Artist: Nicolás Lamas

Exhibition title: Thinking About Things That Are Thinking

Venue: Meessen De Clercq, Brussels, Belgium

Date: October 27 – December 16, 2023

Photography: Alice Pallot / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Meessen De Clercq, Brussels

Thinking about Things That Are Thinking is the fifth exhibition at the gallery by Nicolás Lamas (born 1980). With this open-ended title, the Peruvian artist presents a series of new works that showcase the breadth of his artistic approach and the constant interaction between the different fields that he explores. Recovered objects, superimposed images, deviations and oblique trajectories, digital contaminations, various materials assembled to show the frailness of human nature on the one hand and staggering technological progress on the other, propelling humanity towards an unknown future. Lamas’ approach is based on the interrelation between ideas, forms and materials. Working on a system that embraces chance, accidents and exceptions, he deciphers the world by establishing connections between science (geology, biology, etc.) and our systems of interpreting the world (anthropology, archaeology, paleontology, geopolitics).

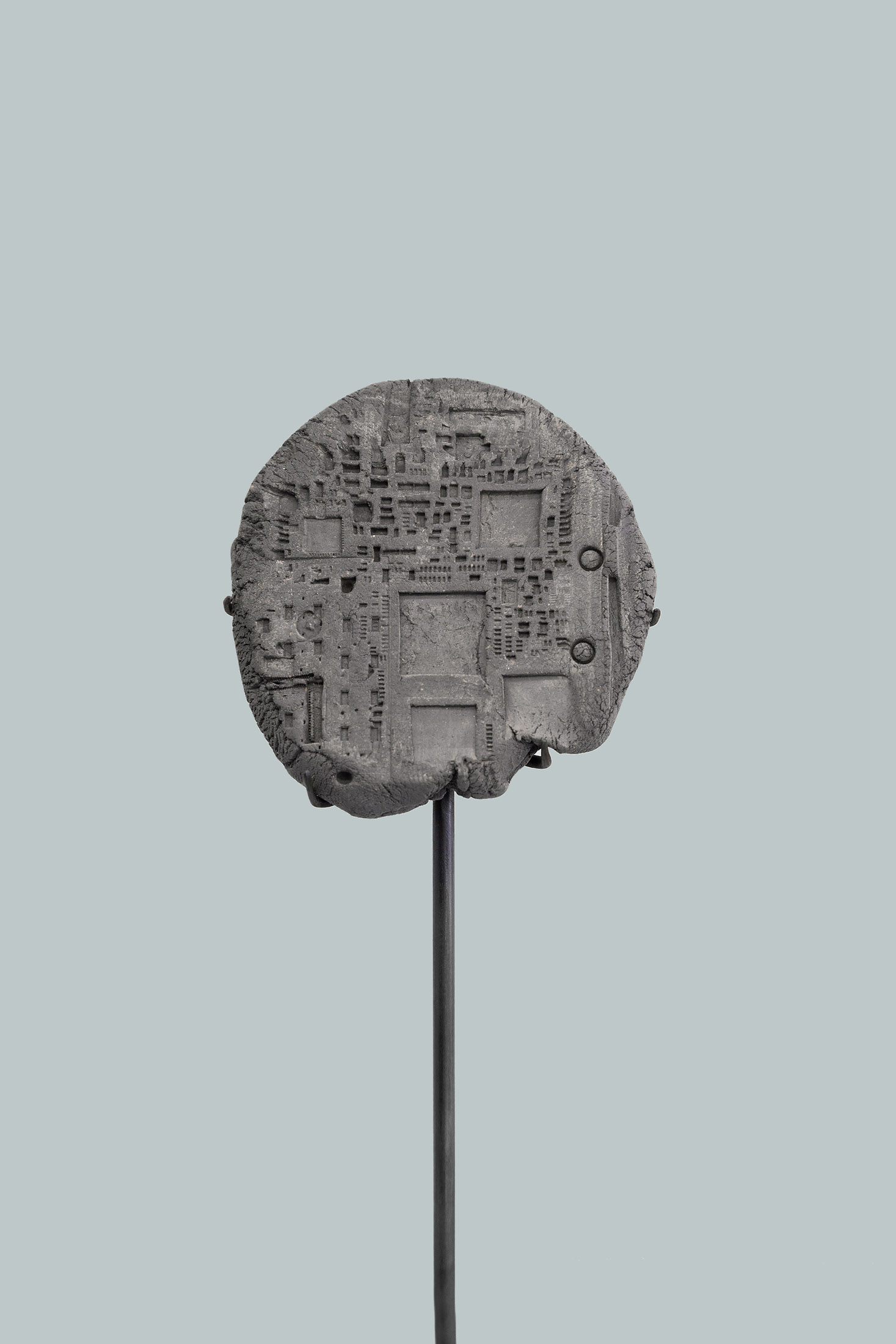

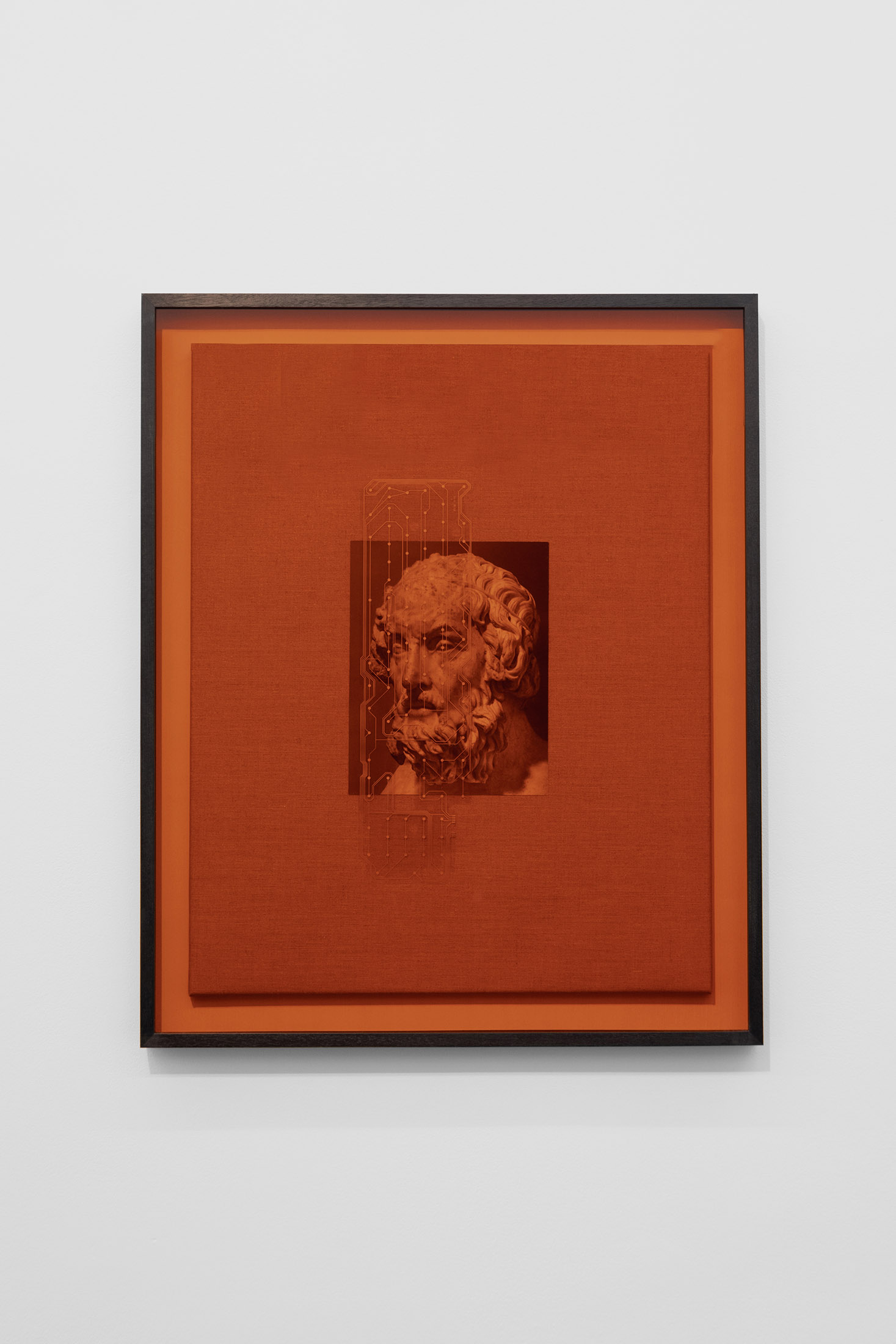

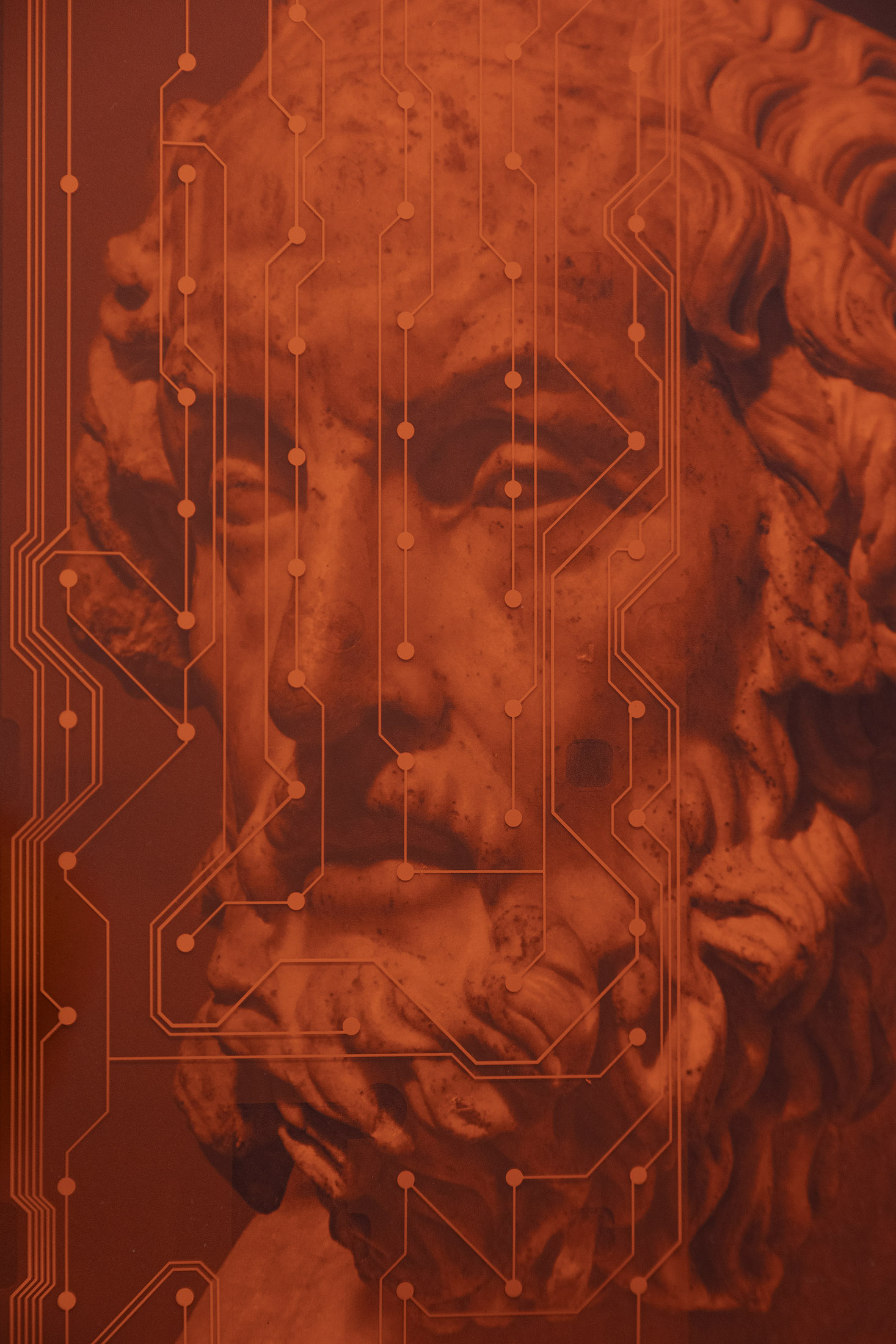

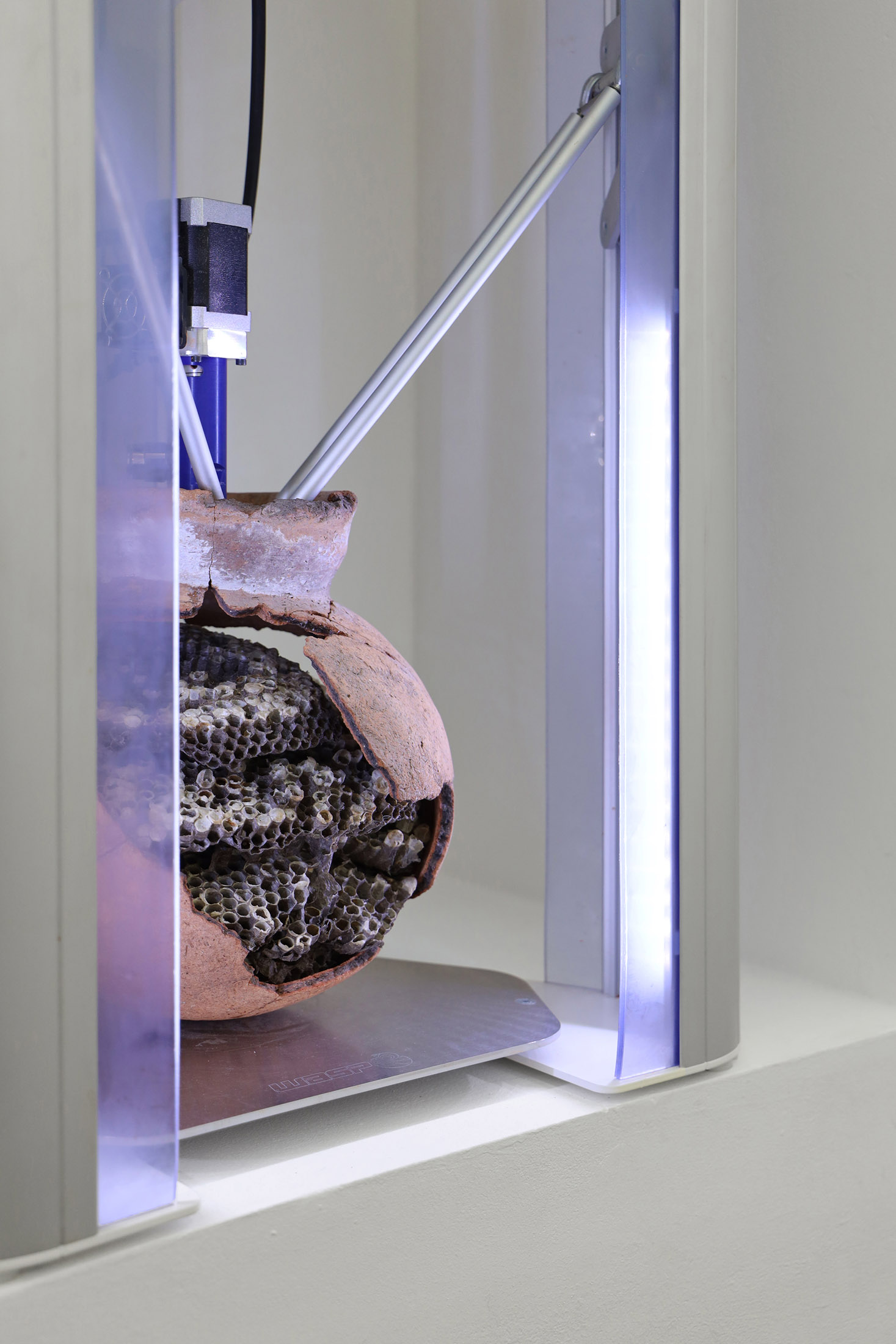

