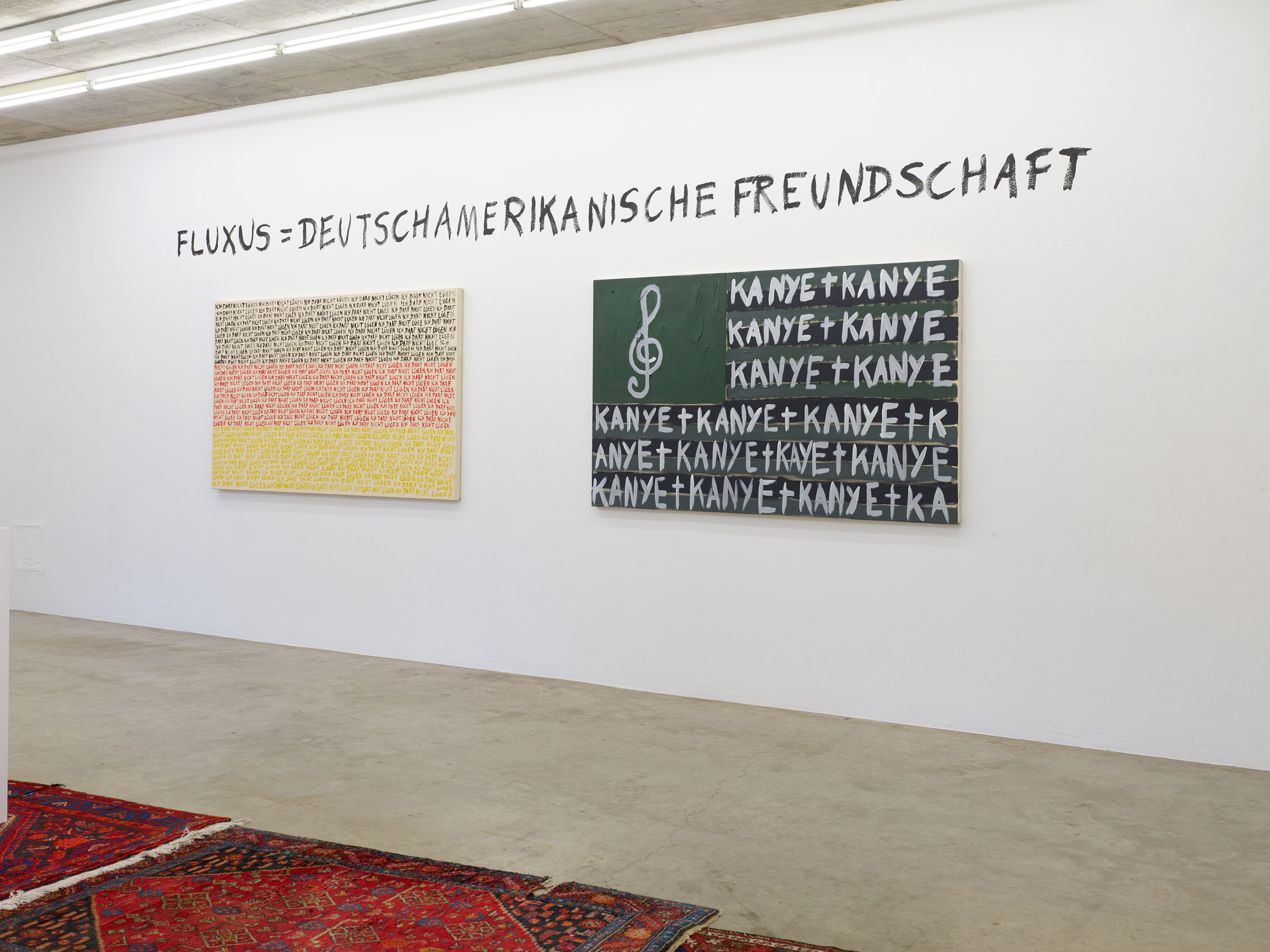

Artist: Nicholas Warburg

Exhibition title: FLUXUS

Venue: NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen, Germany

Date: June 9 – July 28, 2024

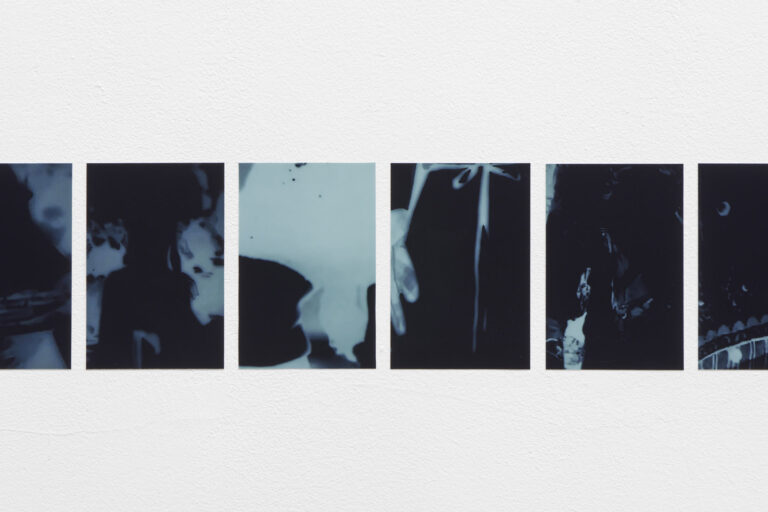

Photography: Simon Vogel / all images are copyrighted. Courtesy of the artist and NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein

