Artist: Paolo Brambilla

Exhibition title: Capriccio

Venue: Museo Ettore Fico, Turin, Italy

Date: June 21 – September 13, 2017

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Rage Over a Lost Penny, Vented in a Caprice

– Notes on the Work of Paolo Brambilla

by Niekolaas Johannes Lekkerkerk

The work by Paolo Brambilla is marked by speeches, perhaps even haunted by the ghosts of previous states. By taking forms and shapes, following different pathways, mimicking movements, by shadowing and repeating gestures, he has established a rich and dense vocabulary of materials, symbols and references, associatively moving between a variety of historical registers. An art object as a mold of multiple approaches. Or, in other words still, the artistic process as an amalgamation, a synthesis of radically diverging scales, rhythms and sources into a (seemingly) congruent whole that is an art object. Or is this folly to begin with?

In his new series of work—marked by the overarching title Capriccio—Brambilla has sought for the conceptual integration between the time and space of fiction and modes of aesthetic and artistic production. To briefly summarize, in musical annotation the term capriccio classically marks a change in the tempo, and possibly in the style of the composition. Quite literally denoting the idea of ‘following one’s fancy.’ As an art historical genre gaining prominence in the 17th-century, capriccio—whilst remaining a category of (landscape) painting open to free associations—was bound by a different ruleset, recognizable for its architectural fantasies as the primary subject. Here, conveyed moods and stylistic elaborations are the key pictorial motifs, often depicting ancient roman ruins covered in foliage, dilapidated aqueducts, crumbled statues and columns, combined with then-current monuments and highly ornate buildings. The human figures in these paintings—often called ‘staffage’—were equally employed as decorative scaling elements to enliven the pictorial dynamic and grant a sense of plausibility to the likeliness and occurrence of the scene, to legitimize and add credibility to its staging.

For Brambilla, however, the interest in capriccio lies with its mechanism to unify sources of different origins and signification within a single unit. To essentially explore how historically stratified image material and information could be stripped, aesthetically adapted and reapplied as to constitute a new patchwork and constellation of meanings. Thus, a concern with capriccio as mechanism, a translation table for associatively unifying and transforming different temporal rhythm’s into a single coalescing whole.

Furthermore, Brambilla employs capriccio as a basis to explore and explicate the notion of ‘folly,’ an architectural genre similarly capitalizing on tropes of fakery and make-belief within the built environment—commonly part of great English estates and in French landscape gardening, reaching its peak in the 18th-century. As costly, decorative and ornamental architectural structures, follies were purpose-built but served no practical function. Ranging from towers, belvederes, castles, temples, abbeys, pyramids, lodges, beacons, pavilions, to entire rustic villages, the folly could be marked for its willful tendency to mimic the alogical invocation and representation of different continents and historical eras. Thus, essentially, a loss of factuality and truthfulness, to its recovery in the key of fiction. An architectural fiction with a symbolic and emblematic function, pleasurably celebrating the schism between function and functionality, purpose and purposelessness, pretense and pretentiousness. Regarding the latter, it is interesting to read the folly as a site of referential signification, playfully invoking a sense of bygone eras and places culminating on the level of its surface, as a surface effect—extending before itself, actively staging an a-historical masquerade whilst pretending to be nothing other then its truthful self. In other words, to believe in a folly is to willingly and knowingly suspend one’s idea of disbelief, to cultivate and maintain a sense of pretense (the folly’s new clothes!), without showing that the stage-setup is an air castle, a pipe dream: the folly as a fiction that is nonetheless mighty real and historicized before our eyes. Within our present-day age, a continuation of the folly exists in the shape of theme parks, fairs and other temporal structures for events—as strategically applied (technical) mechanisms to generate attraction and attention, to create momentum within a perceptual arm’s race.