The room on the right shows us his constant interest in reconstructing the past by collecting and reassembling fragments and information, recreated through his personal prism. A portrait of Homer paired with part of a computer keyboard stands across from the Letters to the Future, a series of seven clay tablets, in explicit reference to the Sumerian cuneiform inscriptions that are the first traces – the first appearances, one might say – of writing that have reached us. But Lamas performs a major shift, since the markings in the clay are made by electronic cards – humanity’s most recent language – opening out into the intangible realm of digital information. Linking past and present through multiple connections, Lamas explores the intersections of history, language and innovation. Set in an alcove, the combination of a 3D printer, a wasp’s nest and a clay vase, refers as much to modern production techniques and the complexities of life, as it does to a traditional craft stretching back to Neolithic times.

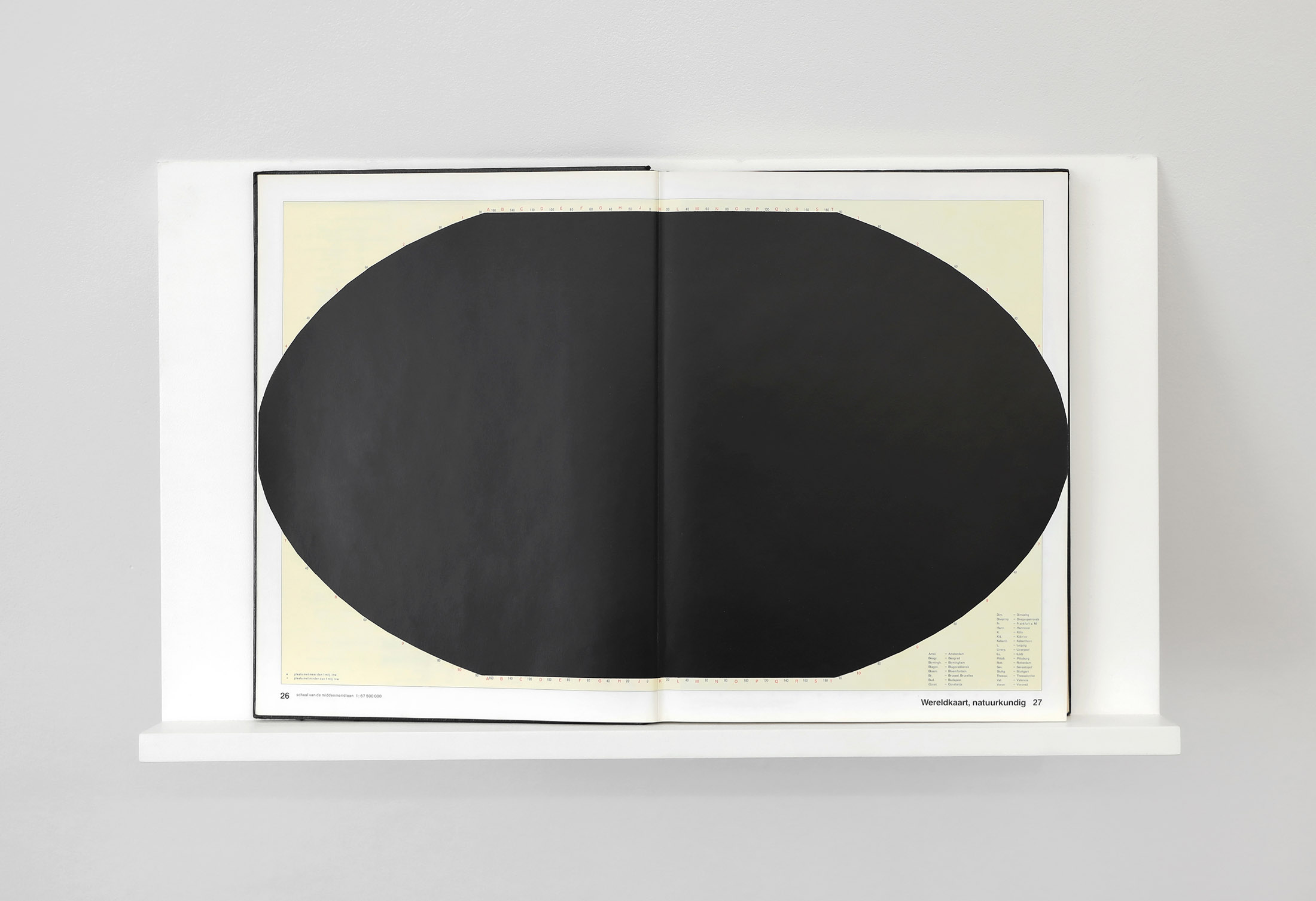

The work Three different ways to understand a space is a print of a view of the cosmos that has failed. The visitor discovers a cosmic reproduction, followed by a cryptic geometric code before opening out onto a final, completely blank segment, a kind of silent witness to the interstellar void. The imperfection of the print is a reminder of the consistent failings in our understanding of the origin of the Universe. Human intentions are sometimes thwarted by technological limitations or errors. Close by, an atlas partly painted black leads us down an impasse: a saturated world, overly narrated, too much discussed? Or a world on the brink of an apocalypse and the disappearance of life itself? The interpretation remains open.

