Artist: Nicolás Lamas

Exhibition title: Times in Collapse

Venue: Centre de Création Contemporaine Olivier Debré, Tours, France

Date: January 22 – August 29, 2021

Photography: Josépha Blanchet / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and ©Centre de Création Contemporaine Olivier Debré

With its insatiable networking of ideas, concepts, objects and images, Nicolás Lamas’ exhibition is a metaphor for living matter and its countless cycles. But the living matter it references is by no means restricted to human beings: it concerns everything through which energy flows as well as inert matter brought to life by the effects of contamination. Hence, the exhibition takes the form of a gigantic body within which multifaceted changes take place due to interactions between the organism’s various components.

The nave has become a field of action for visitors, who, as they make their way through the exhibition’s itinerary, constantly reinvent the narrative and fictional potential of the works on show, so adding the system’s previously missing link. As Nicolás Lamas himself put it, instead of considering each object in isolation, its purpose is rather to be discerned in the connections and relationships generated between them. This is why everything that might appear absent, forgotten, becomes a fundamental part of the work at hand, starting with the visitors’ physical presence, their viewpoints and infinitely varied interpretations.

The exhibition’s title, Times in Collapse, suggests the disruption of a certain world order. The installation is a dizzying journey through time, from Antiquity to the present day, giving equal weight to fragments of natural matter, mutilated artefacts, rebuses and other more or less clearly identified remains. Connected so incongruously with one another, these ersatz realities cannot but provoke reflection, perhaps even incredulity. Lamas asks a multitude of questions that transcend language, referring to rules yet to be established and in most cases finding the beginnings of answers in the intuitive, error, chance and the unsuspected.

By making use of the “commercial display” technique, a scenographic procedure whose application to presentation of artworks has recently come under study1, Lamas focuses the exhibition on critical points of view that our contemporary societies might give rise to: the future of our ways of life in the face of the rapid changes that our planet is undergoing due to overproduction and overconsumption; in contrast, the notion of wandering, meandering, the bargain-hunter’s casual rummaging; and in between the lines, the desire for the beautiful, the search for something lasting, our capacity for resilience in the face of disasters, wars and epidemics.

Highlighting the mundane and imbuing it with value, encouraging us to look more closely at the anecdotal, the abandoned, even the ugly, the artist’s every action relates to this impressive undertaking that seeks to relativise humanity’s importance on the Earth by focusing on other potential lifeforms. In the era of transhumanism, humankind’s central position on the planet is called into question in favour of a broader vision of life, taking account of the possible interactions between all living organisms, in their infinite ability to intersect and hybridise. Humankind does not rule here, but interacts on an equal footing with all the other species.

By bringing the various objects’ scales of values into collision, along with their geographical provenances and the eras in which they were created, whether or not they were seen as artworks, Lamas’ work continuously brings us back to the here and now of our condition of being in the world. Times in Collapse, a large-scale composition designed as a single entity, may be interpreted as a vanitas, a contemporary allegory of the passage of time, of our finiteness and various dependences. But this great ecosystem also raises the question of a possible posthuman condition for humankind, assuming the existence of complex, unrecognised interactions likely to provide new hypotheses of life.

As we follow the train of associations of ideas that he suggests, Nicolás Lamas invites us to delve into our imaginations and decide where the objects around us come from and what their destiny might be. There is an urgent need to examine the present in order to better speculate on possible futures. In consequence, our comfort zones are upset, shifted, just as certain journeys we undertake lead us to review our prejudices and shake up our convictions. In a universe where everyday conventions and interactions are turned on their heads, each individual would have to reinvent their own world, new social structures, suitable modalities of existence, different ways of living together.

First of all, the installation relies on presentation systems alien to the museum environment: the artefacts on show are not set on bases or in display cases, but rather in large refrigerated supermarket cabinets. Further along, columns from IKEA storage units form vertical racks, shelving for valuable items, classified and inventoried like a collection in a museum of natural science or cabinet of curiosities. Provoking culture and context shock, building audacious bridgeways between disparities, the artist highlights the gap between the quest for knowledge and mass hyperconsumerism.

