The past crumbles, sediments, re-emerges and shapes the landscape; it dissolves into strokes of colour. It does not simply haunt the present: it is a constitutive part of it.

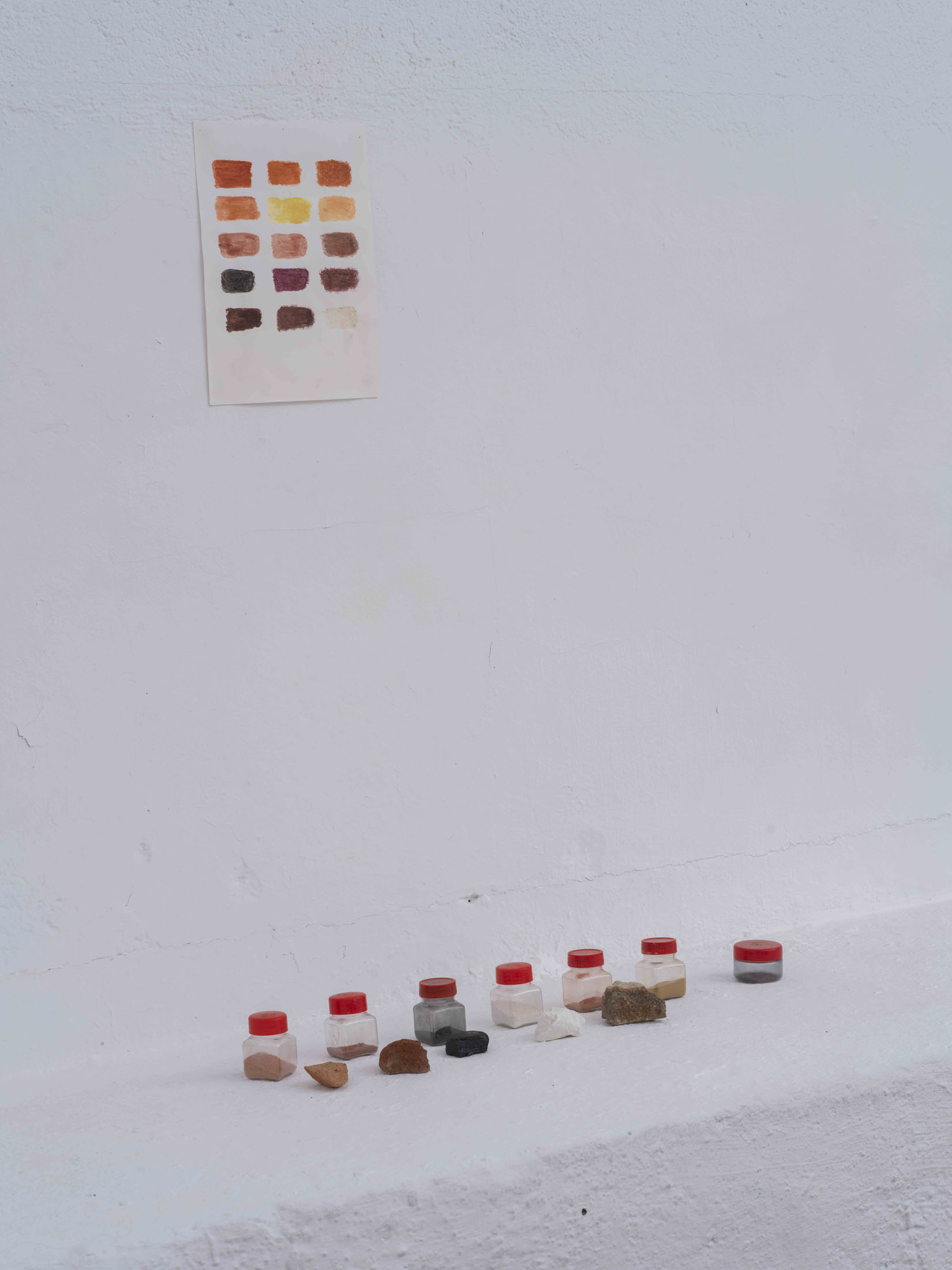

In this new series of paintings, British artist and researcher Robert Mead proposes a multifaceted exploration of temporality, the simultaneity of presence and absence, corporeality and spectrality, and cumulative environmental change inspired by the coastal landscapes of East Anglia in the United Kingdom. The collection welcomes the spectral aspects of existence; looking at the paintings, we are reminded that the living are but ‘ghosts on temporary reprieve’. By using a selection of pigments harvested from the very East Anglian landscapes that inspire his work, Mead layers the past and the present, materiality and abstraction, memory and creation.

