For Condo London, Public Gallery is pleased to present Grid Systems, a solo exhibition by London-based artist and composer Raheel Khan, whose practice spans installation, performance, sound, text and sculpture. Situating the grid as a marker of modernism and systems as a method of critique, the exhibition presents a series of works on panel alongside a site-specific installation, made from reclaimed material sourced from the gallery’s space at 89 Middlesex Street. Khan regards infrastructure as an active field of registration, attending to markers of wear, misalignment and decay as generative conditions through which social and material histories are reconfigured. Across two floors, Grid Systems assesses the deconstruction of formalism and the emergence of systems-based art, taking the history of the brutalist estate and its surrounding neighborhood as a material register for staging this debate.

Grids

In her 1979 essay Grids, Rosalind Krauss claimed that “the grid functions to declare the modernity of modern art … a place that was out of reach of everything that went before. Which is to say, they landed in the present, and everything else was declared to be the past”. The grid, Krauss argues, operates as modernism’s structuring fiction, presenting itself as neutral while in fact functioning as a disciplinary framework that polices meaning and suspends time.

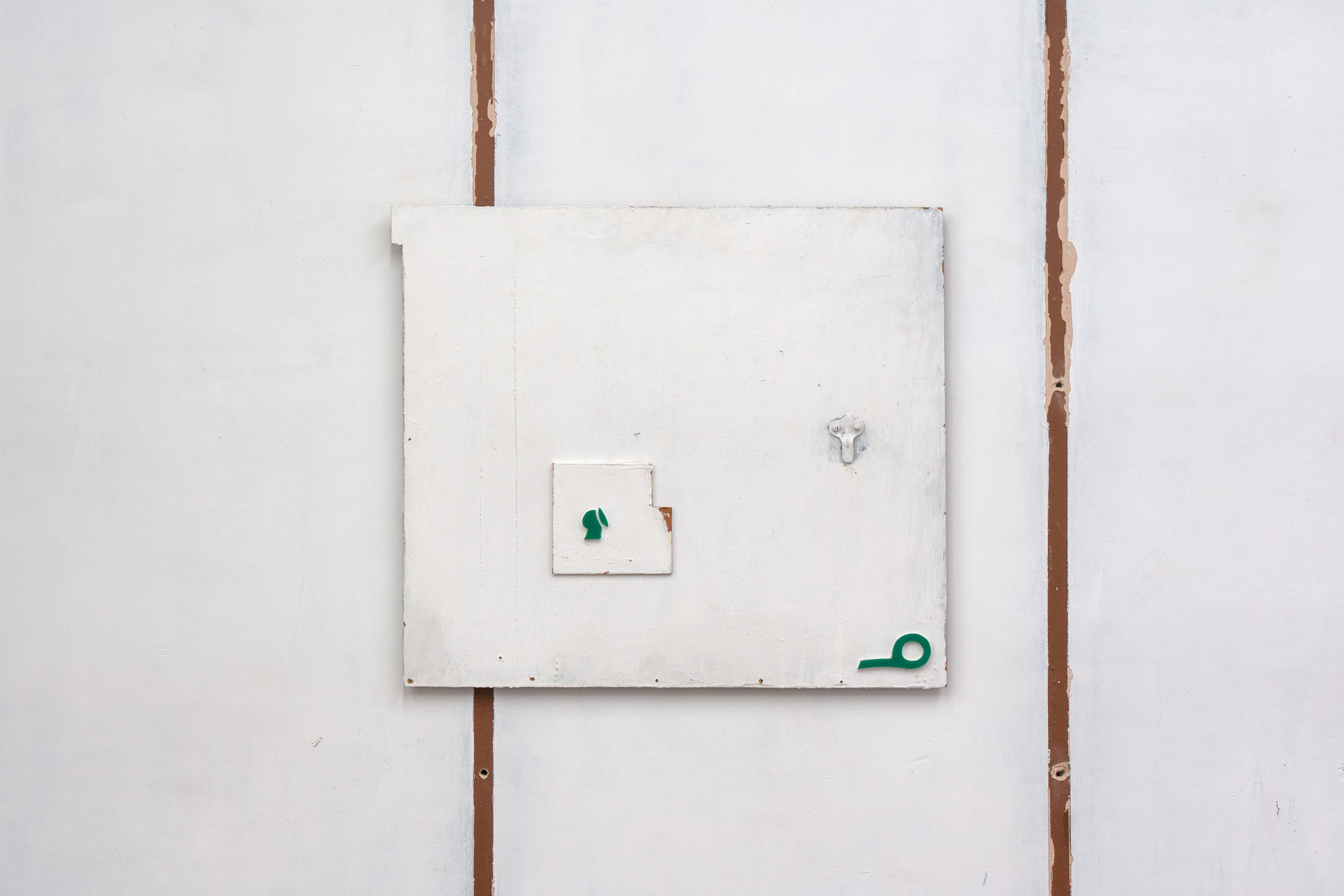

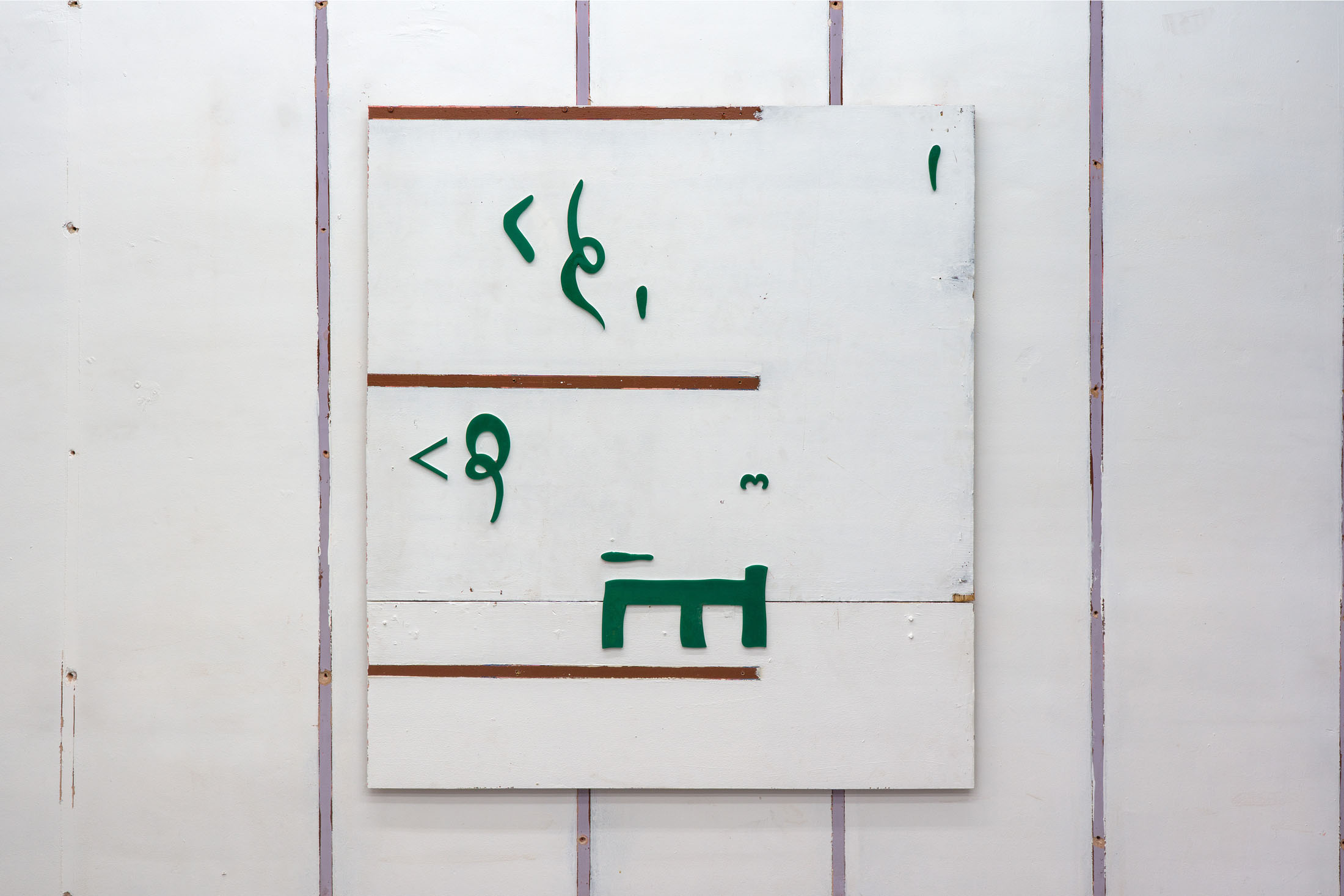

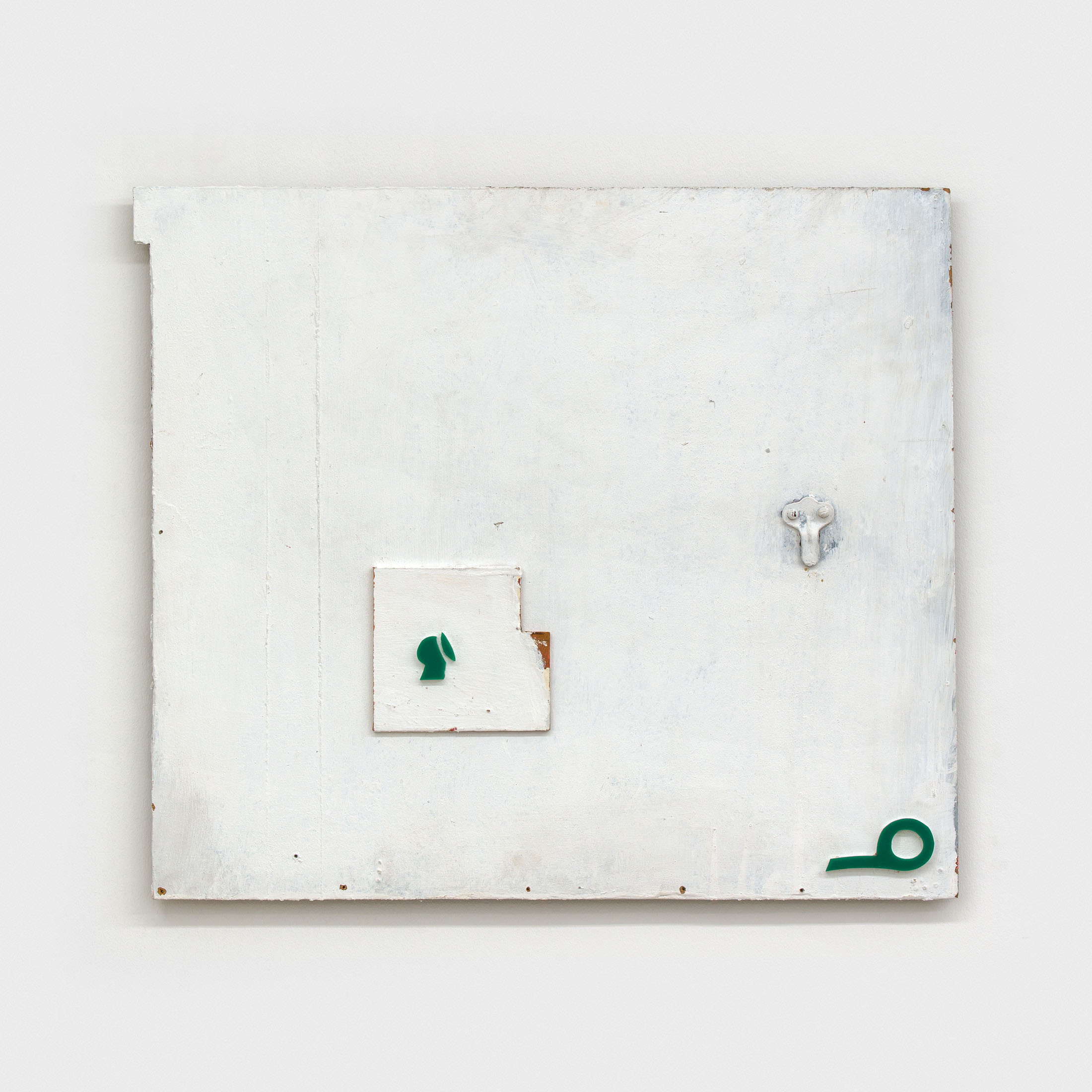

Through the floor tiles, brick bonds and ceiling panels, the grid surfaces in the architecture of the gallery’s ground floor. Absent shelf supports score sites of removal in regular intervals, each leaving a shallow rectangular scar, its edges softened by successive coats of paint. Moving through the space, the viewer encounters a grid that no longer stabilizes the visual field but instead indexes absence and erosion. This is the grid hollowed out: retained as a visual schema while stripped of its capacity to order meaning.

