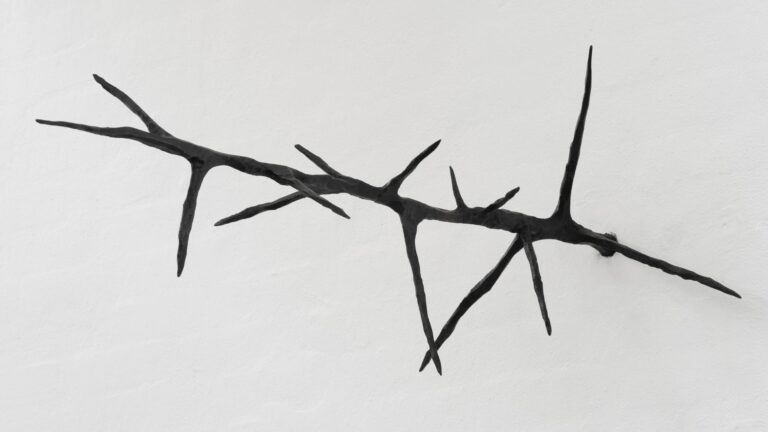

Artist: Philip Poppek

Exhibition title: How to End it

Venue: C.C.C., Copenhagen, Denmark

Date: June 1 – July 11, 2024

Photography: GRAYSC / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and C.C.C. Copenhagen