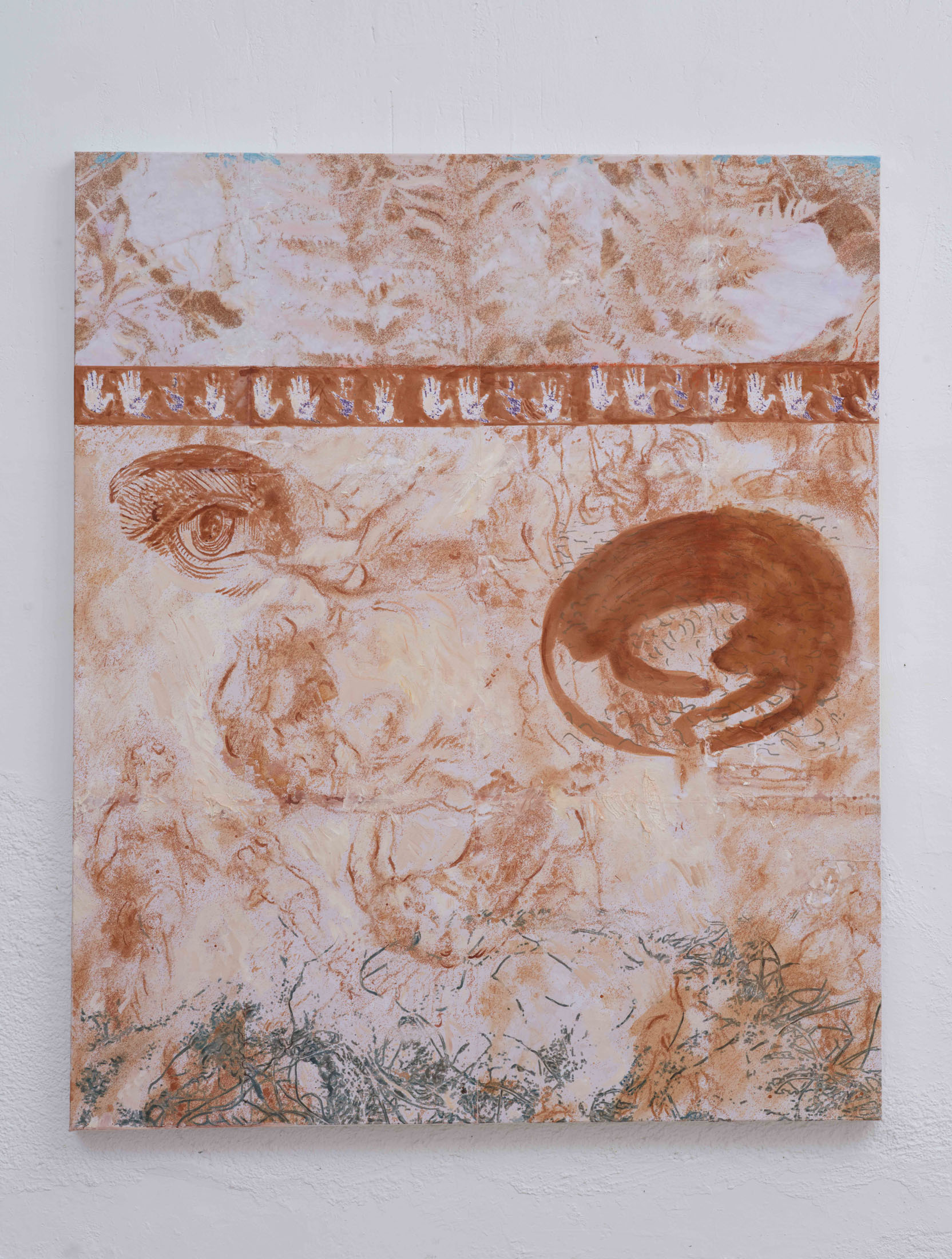

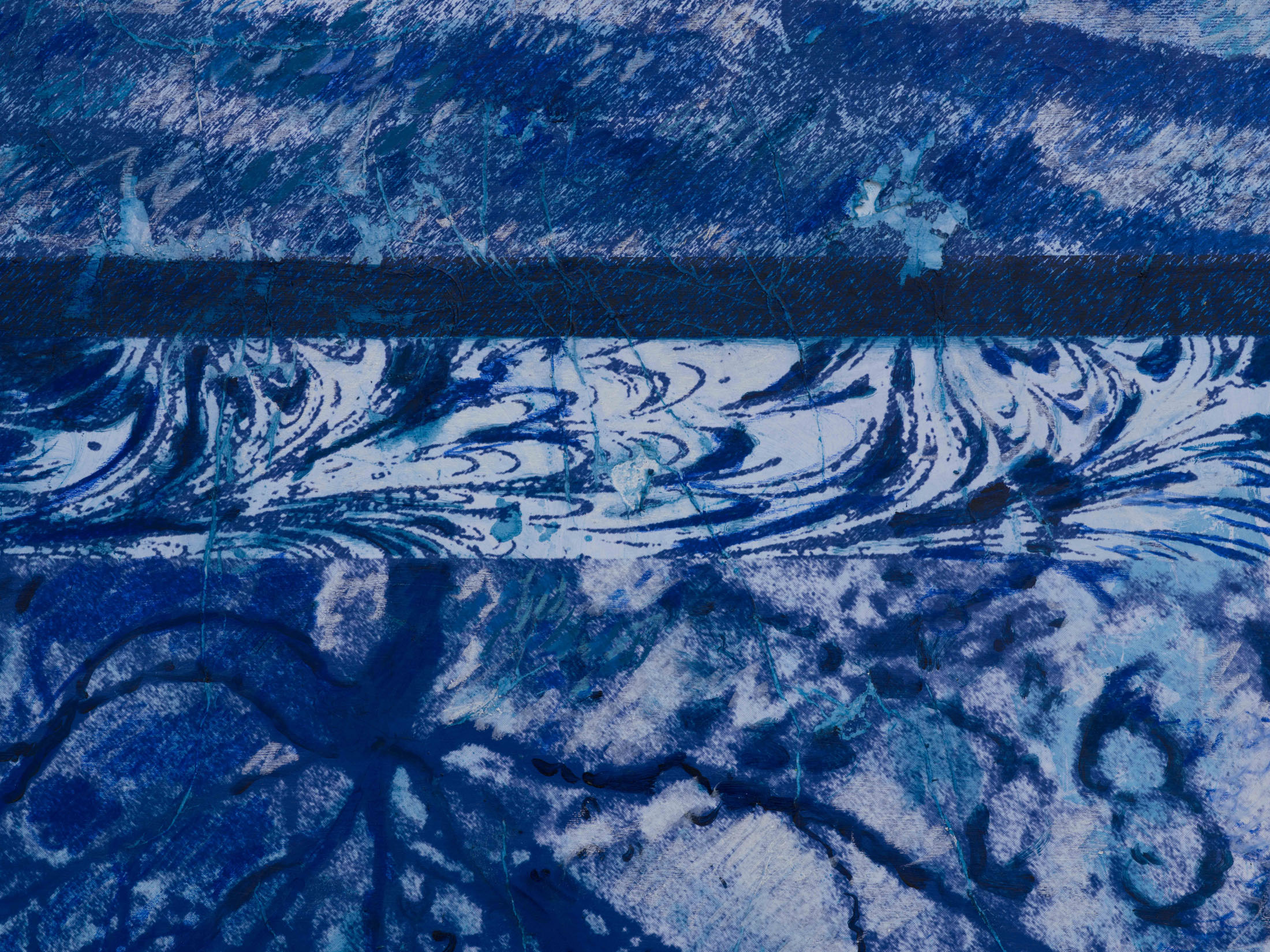

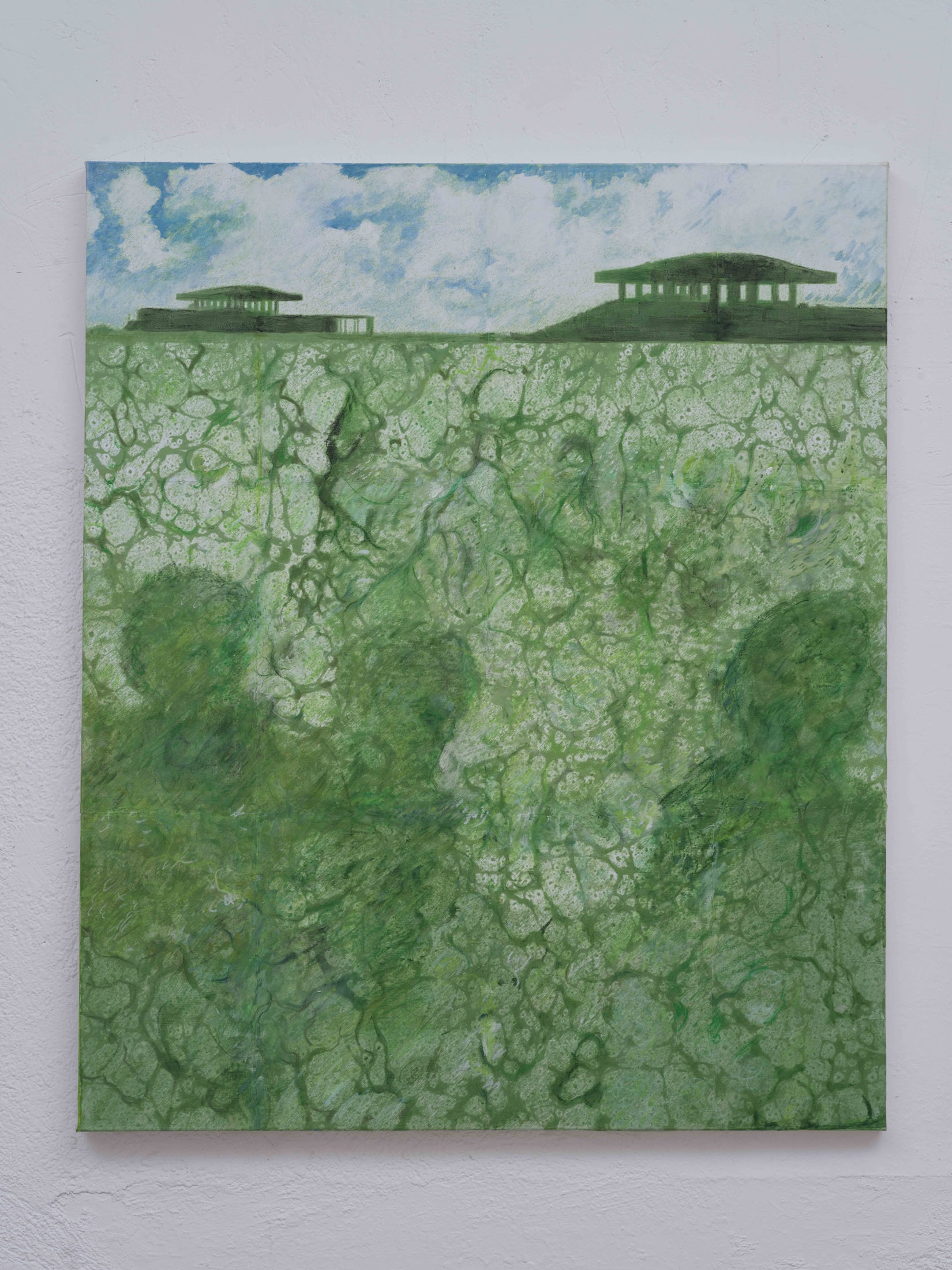

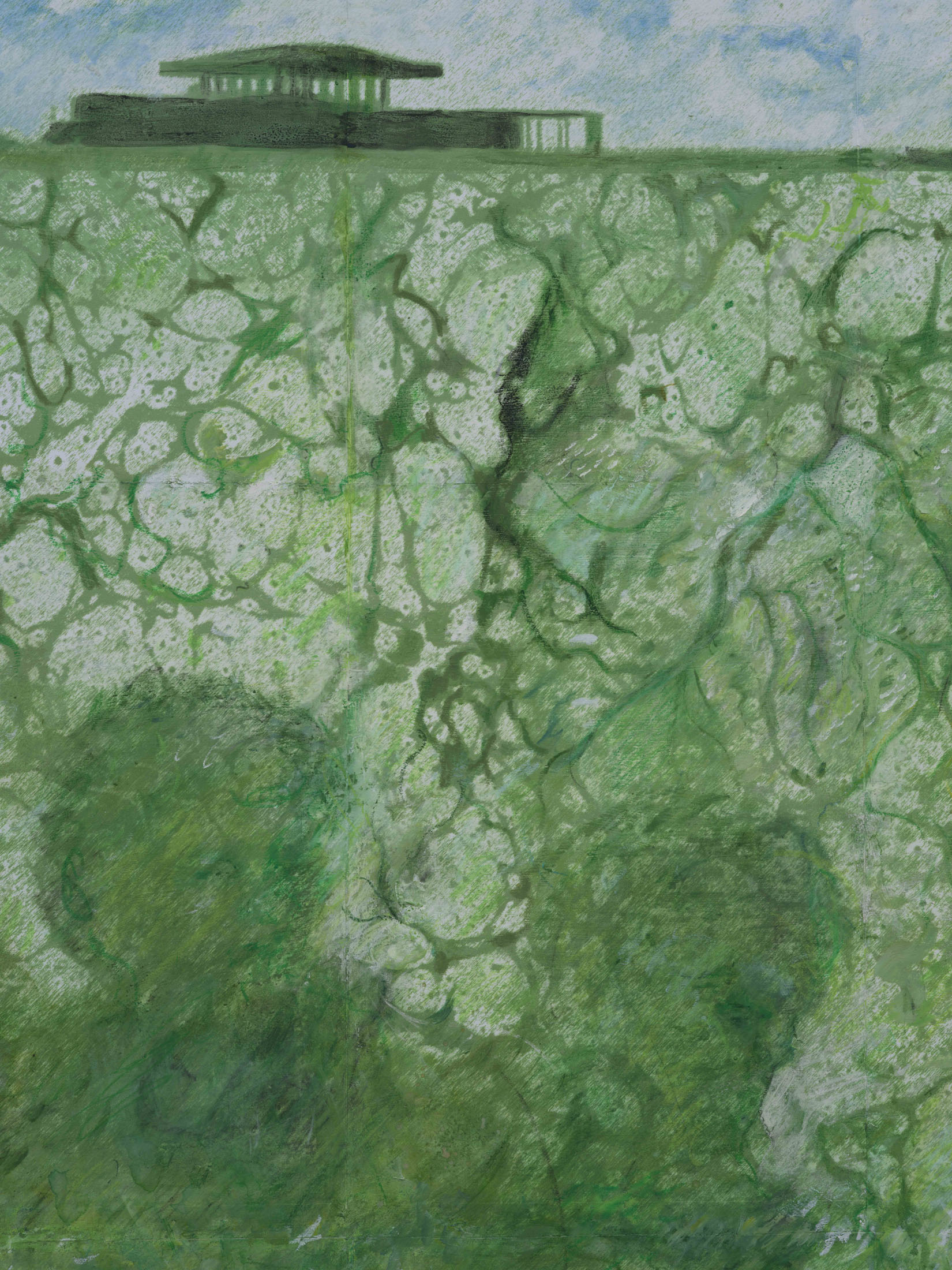

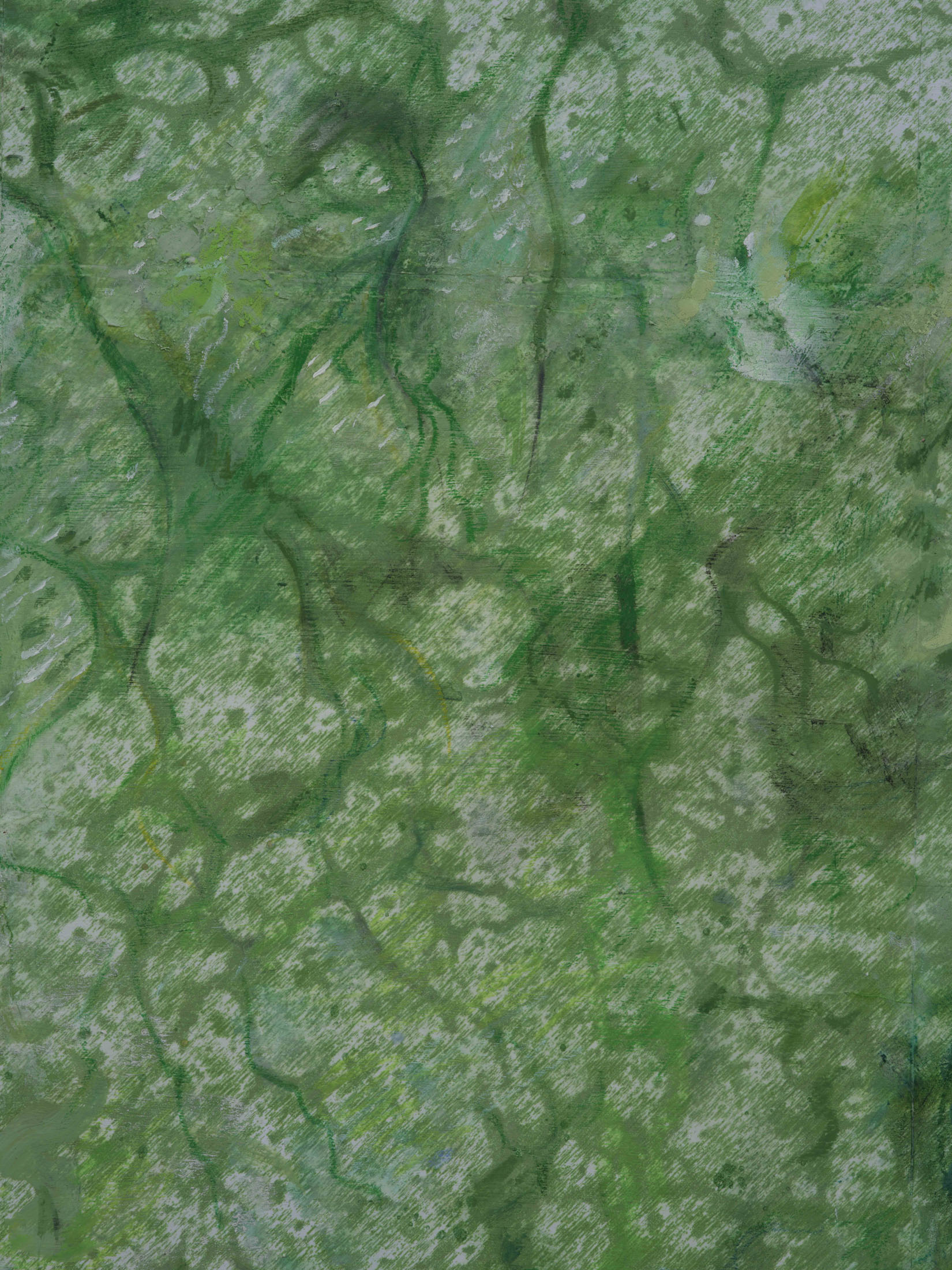

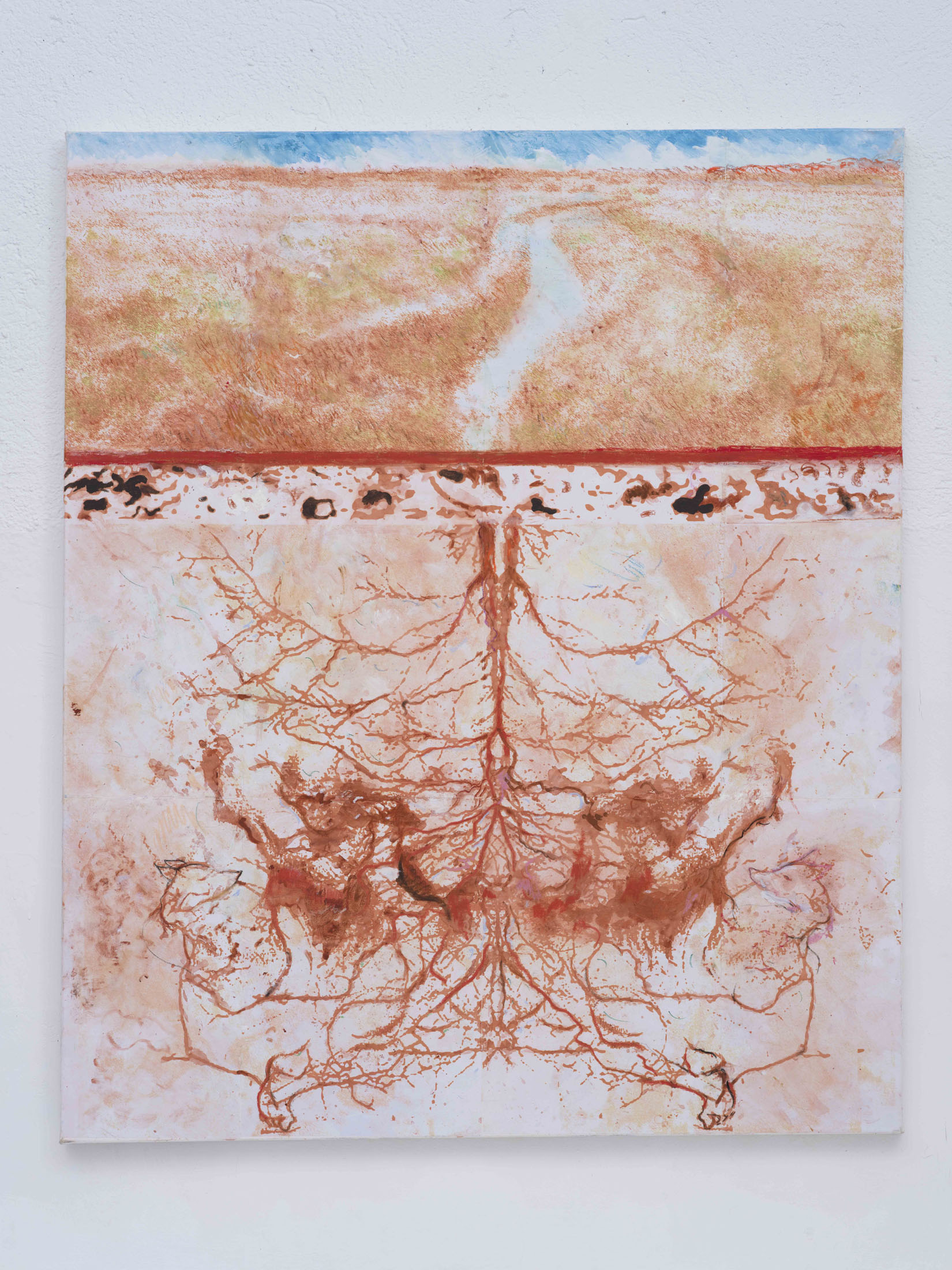

