Artist: Rebekka Benzenberg

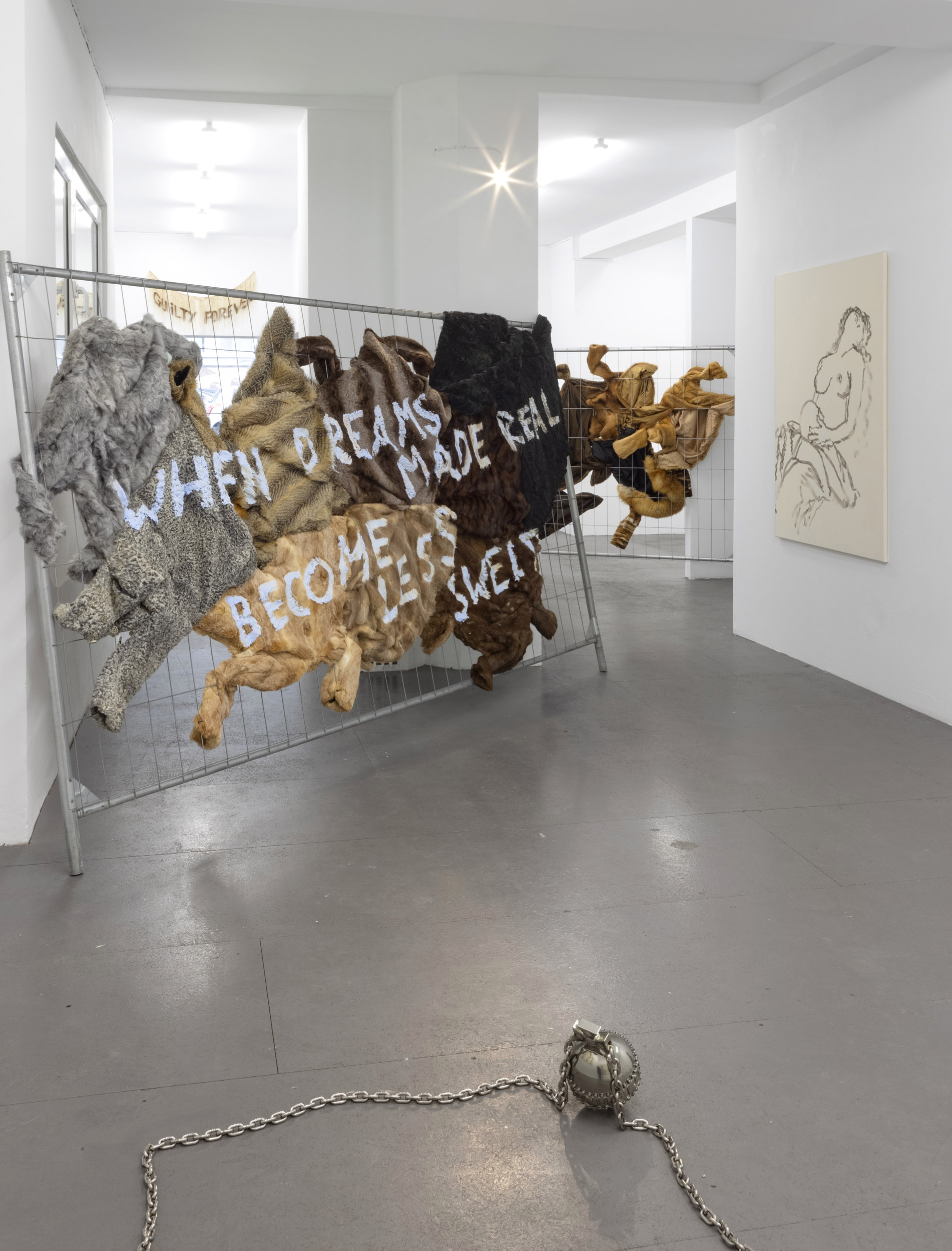

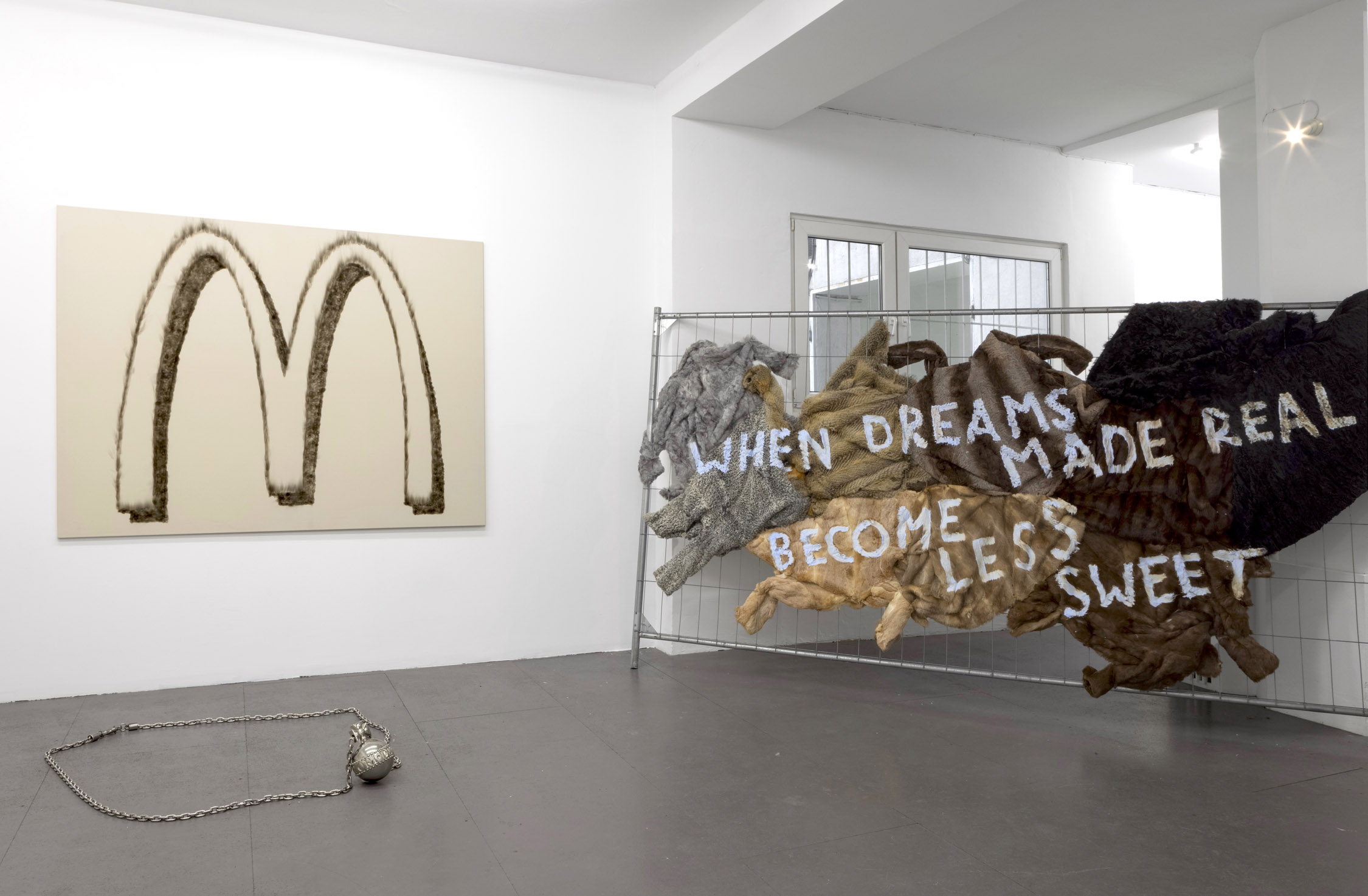

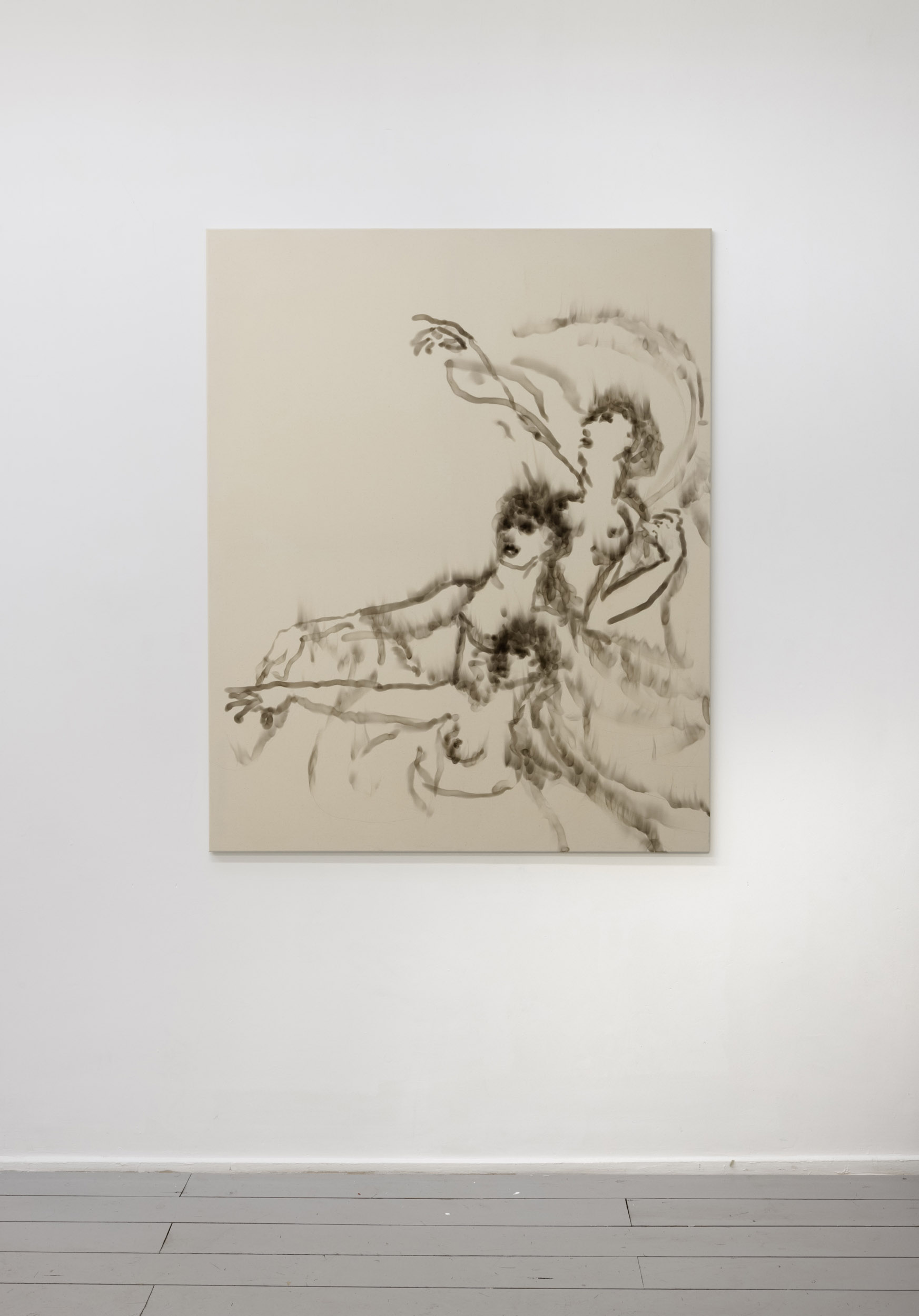

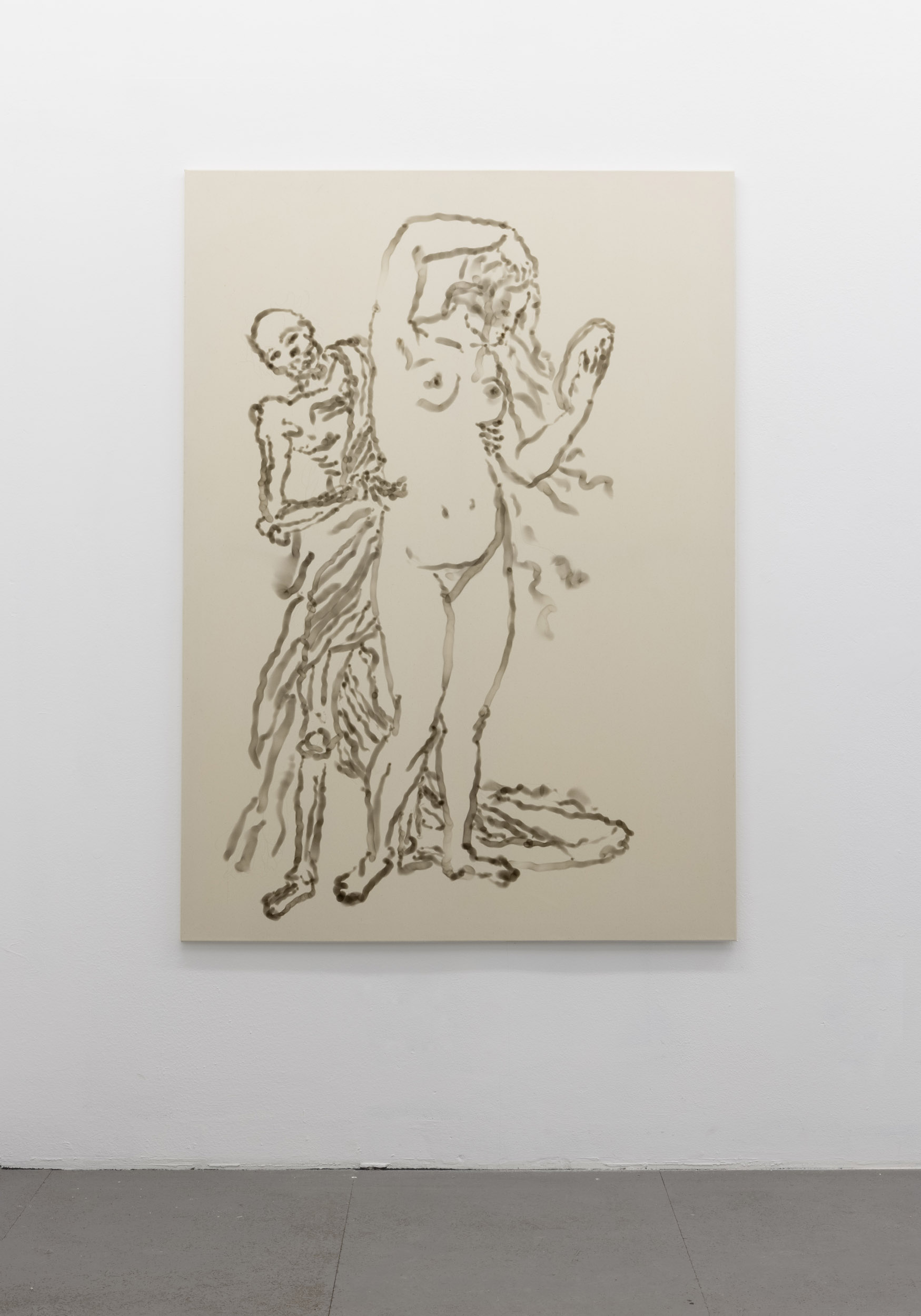

Exhibition title: You know my method – Take a chance

Venue: MARTINETZ, Cologne, Germany

Date: March 3 – April 27, 2024

Photography: ©Tamara Lorenz / Courtesy the artist and MARTINETZ, Cologne

The first day of Umberto Eco’s epochal novel The Name of the Rose begins with the journey of the young novice Adson von Melk to a Benedictine abbey in the Ligurian Apennines in late November 1327. In his role as an aide-de-camp to William of Baskerville (!), he accompanies the Franciscan monk to meet a delegation of the Pope. While on route to the abbey the two travellers hike through the snow and encounter a group of excitedly gesticulating monks, who are clearly in search of something. Upon greeting them, William demonstrates the acumen of his mind by not only pointing them in the direction of the runaway horse without even having seen it, but by also naming it and describing its appearance. To Adson’s astonished question as to how he could know all this, William replies: “Throughout our journey, I have been teaching you to read the signs with which the world speaks to us like a great book.”

In this passage, Eco is alluding to Voltaire’s famous story Zadig ou la Destinée, which was first published in 1747 and is likewise about the reading of signs and traces. Zadig, like William of Baskerville, describes the appearance of a runaway horse and the queen’s dog without having seen either of them. While Zadig reads the dog’s tracks in the sand, William reads the snow in which the marks of the escaped horse are inscribed.

Eco’s role model for the character of William is, as the surname of his protagonist suggests, Conan Doyle’s renowned detective Sherlock Holmes, who in the third novel of the series is confronted with the eponymous Hound of the Baskervilles, whose huge footprints are found at the scene of the crime.

