This side of Paradise (dot dot dot)

Paradise is a slippery concept. One bound with connotations of enclosure yet excessive, leaking at the edges with symbols, tropes and narratives. Fueled, Oasis, Fueled expands on Mónica Mays’ interest in paradise as an ambivalent notion pervaded by semantics of finitude, and by extension of loss. For her first solo exhibition at Pedro Cera, the artist presents a series of sculptures and waxed canvases that posit the concept of paradise as a framework for the intertwining of a genealogy of historical domination with logics of desire, extraction and commodification.

*

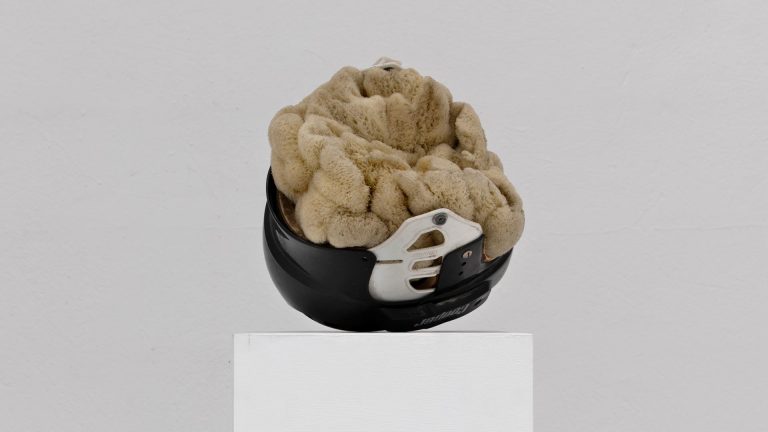

A collection of intricate assemblages populates the two floors of the gallery’s Madrid location, climbing up the walls or restlessly oscillating in imbalance over their pedestals. Deprived of their function, those hybrids of industrial remnants are covered with funerary fabric, plaster, wax, tree resins, myrrh, damar and offcuts of dried animal skins, materials charged with both a preservative and a ritualistic quality. A dubious carnality emanates from their scale and surface, as organic and affective fluxes alike seem guided through the automobile exhaust systems serving as skeletons for their embalmed limbs.

The first theory of modern economic flows, one prompted by the advent of global trade and colonial expansion, was informed by scientific discoveries on the human blood system, appropriating the vocabulary of drains, supply and pressure from the body. In her work, Mays draws a parallel between the genesic format of Paradise, actualized through scriptural and popular imagery, and the logics of domination and extraction inherent to contemporary trade systems. The palm tree is a common symbol of paradise, ornamenting oases and scriptures alike. When reduced to the liquid commodity of palm oil, the tree becomes an odorless, tasteless, ubiquitous omnipresence that pervades every layer of modern life, saturating arteries and maritime chokepoints, taking the shape, scent, and savor of everything it infiltrates and thickening its essence with vacuous fat. Writing on God, Heraclitus confessed: “He takes various shapes, like fire. When it is mingled with spices, [it] is named according to the savour of each”.

Fire and fuel are recurrent materials in Mays’ process, though they only manifest in the finished work as traces, burns and drips. Combustion and lubrication are logics that pertain to flows of commodities, Christian rhetoric and eroticism. There is a curious blend of care and sadism in the way the artist assembles her sculptures in her Madrid studio, shrouding their amputated limbs with cataplasms while melting and molding them to her will.

Mays dismantles school furniture, repurposing them as pedestals for the sculptures. Laid open, a remnant of their function, they ghostly uphold the pieces. These assemblages are left covered with traces of use, carrying into their new (after)life fragments of intimate narratives and confessional gestures from their previous usage. The prodding limbs of the works are concluded with pieces of the same domestic quality: elements of beds, sewing machines, desks. The tiny buttons suggest lactation as much as erection, imbuing the pieces with a wry kinkiness. Lingering as they do in the white cube, they seem to be waiting in absence (that of a god or a lover), hoping to be turned on by a caress or a wet dream. Elevated by cardboard plinths echoing the modern flow of commodities, more recent works appear alternatively enraged and aroused at the promise of their upcoming shipment, ambivalently expecting a modern Rapture aboard some anonymous container ship.

Principles of rigidity and flexibility guide the compositions. In Feeding, falling, flying (III), 2024, the exhaust systems Mays uses are mounted with flexible segments of weaved metallic fibers, preventing the rigid structure from cracking from the tension of circulation. Alternatively, Suspensions are shock absorbers on the terrain where we are rolling, 2024, are perfected by suspensions, springing devices meant to mitigate the weight gravity puts on a vehicle. Suspension of disbelief was a recurring concept in my conversations with Mays, whether applied to art or fantasy, as a pact suspending the implausibility of the narrative and allowing for poetic faith. Fiction, like Paradise, requires a covenant. As a recurrent tale of morality and power, the fall from heaven is an instance of beauty and perfection being cast by a higher power, either from a holy mountain or delightful garden, into hell or a world of chaos where wings are cut and nudity is shamed.

A suspended saddle ornate with weaved palm leaves and discarded conveyor belts partially blocks the gallery’s staircase, suggesting a lexicon of sexual, industrial and animal domination while bringing in mind more pious images: Jesus entering into Jerusalem on horseback, welcomed by a crowd waving palm branches, an event now celebrated as Palm Sunday. In punctuation, suspension points are used to convey either an interruption of thought or an excess of meaning. When used in epistolary exchange, it most often suggests innuendos. Mays uses suspension in both ways, plus a third one I would position between fetishistic and mystical, something suggesting both religious levitation and BDSM’s subspace.

*

English poet / cherub soldier Rupert Brooke wrote his renowned poem Tiare Tahiti on the shores of the pacific island where he spent three months in 1914. A now outdated and exoticizing ode to the promise of afterlife, the text contrasts earthly pleasures he encountered there with their true form in the kingdom of heaven:

There the Eternals are, and there

The Good, the Lovely, and the True,

and Types, whose earthly copies

were the foolish broken things we knew

Then later:

Snare in flowers, and kiss, and call,

With lips that fade, and human laughter

And faces individual,

Well this side of Paradise! …

The suspension points leave the last line open, as if unsure which side to choose. This hesitation is central to Mays’ practice. Brought together as the characters of a fragmented comedy of manners, her sculptures take on the role of lurid angels fallen from a junkyard of delights where pleasure and grace irrevocably intertwine. Alternatively fragile and robust, devout and irreverent, sub and dom, they beg the question: which side? Which shore?

In an essay on puppetry I sent Mays ahead of our conversations, Kleist wrote: “Paradise is bolted. We must journey around the world and determine if perhaps at the end somewhere there is an opening to be discovered again”. Through a display of unresolved appetites, her work for Fueled, Oasis, Fueled offers an aesthetic experience of conflicted desires: earthly pleasures or celestial bliss. Far from reiterating the moral dichotomy of Christian discipline versus hedonistic diversion, her interest in the logics of domination, domestication and pleasure, along with their wistful channeling through historical and personal narratives, forms and images, allow for a third way. One that remains undefined but all the more enticing, arguing for indeterminacy as a protocol for affection (if not paradise). One that unabashedly abolishes the distance between critical thinking and erotic impulse, between the discursive and the visceral, and maybe between both sides of Paradise.

-Simon Leibenson