This text does not aim to clarify the exhibition at hand, nor does it seek to mimic the stereotypical anxieties of a curator struggling with history. Rather, it should be read as a personal confession, with the exhibition acting as a physical support for the ideas explored here. What directly interests me is the question of how Radu Pandele’s art positions itself on the map of contemporary painting. Where can this kind of visual approach be situated, and how does the map itself shift with the appearance of this mode of working?

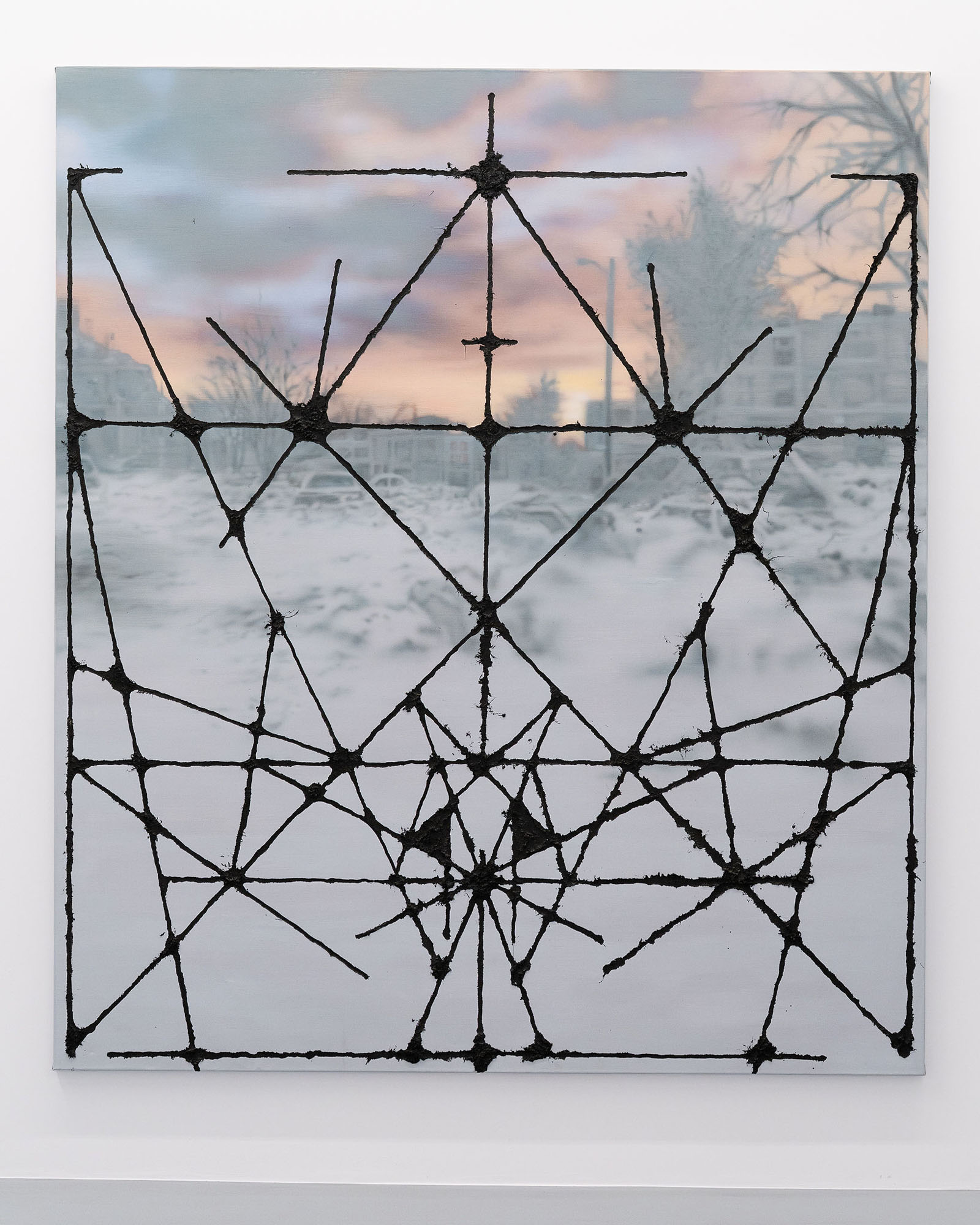

Ironically, painting has died at least five times over the past 500 years — and has returned just as often in various forms and reincarnations. Much to the dismay of enthusiasts of hyper-super-ultra-contemporary art — for whom painting is a defunct phenomenon — this exhibition is an exercise in directing focused attention on one particular aspect of Radu Pandele’s practice: his wall-based works. Volumetric objects and installations have been deliberately excluded, in order to reduce the discussion, with a kind of rigor and austerity, to painting alone. And this discussion unfolds along two lines: what Radu Pandele’s painting looks like at this point in his career, and how the broader landscape of local Romanian painting has evolved in light of this approach.

