Italics, Nicole Wermers’s first solo exhibition at Deborah Schamoni, features two series of sculptural works. Domestic Tails comprises a group of hand-sewn tails in faux fur of different colours and lengths variously configured. Some are rolled out from cable or hose reels, some hang from the wall, whilst others snake across the floor, traversing the room. By contrast, Fainter on posh crisps is a series of clay sculptures of female figures in voluminous dresses, standing on bags of crisps, seemingly frozen in the moment of fainting, in descent towards the ground.

Inclining is a central theme of the exhibition. It is even indirectly inscribed in the title of the exhibition, the eponymous Italics referring to text written in a cursive slanted, typeface. In 2024, Wermers designed a font called Recliner (Bold) for her exhibition that year at the Jessica Silverman Gallery. When written in this typeface, each character leans backwards – sometimes onto the preceding letter – thus reversing the dynamism usually suggested by italic script, and instead presenting characters in modes ranging from relaxed to exhausted. Wermers’s script thus also highlights the invisible work that fonts and typefaces do via their design to subtly influence consumers’ purchasing decisions.

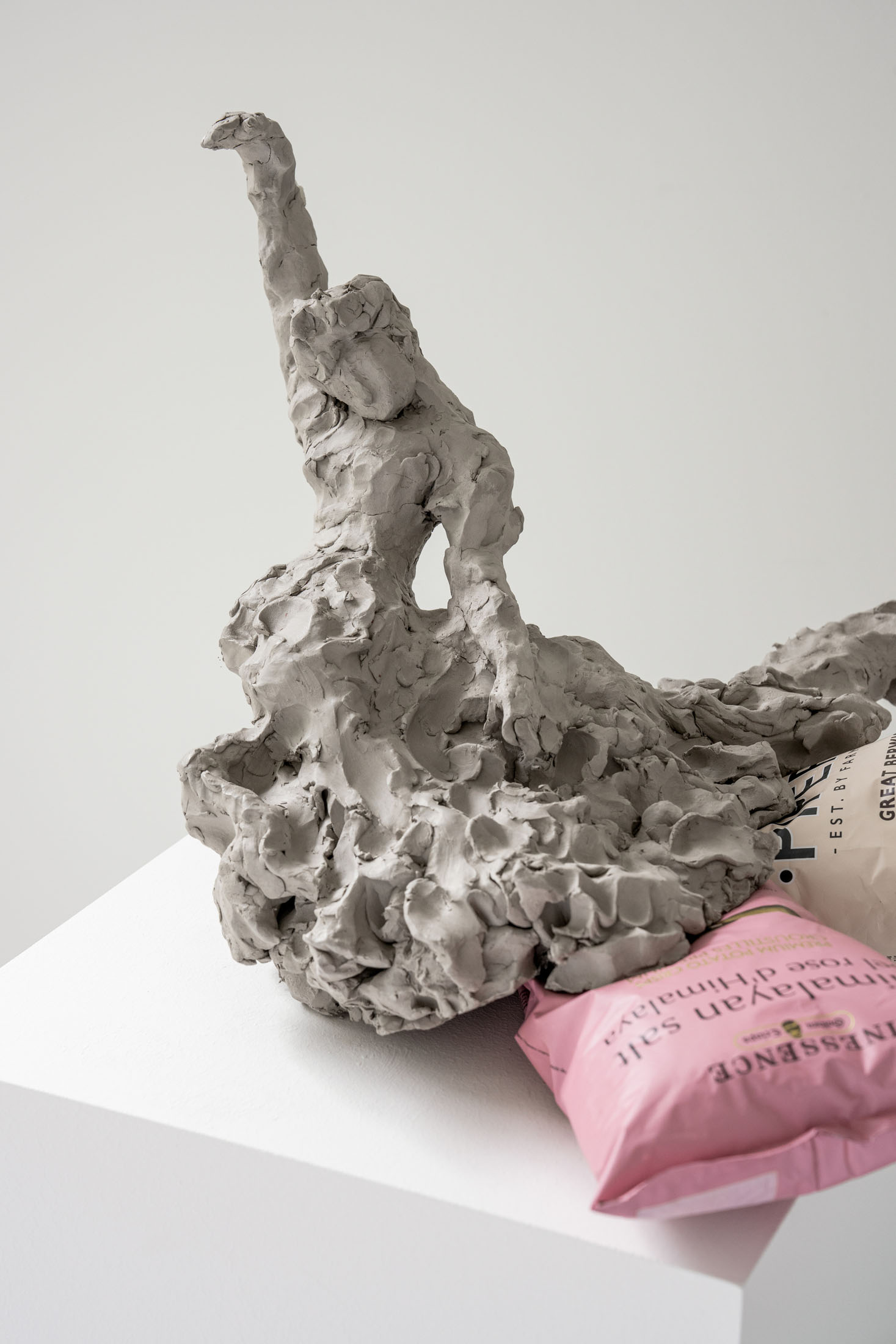

Decisions about purchases and social distinctions potentially associated with them are made even more tangible in the work featured in the Italics show. In the Fainter on posh crisps series, which was created for the exhibition, the variously inclined clay figures form assemblages in combination with a wide variety of crisps bags. In the United Kingdom, unconventionally flavoured snacks are referred to as ‘posh crisps’ in contrast to the tried-and-tested salt and vinegar variety originally associated with the working class. The flavours of ‘posh crisps’ themselves allude to exoticism and the lifestyles of the supposedly higher social classes, and include Pink Himalayan Salt, Asparagus, Balsamic and Truffle, for example. In 1979, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu stated in his essay, Distinction , (1) that the purchase of a product is never just an individual decision, but always also an expression of habitus, social field and the pursuit of distinction. Posh crisps thus combine taste that is both ‘discriminating’ (bourgeois with a focus on aesthetics, style, and exclusivity) and ‘pretentious’ (oriented towards social advancement, imitating more sophisticated styles and practices, in an often slightly exaggerated or apparently inauthentic manner, because not anchored in the consumer’s own social background). Whilst the target group for posh crisps includes the traditional upper class, they are also aimed at hipsters with a penchant for social advancement and members of the working class who want to treat themselves to something nice now and again.