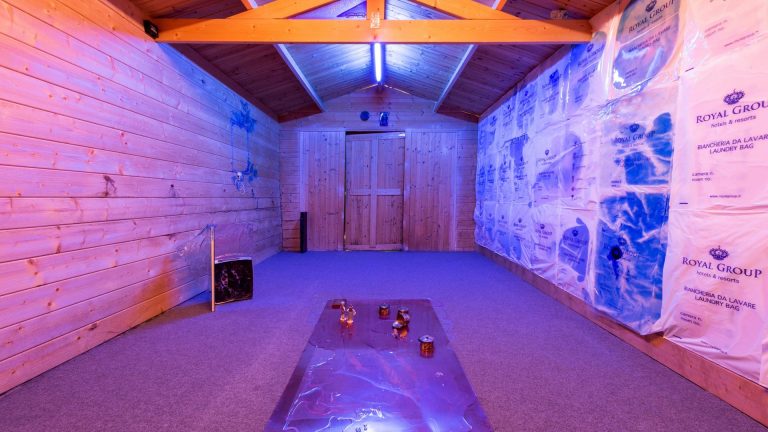

In Brambilla’s new series of work one may recognize those previously discussed elements and mechanism active in both the genre of capriccio and the folly. Taking the shape of two installations and a smaller intervention at Museo Ettore Fico in Turin—one located at the terrace of the museum, the other in its project space, and the latter in the museum’s cafeteria—Capriccio could be said to be constituted as two respective but interrelated tableaus. Grouping different media, among screens and room dividers, sculptures and rendered objects, support structures, and an overall aesthetic intervention to set the ambiance of the space, their common ground is an ornate and exuberant aesthetic, and perhaps more importantly, their depiction and redistribution of a borrowed vocabulary of forms, shapes and contours we come to grapple with, but cannot quite recognize or seem to fully comprehend.

This vocabulary of borrowed forms is equally present in previous serial constellations—such as Brambilla’s recent project SUPERHYPHENATION (2017). Here the work took the shape of variously-scaled installations grouping and combining different materials, among digitally printed textiles and stretches of curved aluminium and metal strips, rope, brass wire and wood—the latter sometimes employed to hold and suspend the work mounted against a wall, at other times organically flowing on top of the textiles lushly draped on the floor. The textiles—with their organic flowing patterns and cryptic iconographical image renderings on pastel-colored satin—created narrative arcs between the works, dispersed around the exhibition space. The narration somewhat remaining in the space of the opaque, with high levels of abstraction, one might be inclined towards a reading of the work on a more overarching level, establishing a stable pattern of recognition through the repetition and permutation of forms—an assimilation of information sources, both natural and artificial, actual and virtual.

Indeed, it may be argued that Brambilla is less concerned with the respective signification of each pictorial element within these constellations, but rather aims to emphasize a more speculative and formal approach looking into different methods and mechanisms of collection, (re)production and transformation. In the case of SUPERHYPHENATION this mechanism concerned the notion of diaspora, as a means to unify single dispersed elements and units into a relational and networked patchwork occupied by different sources simultaneously, whilst maintaining their respective scale, reach and temporality. Thus, the idea of diaspora as a means of production to move from single to plural, from unity to multiplicity—the work as a vehicle to show how different actors and entities flow, connect and travel within our present-day reality, rather than an investigation into what they might stand for and communicate on an individual level. With the Capriccio series comparable tendencies are at work, however in this case the movement is more vertical than in the case of diaspora, and rather unifying elements from different historical stratifications and registers, to similarly explore the ways in which graphic and pictorial regimes can co-exist on a single plane and within a single unit. In so doing it is important to note that Brambilla’s practice is essentially process-based, researching and showing how different sets of artistic approaches, methodologies, and their underlying methods dictate and mark the ground for the ways in which (image) material may be presented according to the logic of the respective approach—diaspora, folly, capriccio, and so, and so forth.