For those who believe that history — and art history in particular — is a construct made up of revolutions and ruptures with tradition, this exhibition may seem like a retrospective gesture. Yet, in contrast to that narrative, often echoed in the post-postmodern discourse and naively perpetuated in the inflationary language of curating, this exhibition is instead a micro-exercise in questioning how painting — understood as a permanent and recurrent anthropotechnical visual phenomenon — enters into dialogue with innovation and new imaging technologies in our time.

Behind a camouflage that might be mistaken for a solo show, Radu Pandele’s art is brought to the foreground as both a critical and aesthetic reflection on the permeability and resilience of painting in the face of today’s major challenges in the visual arts.

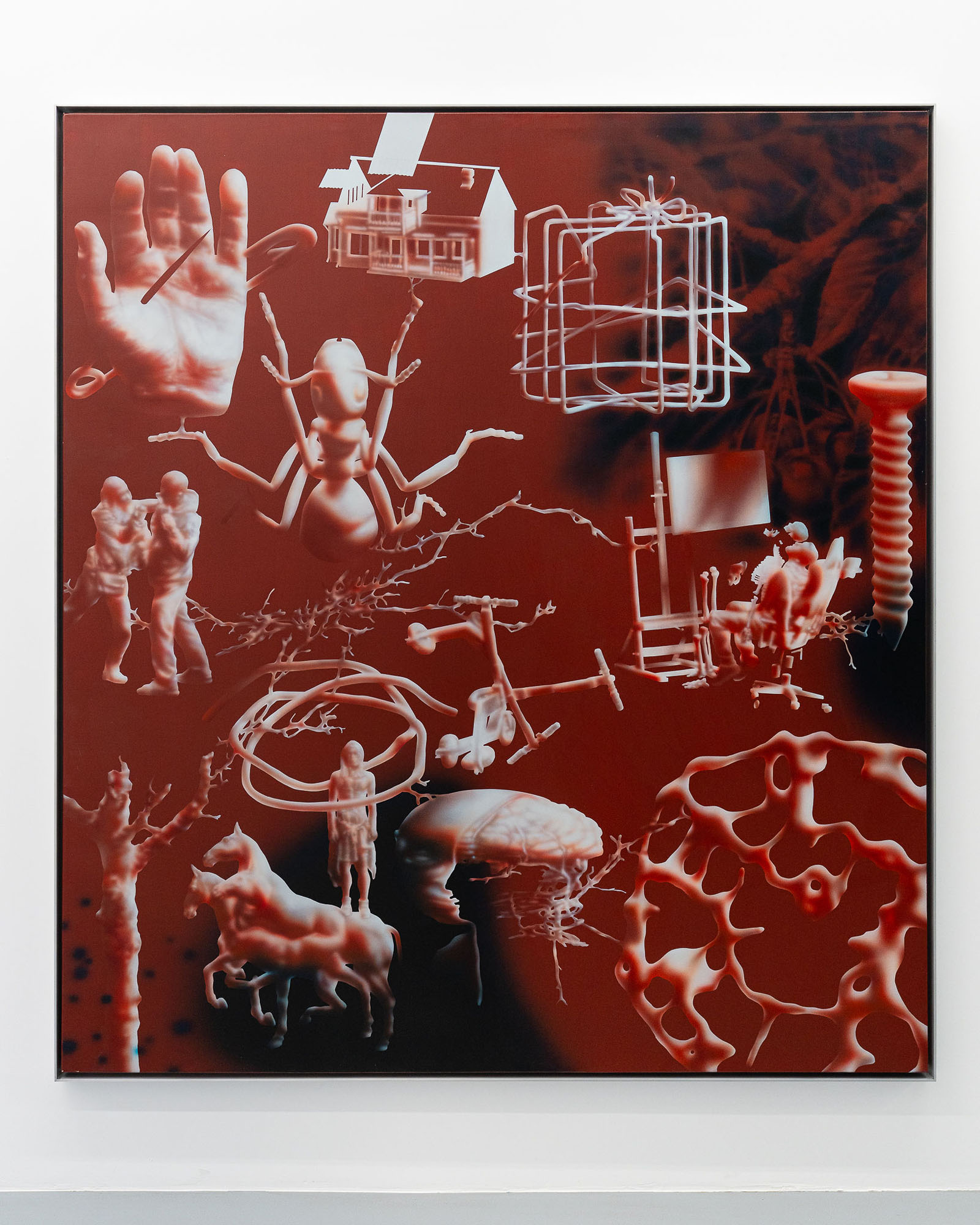

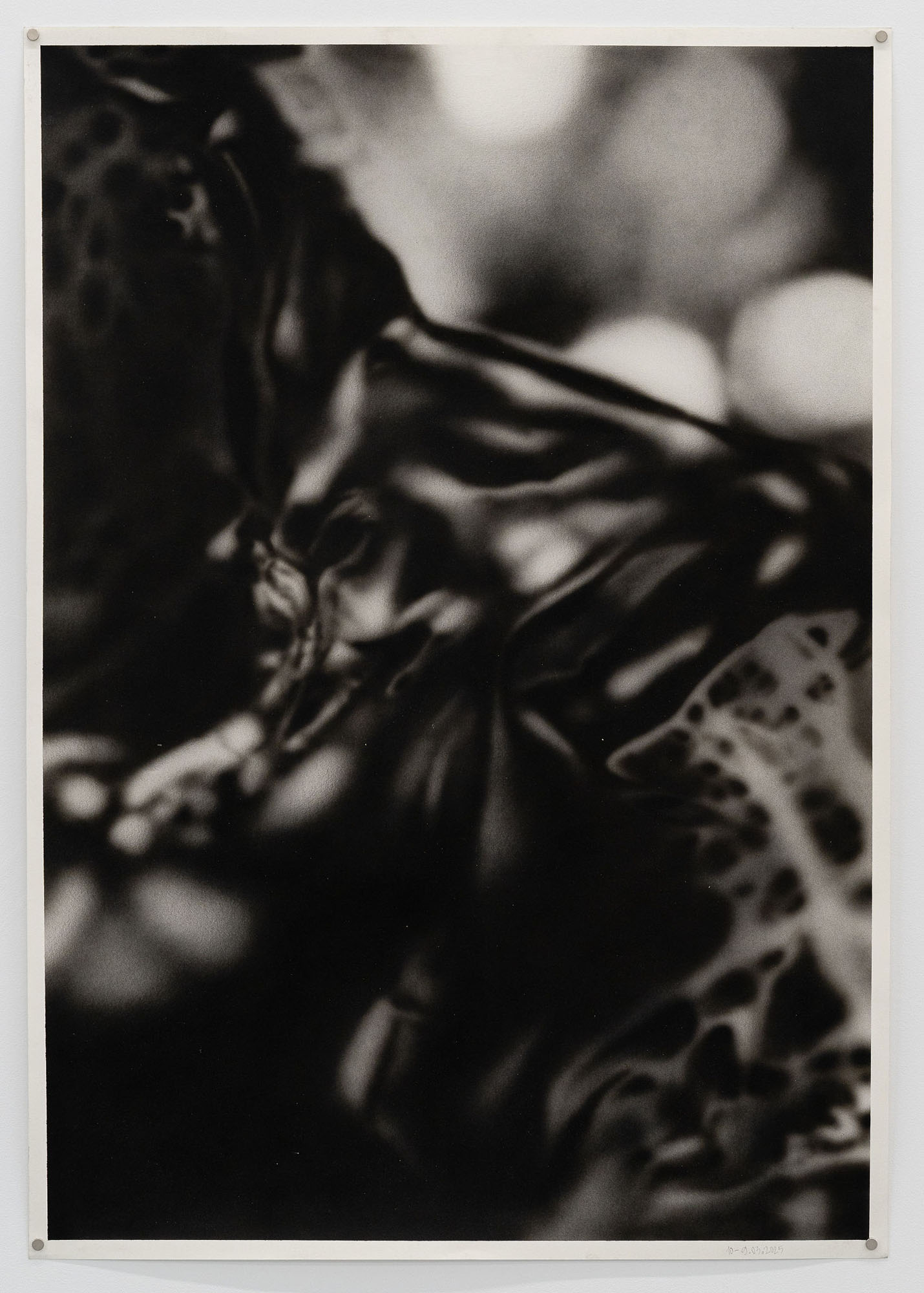

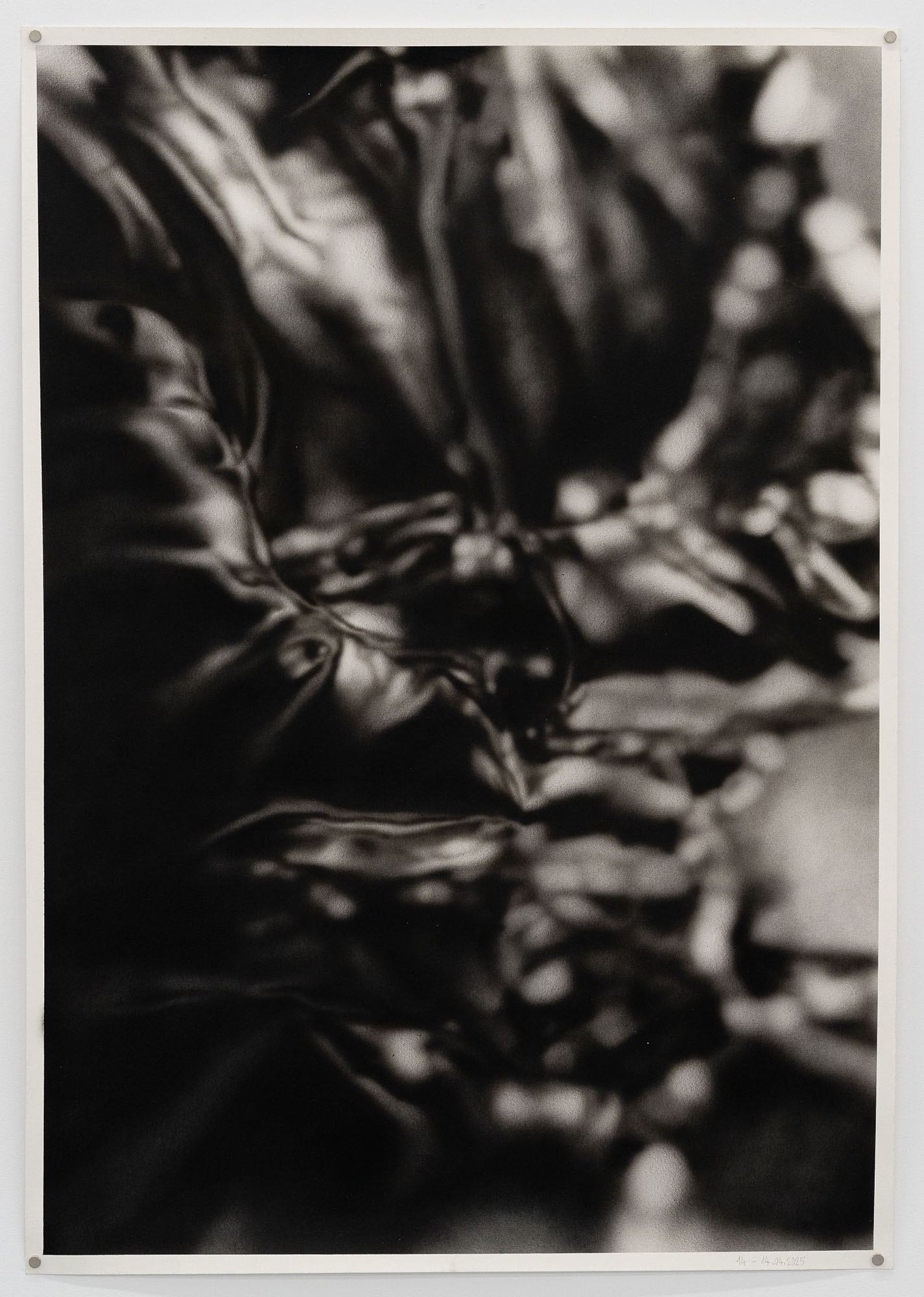

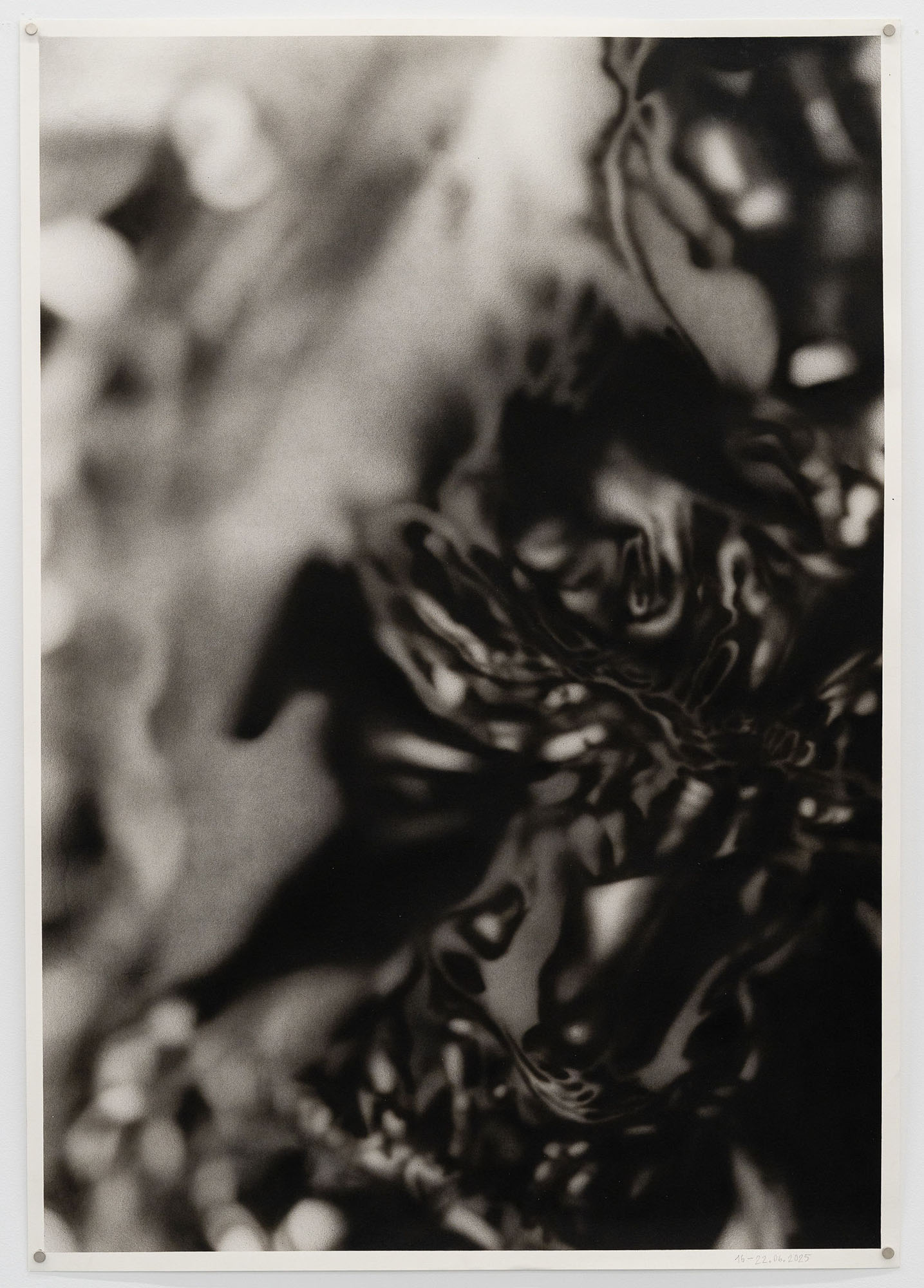

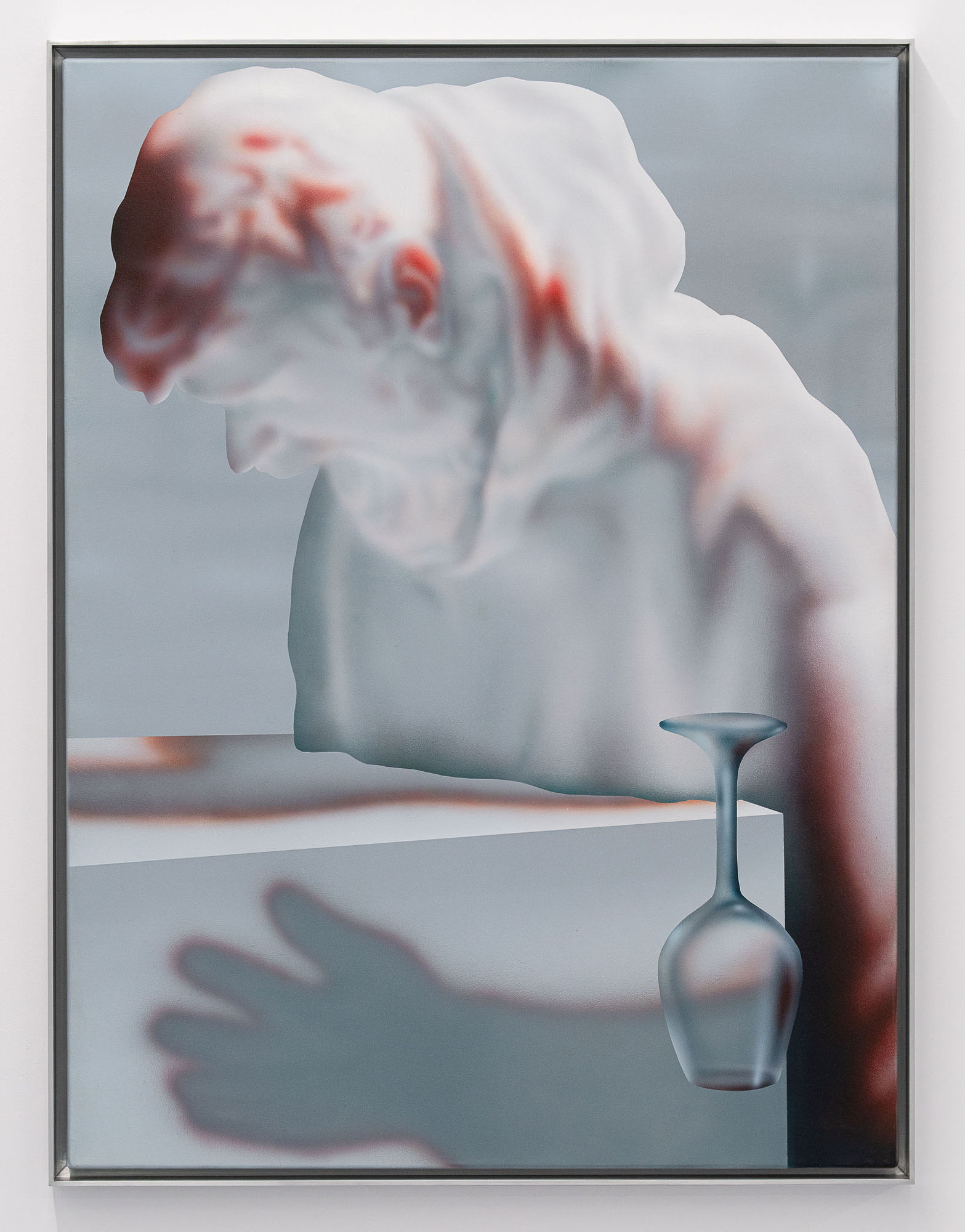

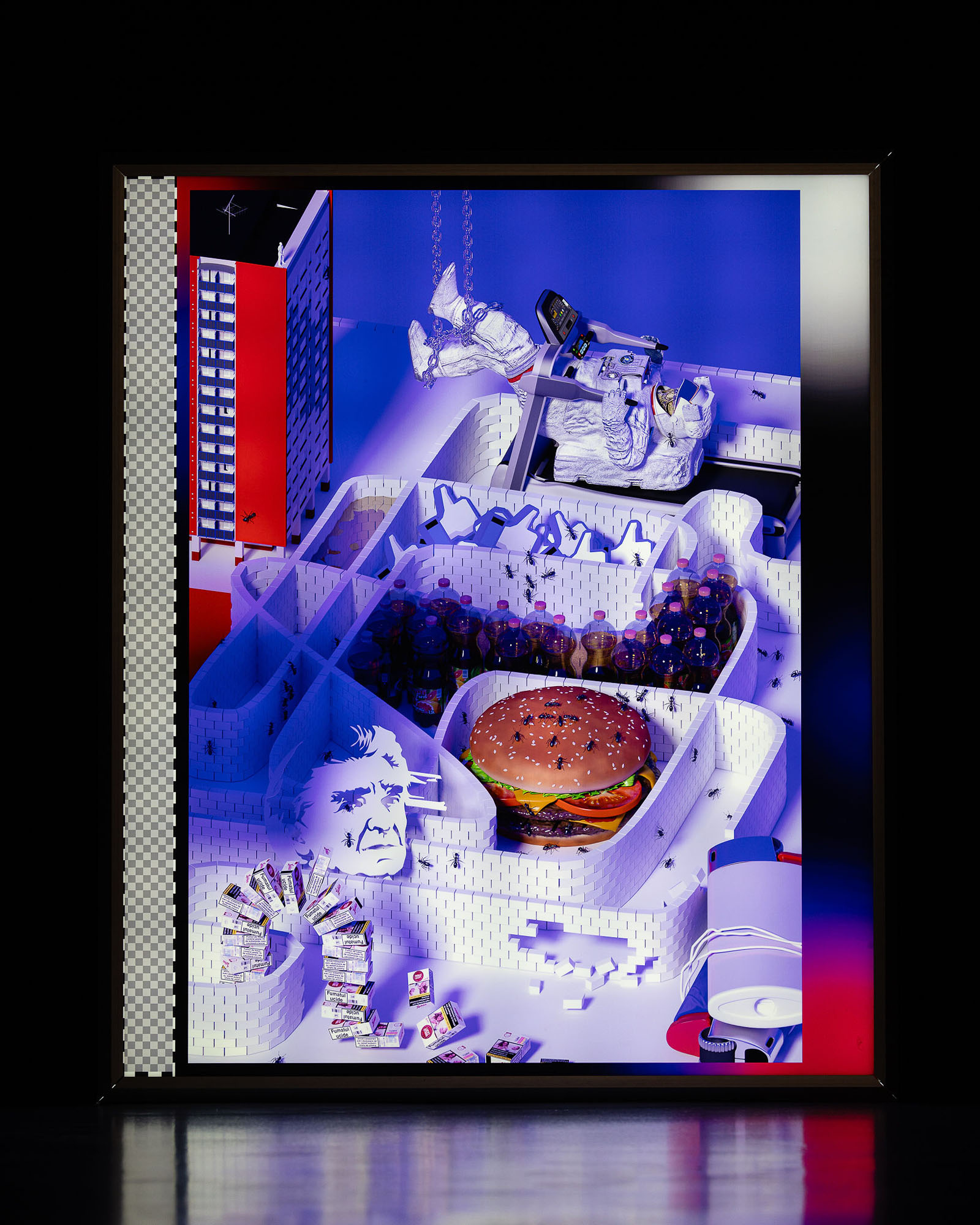

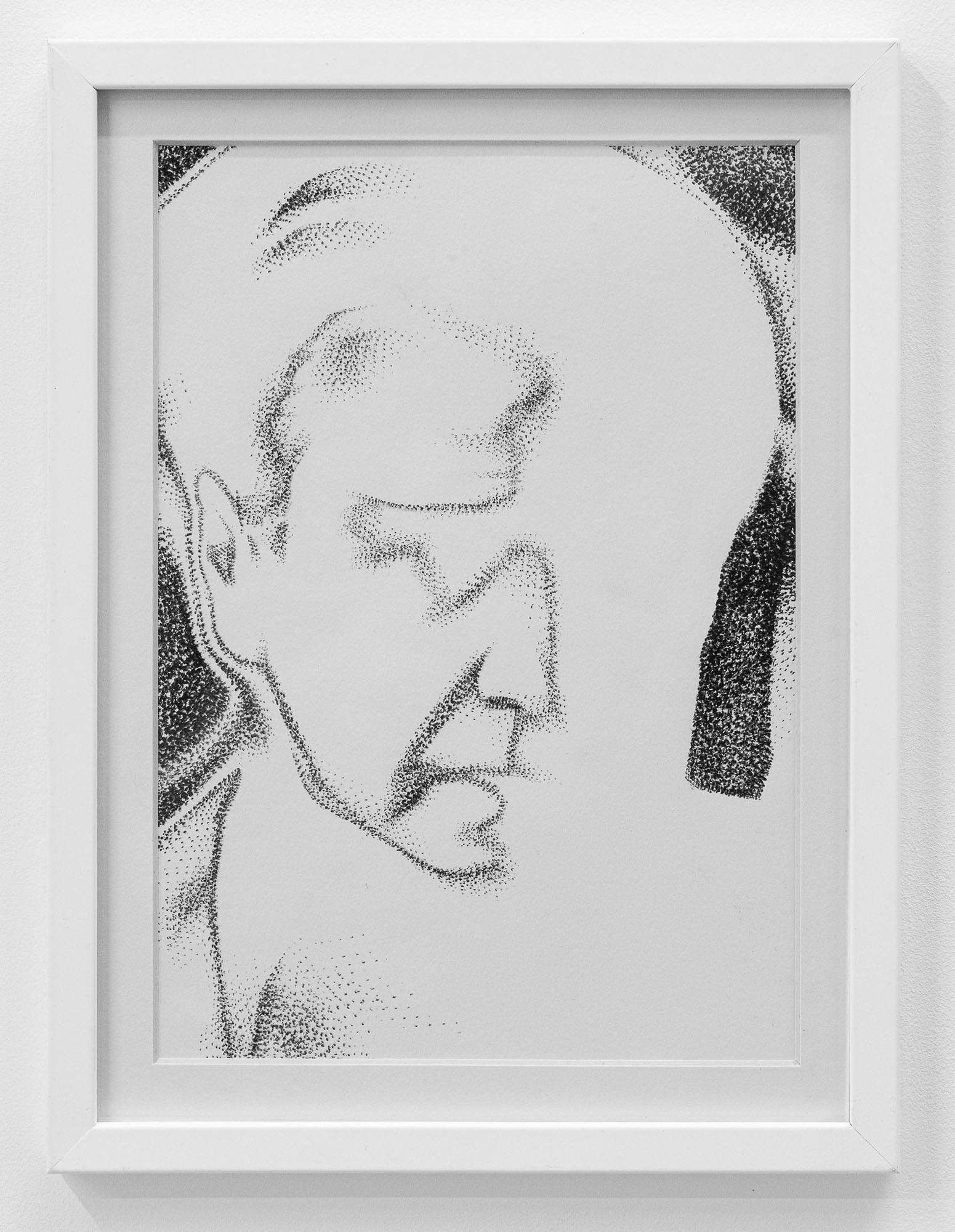

