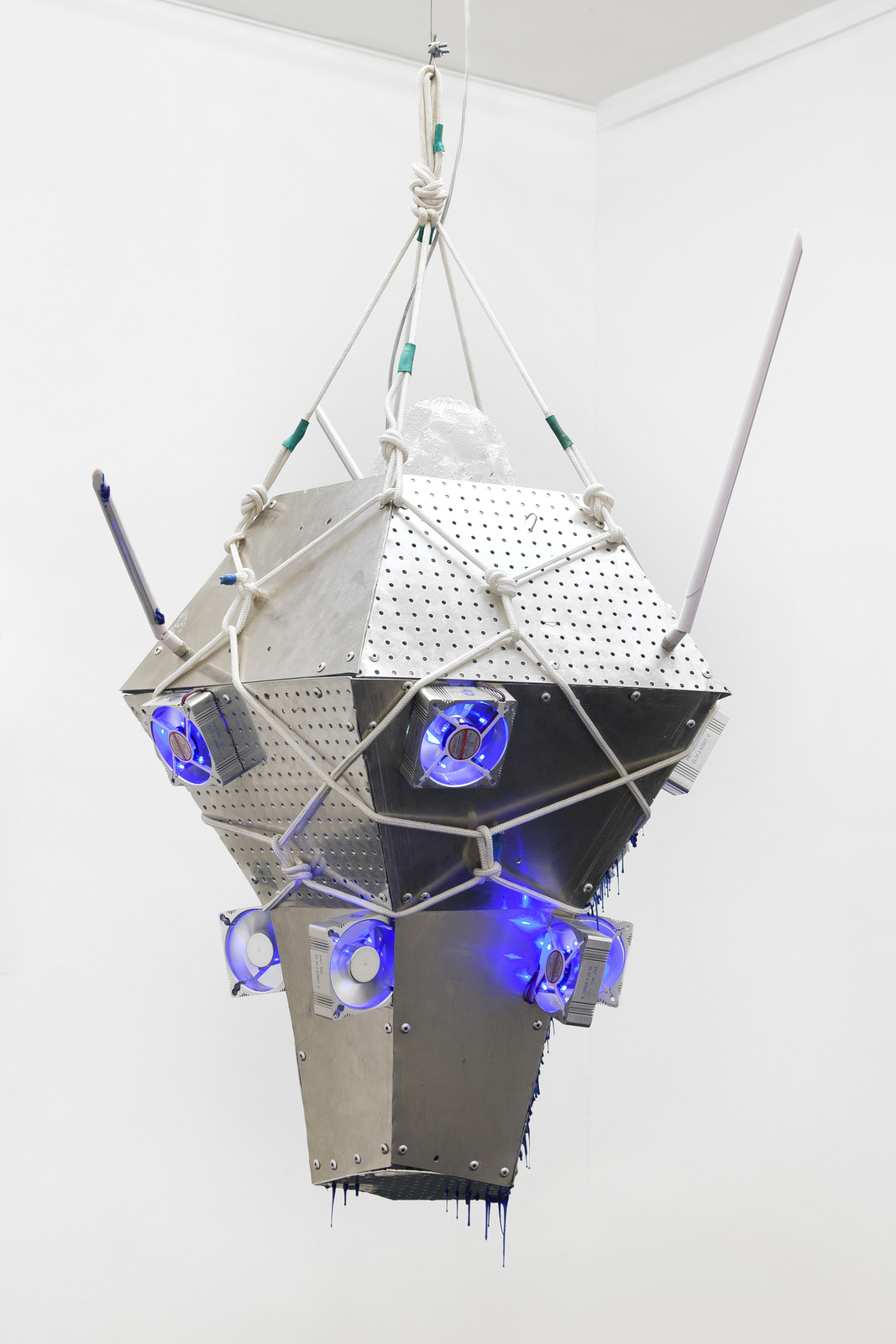

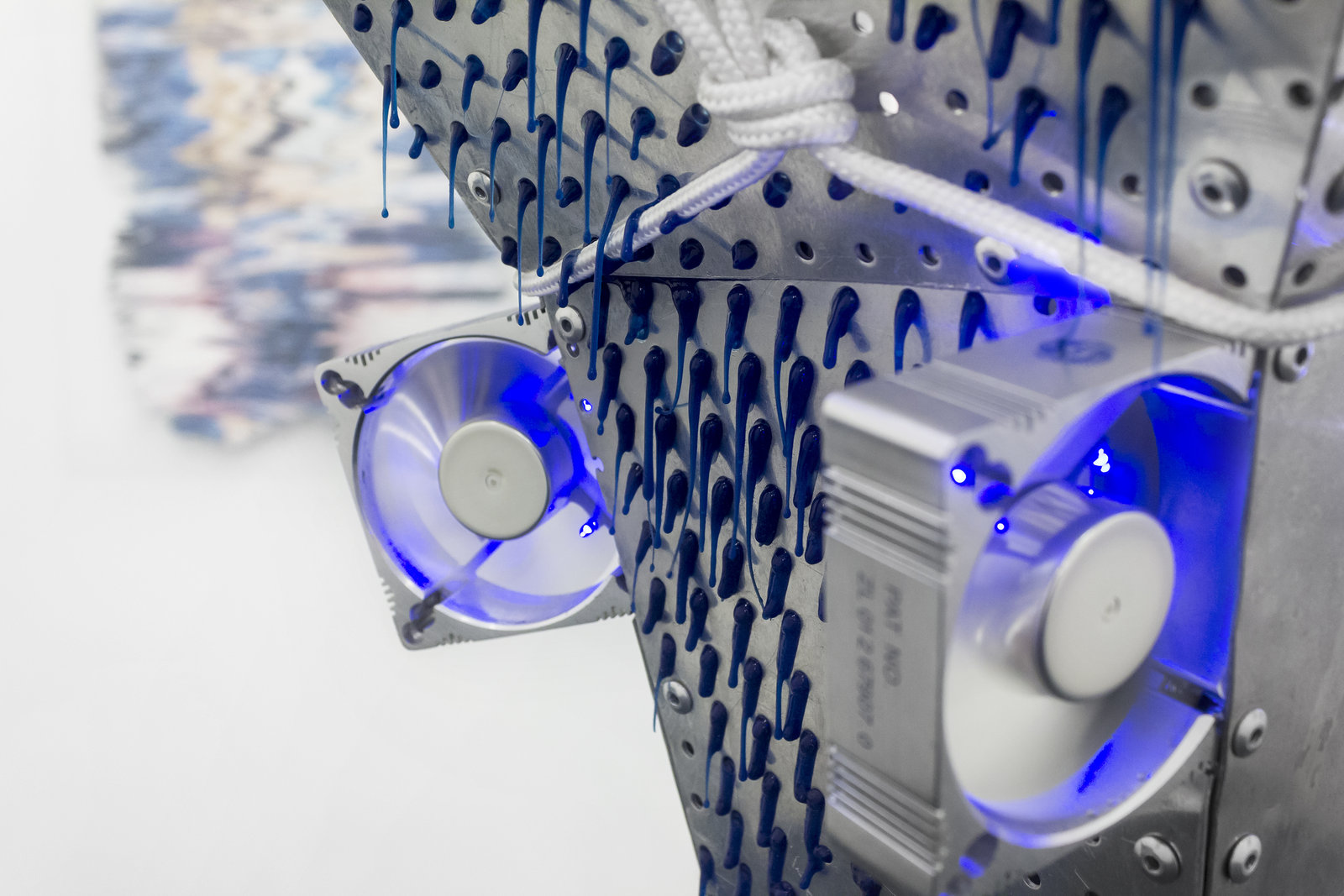

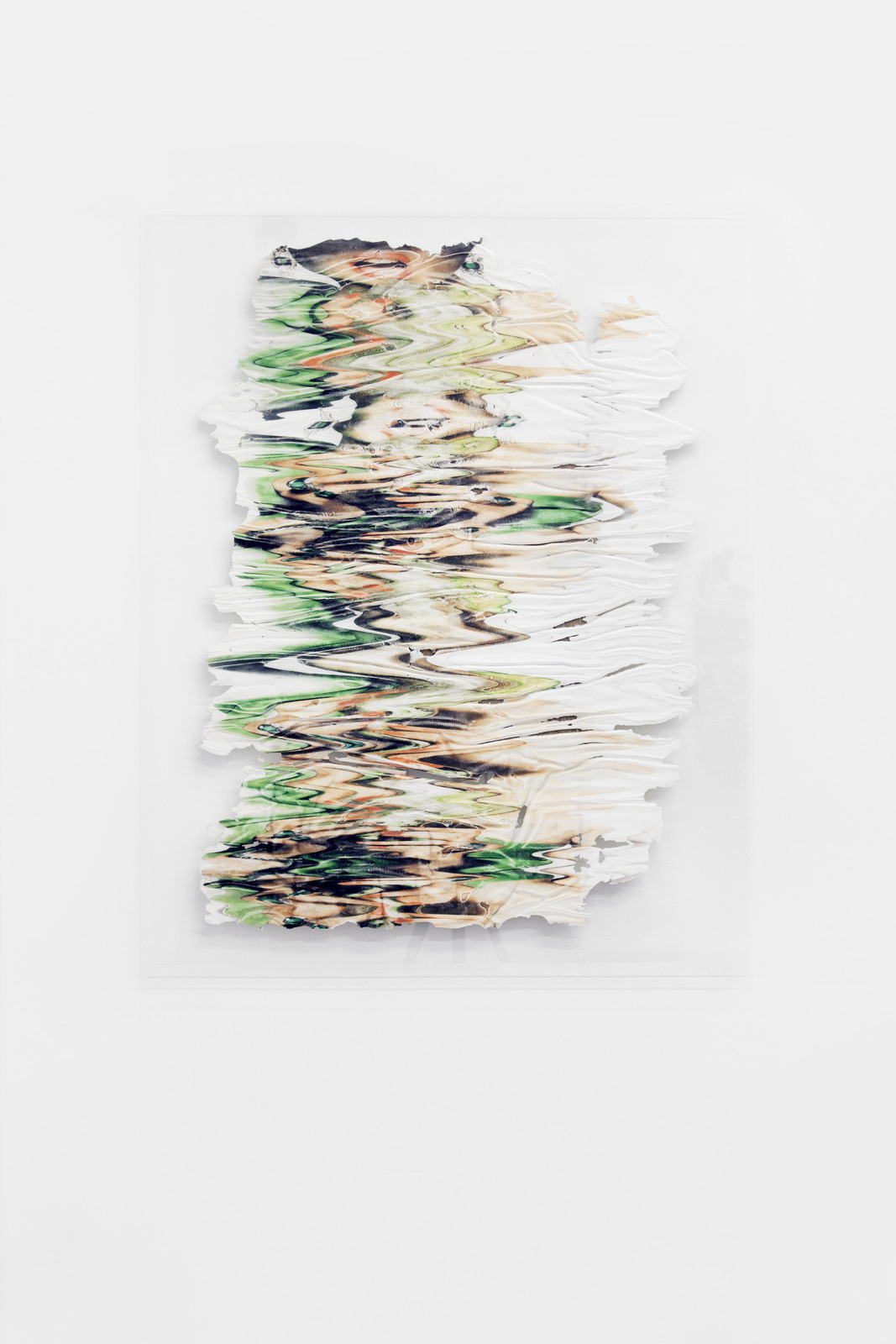

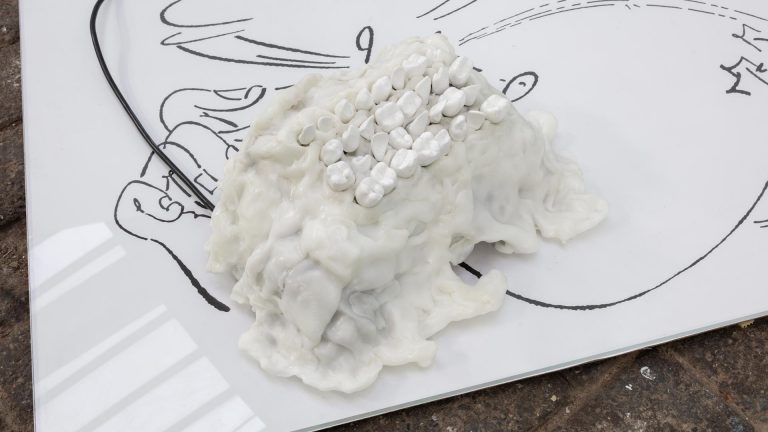

Artists: Alix Brandenbourger, Tatiana Defraine, Théo Demans, Will Pollard, Tom & Arthur

Exhibition title: OPTIONS

Venue: Deborah Bowmann, Brussels, Belgium

Date: September 12, 2016 – January 7, 2017

Photography: Ludovic Beillard, all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Deborah Bowmann

Most consumers (85%) say they prefer to shop in stores because they like to touch and feel products before they make a purchase decision.

It is not uncommon, when I’m in love, to find myself in a state of disbelief regarding the very existence of the object of my love. Are they really there? How could they be? If I touch my hand to the side of their face, perhaps I can