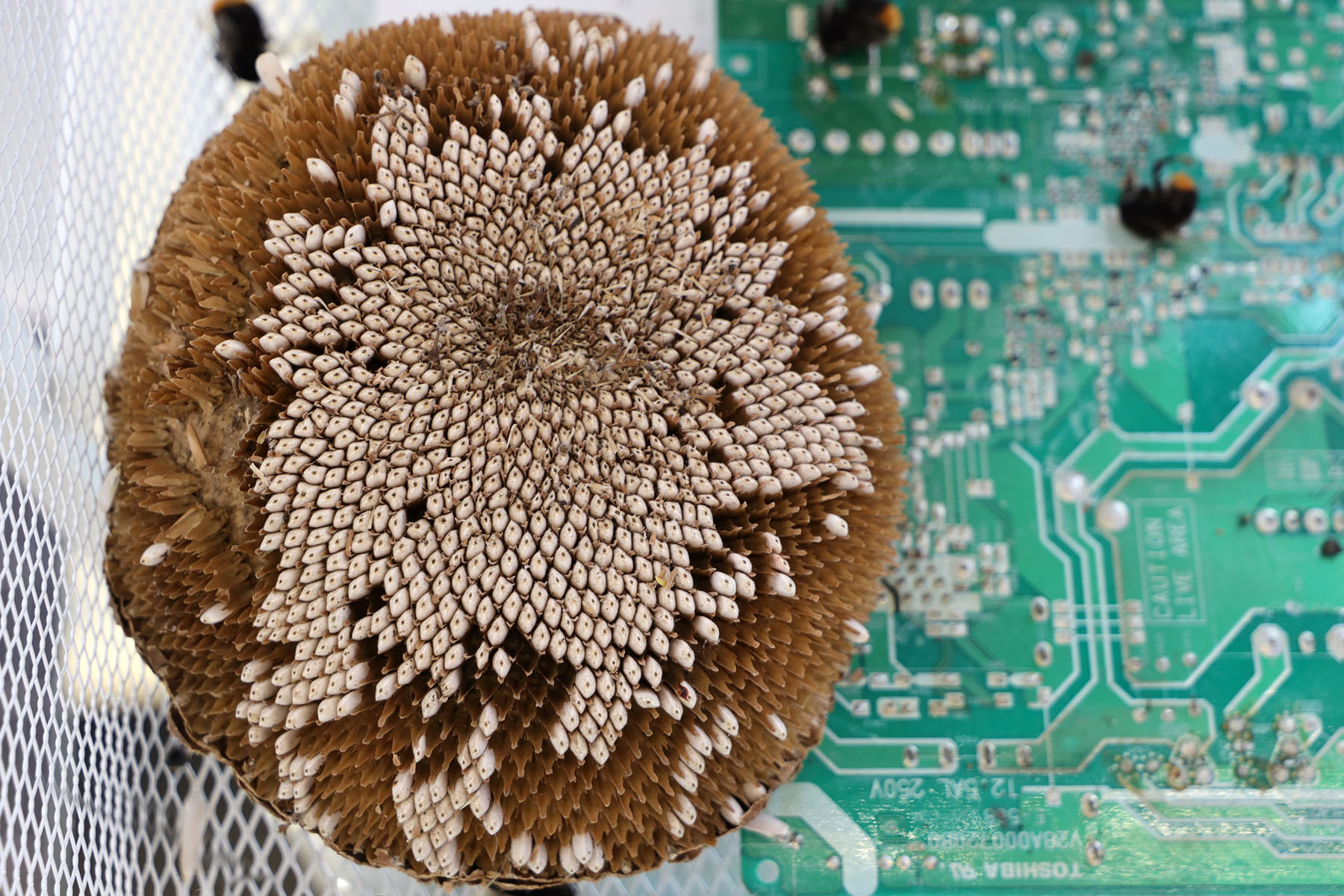

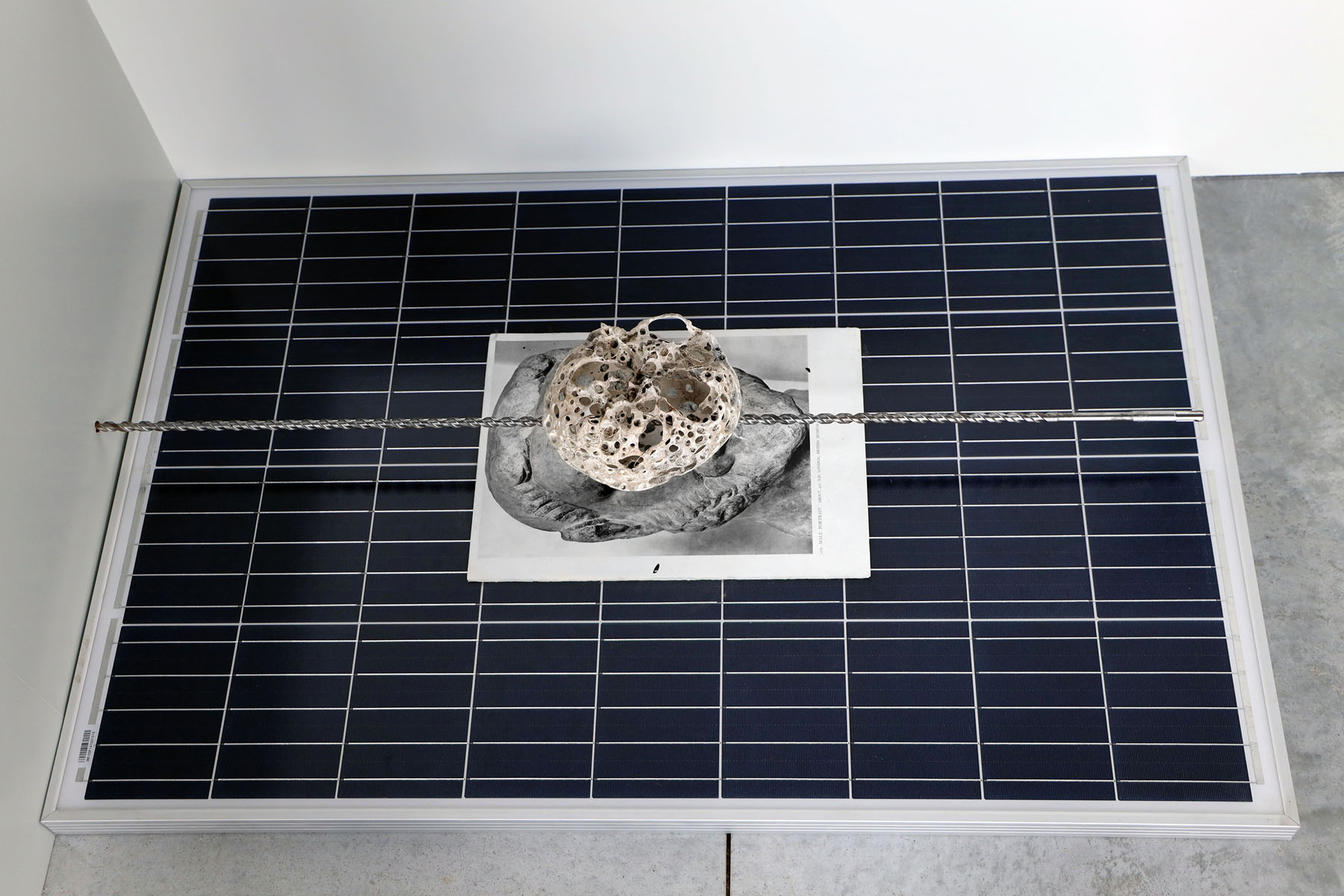

Taken as a whole, the nave becomes a vast landscape formed by a series of islands whose substrata are still in motion. The eye drifts and alternates between verticality and horizontality. A syncretic landscape that does not feature sculptures shaped by the artist’s hand, but rather assemblages and collages without any clearly defined aesthetic, interacting to generate dynamics of forces, pollinations and symbioses, as is the case with the functioning of any community. The associations are certainly surprising: a pair of burnt trainers whose soles have melted but in whose cavities sickly shrubs continue to grow, leathery roots gaining ground on the resistant plastic of the shoes, a sign that life always finds a way in spite of everything. Prosthetic human limbs refer to a present slowed down by constrained gestures, obsolete bodies. In contrast, sedimentary fossils of organisms are evocative of the origins of life. Further off, a wasps’ nest, broken open and dried out, is set on a photocopier like an ancient sculpted head, evoking an artistic vocabulary that has been copied a thousand times over. As if a fresh dispute had broken out between ancient and modern, this incongruous coming together seems to express the notion of a game that pits our contemporary world, extoling innovation and upholding the idea of progress, against a return to Antiquity, symbolising perfection and the culmination of an unsurpassable style.