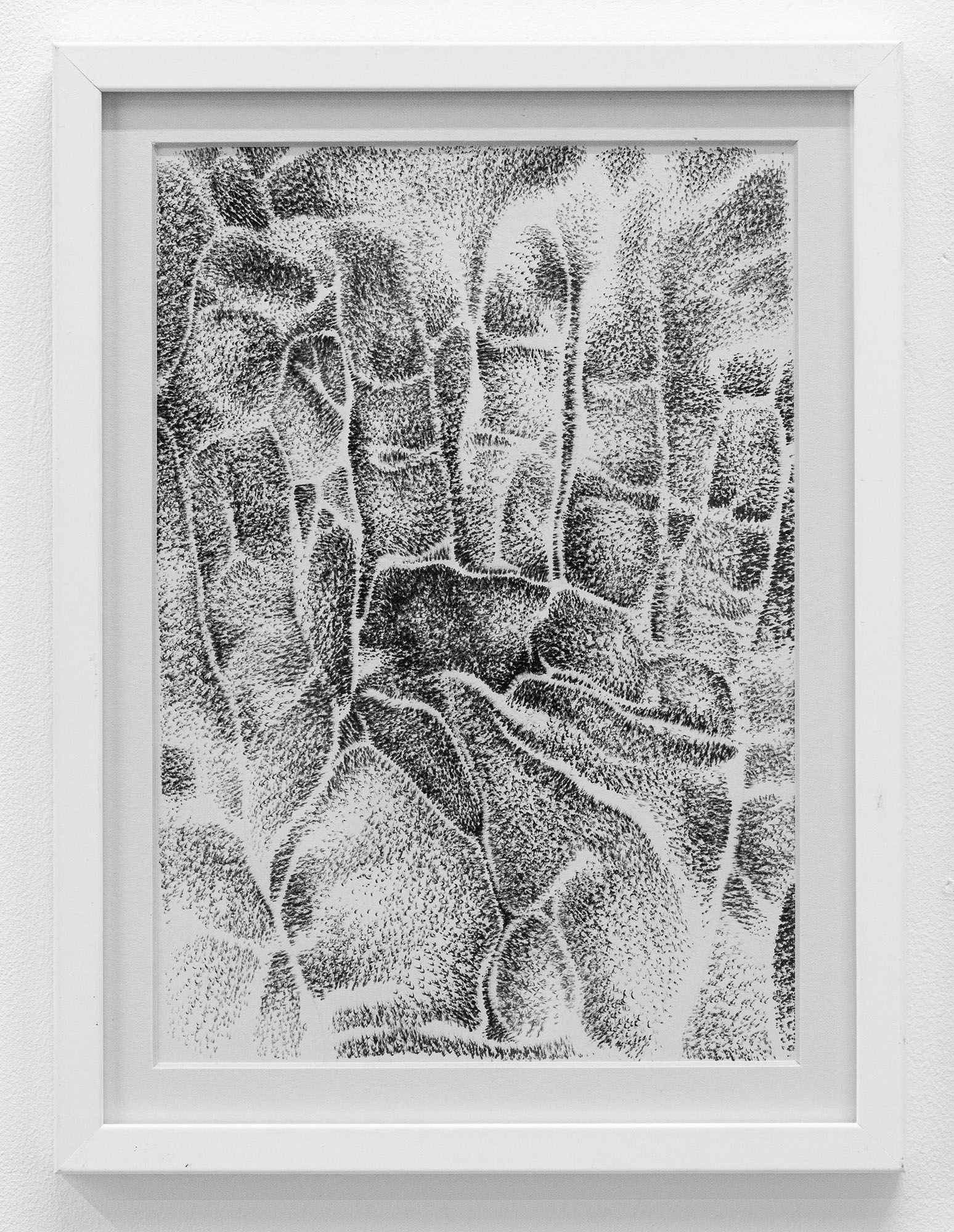

I frame this inquiry into painting within an atemporal and anthropotechnical context — one in which any trace of pigment left on a surface, whether stone, wood, or canvas, is considered painting. I do so because, beyond the apparent contemporaneity of the image-making process and the technologies involved, the finished works remain materially bound to canvas stretched on a frame and, in their conception, are autonomous artworks. While the subjects of Radu Pandele’s paintings may seem timely, the medium through which they appear