How to End It: Five Rolls of the Dice

⚁

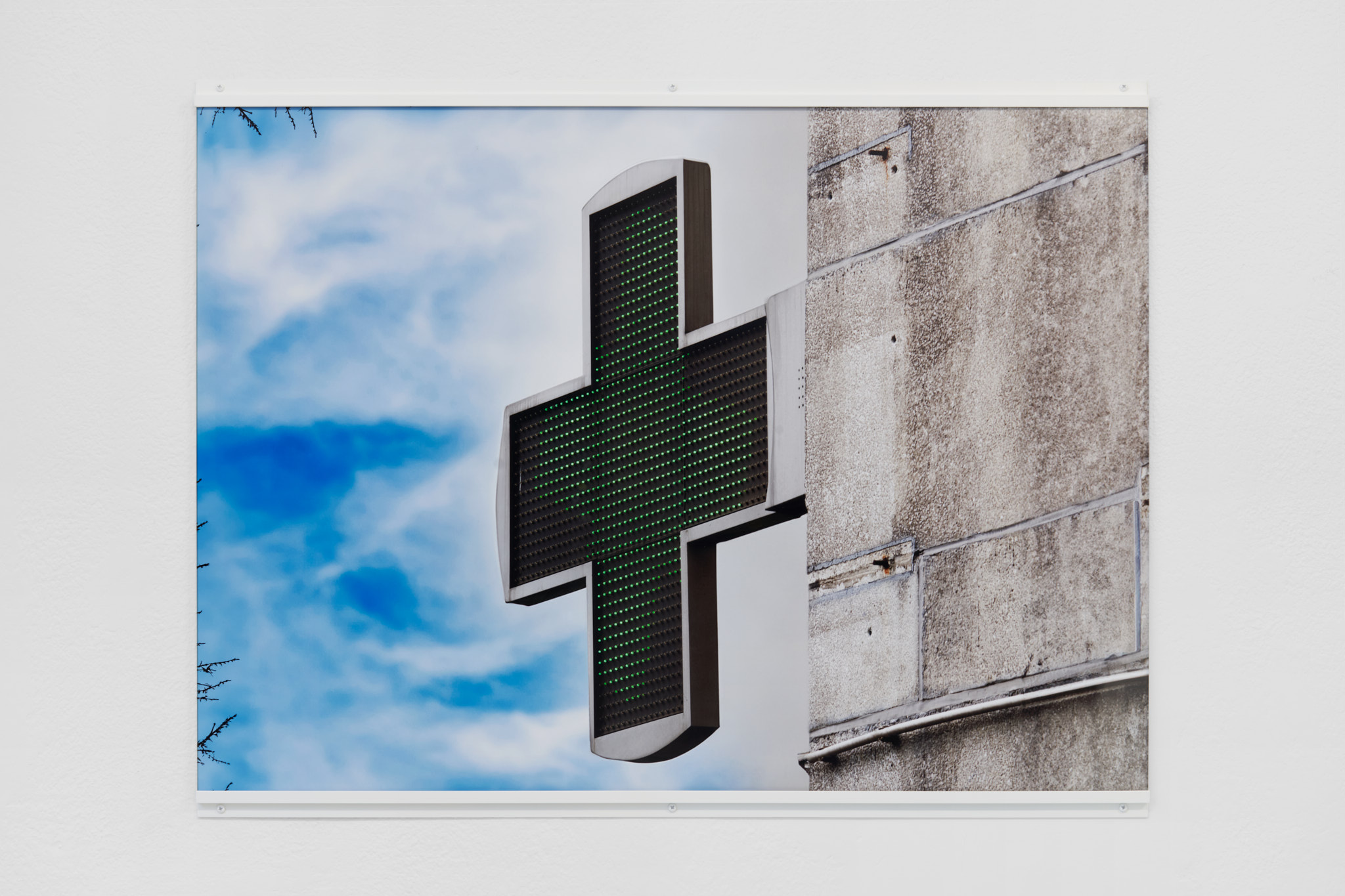

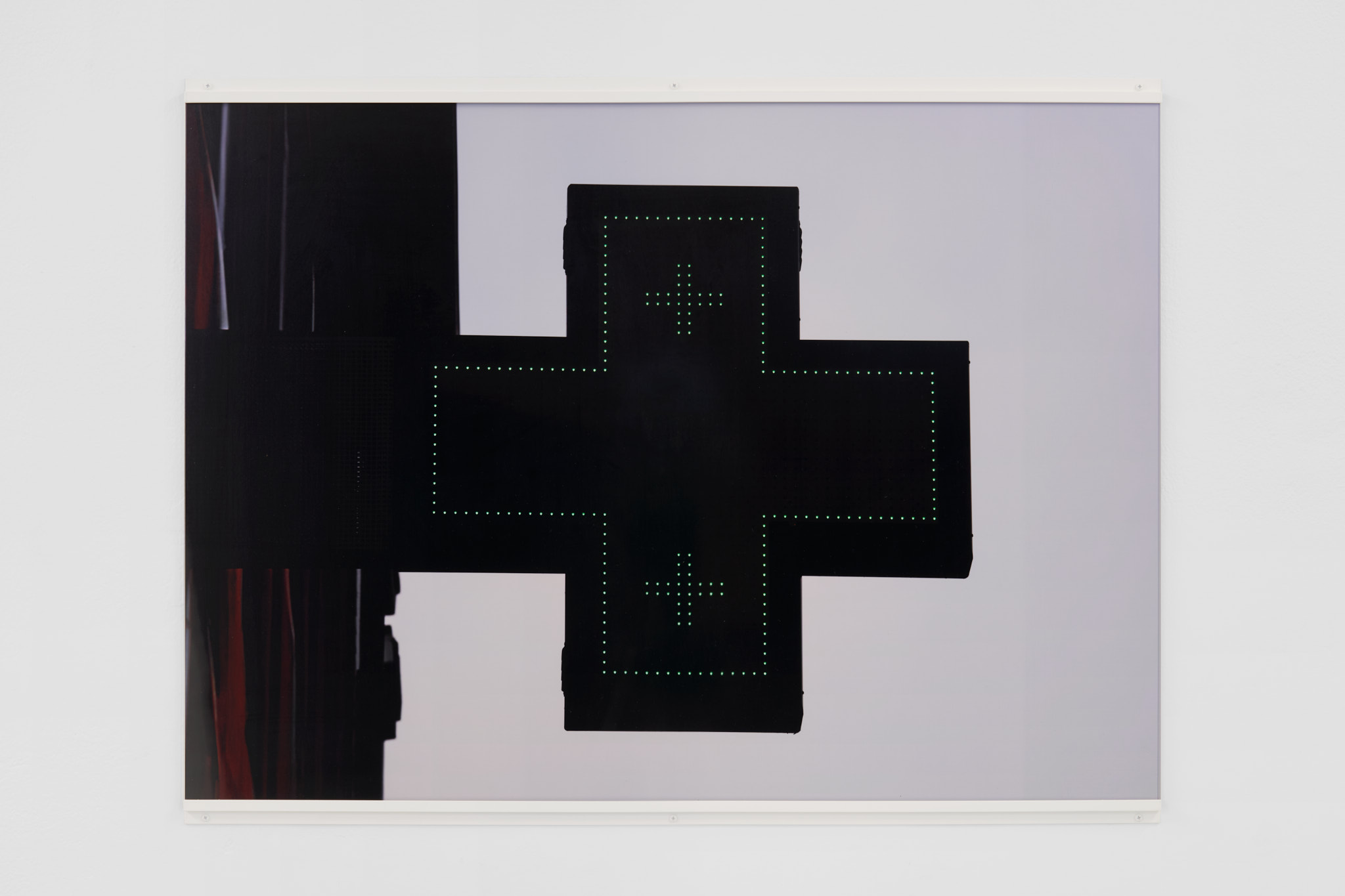

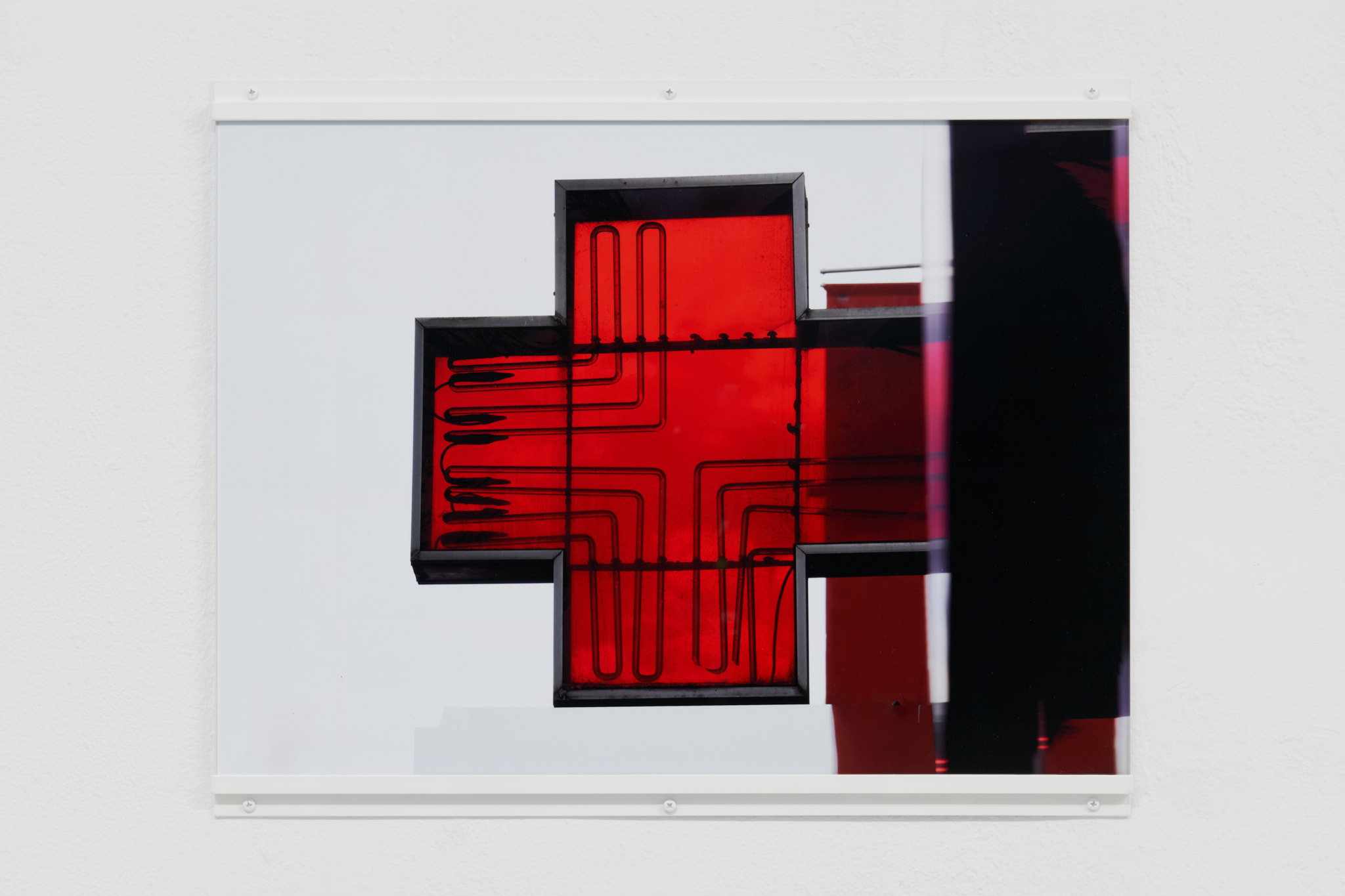

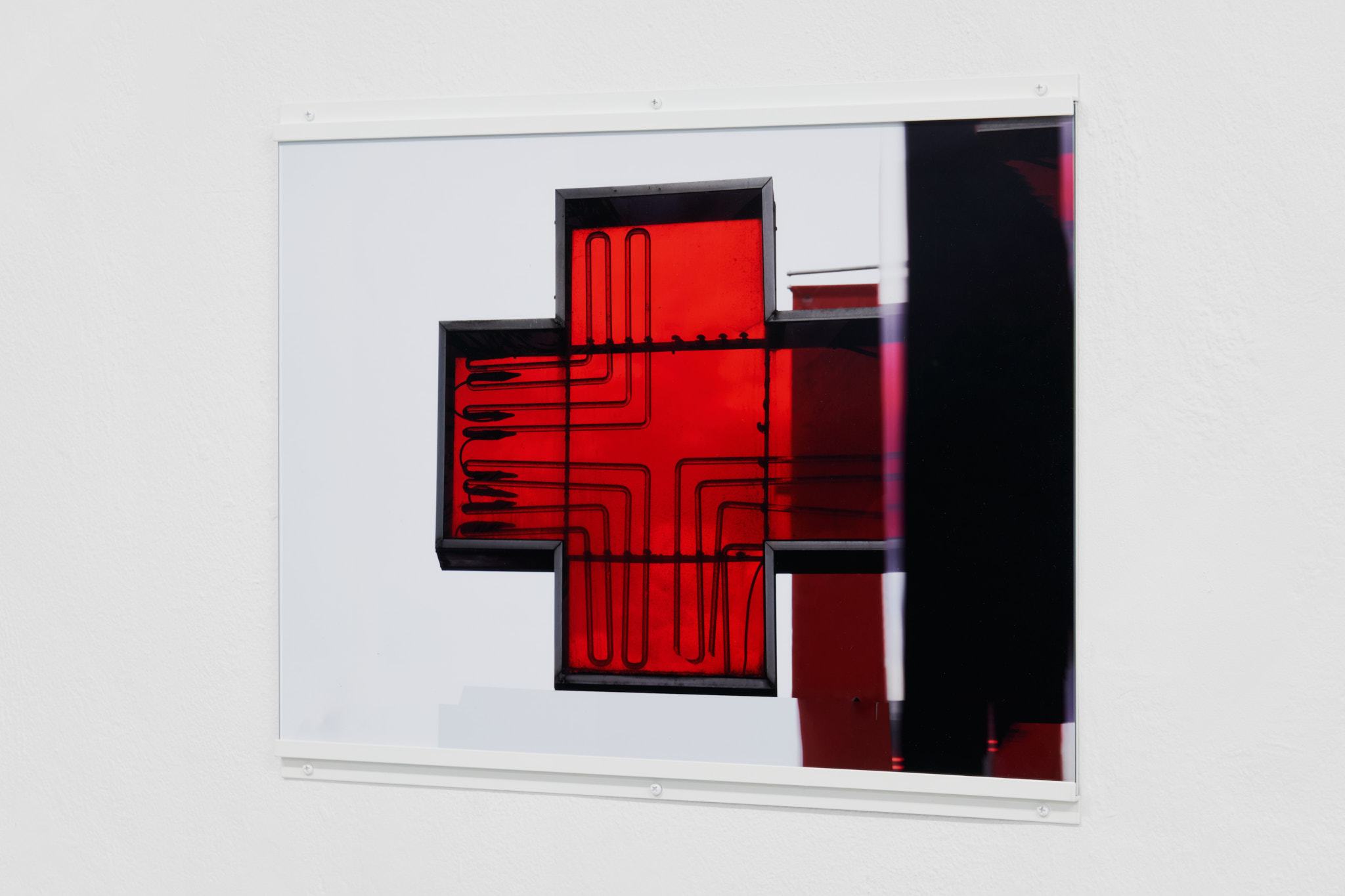

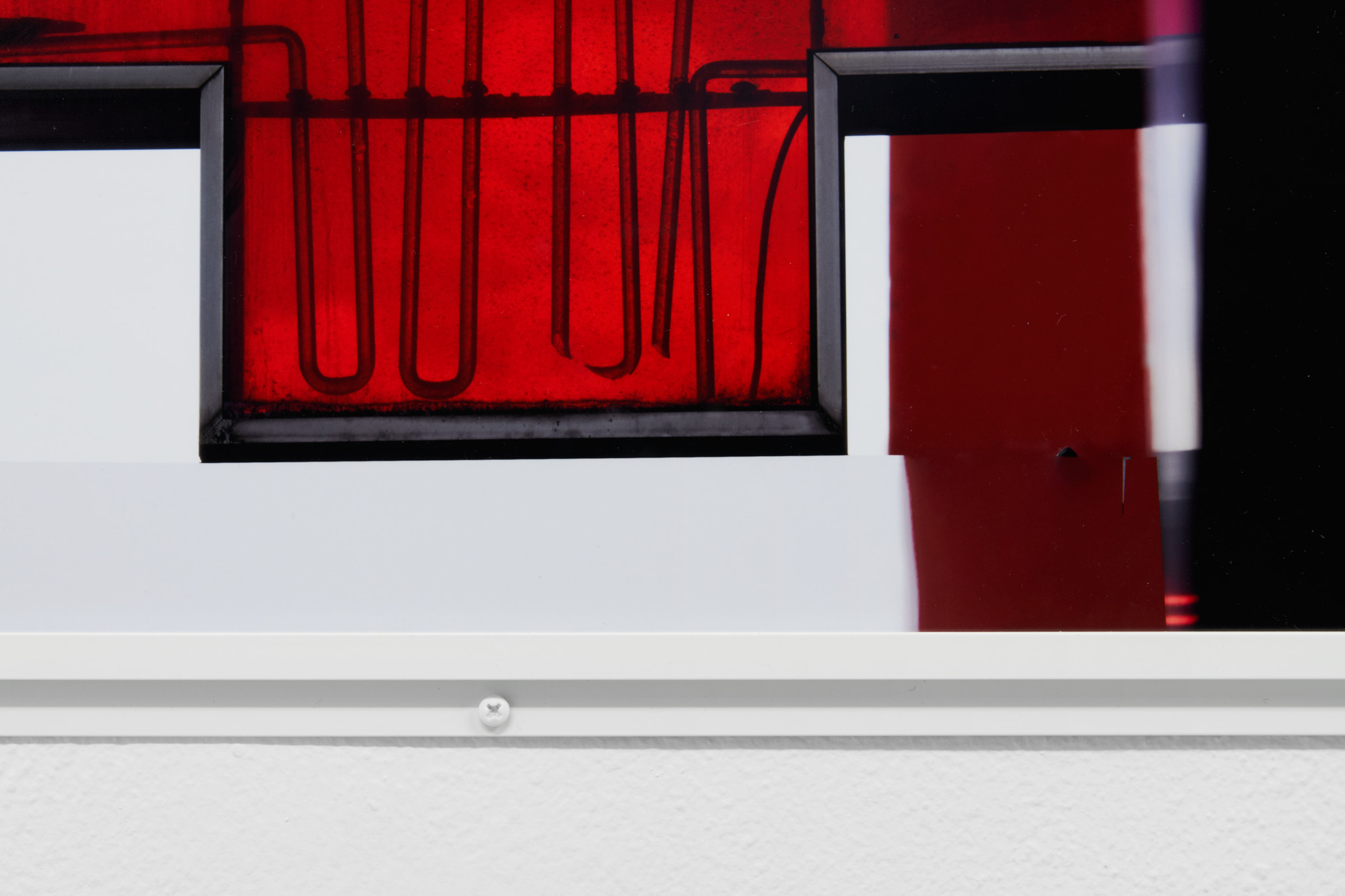

You know what it is you’re looking at. The symbol for the pharmacie/apotheek in Belgium, green is the colour. Go, it says. (In Germany it is red, he says.) The green cross is fresh and it cures ailments. You see it, you believe it. You know what it means. This is the importance of symbolisation.

⚀

This is a culture that talks endlessly about initiatives, new beginnings, fresh ideas and startups and knows little about the end. (The luxurious pettiness and small-minded obsessions with safety.) A culture of the end knows mortality is a great gift; speech