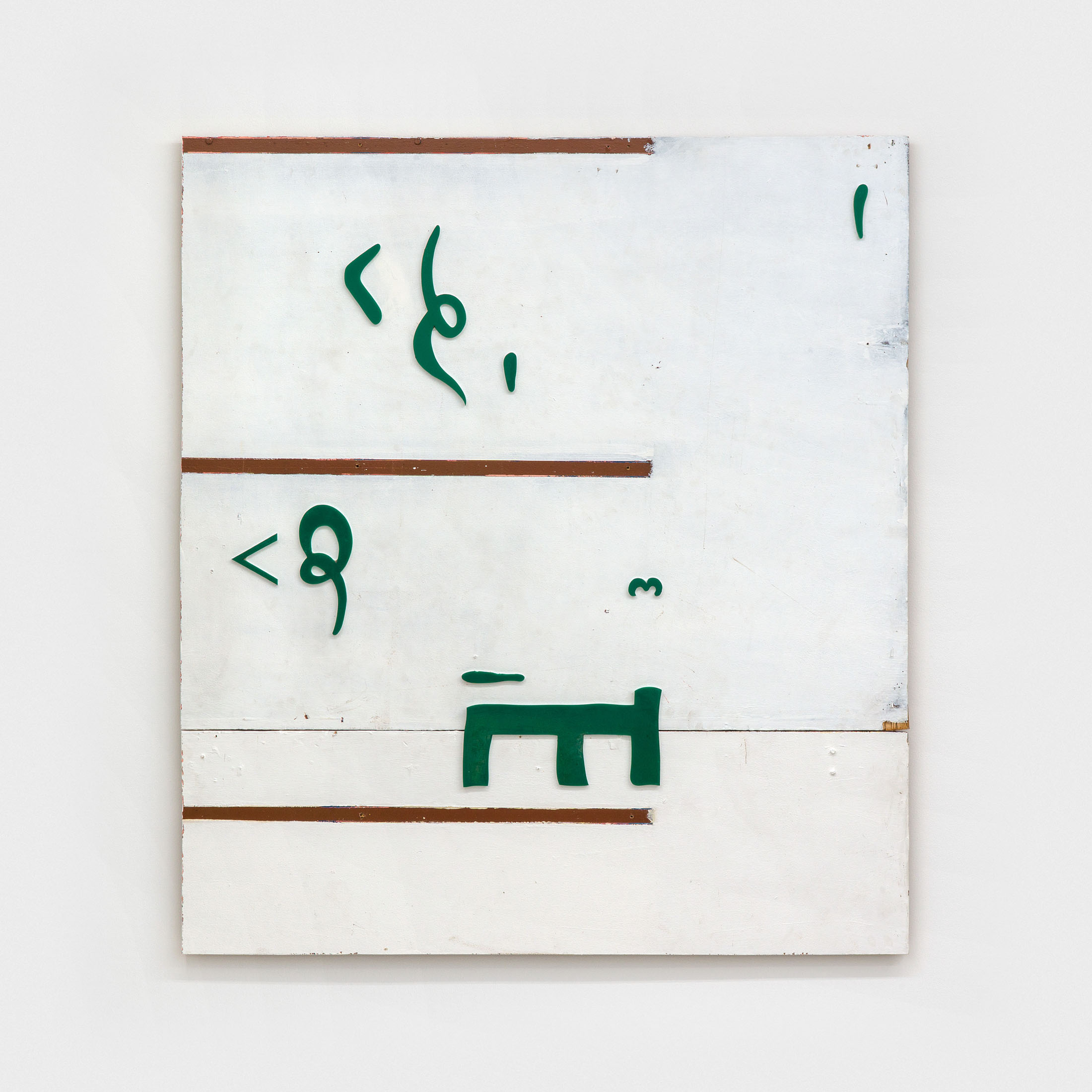

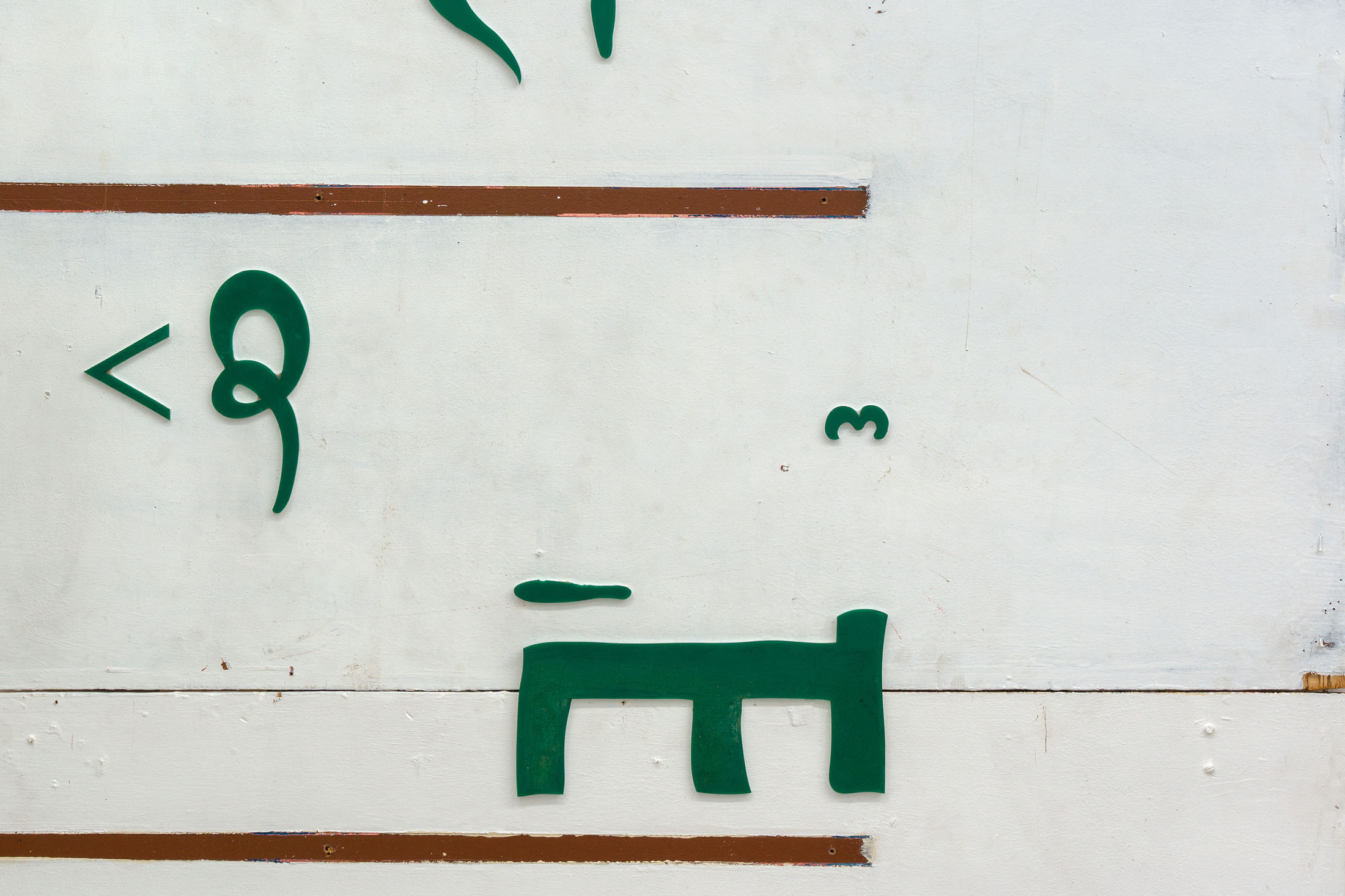

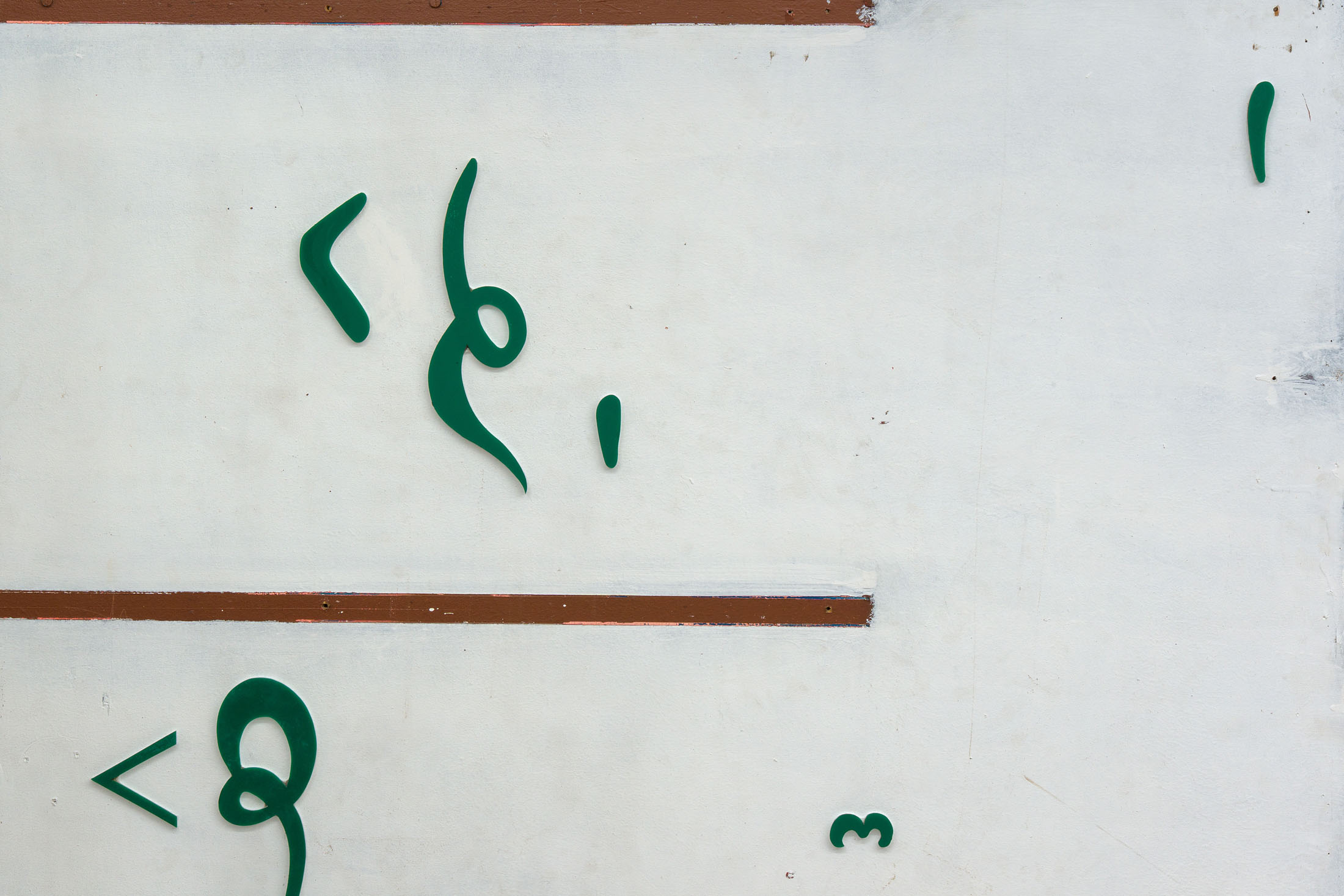

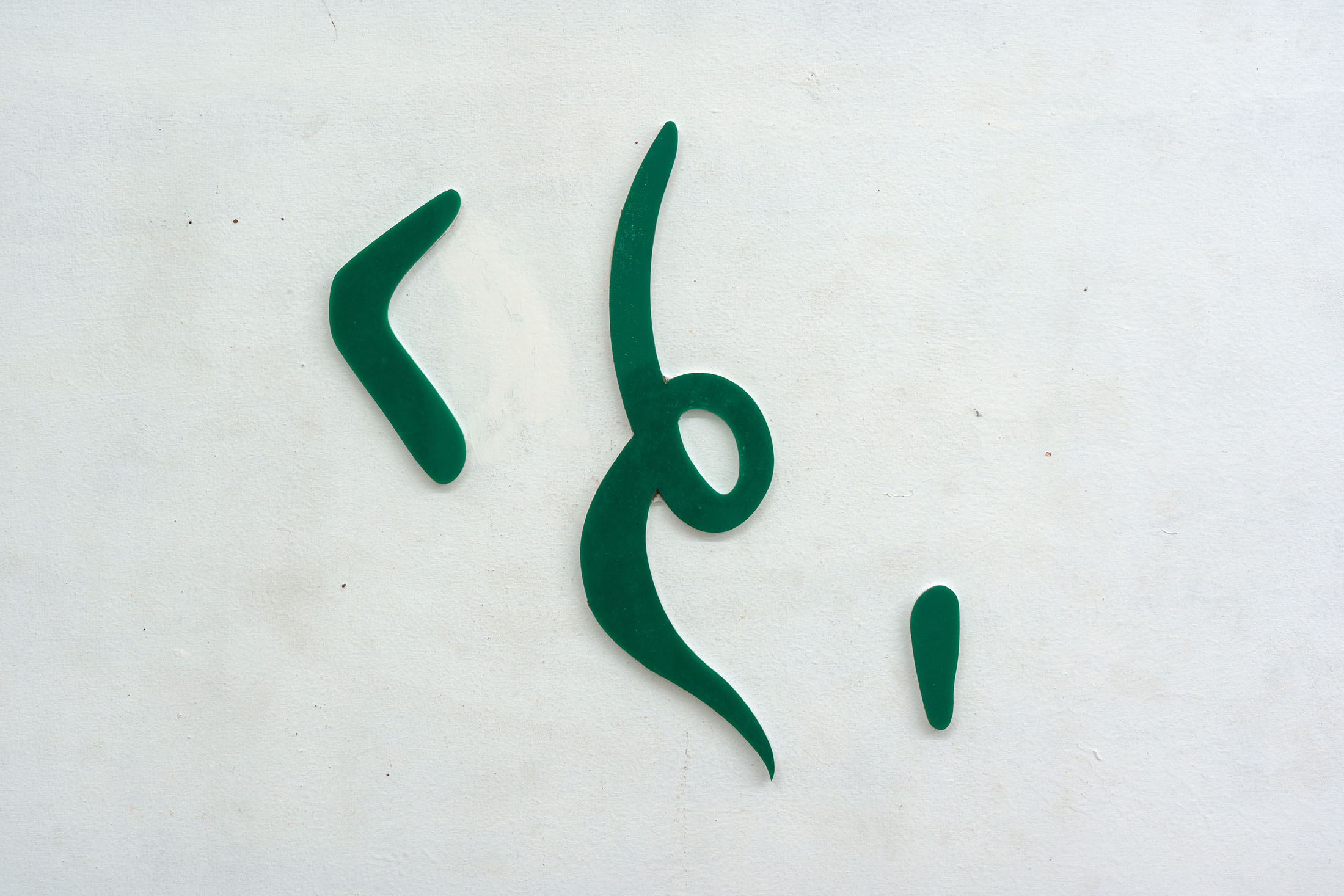

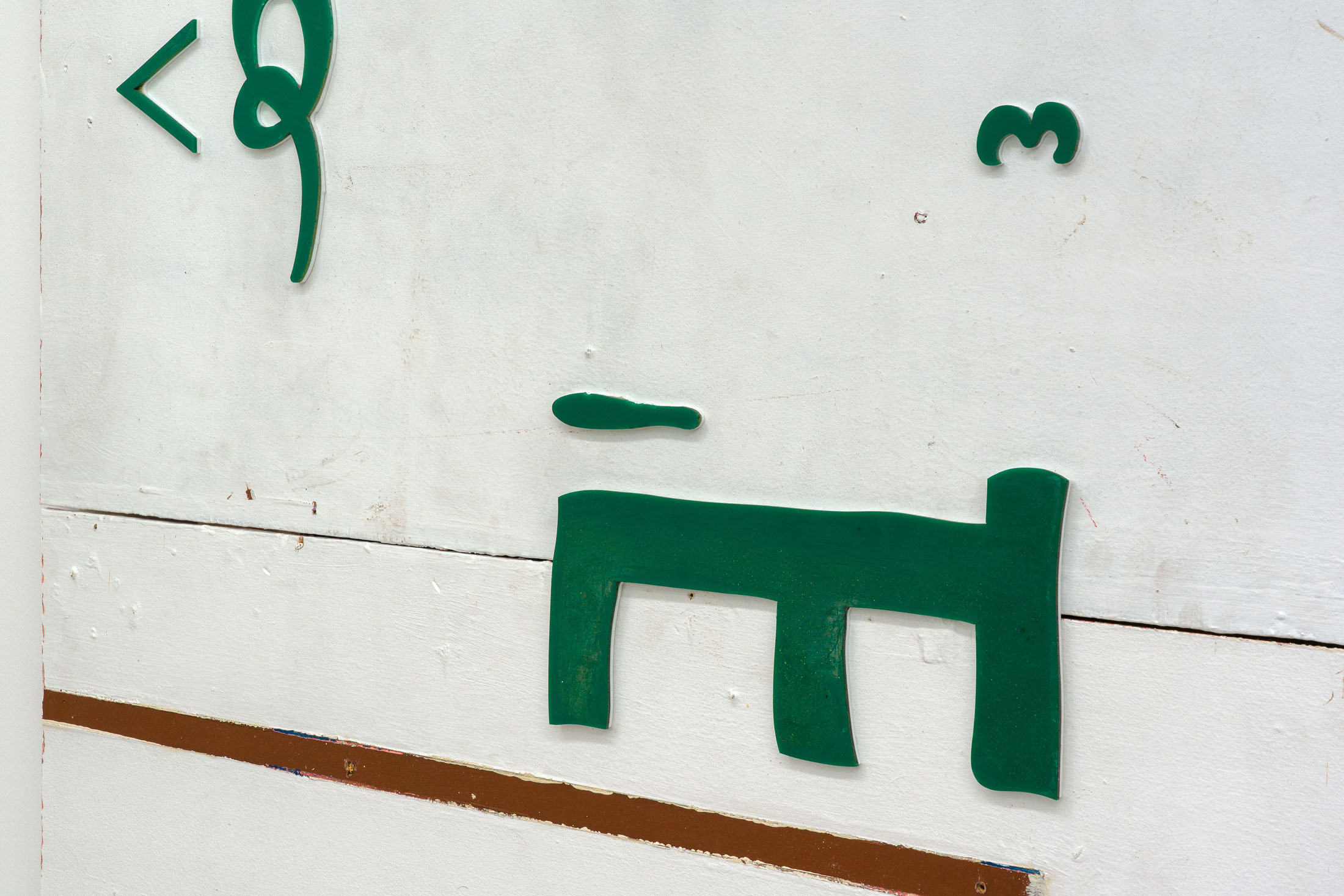

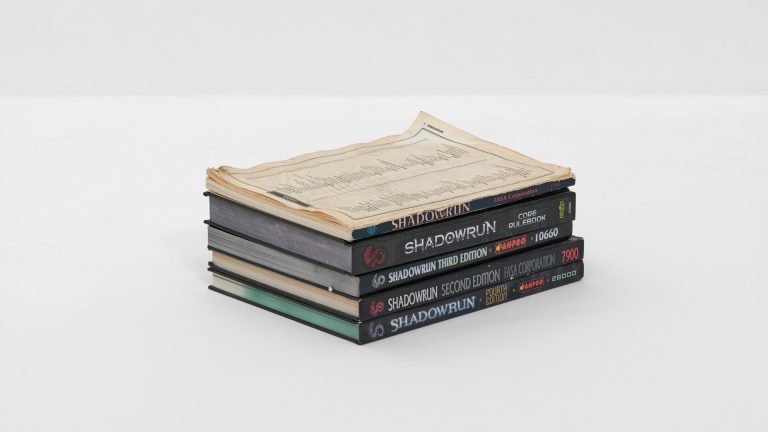

Khan’s wall-based works mobilize composition not as expressions of formal coherence, but as measures of instability. Integrating cut-up shop signs and found materials, they disperse authorial intention – a process of registration rather than expression. The method of deconstruction weighs in similar importance to that which is being taken apart: a gallery space housed in a brutalist estate, erected as a proclamation of utopian progress and aspiration, yet equally marked by a postwar housing crisis in east London, inseparable from the material realities of wartime destruction. Khan’s own familial history echoes this pattern, relocating from Kashmir following