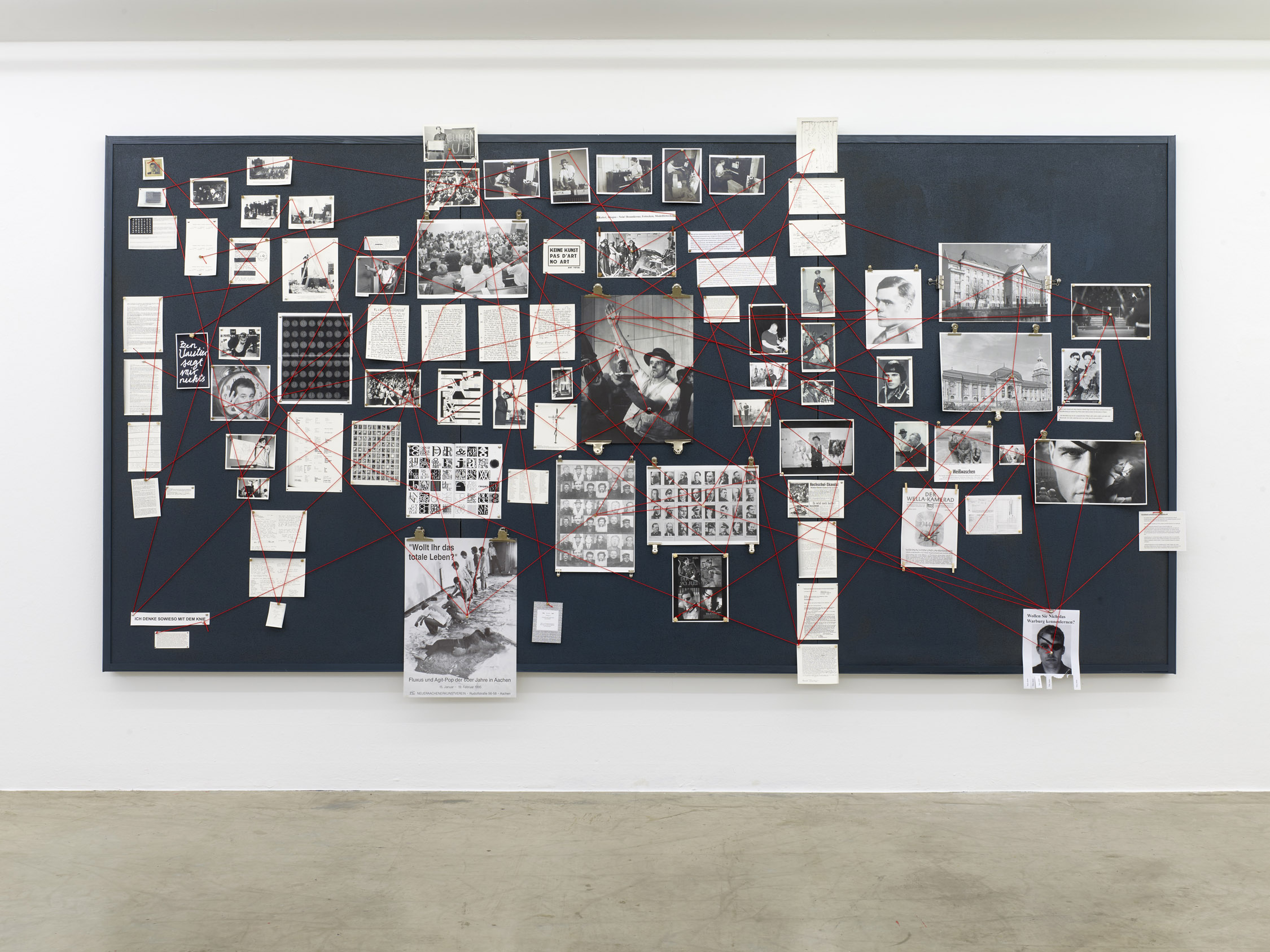

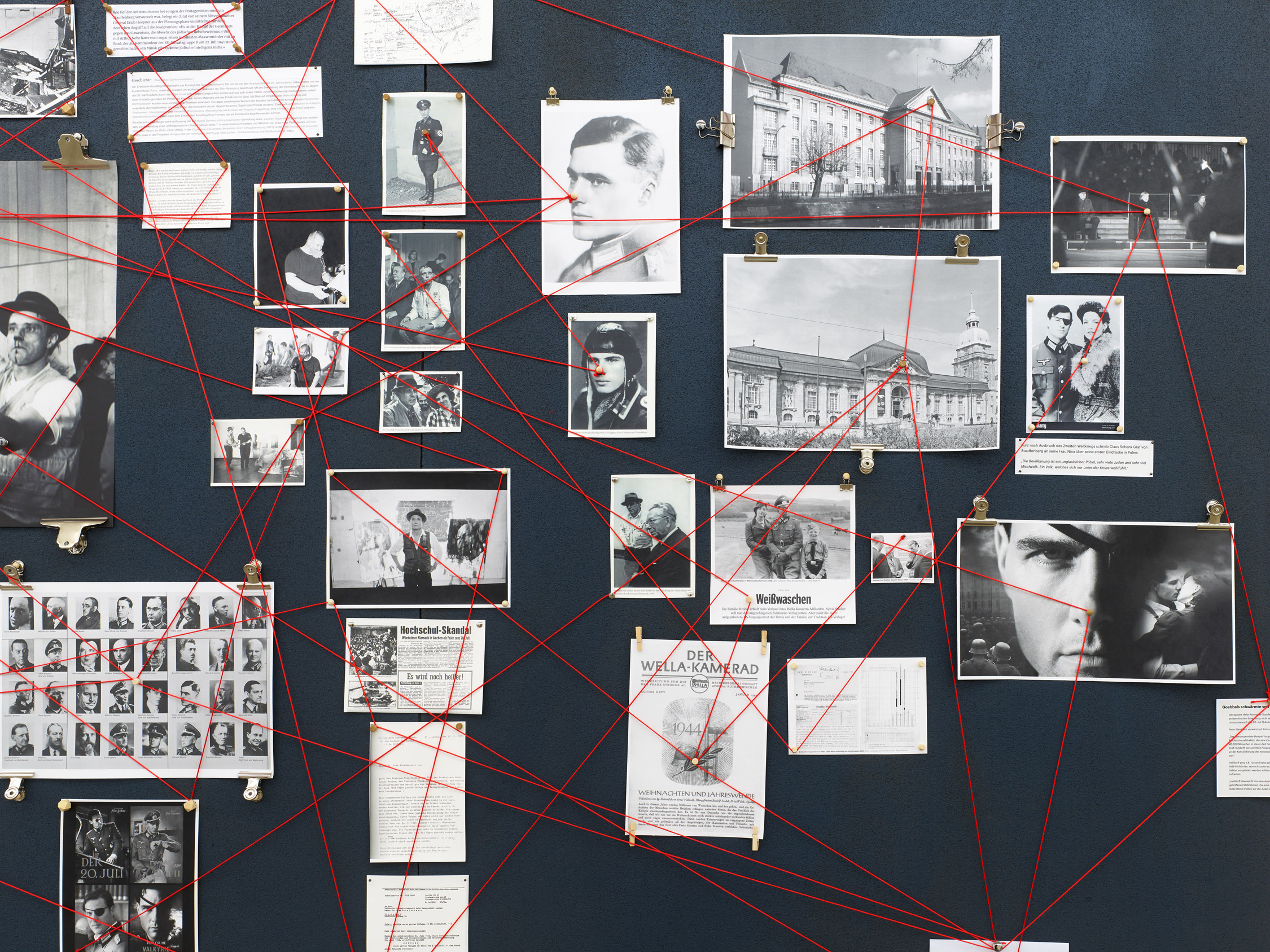

From June 9 to July 28, 2024, NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein is showing the exhibition FLUXUS by Nicholas Warburg. The duration includes the sixtieth anniversary of the Aachen Fluxus Festival on July 20, 1964, which in turn took place on the twentieth anniversary of the Stauffenberg assassination. Warburg is practicing the preservation of traces of a movement that spent and wasted itself in rebellion against rigid border guarding in the arts: Fluxus=luxury? The central work of the solo show will be an expansive “Crazy Wall”; a pinboard with photos, maps, newspaper clippings and diagrams, diligently repainted by the artist in a forensic manner – connected with red string, in the way that investigators or ritual murderers do in films. In Warburg’s Crazy Wall, the boundary between the creation of meaning and paranoia is fluid: BENDLERBLOCK BEUYS MEMORIAL STATION OF EXPANDED CONCEPT OF RESISTANCE.