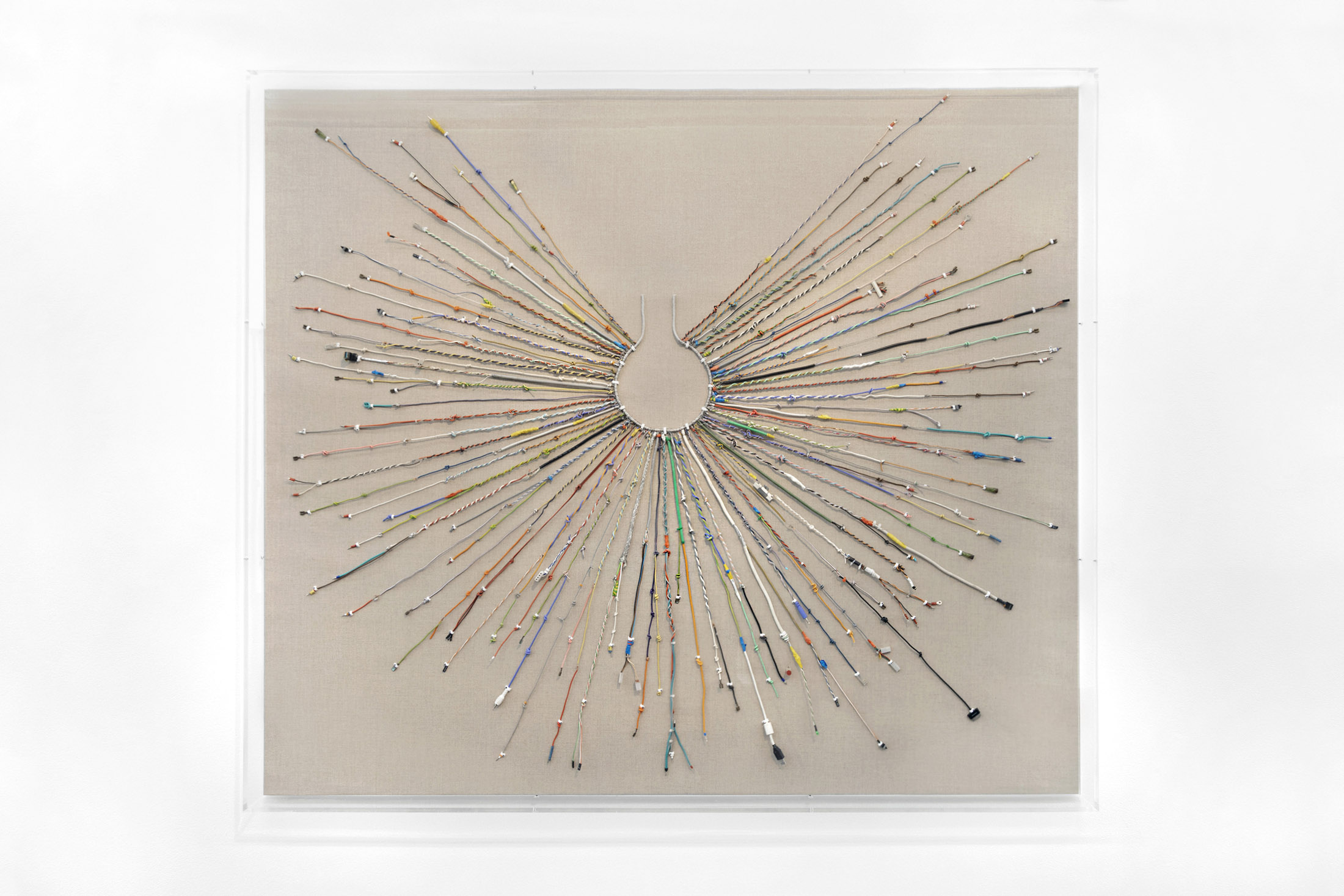

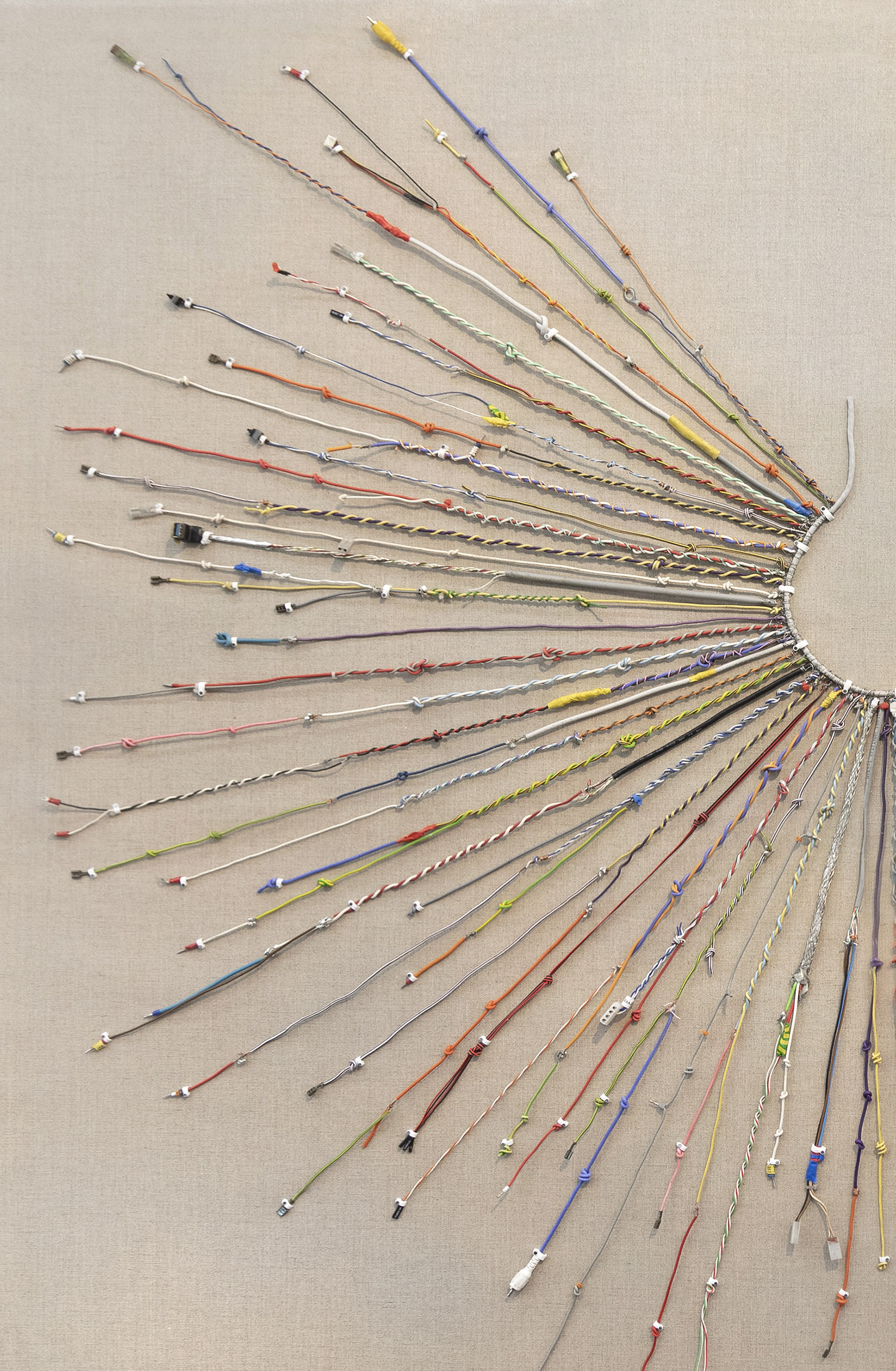

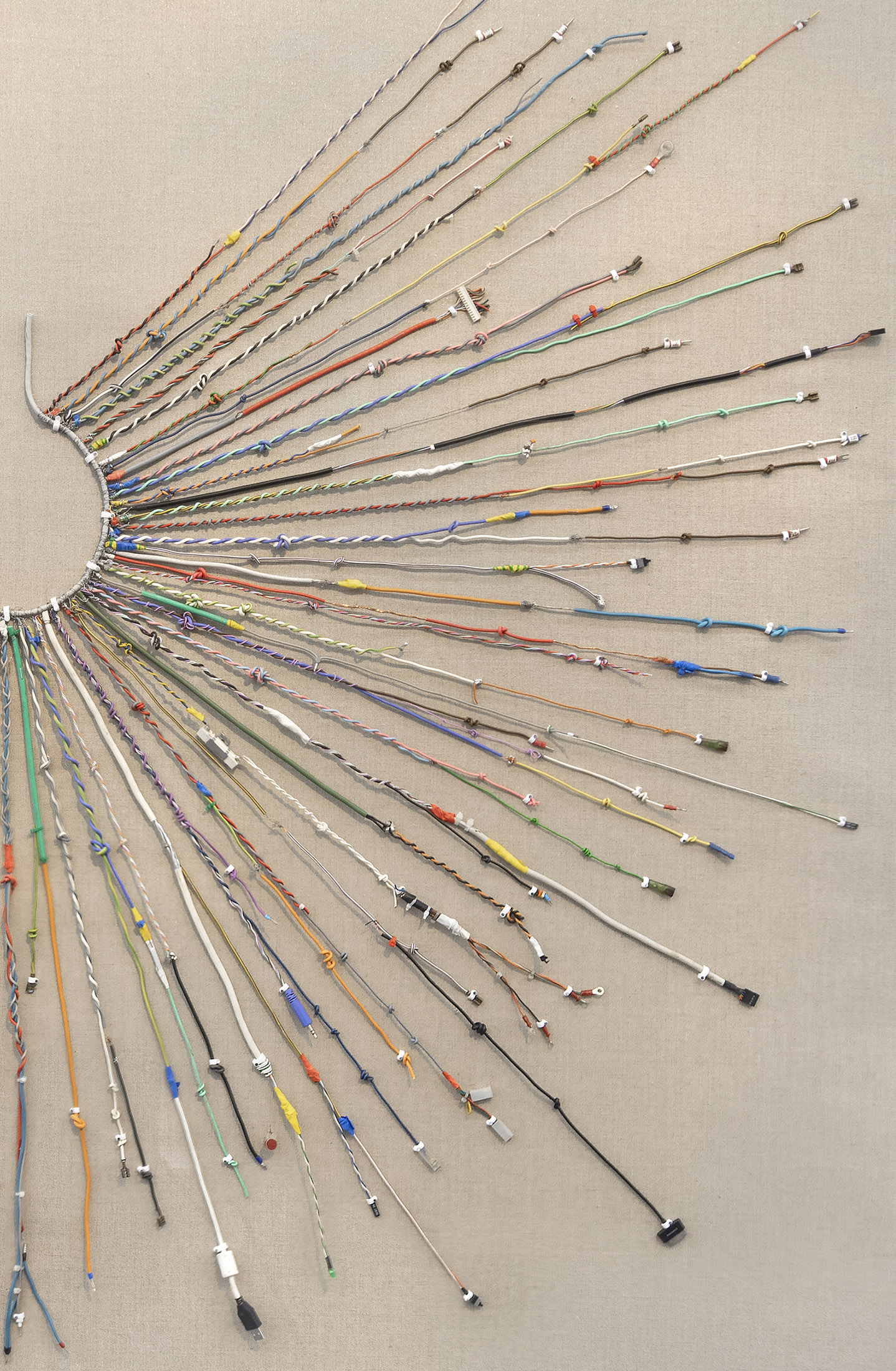

Entering the room to the left, the visitor is confronted with Extended mind, an unusual reconstruction of an Inca quipu – made out of a meticulous assembly of electrical cables and wires – referring to the accounting system ingeniously devised by the Incas 4,000 years ago. The arrangement of the knots, the colors and the lengths of the cords made it possible to record, read and remember information that was important to the life of the city. By using electric cables, Lamas establishes a parallel between the innovations that shape a society and certain fundamental discoveries in physics (the conductivity of copper, insulating plastics, etc.), while also reminding us of our current dependence on connectivity and the transmission of information.