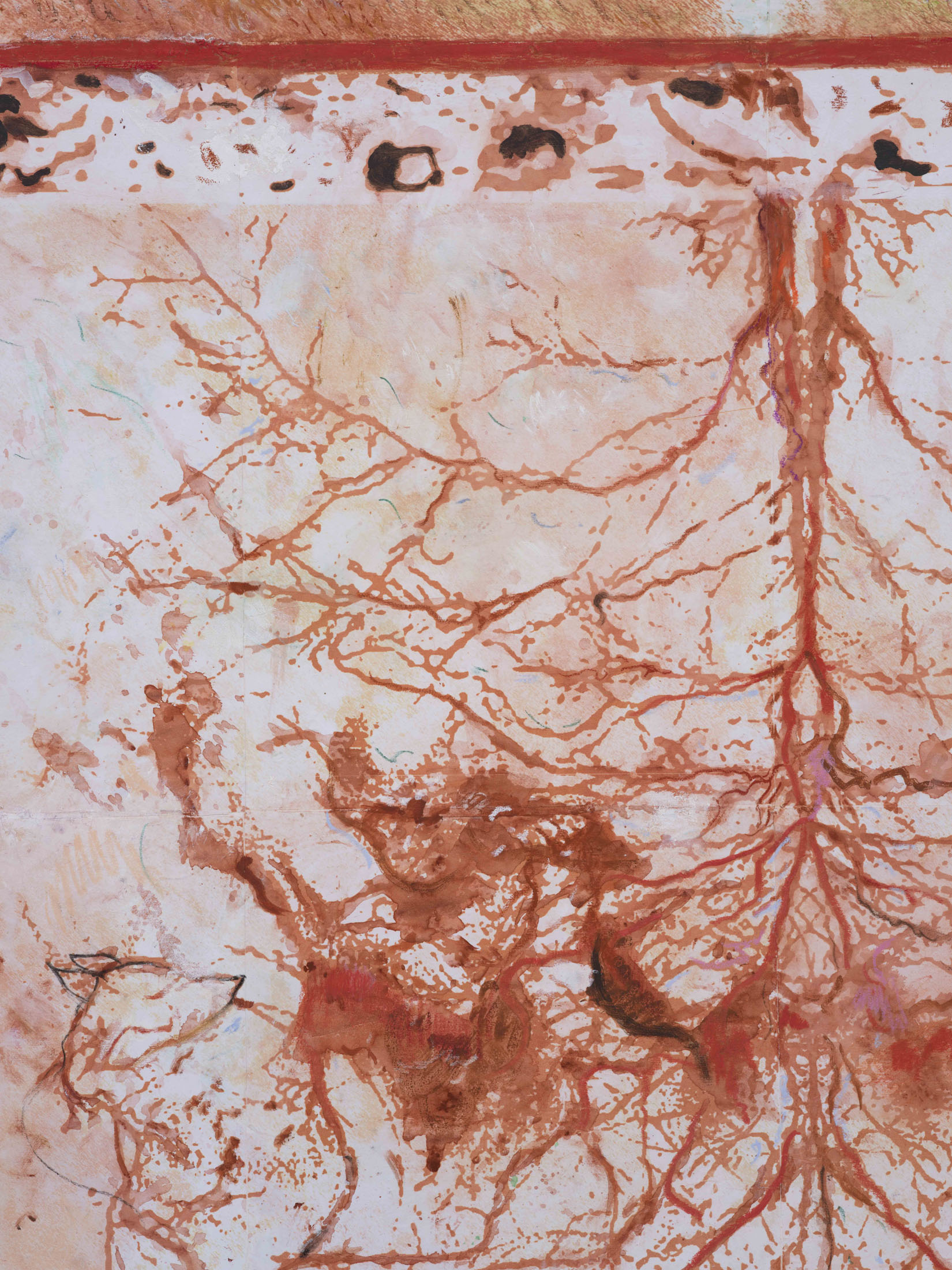

At the heart of the artistic project lies a profound concern with loss: ecological loss connected to coastal erosion and environmental degradation, personal and collective loss, and a larger mood of transience. However, the presence of loss coexists with – and is integral to – an elemental sense of vitality, which is expressed through an exuberant use of colour. The bright reds are derived from cliff clay and fragments of local bricks from abandoned human settlements in Happisburgh; the vivid greens come from clays and copper residues in Benacre, Suffolk; and the deep blues contain traces of woad dye pigment sourced in Norfolk.