Let’s start at the beginning: the “Festival of New Art” with around one thousand spectators in the Audimax of Aachen Technical University ended in a scandal and had to be broken off prematurely. An angry student had punched Joseph Beuys in the face. Beuys fought back and staggered across the stage with a bloody nose, a crucifix in his left hand and his right hand raised in the Hitler salute in a bizarre exorcism. The “Festival of New Art” was opened by Bazon Brock with a speech that he himself underlaid with an endless loop of the tape recording of Joseph Goebbels’ Sportpalast exclamation “Do you want total war?”. Fluxus was a moment of shock in the old Federal Republic of Germany: the Second World War was over, the economic miracle secured many Germans a livelihood and a new self-confidence. However, almost twenty years after the end of National Socialism and its ban on “degenerate art”, a climate of social and cultural stagnation still largely prevailed in Germany. In this stifling atmosphere, Fluxus opened a window.

_______________________________________________________________

Exactly twenty years earlier, on July 20, 1944, a group led by Colonel Count von Stauffenberg had unsuccessfully attempted to kill Hitler. Was this really resistance in the emphatic sense of the word, or rather an attempt to thwart a German surrender at a time when defeat in the Second World War was foreseeable? The conspirators of July 20th came from the military and administration of Nazi Germany, many of them from the former nobility, and were avowed anti-Semites and anti-democrats. They used the Bendlerblock in Berlin, headquarters of the General Army Office, now the “Bendlerblock – German Resistance Memorial”, as the center of their preparations for the assassination attempt.

_______________________________________________________________

It is no longer known exactly why the artist and Fluxus founder George Maciunas chose the Latin word Fluxus – for flow, throughflow or dissolution – for his movement. Perhaps “flow” was too trivial for him or too close to the world of finance. One could think of “cash flow” or “affluent” (rich, wealthy). In German, we know the phrase “to be fluid”. Again, “to be fluent in a language” means to speak a language fluently. The Fluxus artists made the discovery of a wealth of artistic languages. With Fluxus, something entered the art world that can be understood as the temporalization of the visual arts. Through Fluxus, space without time, as it has always been understood by conventional, genre-proof art production, and time without space, as it is understood by music, were able to merge.