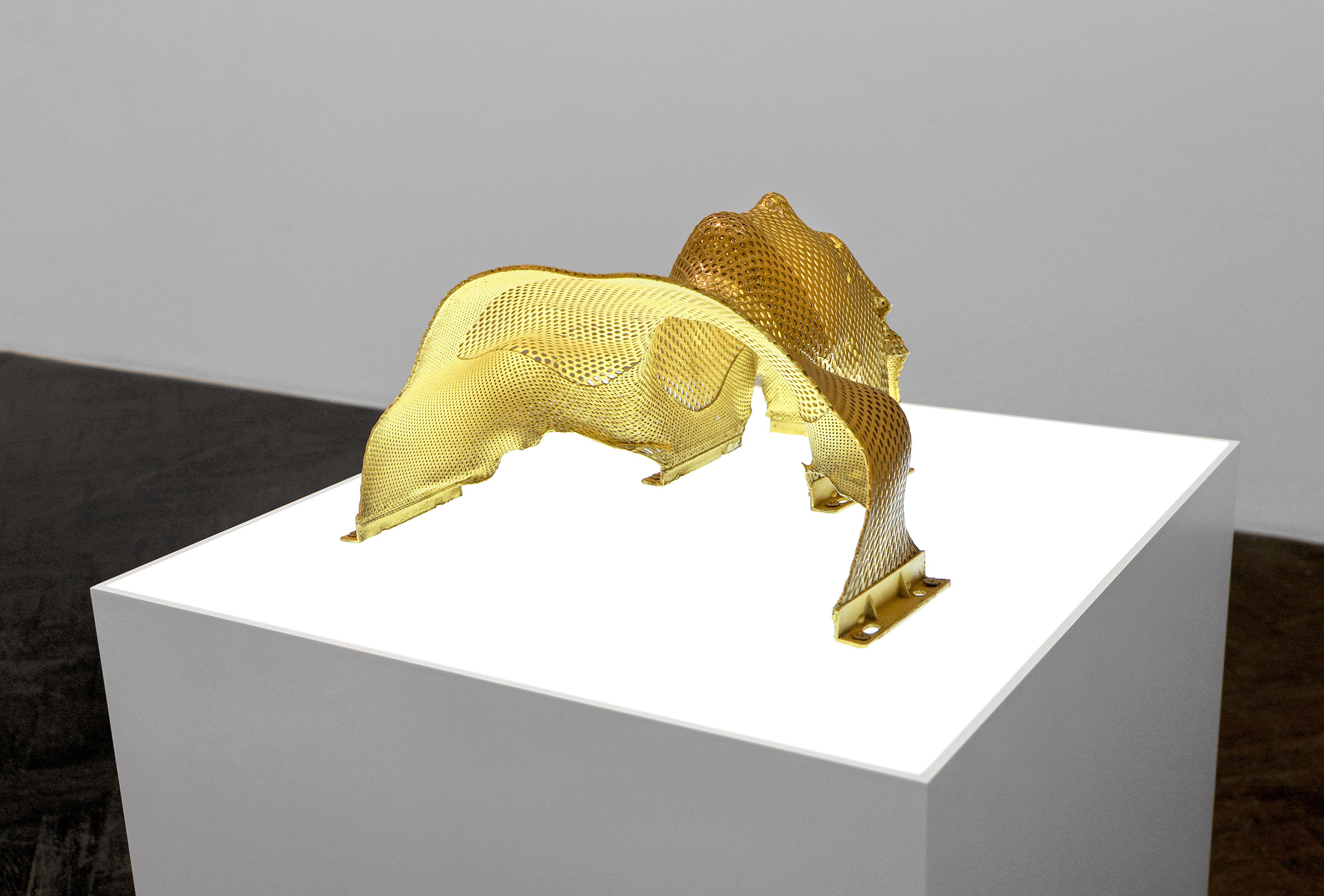

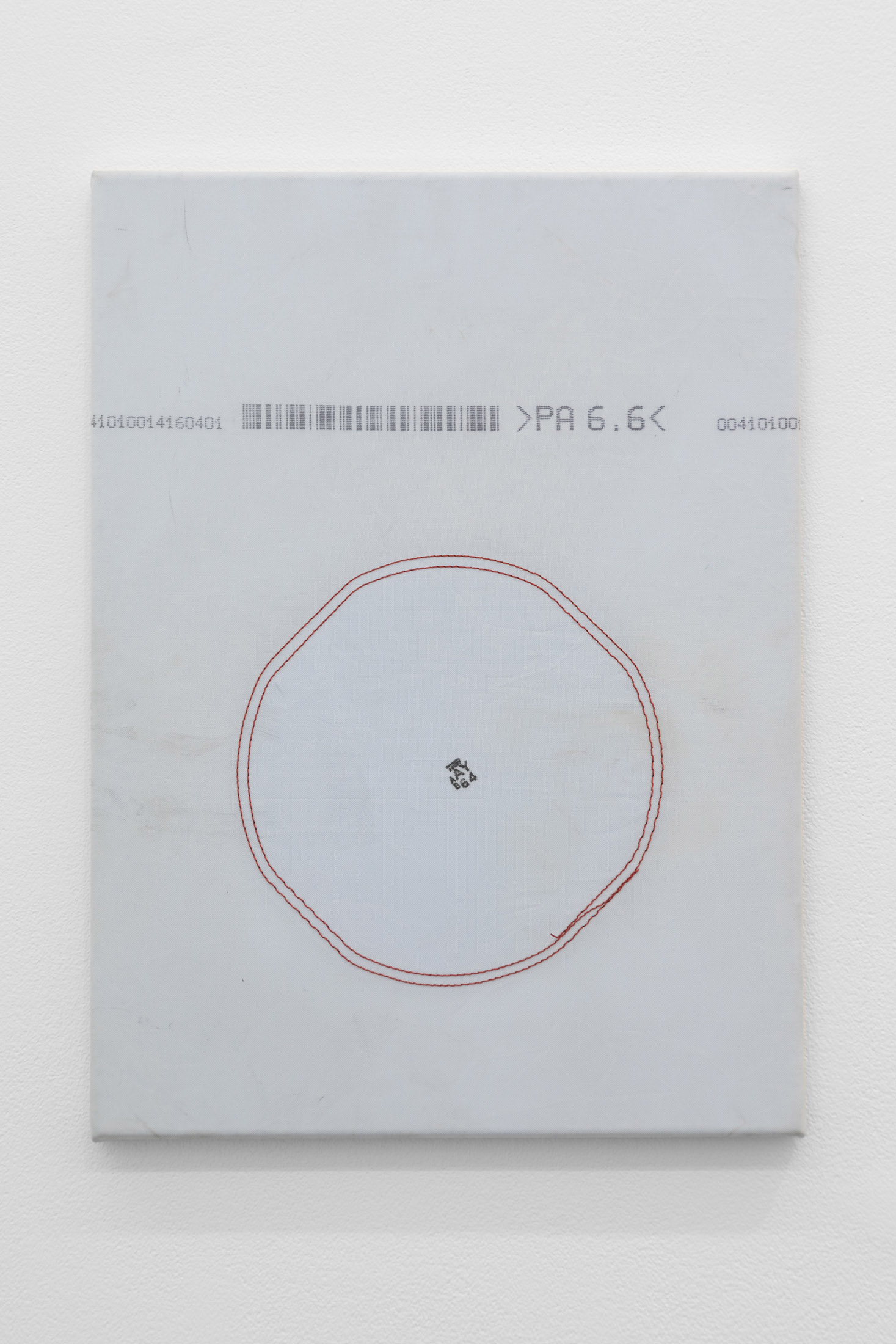

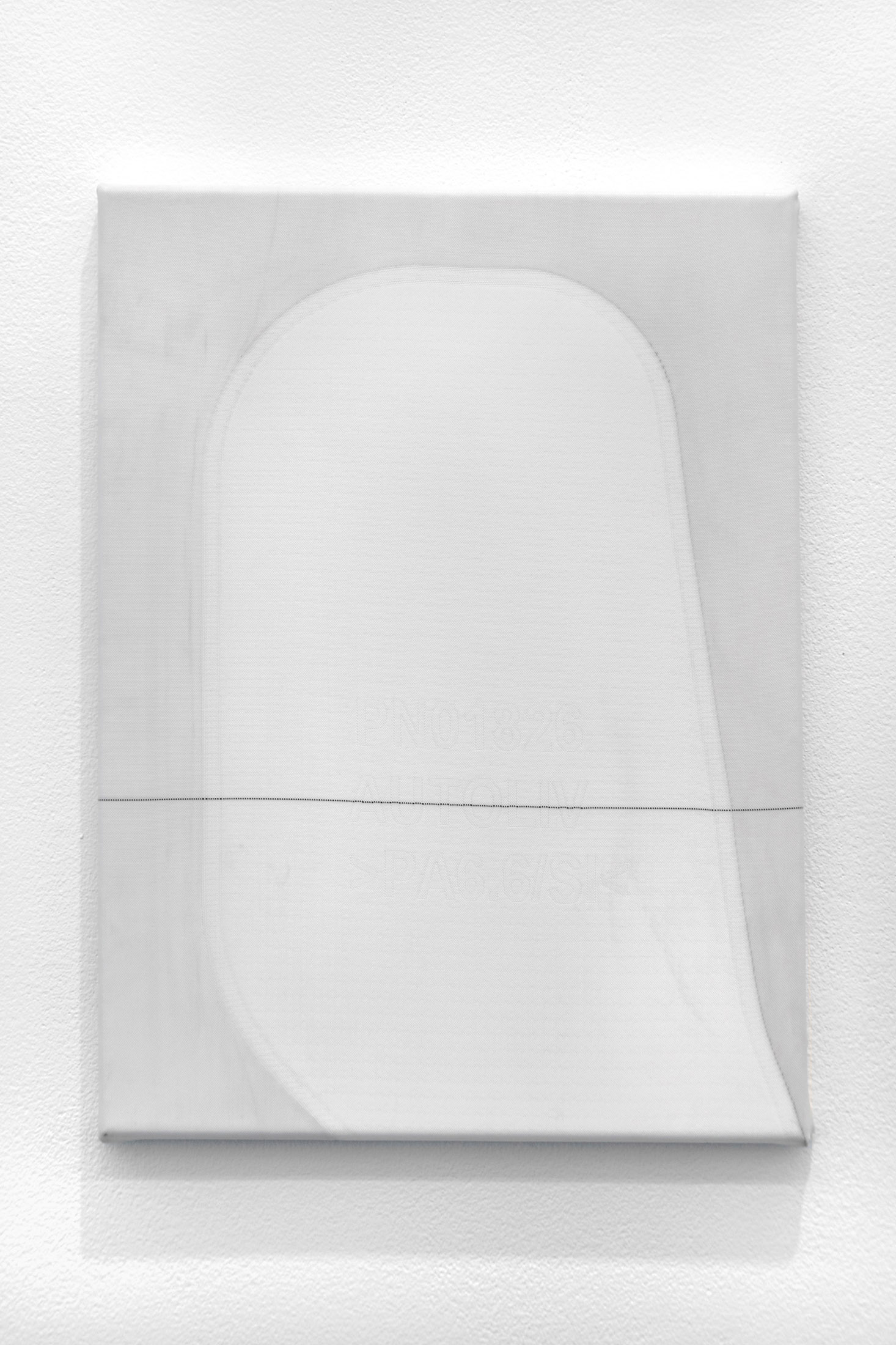

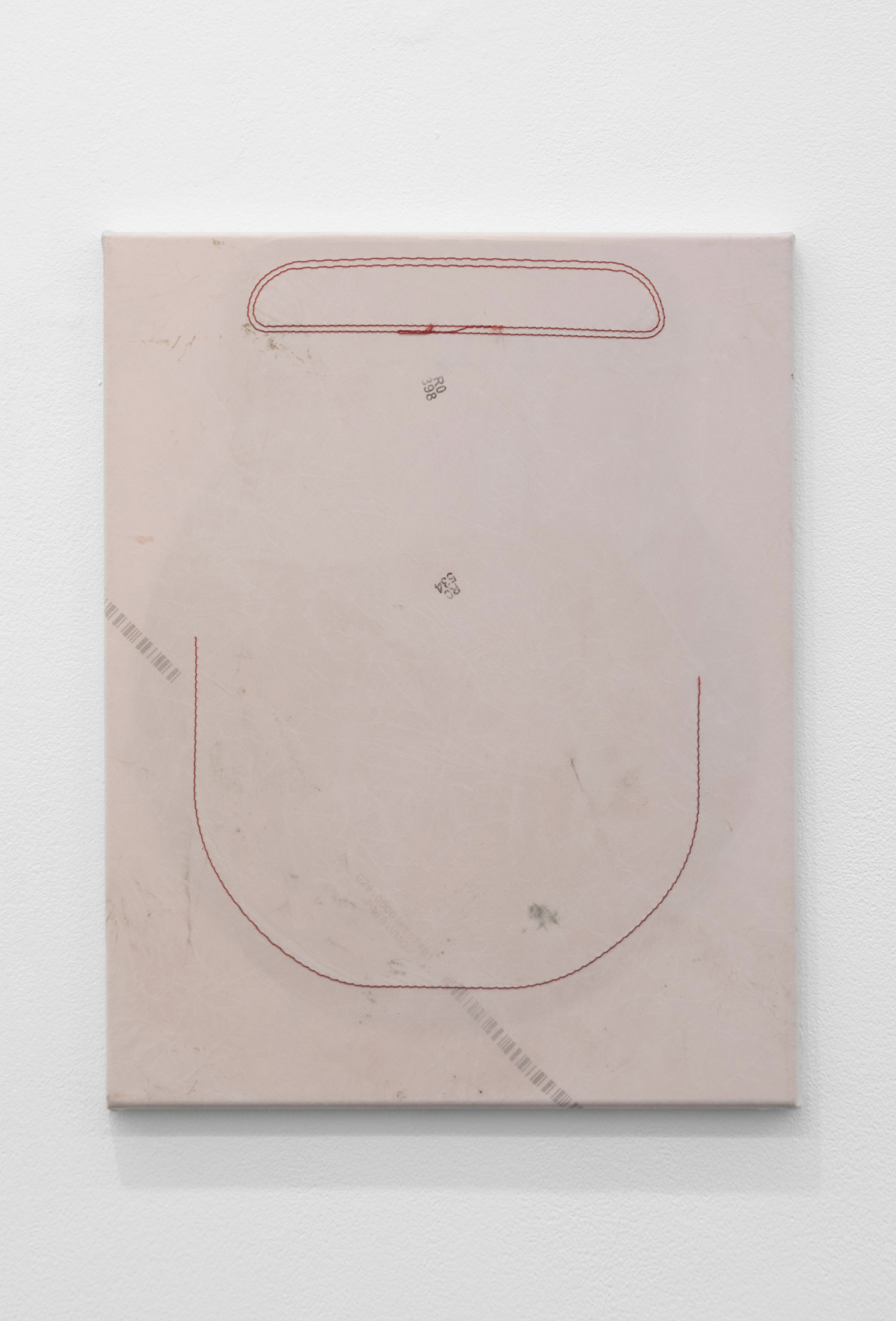

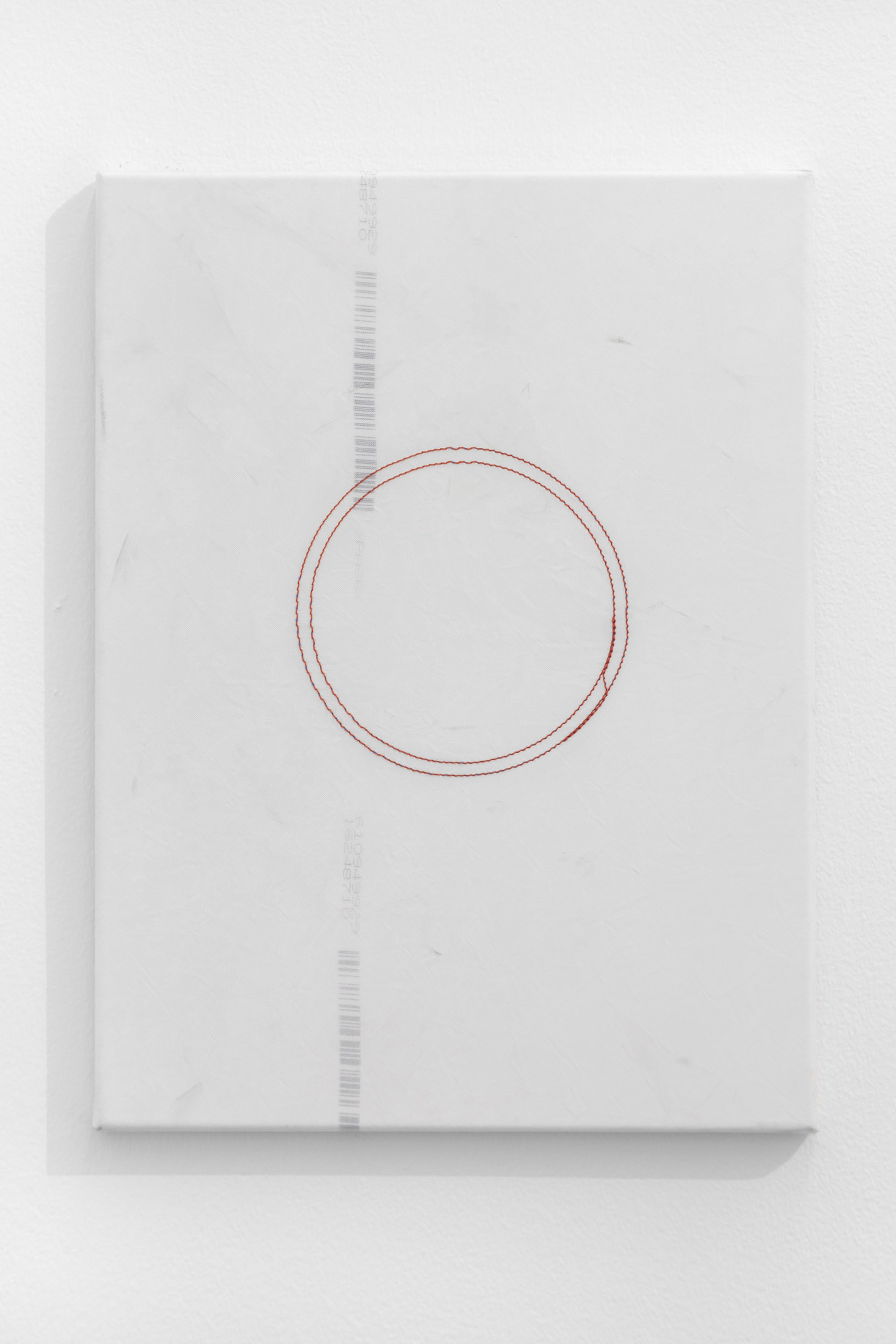

Liminal embodiment offers another parallel between the ancient and the modern world, with a mask placed on a light box, reminiscent of ancient Egyptian funerary masks. Used in cancer treatment, this mask has been electroplated with gold, giving it a new aura and underlining the analogy with ancient Egypt. It’s interesting to note that scientists are increasingly using medical applications to scan, understand and preserve the integrity of fragile findings. In counterpoint, the paintings on the wall, entitled Impact Zone, are made from airbags, salvaged from crashed cars and stretched over a frame. The sobriety of the canvases reflects the vulnerability of the human body, while opening up a reflection on abstract painting.