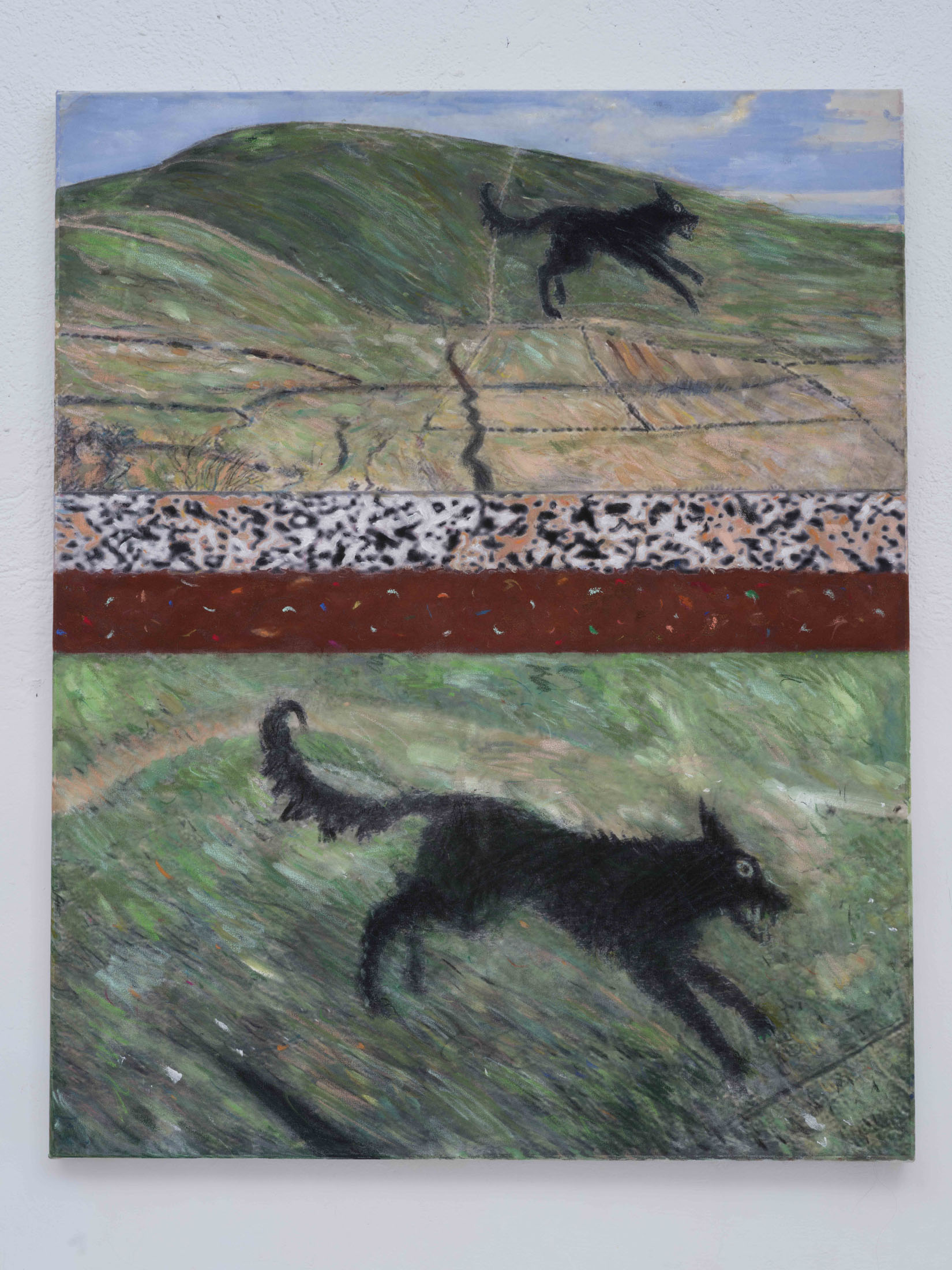

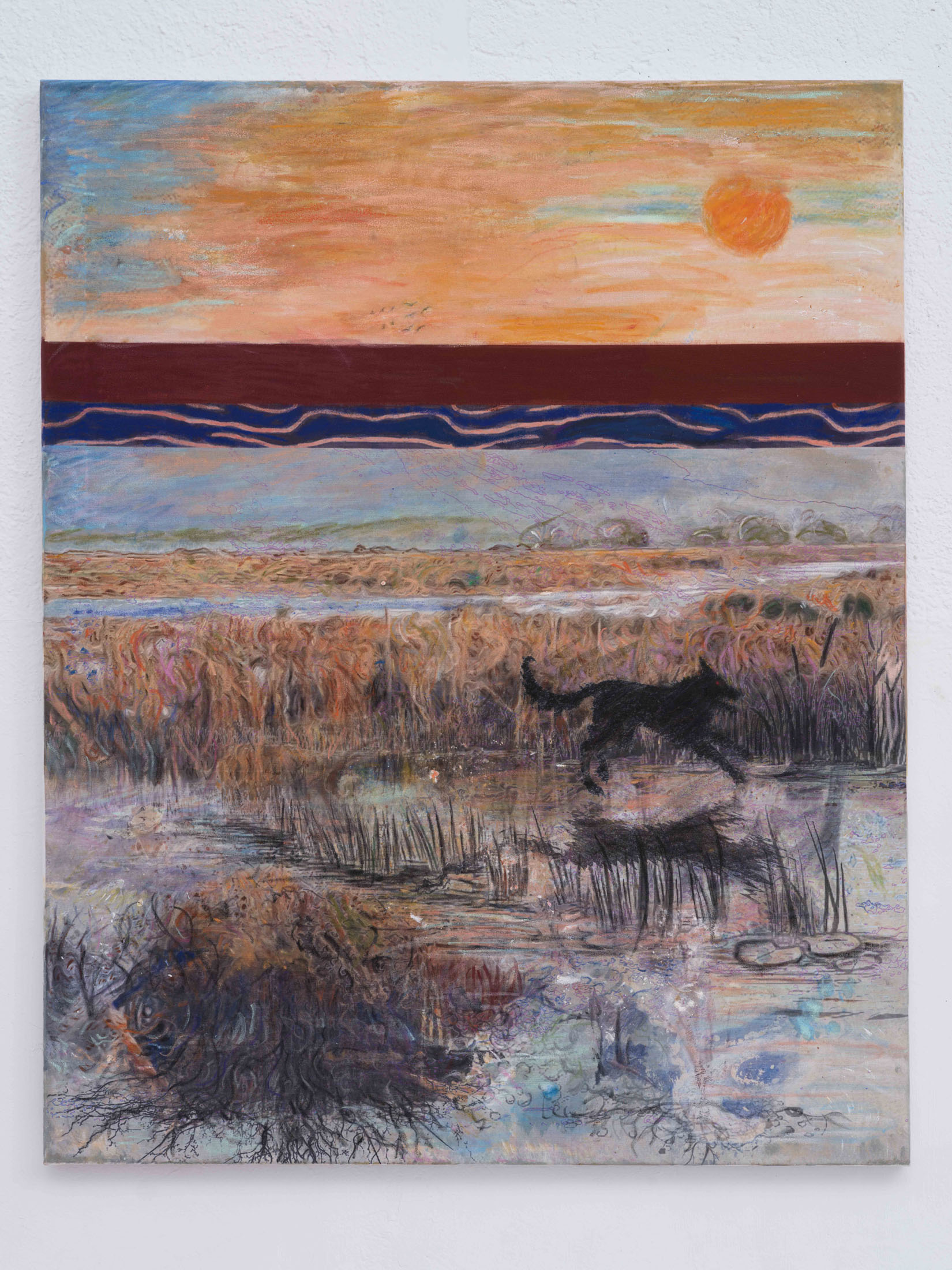

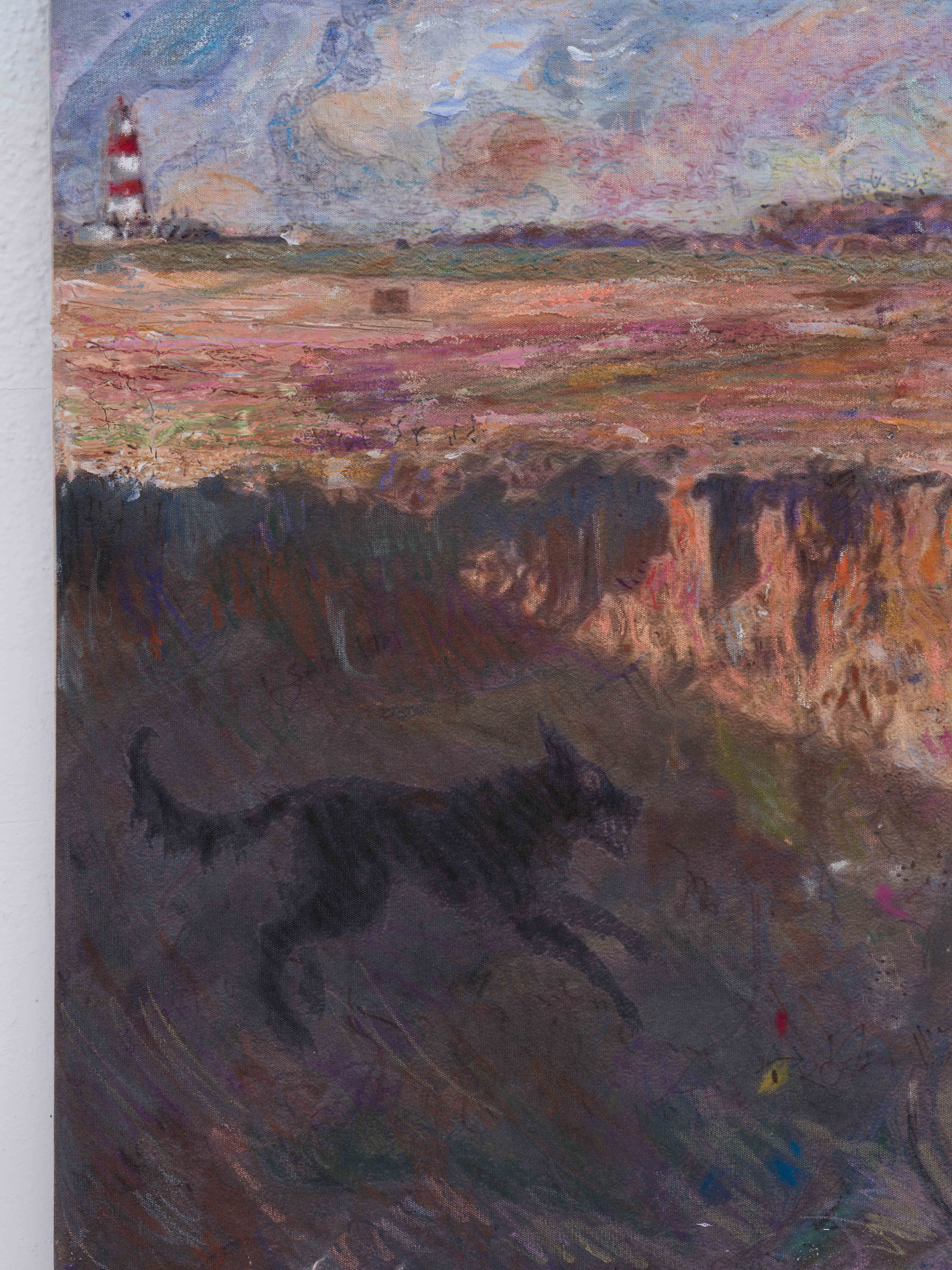

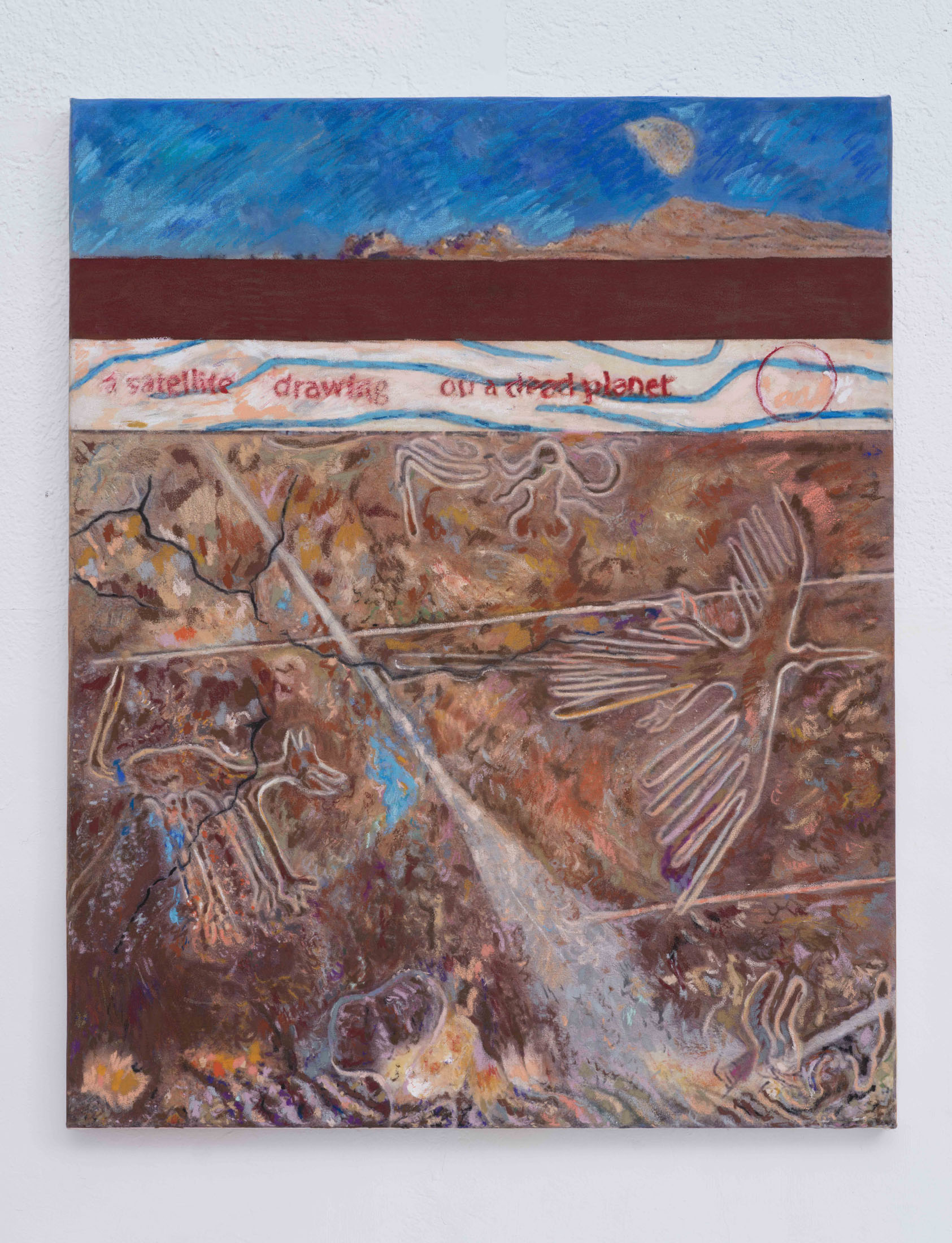

Alongside themes of loss, Mead’s artistic itinerary unfolds through stratification. On the practical level, the idea of stratification is carried out through the incorporation of layers of fragmented risograph screen-prints. Through the layering of meaning and material, stratification enables us to bear witness to the long geological and temporal processes explored in the paintings, as well as their sedimented conceptual and affective strata. The presence of multiple layers invites successive levels of engagement with the images – yet another kind of stratification – and connects to the long, entangled temporalities of human and deep time. The materials Mead uses, gathered from the East Anglian coast, are in themselves a tangible synthesis of past and present and, through their incorporation into the paintings, their life is further extended into the future. Impermanence is thus turned into permanence; what has been discarded, eroded, forgotten, consumed, and abandoned is repurposed as artistic material. As such, this approach exposes various modes of persistence of the past into the present