In the refrigerated cabinets – attempts at long-term conservation, a determination to freeze living matter – a whole world of objects dialogues interdependently. A transverse flute is paired with a bone in reference to the first prehistoric flute. A copy of a classical philosopher’s bust can be seen through a computer keyboard layout screenprinted on a windowpane. Right beside it, an imposing marine plant spreads its countless networks of fragile little tendrils like the brain’s synapses. Giving concrete expression to the notion of knowledge and its various forms of transmission, this confrontation of images speaks to us of language and its translations, from orality to writing, from the Classical Age to modern technologies.

In Lamas’ work, the animal and plant kingdoms, as well as the mineral world, are constantly interacting, overlapping in order to hybridise, so producing new species straight out of fiction, a virtual reality that might well become our everyday experience given the incisiveness and lucidity of this view of our environment. It is up to us to explore it and find whatever will enable us to visit the world in its subjective beauty, as Hans Bellmer suggests in his Petite Anatomie de l’Image: “(…) an object, a woman’s foot for example, is only real if desire does not inevitably take it for a foot”2. Hence, our desires can project specific identities onto things, the memory of an experience or the invention of a personal reality.

By purposely choosing objects from all eras, the artist has provided us with an anthropological history revisited in the light of multiple potential futures. Like an archaeologist drawing on the traces of a past civilisation in order to reconstruct the missing components of a relic, Lamas turns to the past to seek out what may enable us to imagine the future, bridging the interstices with reversible prostheses.