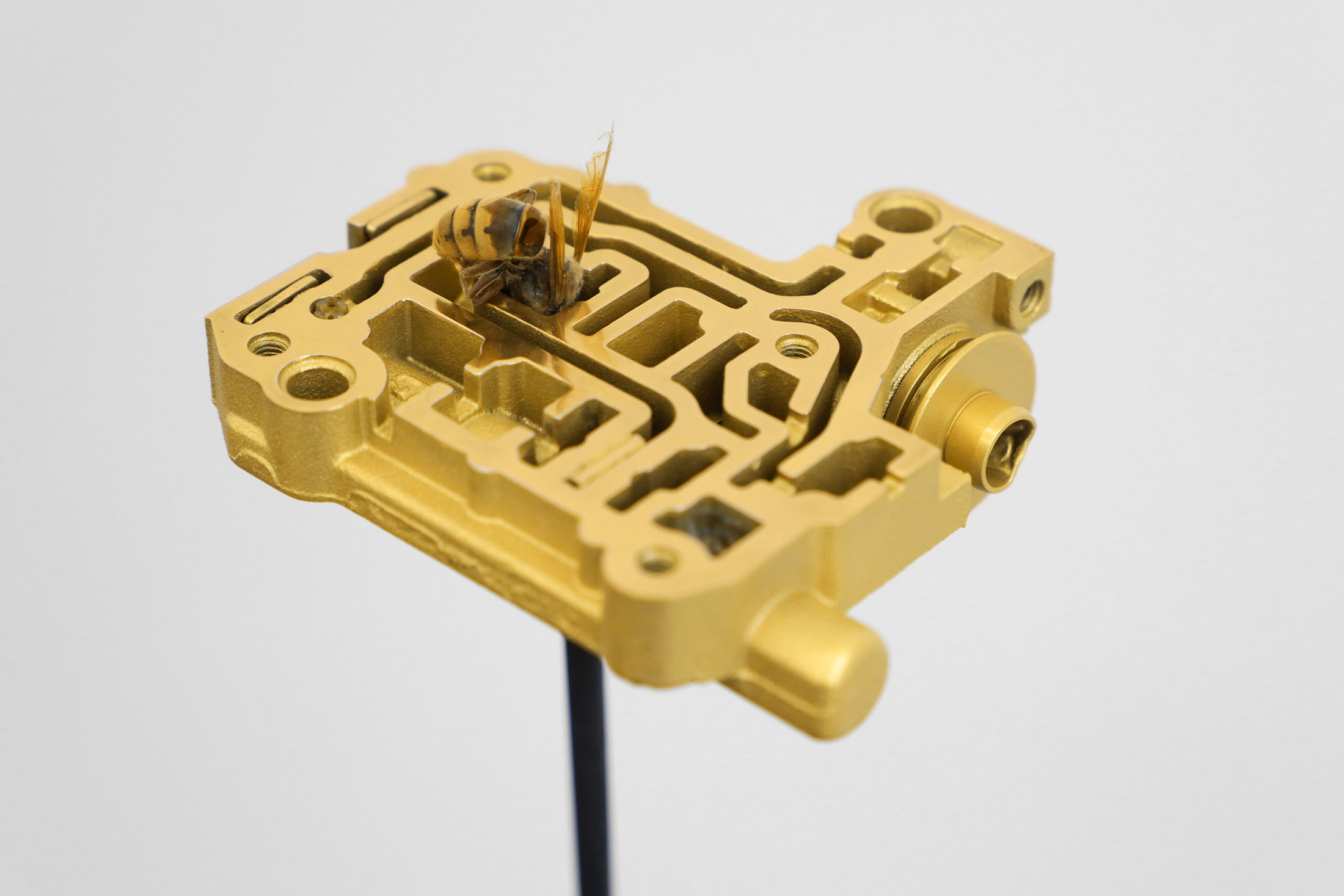

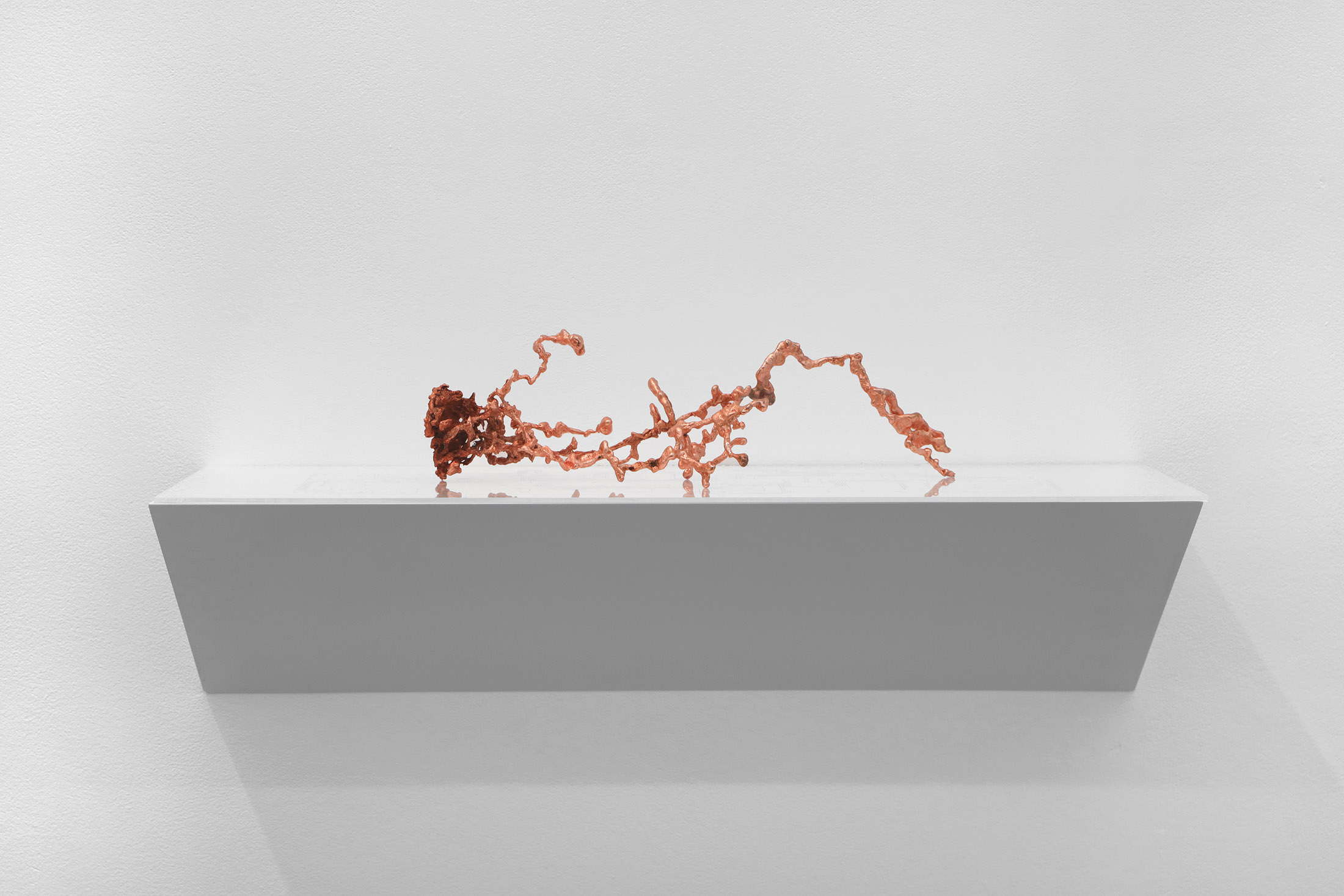

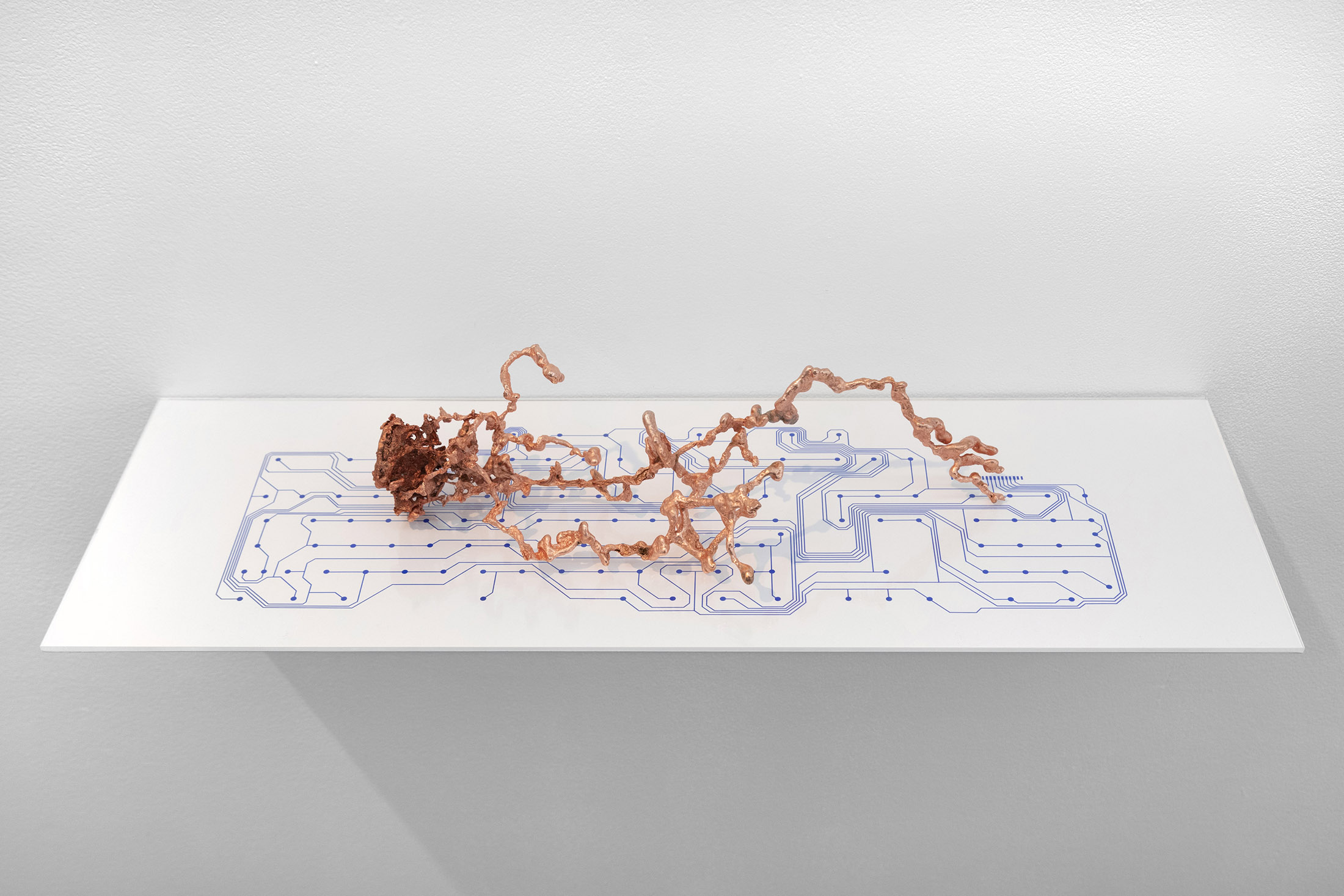

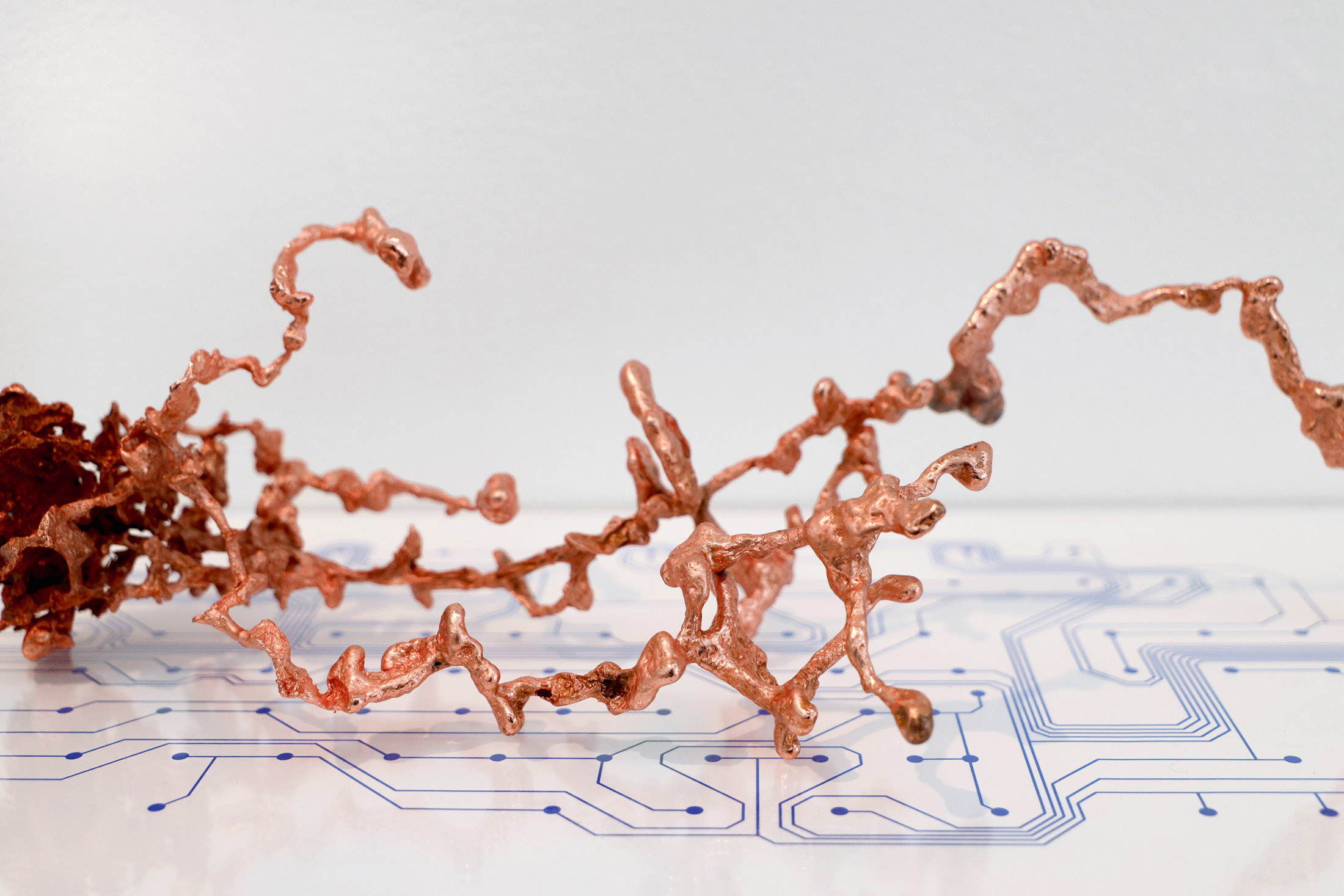

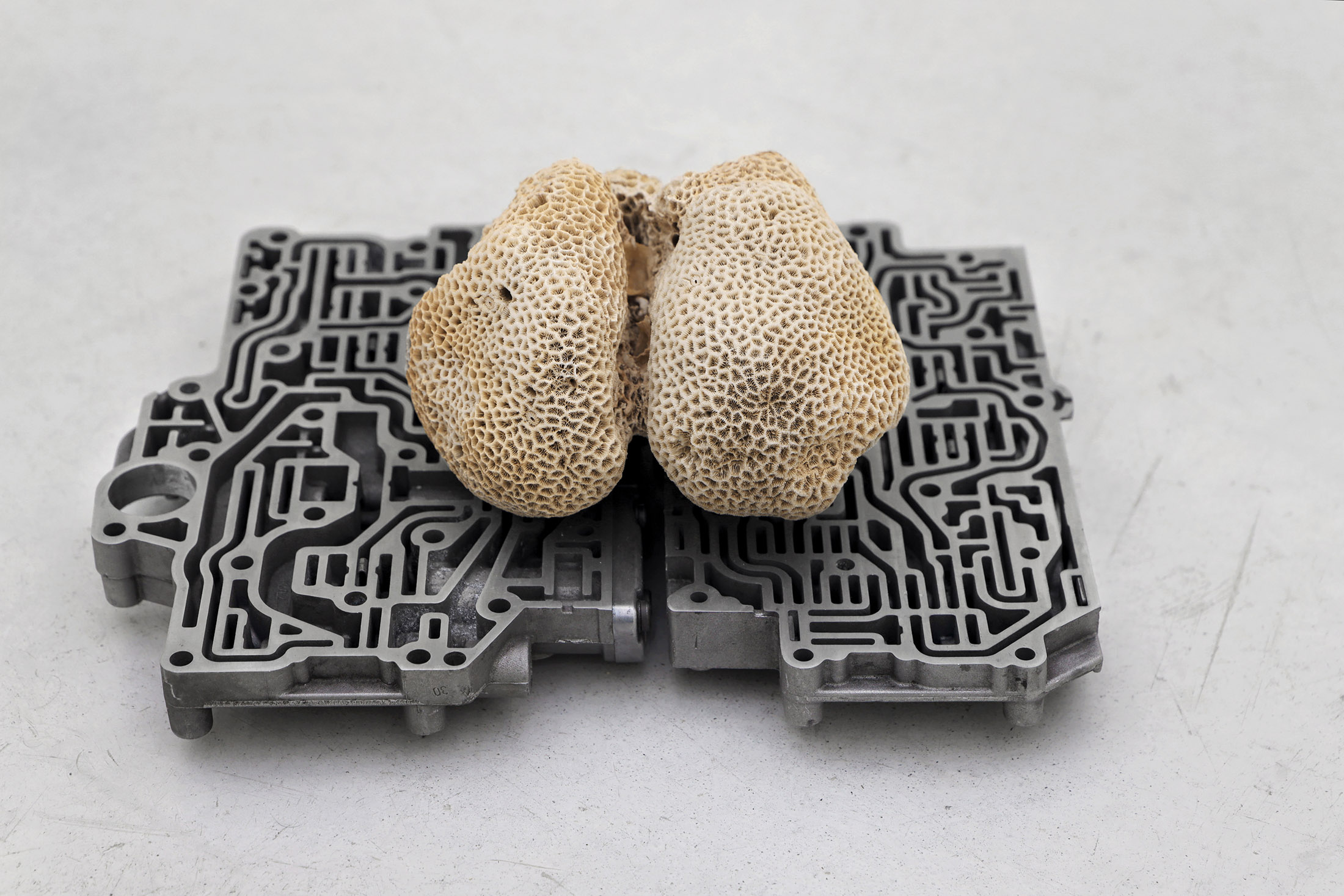

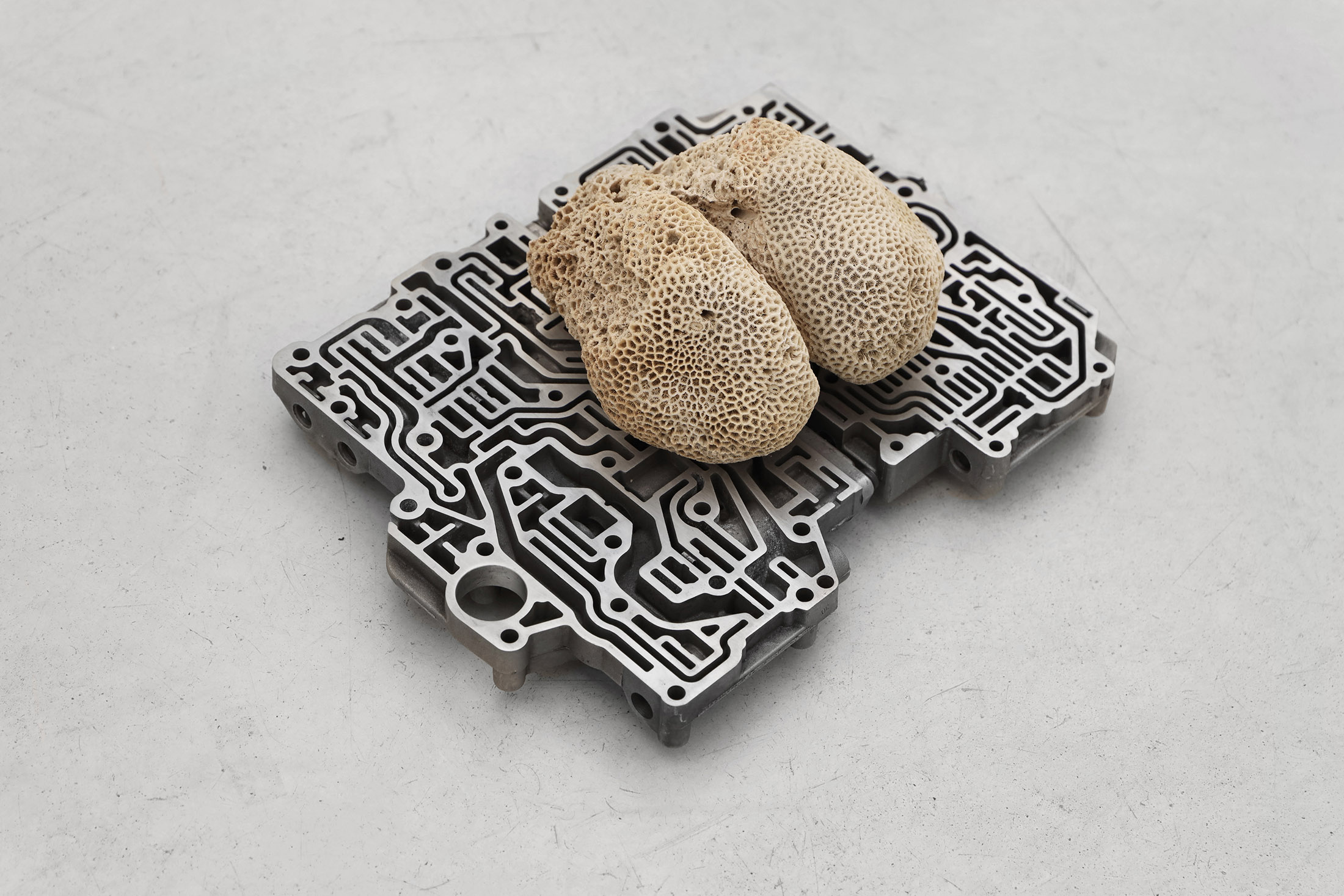

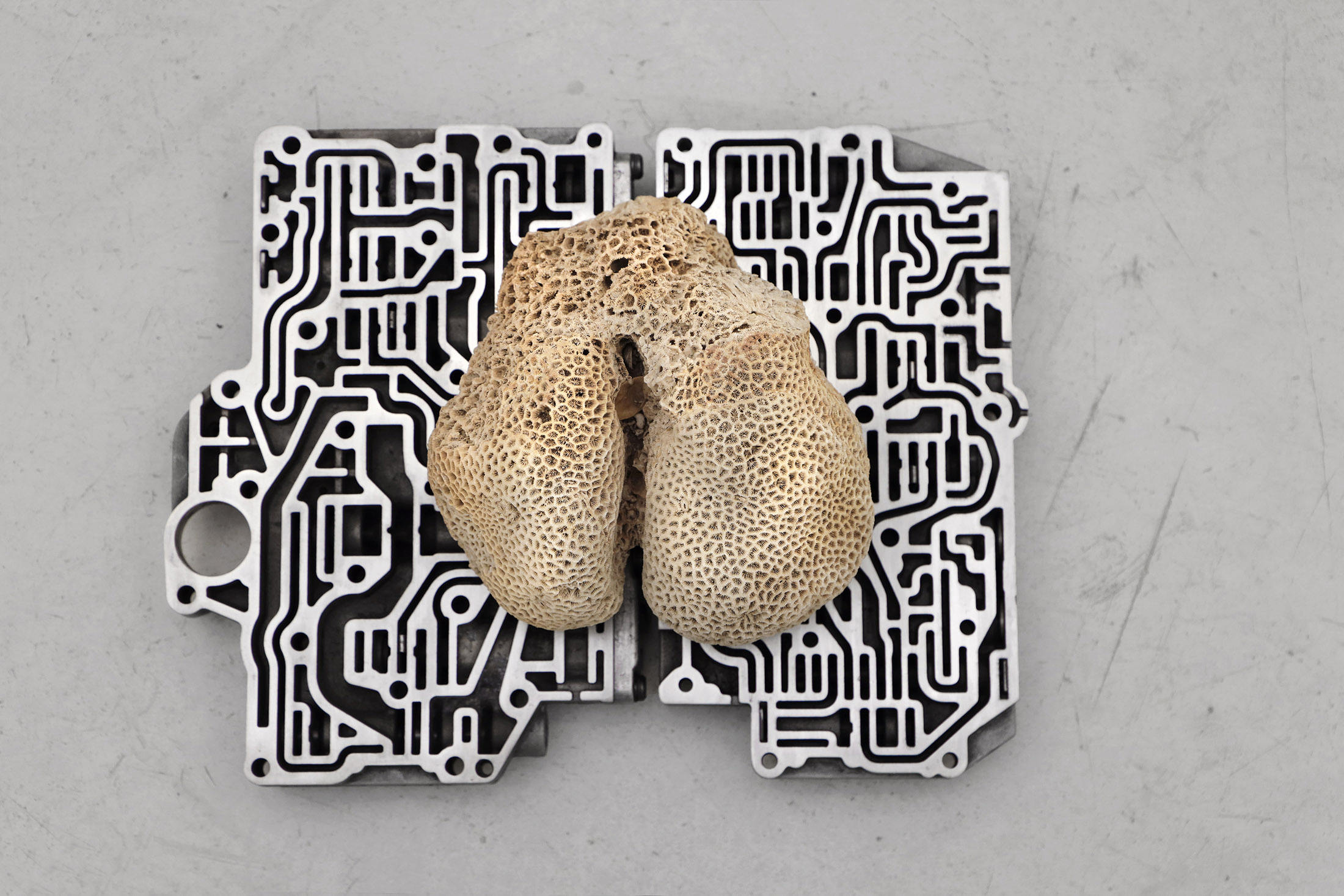

While dissecting the constituent parts of a car, Lamas also found a transmission valve, which he linked up to an encephalon-shaped coral (brain coral). One of the most important components in a car’s automatic transmission system is here linked with an endangered form of life. These two elements, both part of a wider system, invoke flux, interconnection and adaptability. With a copper cast of an anthill and its galleries, resting on an impression of an electrical circuit, Spinal cord colony is a work that initially appears more cryptic. With its complex subterranean architecture, doesn’t this network echo the human nervous system and its fascinating branches?

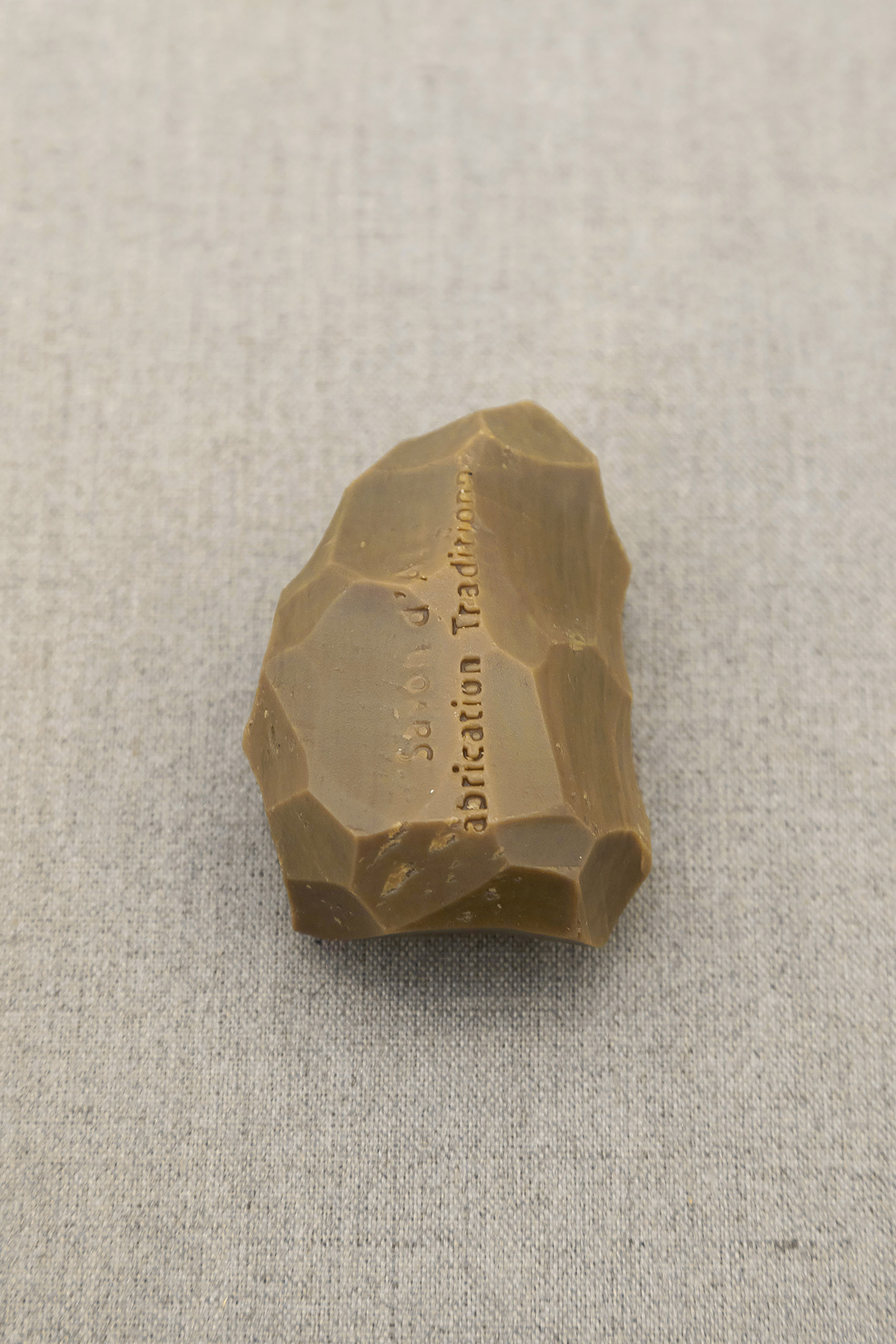