the construction of the Mangla Dam in 1966 – its construction mapping a parallel relationship between idealism, industrial achievement, mass displacement and violence. Across his spatial intervention and works on panel, Khan both investigates

the existing infrastructure and deconstructs the apparatus it upholds, situating the grid as a historically embedded framework whose apparent stability depends on a process of erasure.

Systems

Where Krauss’ Grids offers a diagnosis of modernism’s failures in its wake, Jack Burnham is writing on the opposite side of this theoretical threshold, pointing instead to its legacy and naming the conditions that replace it. In his 1968 essay Systems Esthetics, Burnham identifies a paradigmatic transition from an object-oriented culture to one structured by systems, processes and feedback loops. For Burnham, art increasingly functions not as a discrete object but as an operational field embedded within technological, ecological and social networks. His theory emerges from a moment of profound political turbulence, shaped by protests

and sit-ins, riots and high-profile political assassinations, state surveillance, militarization and violent repression. In this context, the system names not an abstract aesthetic category but a nexus of mutually reinforcing structures of domination, from government, organized religion and mass media, to corporate America and Cold War ideology. This historical backdrop is explored in Nervous Systems: Art, Systems, and Politics since the 1960s, in which Johanna Gosse argues that Burnham’s insistence on the plural – systems – signals a dispersal rather than a consolidation of control, “engaging broadly with the complexities and entanglements of global ecologies of information and power”. Bringing Burnham into the contemporary moment, Gosse