_______________________________________________________________

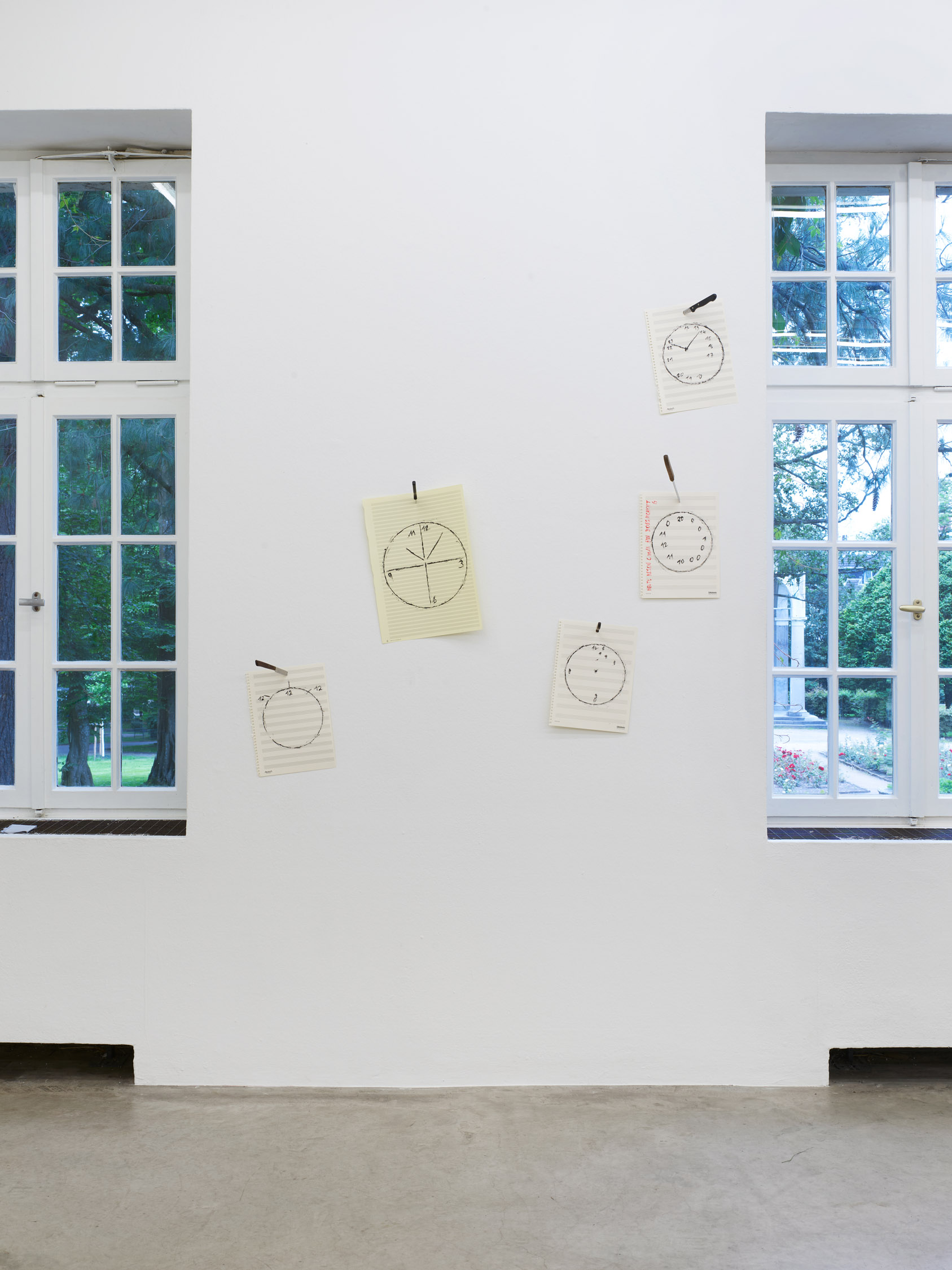

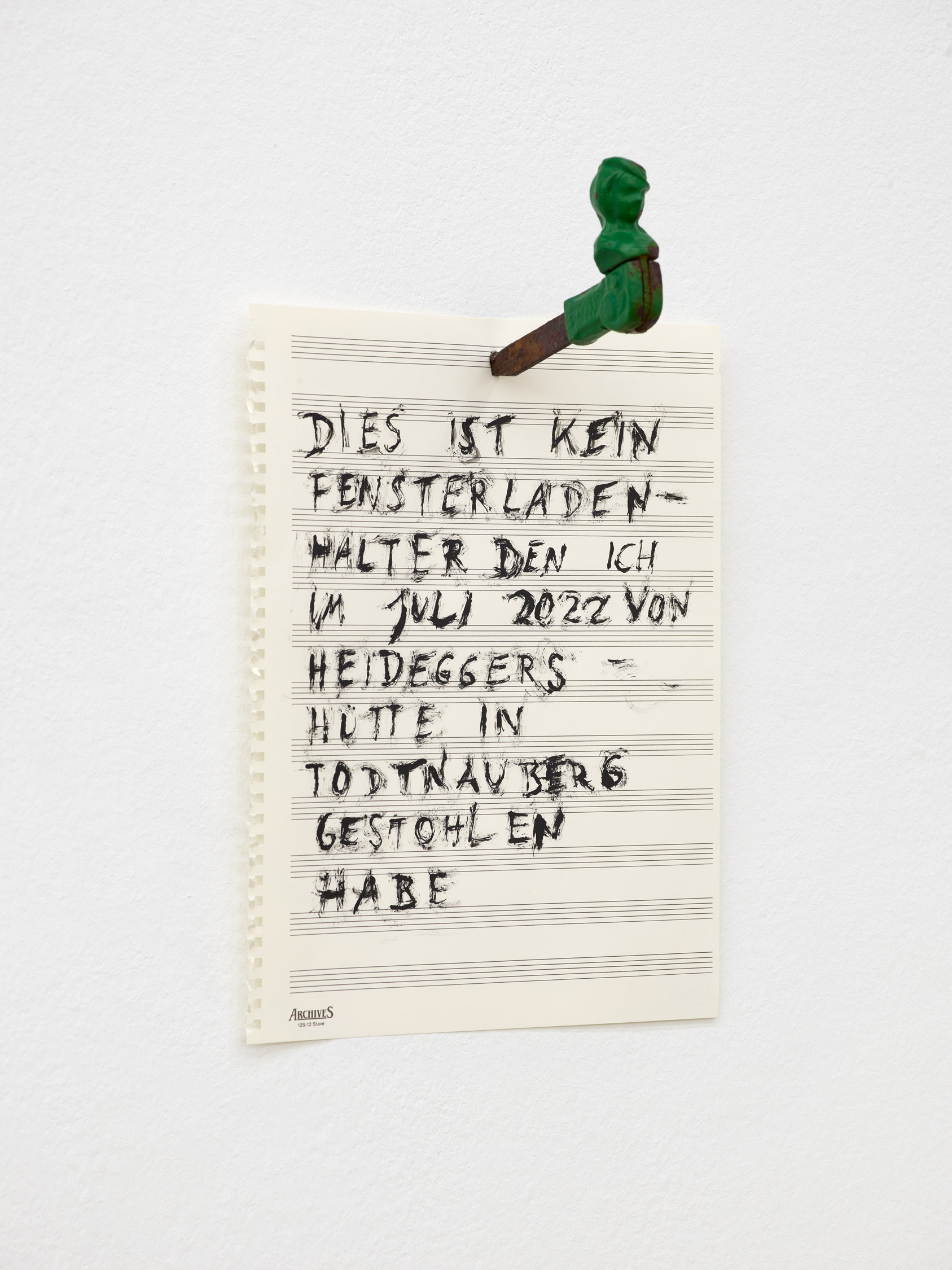

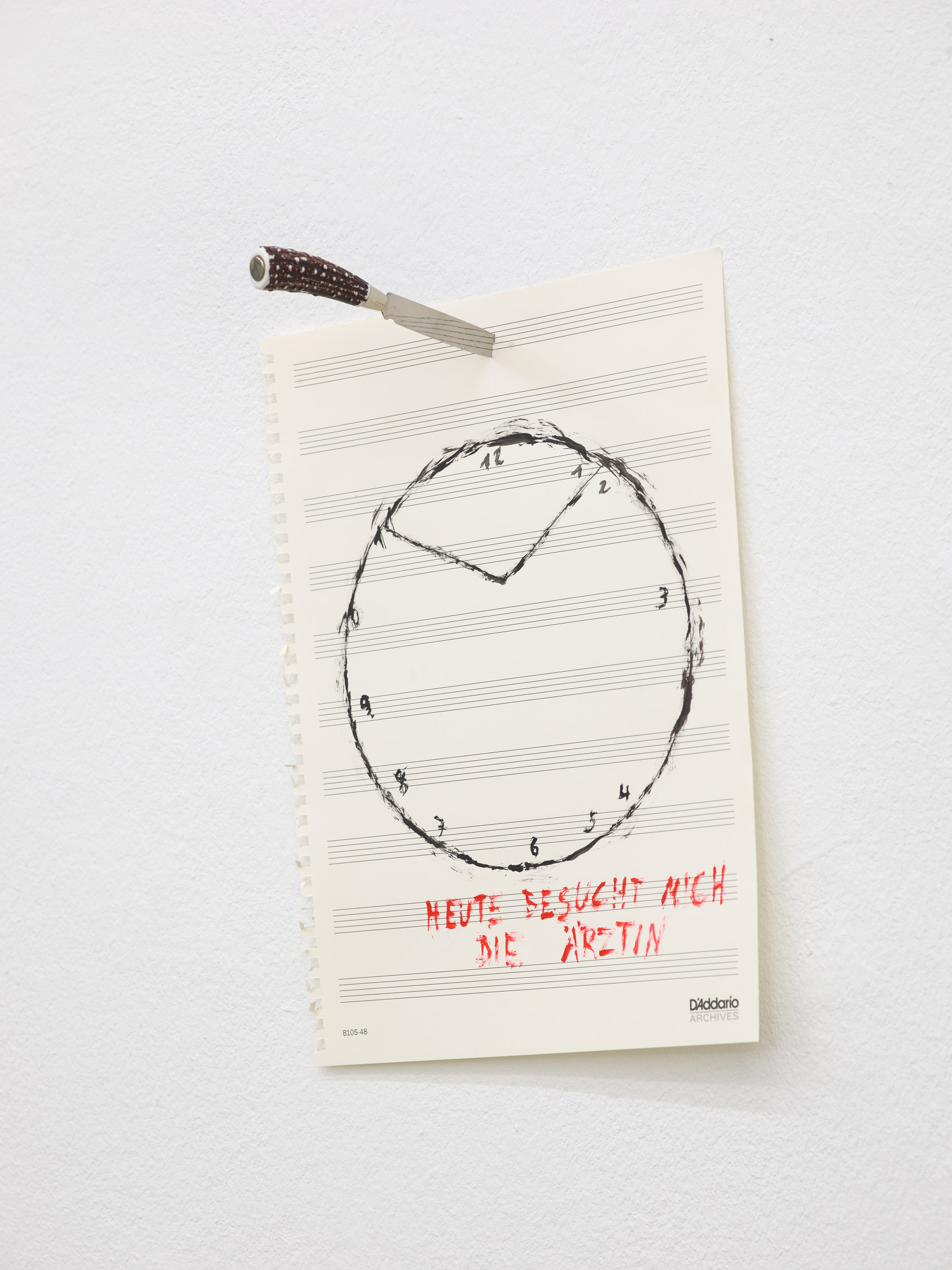

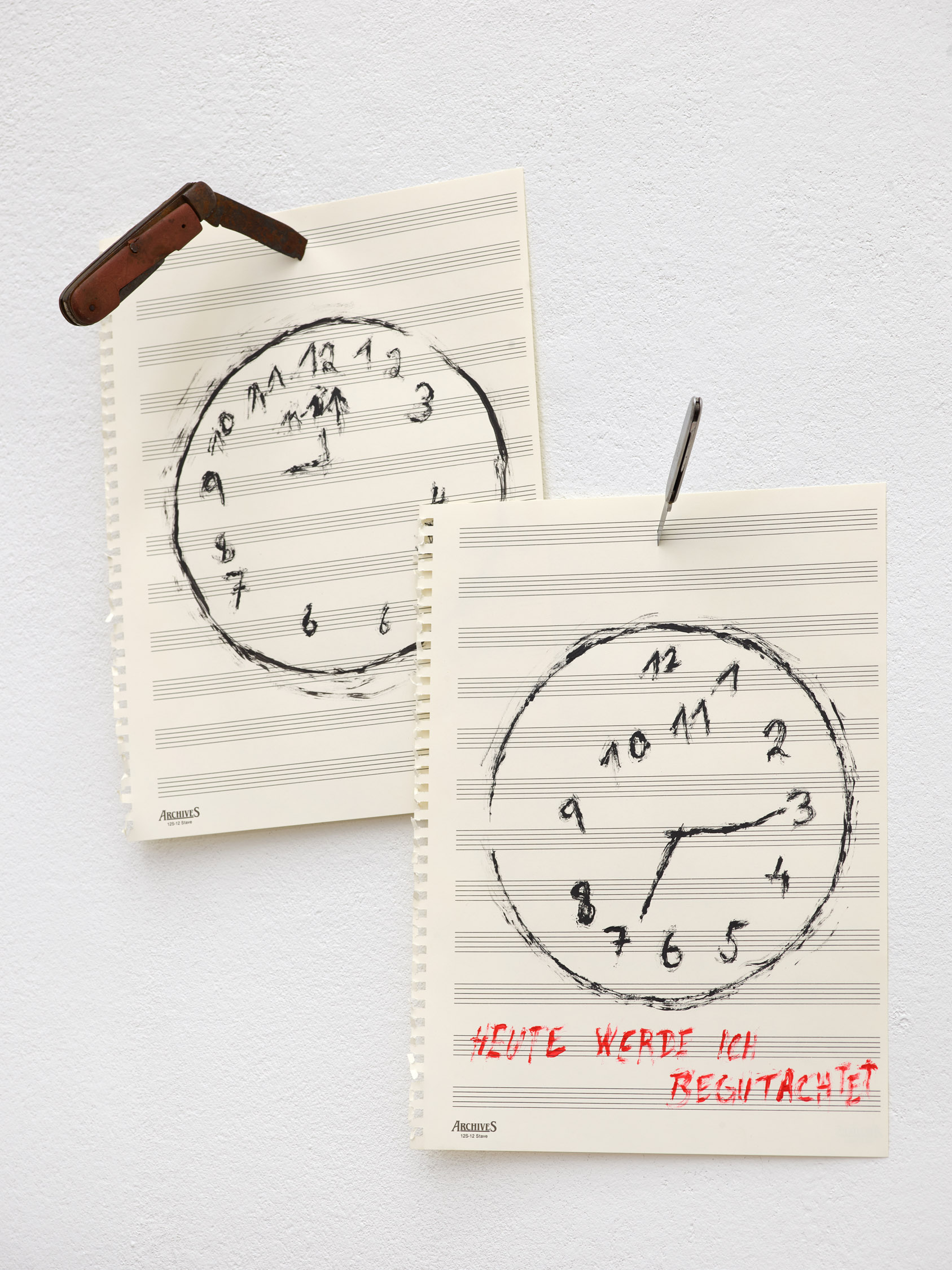

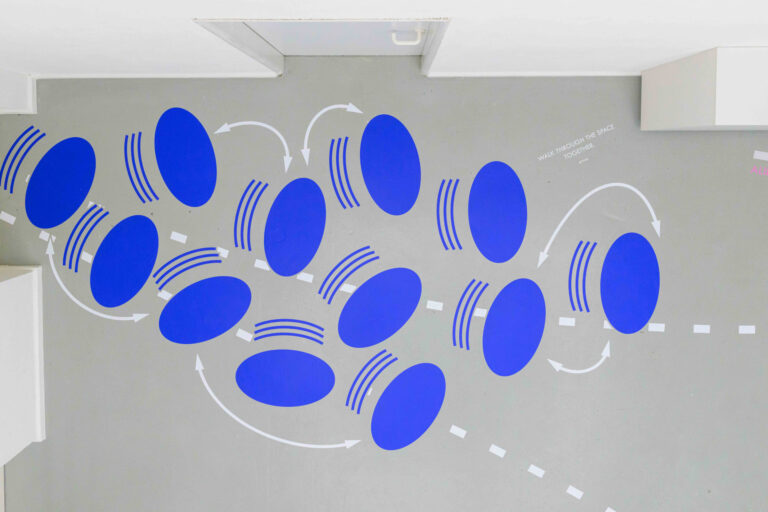

A path of red Persian carpets guides visitors through Nicholas Warburg’s exhibition. Once past the FLUXUS store in the entrance area, you will find hundreds of manic drawings of clock tests on music paper. Clock tests are used to diagnose dementia in order to examine memory performance. The music sheets are rammed into the walls with knives. Once you have passed a conspiratorial circle of two-metre-high crucifix-like scarecrows, the carpets lead you to the upper floor, where the central work of Warburg’s solo show opens up under flickering neon lights: an expansive “Crazy Wall” – an oversized black pinboard with