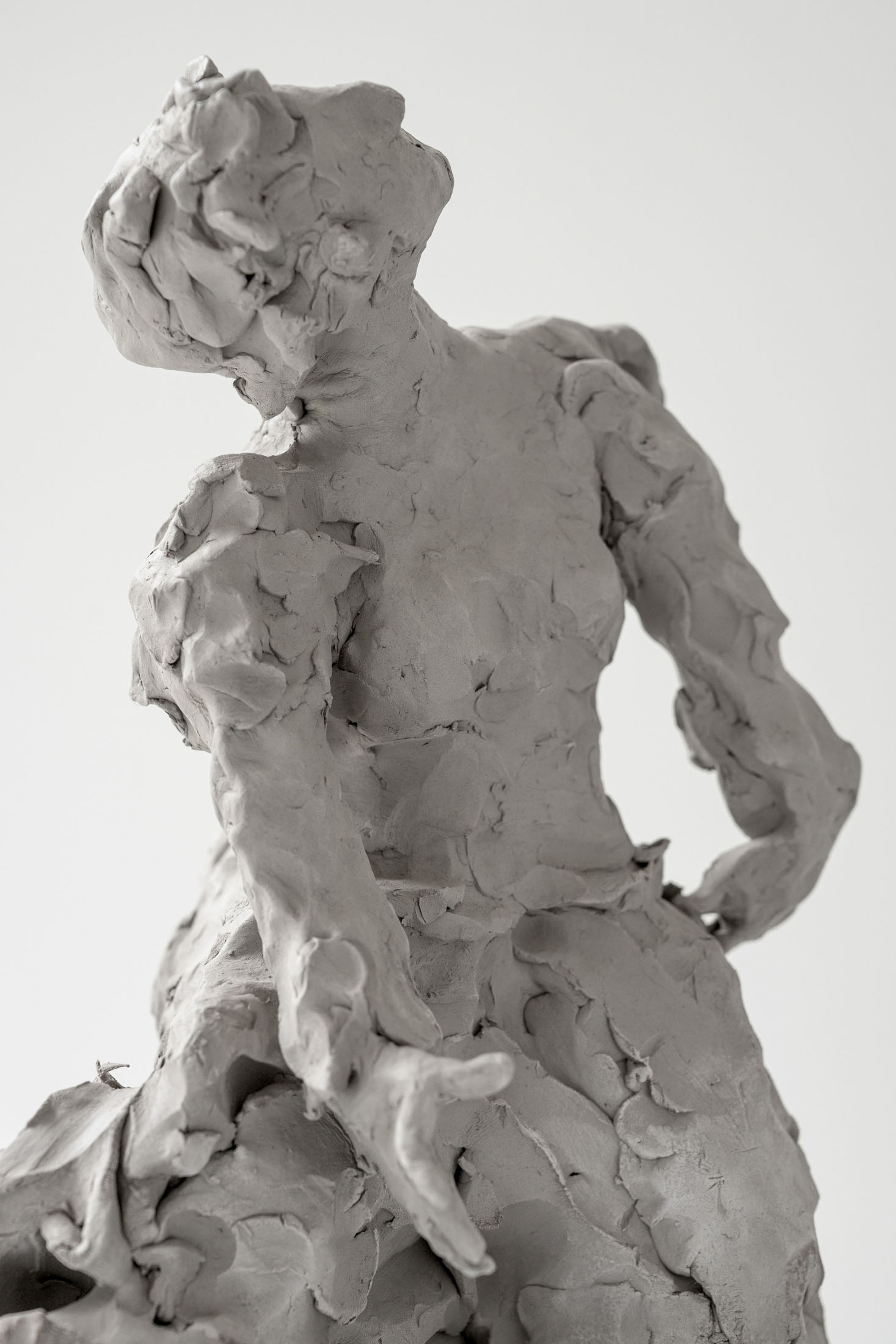

In Fainter on posh crisps, inflated crisp packets repeatedly amplify the exaggerated tectonic torsional moments created in the rotation of the figures, simultaneously having both a stabilising and destabilising effect. Compositionally, the inflated skirts also mirror the forms produced by the packets. Both types of voluminous inflation reinforce the drama inherent in the act of falling unconscious – a powerful gesture, which, when performed consciously and theatrically, ensures that all eyes are on it, whilst, at the same time, involving a withdrawal from the situation. The Fainter on posh crisps thus lay claim to as much space as the sculptural forms of the Domestic Tails. In the former series, Wermers also alludes to the claims to surrounding space in art history’s preoccupation with inclination and collapsing bodies, ranging from Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa, to the diagonals in Medardo Rosso and Auguste Rodin’s sculpture, to Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s tilted heads and Edward Steichen’s photography, which is full of inclined forms.

The philosopher, Adriana Cavarero (2), interprets the posture of inclining not only as a formal compositional principle, but also as an ethically ambivalent gesture. In Leonardo’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1503–19), it represents an everyday, albeit iconic, gesture of care, which one might contrast with the patriarchal verticality of works, such as Michelangelo’s David, or pyramidal compositions of figures signalling autonomy and power. The Virgin’s off-balanced posture here acts as a gesture that subverts systems dominated by erectness and hierarchical order. According to Cavarero, however, the gesture of inclining as a departure from one’s own central axis is not automatically the consequence of a predetermined action. Inclination, she argues, is a disposition – it can result in an act of care, but also in injury. In the case of Leonardo’s Virgin, it signifies affection, in Medea’s case it represents violence.

Wermers expands this concept to include questions of body, space and power. Italics subversively thematises the classical verticality of sculpture, which is often connoted as masculine and allied with connotations of social distinction. In her series, Domestic Tails, which takes the form of tails in faux fur unspooling from hose and cable reels, sculptural lines run across rooms and cross thresholds. They make reference to invisible infrastructures, such as electricity cables or water pipes, but also to spatial hierarchies that domestic animals, in particular, find easy to challenge. The inclination of such animals is to reach out into space – here they are represented as tails, which stand for connections made between differing spaces and times, and for the possibility of moving beyond clear boundaries.