traces how this nervousness – both informational and affective – forms a line of continuity and thus “retools art for sociopolitical purposes”.

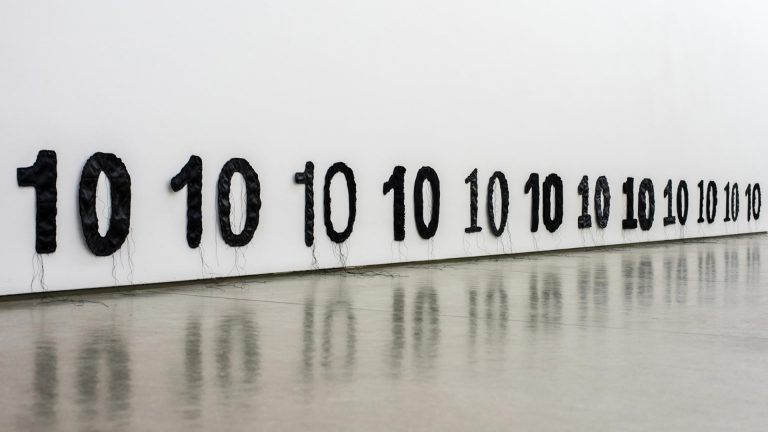

Khan’s installations on the upper floor adopts systems thinking while resisting the rhetoric of dematerialization often associated with conceptual art; he abandons the object without forsaking an engagement with the physical, submerging the listener in a range of embodied and social entanglements through sound, light and sculptural assemblage. A sickly yellow blankets the room in anticipation, unease and paranoia, calling to mind bureaucratic signage or hazard gear. Infrastructural fragments and broken shelf supports constitute an environment that is operational rather than representational. Sound functions as a primary medium through which systems become perceptible, mapping the space acoustically in cyclical chorus.