is a tool for enlivening the present time; and trust comes from action not coercion. What it is unprepared for, blind to, and ignorant of, what it avoids, obfuscates and decorates is this. It doesn’t say ‘no’ to the always new, which means it doesn’t know how to say ‘that’s it, that is what I want’. The options are not endless. Stop counting. It is preferable for this news to come from elsewhere, somewhere, away from here, imposed by far away conditions. The logic of ‘far off gain’ justifies today’s disgraces. This wanting is someone else’s. This end will be insignificant as such for it may only ‘herald a brighter future’. If it ends, it ends because the hand was forced; there was no choice. Nothing will have been intended. It submits to this endless procrastination as if it were real and in so doing gives up. It gives up, it doesn’t stop.

⚄

I think of form. I ask myself, ‘What will give this thought form?’ Surely, first of all, a limit. An end to the fantasy of more (experiences) leading to wisdom. I reached this limit. I see that the next thing is largely a ruse to avoid oneself and make it about others.

⚂

‘The existence of a thing materially depends on its being articulated in language, for only in this case can it be said to have an objective—that is to say, verifiable—existence, one that can be debated by others,’ writes Joan Copjec in Read My Desire (1994). She argues that Foucault rejects the language-based model he inherited as idealistic, in favour of a battle-based one. This means, for him, we should think about war and relations power, not language and relations of sense. We could summarise this as the Foucauldian pleasure for reducing society to its inner workings and immanent power relations, and the attendant inability to articulate the mode of these immanent relations (what principle sets them up?). In language, though there is nothing transcendent, there is the unspeakable, some unstatable mode which tells of a split between appearance and being. There is a split between the appearance of things (observable facts, positive relations) and their generative principle, which does not appear (this is what tripped Foucault up). Writes Copjec, ‘His belief that every form of negation or resistance may eventually feed or be absorbed by the system of power it contests depends on his taking this point to mean that every negation must be stated.’ Indeed, for Copjec it is Foucault who is idealist, and a language-based model that is materialist. The language-based model says simply that ‘something cannot be claimed to exist unless it can first be stated, articulated in language.’ For Copjec, this is not tautology but a sort of rule equivalent to that of science (‘no object can be legitimately posited unless one can also specify the technical means of locating it’). In other words: this is how to end it.

⚃

Why do you see life as a series of problems that need to be resolved? These problems appear to energise you, make you feel you ought to ‘do something’ about them. Take this, take that, go here, go there. Oftentimes, doing nothing is the decent response. You are reminded that nothing is truly poisonous if taken at the right dose.

—Eleanor Ivory Weber, Melbourne, May 2024