photos, maps, newspaper clippings and diagrams painted by the artist with forensic diligence; connected with red string, in the manner used in films by investigators or ritual murderers. Beuys called his action sequences “Kukei, Akopee – Nein!, Braunkreuz – Fettecken – Modellfettecken”. The Beuys case features prominently in Warburg’s forensics: an often difficult to disentangle mixture of ingenious border shifts in art, criticism of authoritarian structures, but also questionable rope teams, magical, even folkish figures of thought, not least in the derivation of his expanded concept of art, which sometimes has an overtone of the creative power of the people.

_______________________________________________________________

Shortly after the Fluxus Festival, Beuys met the art collector Karl Ströher. Ströher was the heir to the Wella company in Darmstadt. He had been one of the founders of a local branch of the “Stahlhelm” in his hometown and financially supported the NSDAP shortly after the transfer of power to Hitler. Karl Ströher and his brother Georg used forced laborers and participated in armaments production; the company’s sales exploded from 1939 onwards. They denounced their former business partners Hol-lander & Kohn as Jews and took over their businesses. The Ströhers claimed this Aryanization as a tax reduction at the tax office and sued Hollander & Kohn even after the war because they had copied the name of a Wella product, which they themselves had coined before the Aryanization. In 1967, Ströher bought a complete exhibition of Beuys’ work and secured the right of first refusal. The resulting collection is the source of the “Beuys Block” in the Landesmuseum Darmstadt, the world’s largest coherent complex of Beuys’ works. Without Ströher, Beuys’ career from the 1960s onwards would not have been conceivable in this form. He soon topped the international art rankings of Capital magazine. Art = capital, Fluxus = luxury? Are Nicholas Warburg’s red threads obvious or paranoid? What is the artist trying to tell us: BENDLERBLOCK BEUYS GEDENKSTÄTTE ERWEITERTER WIDERSTANDSBE-GRIFF?

Nicholas Warburg (*1992, Frankfurt am Main) studied art at the California Institute of the Arts in Santa Clarita and at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. He is co-founder of the collective Frankfurter Hauptschule, which has attracted attention with spectacular interventions in public space since 2013. His work, which often adresses German history and art history with an air of ambivalence, has been awarded with prizes and scholarships of Künstlerhilfe Frankfurt, Polytechnische Gesellschaft, Stiftung Kunstfonds and neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst Berlin.