In the deciphering of the references, a happy chain of signs unfolds between the individual stories and figures for the reader along the interpretative action of reading traces. And it is precisely here – in the reading and interpretation of signs – that Rebekka Benzenberg’s artistic research and creative practice begins. With a detective’s eye, she focuses on the history of the representation of women in the visual arts or, to put it more pointedly, on the cultural history of misogyny. She explores the transformation of iconic signs and their meaning through the representation of femininity in her works. She stages the shift in meaning of motifs by placing the strongly connoted signs in new historical and social contexts, thus challenging new observations that do not push aside previous interpretations but utilise them as an active potential for generating meaning to allow the revolutionary desire for a reversal of meaning to become visible.

The subject of her works articulates a discourse on power by means of gender-specific signs that deal with the (defamatory) representation and depiction of femininity – for example in Benzenberg’s examination of the witch masks from carnival tradition – while also revealing a form of female empowerment. The female figures sculpted in the urban outdoor space, which the artist then brings into the exhibition space in the form of chrome-plated sculptures held by aluminium frames, question deeply rooted fantasies of power by showing that the forms of female representation, which are mostly designed by the male gaze, are mostly simplified and distorted to a few mythological or biblical roles – Mary, Flora, Mermaid, Fortuna…. By concentrating on female characters and moulding only them, even if the sculpture includes other people or elements, she addresses a simultaneous decision-making process. Firstly, she emphasises the dominant male perspective on the representation of women in social urban contexts, which substantiates a manipulation of the view of the female body in the monuments. Then, in a second step, her decision to mould the female figure alone and to re-stage it accordingly draws attention to the urgency of gender equality and individual empowerment in today’s society.

This is how the relationship between iconic signs and historical context, which is always subject to change, becomes visible. ‘Venus at her Mirror’ (‘La Venus del Espejo’ / or later the ‘Rokeby Venus’) by Diego Velazquez from 1647 – 1651 is an example of such an iconically charged sign and a motif of Rebekka Benzenberg’s soot or fire drawings. Velazquez presents the mythological figure naked, stretched out with her back to the viewer. In 1914, she became the target of an attack when the women’s rights activist Mary Richardson demonstrated against the arrest of the British feminist theorist and suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst and deliberately sought to destroy the ‘most beautiful woman in mythological history’ in order to draw attention to the fight for women’s suffrage and the emancipation of women. In 2023, the painting was attacked by climate activists who, in their action, explicitly referred to the 1914 attack. In addition to the soot/fire drawings, which allude to forms of expression such as those found in the toilets of clubs or bars, the image of Venus also appears in the artist’s oeuvre as a patch design on the oversized denim jacket resting on an oversized high chair frame. Consisting of many individual jackets sewn together, the patches are an expression of an attitude and the representation of belonging to a group or organisation, thus manifesting being part of a movement. The image of Venus therefore migrates from a mythological representation to a target of protest for women’s rights or climate policy to the expression of a political statement.

Rebekka Benzenberg not only examines the shift in meaning in the subject matter of her works, but also focuses on transformation in her choice of materiality. From fur’s original protective function to the staging of fur as a symbol of (royal) power, the material is already undergoing transformations of meaning in our cultural world, transformations we also consider when viewing it. The same applies to the associations of fur as an erotically charged item of clothing worn by women and the animal rights protest movements. In this way, different levels of meaning collide with each other, almost symbolically, when mounted on a building fence, and challenge us as viewers. As a result, the material, as well as the subject matter, undergoes a radical reinterpretation that takes the viewer well beyond the normal paths. The ‘sign’ fur, which must be interpreted or read, evokes several stories in our viewing perspective, which can lead to unsettling changes and deviations in its meaning, to the point of complete inversion of the content.

Rebekka Benzenberg’s method manifests itself in the artistic tracing and shaping of these significant signs. Across her diverse works, she repeatedly seeks out motifs and expressions of misogyny, which she then not only makes visible, but also transforms. The viewers who “read” the works are confronted with visual codes whose validity is confirmed by the society that uses them. As such, questions concerning the representation of female bodies in urban contexts and the presence of women in contemporary societies are a question of the respective codes that shape our world and that govern the way in which viewers read it. The exhibition title ‘Take a Chance’ not only refers to a quote from the song ‘What You Waiting For’ by Gwen Stefani, in which she reflects on ageing and the connections between female success and youth, but also invites the viewer to take a chance by interpreting signs independently, to draw ‘investigative’ conclusions and to take action. The signs are inscribed on both bodies and in the space as patches on oversized items of clothing and as banners throughout the room; it is up to us to imbue them with a new, socially transformative meaning. Rebekka Benzenberg’s ‘Take a Chance’ is reason enough to do so.

-Stefanie Kreuzer