The vertical features in the centre of the nave are references to the column as a classical architectural component and pillar of all systems. Set atop a photocopier whose inner workings are left visible, a replica of a torso of the Phrygian satyr Marsyas, flute player and inventor of music, imposes its presence in all its subtle poetry and fragility. In its gradual evolution, mass reproduction raises the question of progress alongside that of loss, as the details of information tend to dissipate as time goes by.

In another area, stranded in the midst of a stretch of stagnant water, a legless black plaster Venus is enclosed in a dark orange plexiglass column whose protective walls are perforated with a diagram of an electronic network, another indication of the flows of information in constant circulation in the exhibition. Perched on a base composed of old hard drives from obsolete computers, the goddess’ seemingly charred body has lost its canons of beauty and stands frozen in a pool of dirty water.

A crashed car lies at the bottom of the same pool, annihilated by speed and giving free rein to the idea of a time now past when oil was still used to provide energy for travel and exchanges. With no trace of nostalgia but highlighting the rapid, almost uncontrollable changes in our contemporary world, this area with its apocalyptic overtones is intended as a departure point for a new era, unrecognised as yet perhaps, but in which the notion of post-humanism opens up new possibilities. After dusk has fallen, everything that comes from the earth returns to the earth in order to live once again in other ways.

[1] Natacha Pugnet and Arnaud Vasseux (eds.), Faire étalage, Displays et autres dispositifs d’exposition, Nîmes School of Fine Arts, 2019.

[2] Hans Bellmer, Petite anatomie de l’image, Editions Allia, Paris, 2005.