In the back room, several references to the emergence of Homo sapiens interact in subtle echo. In a structure originally used to house computer servers, Lamas has set a fragment of a wasp’s nest inside the reproduction of the fossilized skull of a hominid species who lived 3.5 million years ago. This bronze work offers a beautiful analogy between the organized society of wasps (particularly their nest building) and the amazing evolution of the human brain over time. Lamas works like an archaeologist, exploring, collecting and sorting objects and images found in different places, linking them together using a logic that allows an alternative reading of reality. A vein of humor also runs through his work, as in the display case containing a series of Paleolithic flints replicated in soap and shaped by hand in vibrant colors. Despite our best efforts to preserve the past, the passage of time transforms everything. His work is also marked by an iconoclastic approach. In Ways to disappear, he rubs and strips down a canvas bought at a flea market, yet preserves some visual traces. Beneath this act of erasure, he reveals another reality, both aesthetic and conceptual. The remaining fragments become gateways to the past, echoing forgotten histories (who originally painted this picture? what did it represent?).

Moving boundaries is also about fragments. Relishing accidental discoveries, Lamas picked up a broken plastic map of Europe, thrown on the street. Reassembled, the two main parts show the silhouette of an Europe in ruins, somehow still standing. The artist cast it in bronze, then covered it in gold. One side is shiny and the other is matte, both reflected in a mirror, itself set on a concrete base. It’s all a question of reflection as we ponder current challenges and the role of Europe (migratory flows, Ukraine, Brexit…). The map is an abstraction of reality. Illusions guide our perceptions. This is underlined by the power of the digital, with a burnt-out iPhone shown in tandem with a plant fossil several million years old… The phone’s memory card (tomorrow’s fossil) is weighed against the earth’s petrified memory, silently imprinted in geological, supra-human time.