In Fainter on posh crisps, in contrast, sculptures of female figures in lavish historical dresses are frozen at the moment of fainting, and inclining becomes a metaphor for the exhausted body, suspended between erectness and collapse, between verticality and horizontality. They are figures in an ‘in-between’ state, inclined and diagonal in orientation, thus embodying the ambivalent attitude as described by Cavarero: a physical and ethical disposition making visible both dependency and vulnerability, as well as resistance and subversion.

Wermers links these aspects of inclining to social issues of visibility and invisibility, and to invisible social hierarchies. These include access policies to historical aristocratic building types, for example, rooms invisible to guests, but easily accessible to house pets. This was the inspiration for Domestic Tails – tails with bodies absent; repetitive, hidden work as inscribed in the hand-sewn; and invisible social forces provoking the gesture of powerlessness of the Fainter on posh crisps.

Spatially, these hierarchies unfold within the constellation of absence and presence that pervades Wermers’s entire oeuvre. The powerlessness thematised in Fainter on posh crisps also involves a withdrawal linked to dramatic gestures that make claim to space, acts that are often performed only in the presence of an audience. The voluminous dresses worn by the figures, which signified social status during the Rococo and Baroque eras, here create both presence and distance, and thus the displacement of other bodies. The Domestic Tails series, which structure the space with their presence, simultaneously represent traces of obviously absent bodies.

With these themes in mind, Wermers has been examining the structural and physical hierarchies of domestic and urban space in relationship to bodies – both present and absent – for over two decades, linking these analyses with citations from art history and everyday culture. As philosopher Elizabeth Grosz describes in her essay, ‘Bodies-Cities’: “Bodies and cities are mutually defining: the city provides the context in which social rules regarding the body are inscribed and made to count, while bodies are the means through which cities are lived and experienced. The absent body, or the body’s limits, is what makes space possible.” (3)

For Wermers, inclination thus becomes a multi-layered principle allowing her to question both formal systems and social and political structures. As in Cavarero’s work, it simultaneously permits her to keep open the ethical tensions between caring and violence, and affection and exhaustion.

Text: Anna-Catharina Gebbers (translated from German)