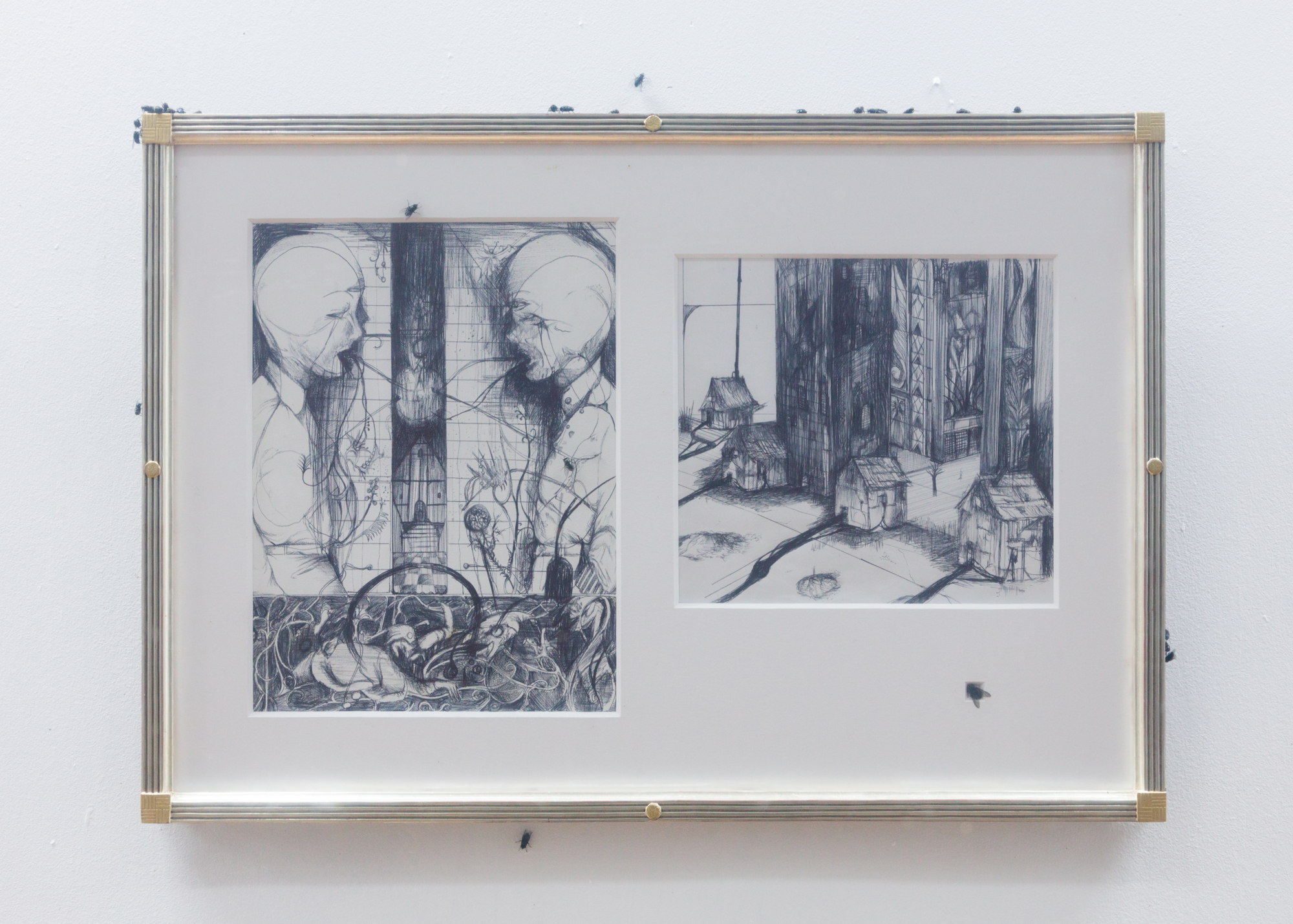

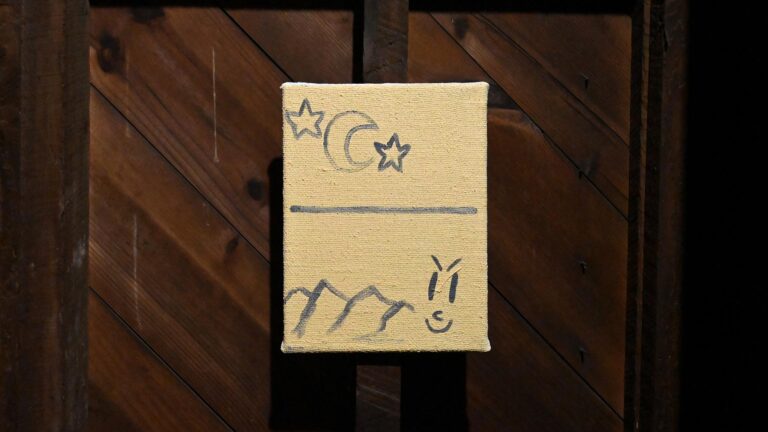

Artists: Paul Gondry and Duncan Boise

Exhibition title: C. Vomitoria

Venue: Mx Gallery, New York, US

Date: December 15, 2017 – January 29, 2018

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Mx Gallery, New York

Those days were marked as much by an obsession as they were by weakness and fits of gagging. I spent a fortune consulting pathologists and shamans, and in return they gave me tablets, tinctures and healing charms. But even as each prescription failed to cure me, and my funds began to dwindle, I came back just to hear them speak a little more of nausea and the symptom. I was bewildered by it, everything from the feeling to the idea of it- the endless causes, the types of aches and pains, and nuances in the accompanying spells of dizziness. And then there was the detailed art of reading the vomit, which came in different colors and consistencies, some of it from deeper in the digestive tract and some of it with stringy beads of blood. Each unique spill told its own story of becoming and pointed to potential diseases, ailments, curses and bitter ends. And then, despite all of an expert’s attempts to understand, there is always the simple and unexplained passing lapse.

But for as long as my unexplained symptoms persisted, so did my obsession. I carried a log and delicately noted changing symptoms and habits. I logged dietary inconsistencies, humidity levels, and air quality. I isolated variables like sunlight, gluten, dairy, and even friends, sometimes inventing excuses to avoid friends I suspected might infect me. “The girls are making dinner tonight” I’d tell them, launching into a pathetically credible tall tale to throw them off my scent and, then alone in my room with a fly ridden bedpan by my side, pour over medical tomes and documents.

Nausea, is unique in that it can act like a transmutational spell– Words alone can conjure physiological upset. When my isolation became unbearable, and I wondered if I was the cause of my own condition, I sought the advice of others who shared my symptoms. I went into the village markets and inns and found there were many like me, carrying notebooks as they excused themselves to dry heave in the gutters. When we found each other we were like over eager children just introduced. We compared symptoms and cross referenced documentation of potentially noxious chemicals. Some had written off our living hells as hypochondria, but we thrived together– we taught each other how to identify new symptoms, build better logs, write more nuanced experiential document. Lyricly layering symbol and simile, the most gifted among us would weave romantic tales of prognoses with the grand yarn of symptom description. Our sores became badges of honor and our unique stenches became warm markers of kinship and identity. It became evident that this was not a plague — a plague being one singular, sweeping, unifying affliction — we were not united by some force of nature, nor did we share in self-interested fantasy of ‘cure’. Our diseases were unique, but our spirits common; commonality epitomized by a de facto mascot– the fly.