Never before in the history of humankind have so many instruments and means of changing the course of life been at humanity’s disposal and control. Science is constantly advancing, in leaps great and small, bringing with it new horizons, new forks in the road that will have an inevitable impact on human life. Our species remains fragile, even though we might think otherwise. The depredations it inflicts on the earth system pose a serious threat, as we see in the photo diptych Boundaries of Existence. The notion of time, the occupation of space, artificial territories, the manipulation of bodies, plant and animal species, the status of languages and civilizations – everything is changing at a pace never seen before.

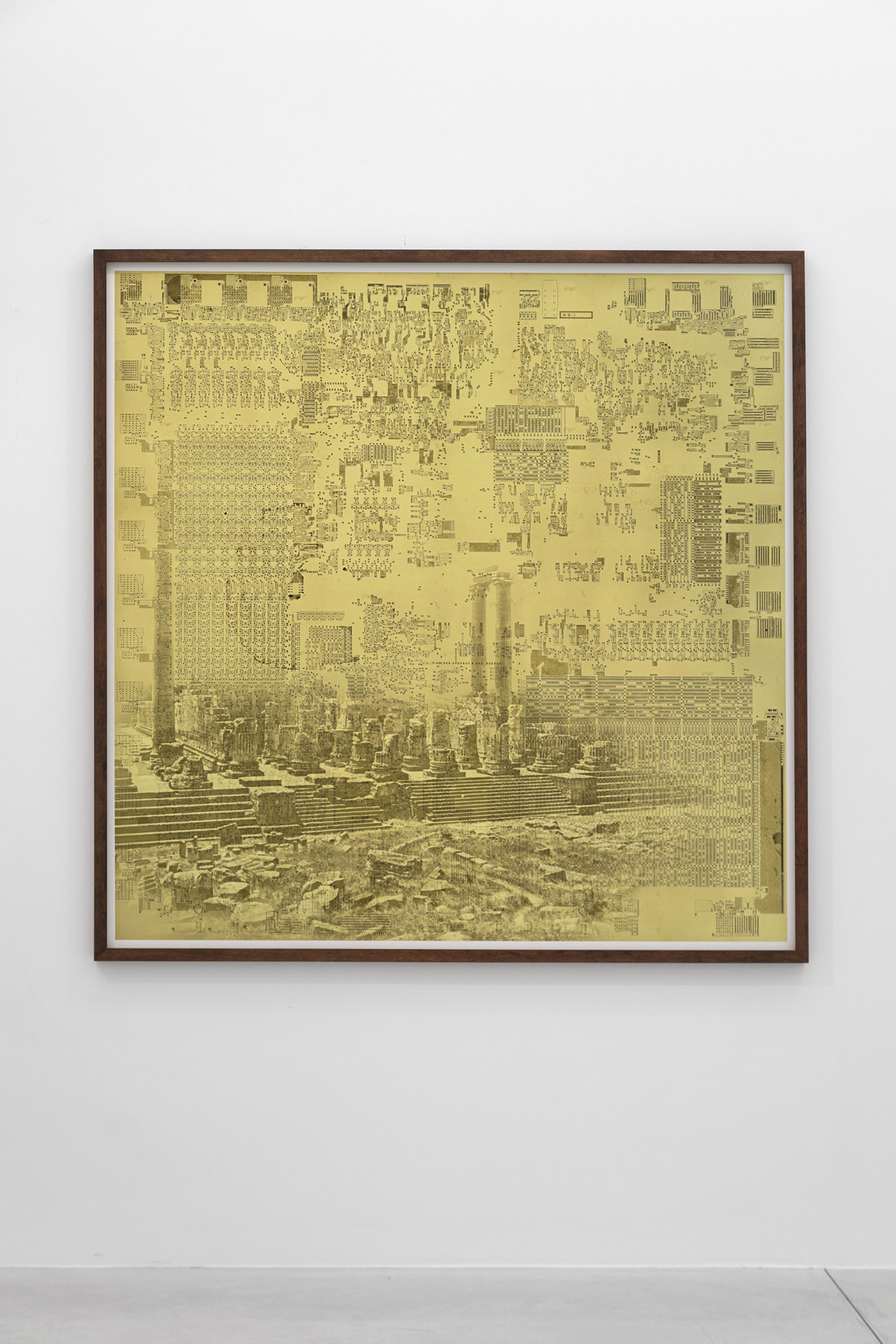

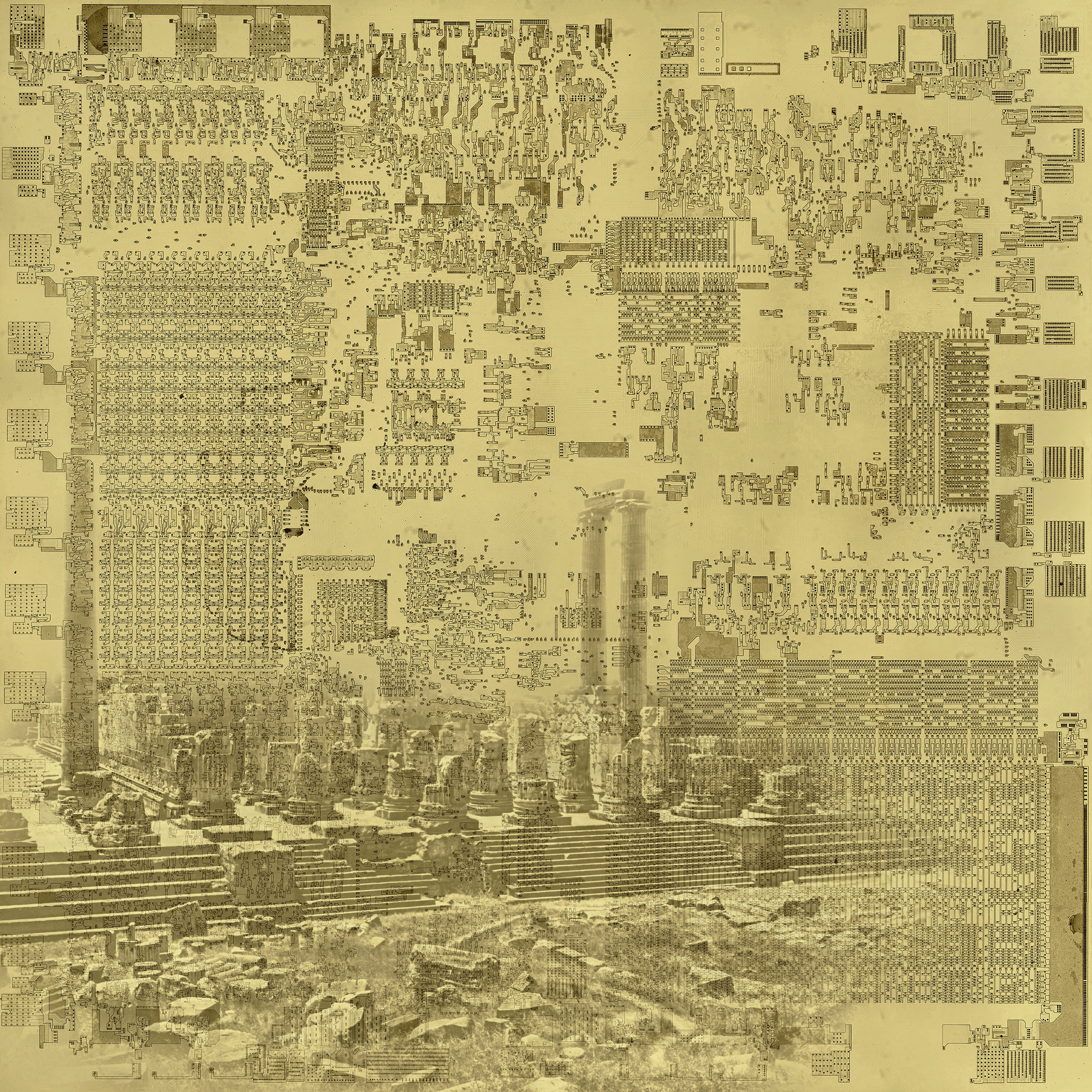

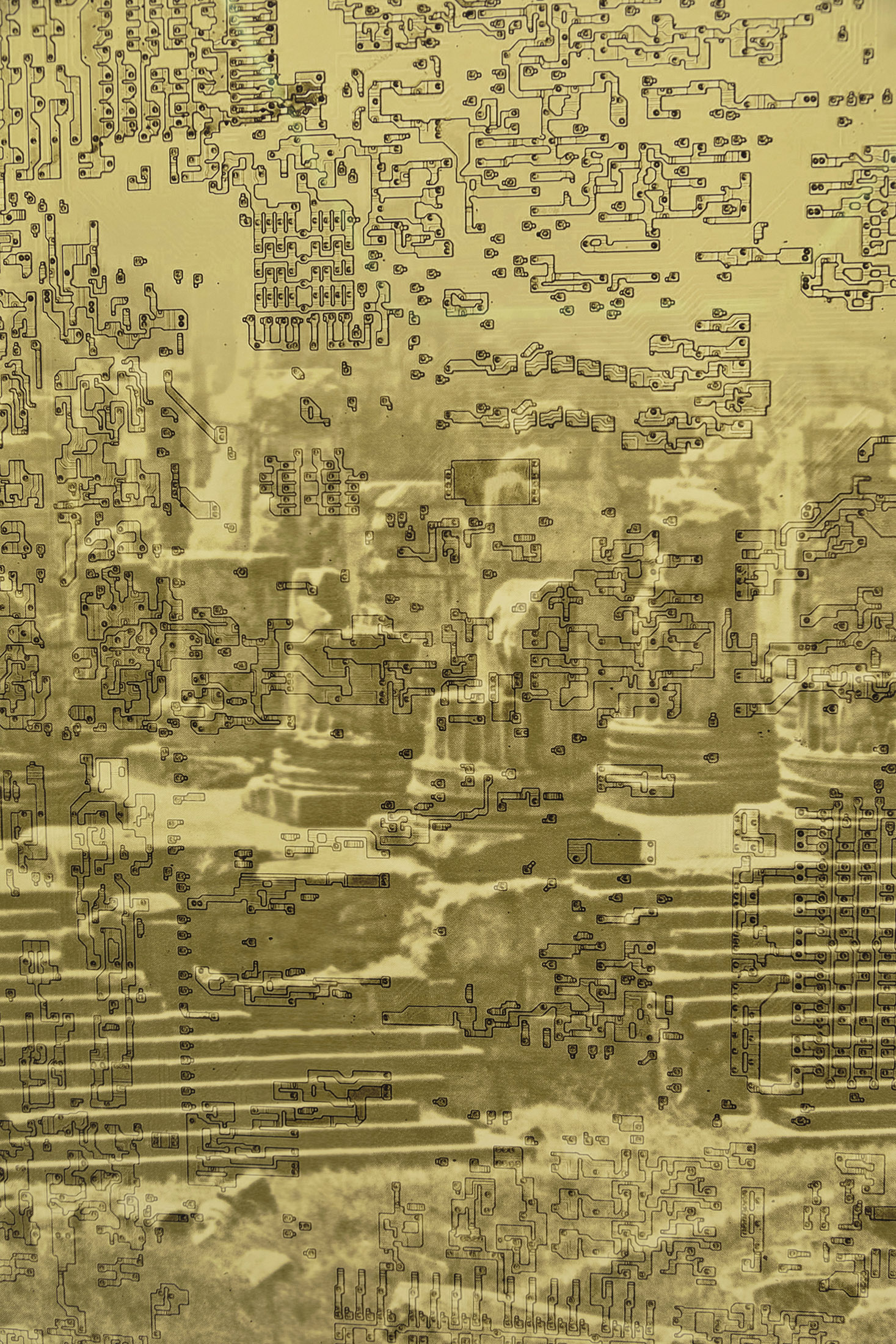

Many thinkers have recently returned humanity to its rightful place, as a living being connected to other species, but also to things. Less anthropocentrism and more understanding and humility are needed in considering our place. This exhibition carries many warnings. The large print of an image of a microprocessor superimposed on ancient ruins reminds us of this once again. The work of Nicolás Lamas focusses on understanding the world through the transformation of the living and the correlations established with technology. He speaks of adaptability and the emergence of the human species, while questioning its potential disappearance. Life and death run through this exhibition. It’s an important and timely reminder.