Siren IV (2026), a four-channel sound installation, articulates these concerns with particular intensity. Playing through tannoy speakers in condensed micro-loops, six voices gradually fall in and out of alignment. The work invokes the aesthetics of civil defense and emergency signaling, while simultaneously echoing calls to devotional address. Its porousness undermines spatial containment, implicating the listener within a field shaped by a continuous state of emergency across several global conflicts, coupled with a shifting political climate in the UK and an impending ecological crisis. The misalignment of the four voices generates a sensation of temporal slippage; sound and infrastructure materialize the links that join the archival, process-oriented, and labor-intensive, the informational and social. It is not a composition but a set of conditions, embedded in networks and existing as a dynamic field of interaction.

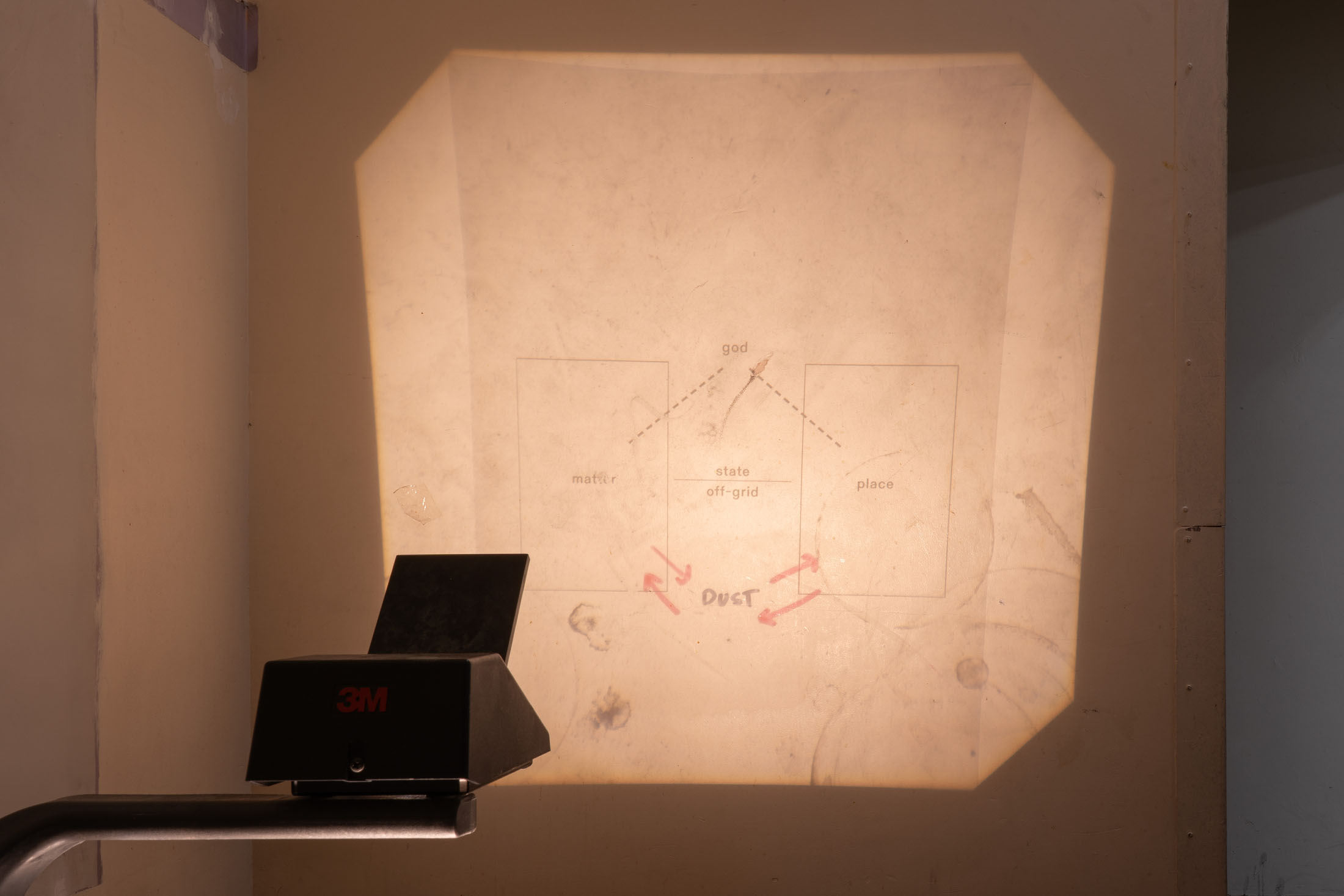

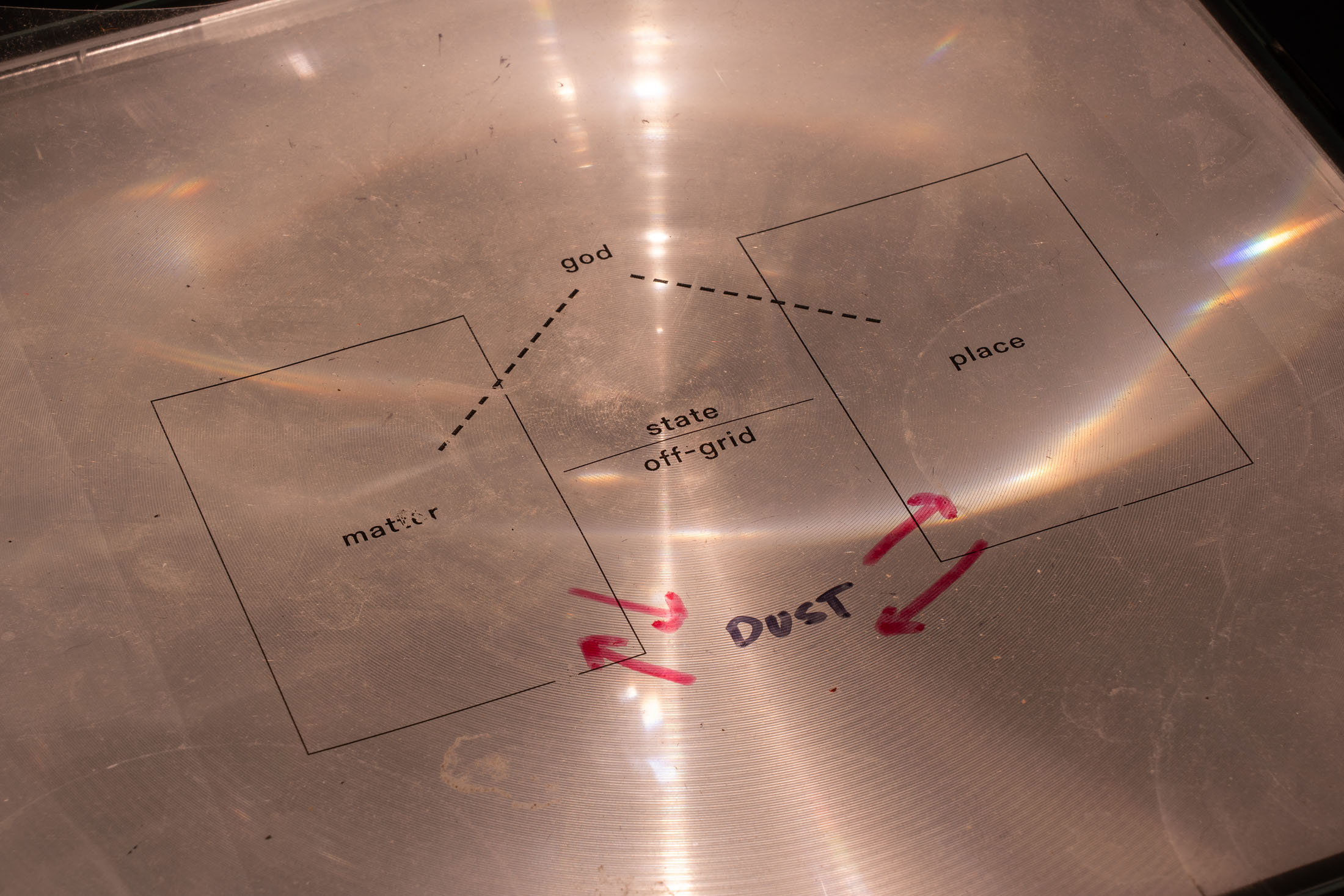

At the base of the stairwell, a projector echoes this networked logic. Surrounded by detritus within the deconstructed space, the projector reads not as a neutral viewing apparatus but as a working technology; popularized in the late 1940s for use in education, business, and military training, the projector carries with it a history of didactic authority and visual control. Here, it sits in marked contrast to the instability of the space it occupies, its continued operation underscoring a tension between function and obsolescence. The projected diagram introduces a theological register that the visual field pointedly fails to stabilize; religious language persists as a cultural force, yet its capacity to organize meaning has collapsed. It situates dust at the base, while divine authority sanctions the state above, holding matter and place in a vertical tension. Yet this hierarchy does not resolve into coherence. Instead, the diagram stages belief as a system whose organizing force persists culturally even as its visual and ideological foundations have eroded. Religious language remains operative, but no longer orders the field with certainty.

Dust

Binding both floors together is dust: abject, liminal and bodily, a trace of mortality and displacement, what moves between matter and place. Dust is an index of the past, produced