Perhaps obsessive research into any subject has the potential to discredit its obsessed participants, but our collaborative efforts eventually made our symptoms look like something knowable– like the work of something beautiful. Stench became style. Through sickness came a fever dream of something new, of possibility, of community, of noble and heroic work that might find a shining light. We, now angrily referred to as ‘tall flies’ by the villagers, found independant purpose.

Those dreams, however, vanished the summer the ‘fly hunters’ arrived. When the villagers caught wind of our paranoid assemblies they could be found gathered in whispering crowds around puddles of vomit, spreading rumors of our newest theories of dirty factories and medical malpractice. But as soon as there was a growing distrust of their authority, there was an equal distrust of the sick and the tall flies, who were dragged from their homes to be shamed and beaten in public (it was not uncommon in those days for symptoms to be confused with causes). As an increasing number of villagers fell ill with the hysteria, and vomit flowed through the streets, a contagion of theories swept the town as if it were gossip of cheating wives and cuckolded fools. Theories of hidden foreign actors, of corrupt food regulators, of environmental stress all continued circulating until the village finally arrived at the fly, once our community’s unwelcomed byproduct, indicative of filth and neglect, but now our proud rallying icon. Suddenly every theory vanished in favor of this singular and absolute idea that the fly itself was to blame. Perhaps the villagers were weak in spirit or so jealous they could not think; Or perhaps they were so tired of the mania of speculation and the sense of being made outsiders to our budding culture they revolted.

It is no secret that a fly relishes a meal of vomit, just as it is a known fact that a fly vomits often. Vomit is a fact of her nature and she can not defend. As we know, what distinguishes the worst of architects from the best of bees is that the architect raises his structure in the imagination before he erects it in reality. And so, analogous to the Trompe-l’oeil painting of a fly upon a fruit confused for a fly upon a painting of a fruit, the people raised the fly in their imagination as the bringer of this new ‘evil’.

As our community was forcibly disbanded, the hysteria eventually subsided, and although occasional bouts of unexplained nausea and the banal existence of flies persisted, the villagers mostly returned to their lives and let that curious obsession slip into the shade of history. Sometimes when I think back to those days I wonder where our inquisitive work might have led if it wasn’t for the flies. Then again, I try to remember why I was really so entranced by the details of disease– by the colors and forms, the tactics and complexities– and if I was indeed only distracting myself. I remember those nights when theories failed me and I found myself in the darkness that shrouded 90% percent of my body, when all that pulsing mush and poisoned blood that hid in the darkness under my skin remained silent. I remember those nights with my brothers and sisters when I was too excited and unabashed to even brush the flies from my vomit encrusted lips. I would sing our opening prayer:

OhLoRdE, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.