prove that they are. I will try this several times a day. It is curious how love makes scientists of us like this; we check predictions against earlobes and collarbones. But we are not alone in our part-time empiricism.

The Apostle Thomas, in the Gospel of John, refuses to believe his fellow apostles when they tell him that the resurrected Jesus has appeared to them. Thomas declares that he will not believe it until he sees Jesus for himself and touches his wounds. It’s for this reason that ‘doubting Thomas’ now denotes a sceptic.

Thomas is presented with an opportunity to rid himself of his doubt soon enough: Jesus appears again and this time invites Thomas to thrust a hand into his side. There are various schools of thought on the question of whether or not Thomas takes up the invitation — that is, whether or not he dares to stick his fingers in the flesh of the body before him. Caravaggio, famously, was happy to imagine that he does (see: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas), though the point is of course that, to the extent that an ideal of religious faith is concerned, he shouldn’t have needed to. He shouldn’t have needed to touch in order to know (and thereby to believe), because his faith should have sufficed. But what knowledge of the other does touch offer in any case?

‘How good it is to not understand you’, Hélène Cixous writes, seemingly to her daughter, in ‘What is it o’clock? or The door (we never enter)’. This lack of understanding persists despite caresses and closeness, because intimacy always includes irreconcilable distance. The space produced between people remains a ‘secret, unknown country — thus without limit’, precisely because the other cannot be really known or possessed:

from very near as from afar, you caressed nearby as from afar, without any familiarity, contemplated belly to your earth like contemplated from the ground up, you pure manifestation of you, you moon, you other, my togetherness with you I will never know, but it exists.

But the necessary space of not understanding is in itself joyous:

Sometimes in the morning I look at my daughter, and with happy surprise I do not recognize her, my child even, I do not recognize her. The benediction is to be able to say to the beloved: we are going to turn thirty, forty, can this be, and I don’t understand you!

Hélène Cixous, ‘What is it o’clock? or The door (we never enter)’, trans. Catherine A. F. MacGillivray, in Stigmata: Escaping Texts (London and New York: Routledge), pp. 57-83.

-Will Polard, 2016