by contact, erosion and decay, bearing direct physical relation to what it signifies. This logic situates the exhibition in dialogue with Robert Smithson’s concept of the non-site. Developed at the moment when the grid began to lose its stabilizing authority, Smithson’s non-sites establish a dialectic between a physical place and its representation. Composed of displaced materials, maps and photographic documentation, non-sites are functioning systems.

Grid Systems activates the building itself as a material and historical system, incorporating its architectural features into the logic of the works. Khan’s wall-based works can be read through Smithson as maps or registers rather than images. Dust not only binds the work to a place in the past, but also to the people who occupied it. In his research, Khan understood the surrounding neighbourhood to be shaped by successive waves of migration, from seventeenth-century Huguenots to nineteenth-century Ashkenazi Jewish communities to contemporary Bengali Muslim populations. This history does not reside in the objects or sculptural assemblage but emerges through a feedback loop between the physical materials and the viewer’s conceptual reconstruction of an absent landscape, a terrain made audible by Khan’s sound installation and through which histories of migration, labour, settlement and displacement are rendered legible.

Raheel Khan (b. 1992, Nottingham) lives and works in London, UK. Recent solo and two person exhibitions include Memory Police, Goldsmiths CCA, London (2025); A Public Safety Concern (with Tiffany Wellington), Lisson Gallery & Bomb Factory Art Foundation, London (2024); Compressions, Longsight Art Space, Manchester (2024); and Hum Drum, Deptford X, London (2023). He has participated in group exhibitions at Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham; Bold Tendencies, London; Palmer Gallery, London; Ovada, Oxford; and FACT, Liverpool. His work has been the subject of performances at institutions including Camden Art Centre, London; Whitechapel Gallery, London; Auto Italia, London; South London Gallery, London; Goldsmiths CCA, London; and Southbank Centre, London. Forthcoming projects include performances at Somerset House, London; the Magnetic 4 Residency, Bétonsalon and Fluxus Art Projects, Paris; and the East Gallery Fellowship, Norwich University of the Arts, Norwich.