On a first impression, Capriccio comes across as overly stylistically cohesive and formally balanced, to the extent of becoming a mise-en-scène predominantly indebted to its decorative underpinnings, its overall glossy and veneered outlook and aesthetic. A self-contained micro-cosmos, its floor paved with a reflective golden substrate, the space dotted with different modular furnishings and amorphous outer-worldly objects, marked by its two laser-cut panels flanking each other at the entry of the project space, as if one were to enter a sci-fi time capsule. However, these things are not born in a vacuum. That is to say, although presented as a seemingly congruent whole, the installation is more of a life continuum in which ornate emblems drawn from different sources are solidified in the process of allocating forms to physicalities. A contemporaneous approach to capriccio, freely associating materials that seem to be unrelated but nonetheless become related in their ‘fantastical’ unison. This idea of the ‘fantastical’ or the ‘mirage’ is extended at the terrace of the museum, presenting a number of sculptures in the shape of curved tubes with graphic elements on the surface, the tubes in turn emanating different flower and fruit scents from the candles they hold on their interiors. Through the overlaying ambiance and thematic, so to speak, the various elements and works are lifted and renegotiated to circulate within a feedback loop that is not quite connecting the dots. Deliberately not reaching full circle, as the symbols, icons and graphs depicted on the different surfaces may come to reference a life outside of the newly-constituted pictorial frame and spatial container, but are aesthetically synchronized and placed on an equal footing as to introduce a new standalone temporality. A deliberate sidestepping to avoid becoming part of a larger encapsulating reality.

Brambilla’s Capriccio as a both an exterior and interior folly that is inscribed into a larger contemporaneous network of significations. A holistic unit that is constantly becoming, but never quite arriving by suspending and shrouding the origins of the various references and trace elements present in the space into an oblique and self-referencing system.

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Screen #1, 2017, laser-cut digital print on forex applied on foamcore, 165x220x2 cm (front view)

Paolo Brambilla, Screen #2, 2017, laser-cut digital print on forex applied on foamcore, 165x220x2 cm (front view)

Paolo Brambilla, Screen #1, 2017, laser-cut digital print on forex applied on foamcore, 165x220x2 cm (detail back view)

Paolo Brambilla, Screen #2, 2017, laser-cut digital print on forex applied on foamcore, 165x220x2 cm (detail back view)

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, There’s someone ringing at the door, 2017, laser-cut and laser-engraved poplar wood panel, wood stain, 57×40 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Capriccio, exhibition view at Museo Ettore Fico, Turin

Paolo Brambilla, Thisplay, 2017, laser-cut and laser-engraved paulownia wood panels, wood stain, aluminum, fir wood, polyurethane mold, plexiglass, digital print on cotton, rope, synthetic clay, oil paint, adhesive velvet, 82x70x40 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Thisplay, 2017, laser-cut and laser-engraved paulownia wood panels, wood stain, aluminum, fir wood, polyurethane mold, plexiglass, digital print on cotton, rope, synthetic clay, oil paint, adhesive velvet, 82x70x40 cm. (detail)

Paolo Brambilla, Thisplay, 2017, laser-cut and laser-engraved paulownia wood panels, wood stain, aluminum, fir wood, polyurethane mold, plexiglass, digital print on cotton, rope, synthetic clay, oil paint, adhesive velvet, 82x70x40 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Skulp, 2017, synthetic clay, acrylic paint, crystal clear acrylic spray paint, 18x18x14 cm

Paolo Brambilla, PP, 2017, synthetic clay, acrylic paint, oil paint, PVC wire, 50x50x13 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Frescogarden, 2017, laser-cut and laser-engraved chromed plexiglass mirror, 57×40 cm

Paolo Brambilla, sq/ID, 2017, synthetic clay, acrylic paint, oil paint, crystal clear acrylic spray paint, 9x13x25 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Gagagator, 2017, digital print on plexiglass, 30×43 cm

Paolo Brambilla, Goya’s SPA, 2017, aluminum, flowers and fruits scented candles, flowers and fruits scented oils, 300x50x10 cm each. (day view)

Paolo Brambilla, Goya’s SPA, 2017, aluminum, flowers and fruits scented candles, flowers and fruits scented oils, 300x50x10 cm each. (night view)

Paolo Brambilla, Goya’s SPA, 2017, aluminum, flowers and fruits scented candles, flowers and fruits scented oils, 300x50x10 cm each. (night view detail)

Paolo Brambilla, Goya’s SPA, 2017, aluminum, flowers and fruits scented candles, flowers and fruits scented oils, 300x50x10 cm each. (night view)