and the future, and their impacts on human and non-human life. For instance, “Orford Shadows” depicts remnants of nuclear site infrastructure in Orford Ness that will mark the scenery of the Suffolk coast for many years to come.

The non-human is embodied by the Black Shuck, a figure of East Anglian folklore akin to a dark, stray dog. The presence of the Black Shuck is simultaneously chthonic and somewhat playful; roaming across the collection, disappearing and re-appearing, the dog wanders through time and space and moves between the earthly world and the underworld. Its intermittent presence invites the viewer to join the time-travel inspired by the paintings.

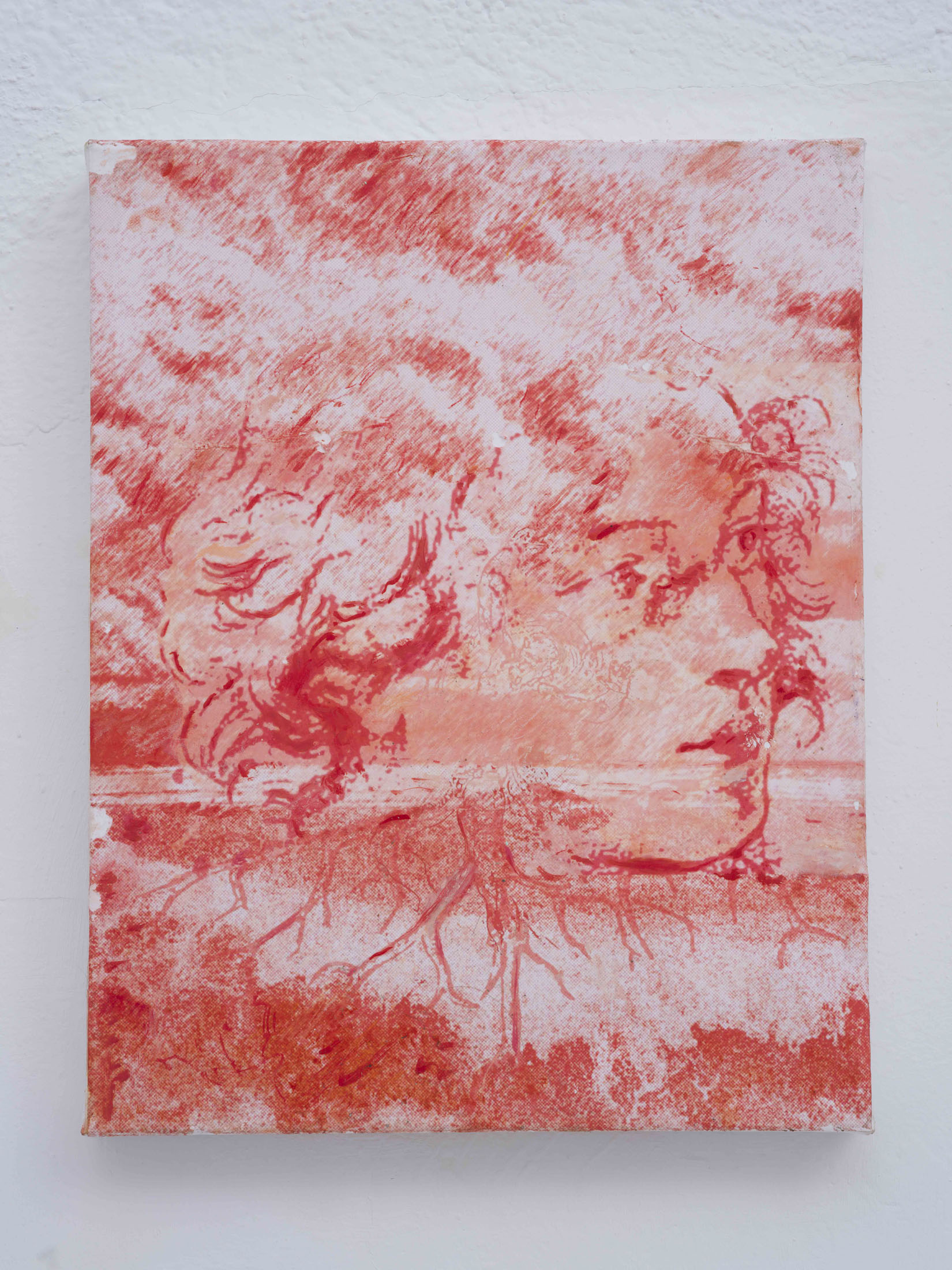

The human body is also layered and absorbed into the natural landscape: limbs like branches, veins like streams, curls like clouds, silhouettes of human shadows pooling like water or carved like caves. The confines between lands and bodies are blurry: they permeate through life and in death, and the reuse of materials derived from the natural environment reproduces this entanglement in the paintings, both practically and figuratively. For instance, in “Above the Distant Shore” human figures appear to descend underground, immersed in red earth that acquires a quasi-liquid quality, reminiscent of an ancient seabed. Conversely, in “Ghosts on the Surface”, spectral revenants seem to rise from the clay that bears their fossilised imprints. What emerges is a powerful sense of unity and coherence: amidst fractured environments and disjointed temporalities, Mead traces a path towards a renewed sense of cohesion, attuned to both environmental precarity and human vulnerability.

The collection also offers a timely reflection on the environmental crisis more broadly: what eludes our understanding, is invisible or temporally displaced, nevertheless still pervades reality and even becomes part of its very substance. In Mead’s art, that which is often unseen or elusive becomes visible, present, and almost tactile. Similarly, the intensity of the colour infuses the paintings with a sense of transformative defamiliarisation: familiar landscapes are turned into vibrant figurations of the convergence of different temporal planes and different forms of existence. They show us that, every time a world is lost, another one is made anew.

–Silvia Vittonatto

[1] I borrow this conceptualisation of spectrality from Bob Plant’s “Living Posthumously: From Anticipatory Grief to Self-Mourning.” Mortality, vol. 27, no. 1, 2022, pp. 38–52.