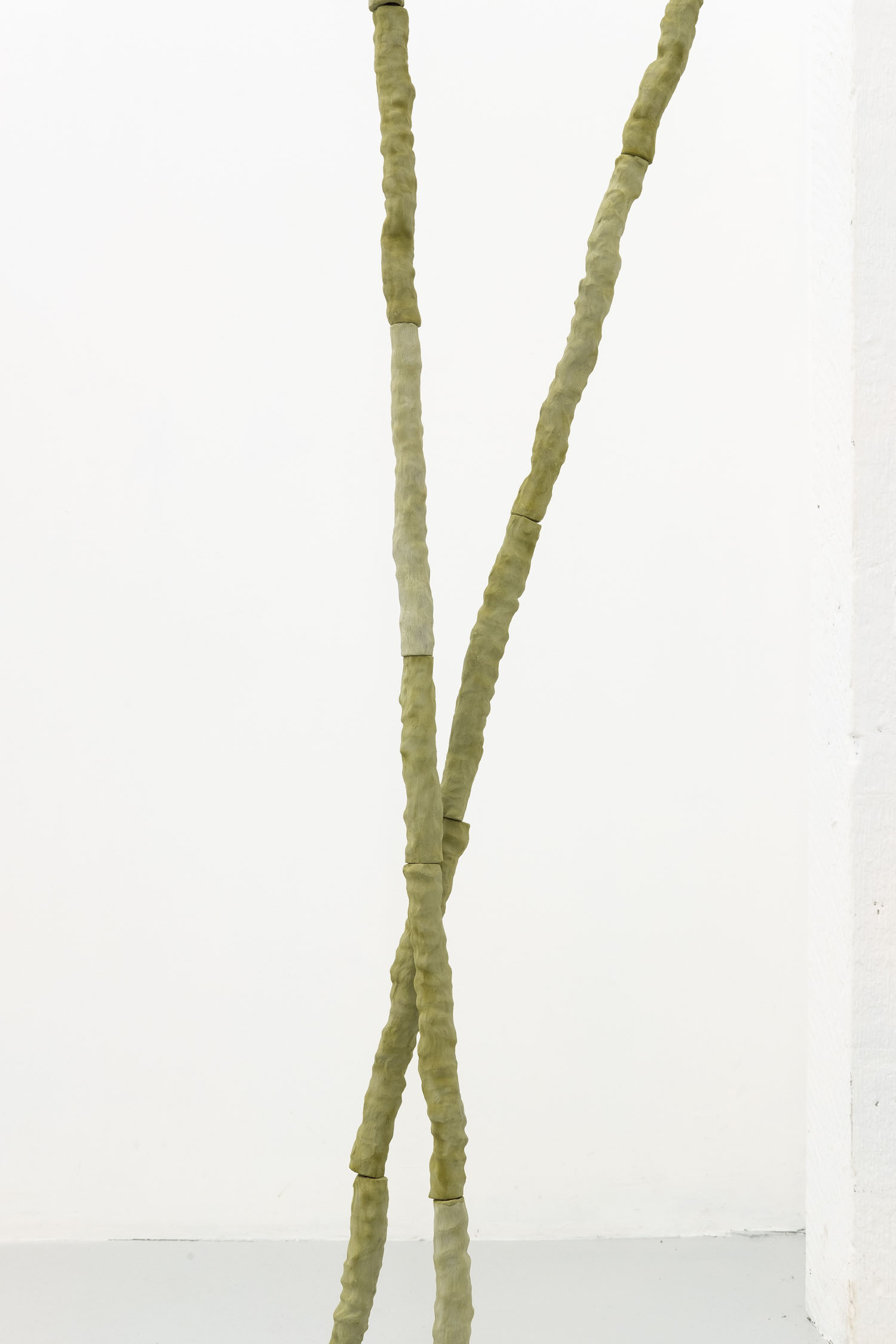

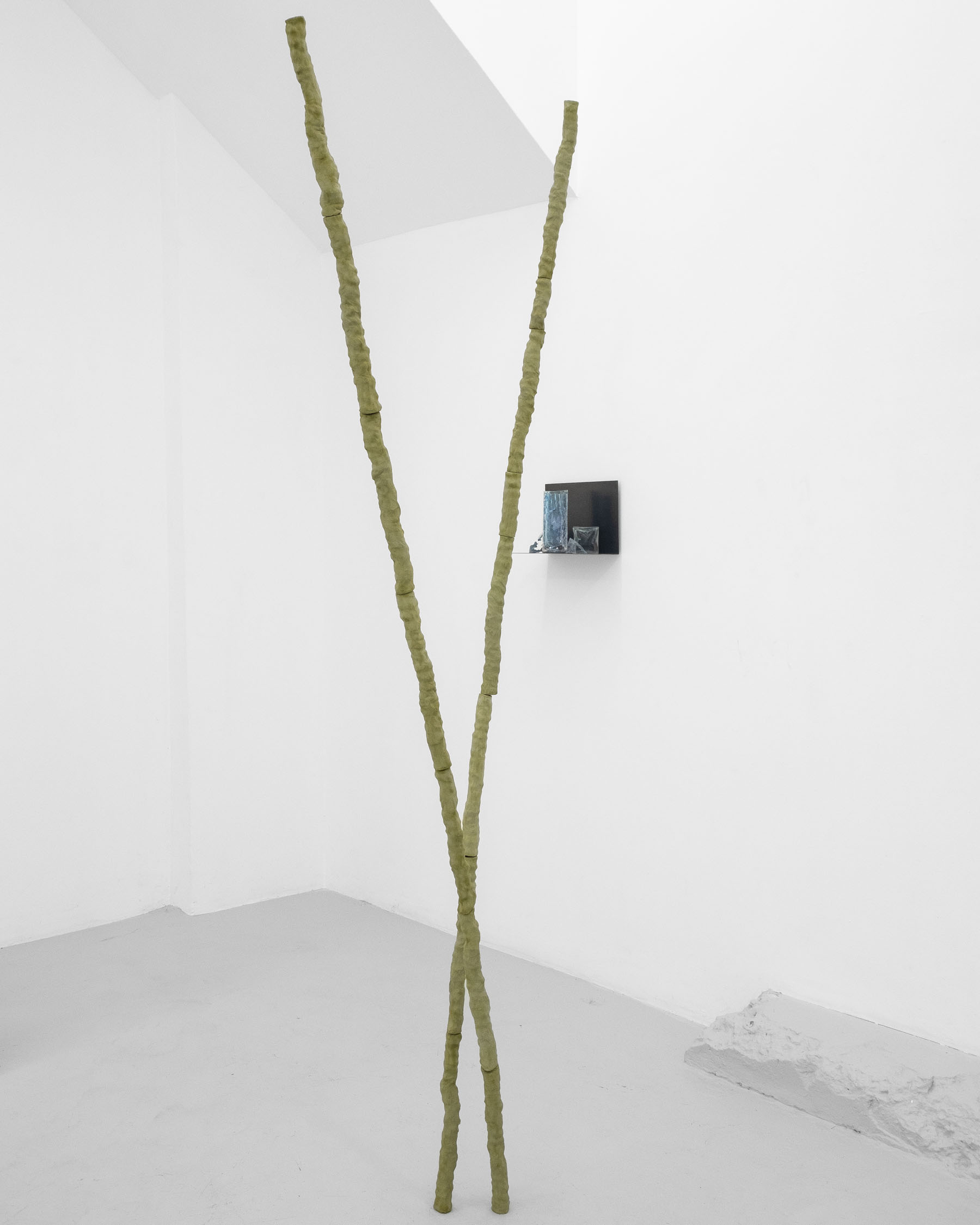

Scott Kemp (b. unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations | Vancouver, BC) is an interdisciplinary artist who experiments with sculpture, printed image and video. His art practice dialogues with science, pseudo-science, graphic design and other systems of belief. From 2014 to 2020 he organized exhibitions, performances, screenings, readings, dinners and concerts in his home city. Since then he has concentrated on his own artwork, a path which has allowed him to build many new and positive relationships. His recent projects have also been concerned with relationships, exploring various registers of human connection – interpersonal, geological, spiritual. Central to these projects is an interest in moments where the porosity of the human body becomes visible, and where perceived separations between the Self, the Other and the Environment begin to blur.