continues to engage with painting’s eternal problems. On closer inspection, even the subjects themselves belong to the traditional lexicon of painting: portraits and self-portraits, landscapes and still lifes, anatomical studies and nature scenes.

In this sense, some compelling questions arise: if the works we see are determined by a canvas on a stretcher and if the proposed themes are those of traditional painting, then what compels us to say that this artistic pursuit is new or that it escapes the shadow of postmodernity? It is worth clarifying that I am not suggesting painting is simply a problem of modernity or postmodernity — historical stages we may not have fully lived through but often claim to have surpassed. Rather, my questions are meant to provoke an analytical look at how painting evolves in this post-20th-century time, more precisely after 2010 — the moment Terry Smith identifies as the beginning of a new chapter in the history of contemporaneity.

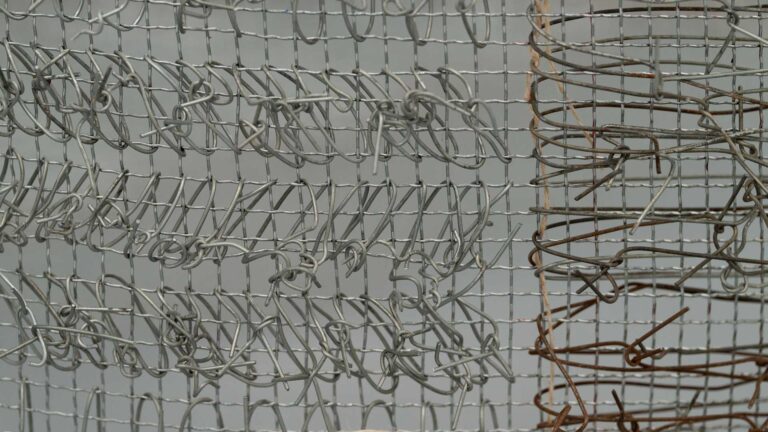

Returning to the works on display: what we have here are key moments in Radu Pandele’s artistic trajectory, with some of his most representative paintings from recent years selected to highlight both the originality of the visual language he has refined since the beginning of his career and his unique position on the map of contemporary painting after 2020. If I were to underline a few fundamental changes in this type of painting, we might note the departure from the traditional tool — the brush — now replaced by the airbrush. This shift recalls, in a historical sense, the fine mist of the Flemish masters, and in a contemporary sense, the countercultural aesthetics of graffiti and street art. On another level, the processes of preparation — such as drawing or sketching — are replaced by 2D and 3D digital graphic software. One might say that the artist’s studio has been expanded to include a new kind of space: the digital, PC-bound space.

Furthermore, in terms of interpreting or critiquing these “paintings,” it is clear that the traditional instruments of the aesthetician or art historian must be updated with tools from the field of visual studies — those that account for the impact of mass media and digital culture on the image.