Artist: Mihai Platica

Exhibition title: The Wide Open Skin

Venue: BARIL, Cluj, Romania

Date: May 10 – June 15, 2016

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and BARIL

The body is at the core of contemporary culture: youthfulness, attractiveness, healthiness, flexibility are only a few amongst our principal preoccupations concerning it. Between gorgeous, bronzed, powerful, damaged warrior bodies and fragile, white, clean, infected, injured surfaces of the skin there is a vast territory of social and cultural constructs and body techniques. From our childhood we learn the ways of disciplining, cleaning, maintaining and regulating our bodies, the rules of being in good health. Becoming adult is often a process of reinventing our body practices. The body is about politics, social order and cultural regulation. When it comes to body we are confronted by a great deal of beliefs, scientific affirmations and social expectations. Between scientifically approved statements and popular convictions there are huge gaps yet borders are easily transgressed. For a cultural anthropologist or a social historian all this is a fact: they have that famous alienated eye which has the ability to observe from outside the familiarity of those daily practices and the ability to question their self-evidence. It’s like looking from space at our species, realising how nonsensical can be all that struggle from that remote perspective. Yet, that alien’s eye is not about criticism, it’s about comprehension. Marcel Mauss invented the concept of the techniques of the body observing American women’s different way of walking from that of the European ones. Due to Georges Vigarello and a team of French historians we know how radical differences were between the 19th Century and our time in terms of hygiene. Amongst many other examples it is mentioned that while in the 19th Century it was prohibited to take a hot bath more often that once a month, today we have shampoos and shower gels specially designed to frequent use – even twice a day. In those smilingly superficial facts lies practically a fundamentally different system of medical and theological convictions: in the 19th Century the temperature and the weight of water had an important role in curing diseases and those qualities of water were connected to pleasures or abstinences. Mihai Platica’s works propose an investigation into those techniques and our ability to observe and show them.

So perplexingly simple and complex, the body is the core interest of these works, whose method is its meticulous observation and documentation. They want the viewer to stop by the surface of things, by the body as the surface of humans. The unknown is hidden in the surface. Mihai Platica’s works are an anthropological investigation about the body as a cultural given.

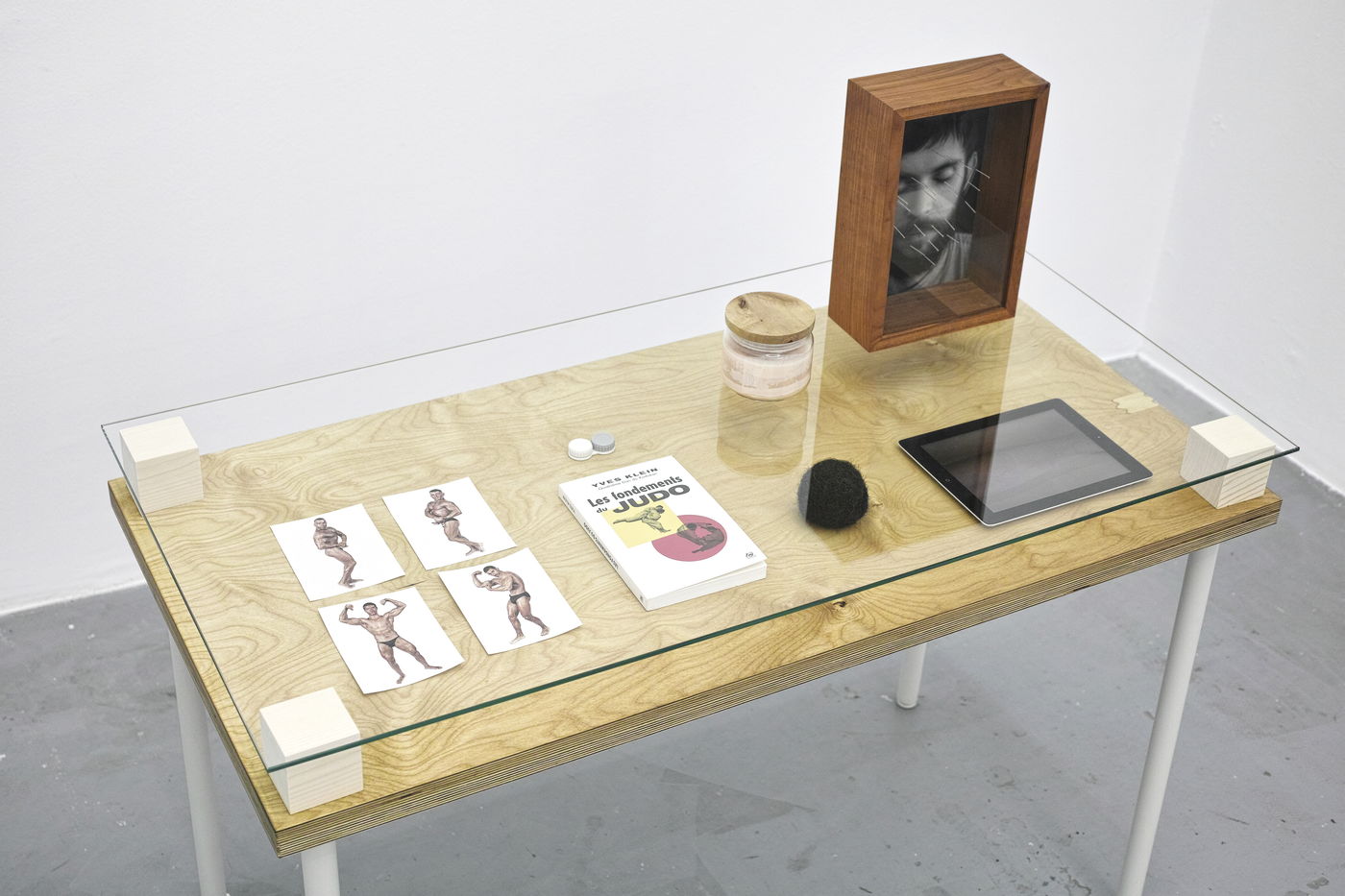

We are seeing bodies taken out of their contexts. Those bodies are naked in a particular way: not the clothing, but their context is missing. The camera’s lens stops by the rectangular muscles of a bodybuilder on a white surface. The mark of a surgery on another photography becomes the way of being of the body and not just the sign of a traumatic memory similarly to the injured body in another picture which has to exist till recovery.

Traces that bodies are leaving behind them or spaces that they are shaping and occupying are another territory to explore. The signature that someone retraced – one hand following another hand’s movement, the swimming pool where there are no bodies only many possibilities of bodies are subtle examples of a way too natural physical presence.

A third way of exploring the techniques of the bodies are the objects related to bodily reactions or interpreted through physical effects. Cure shows a cream conceived to heal the body: the domestic medicine shows how we care for the body, how we try to ease it, to be in good relations with it. Botanophobia is the opposite: it shows how objects (in this case, plants) produce unease, physical pain, anxiety, psychological fear caused by a specific environment of the body.

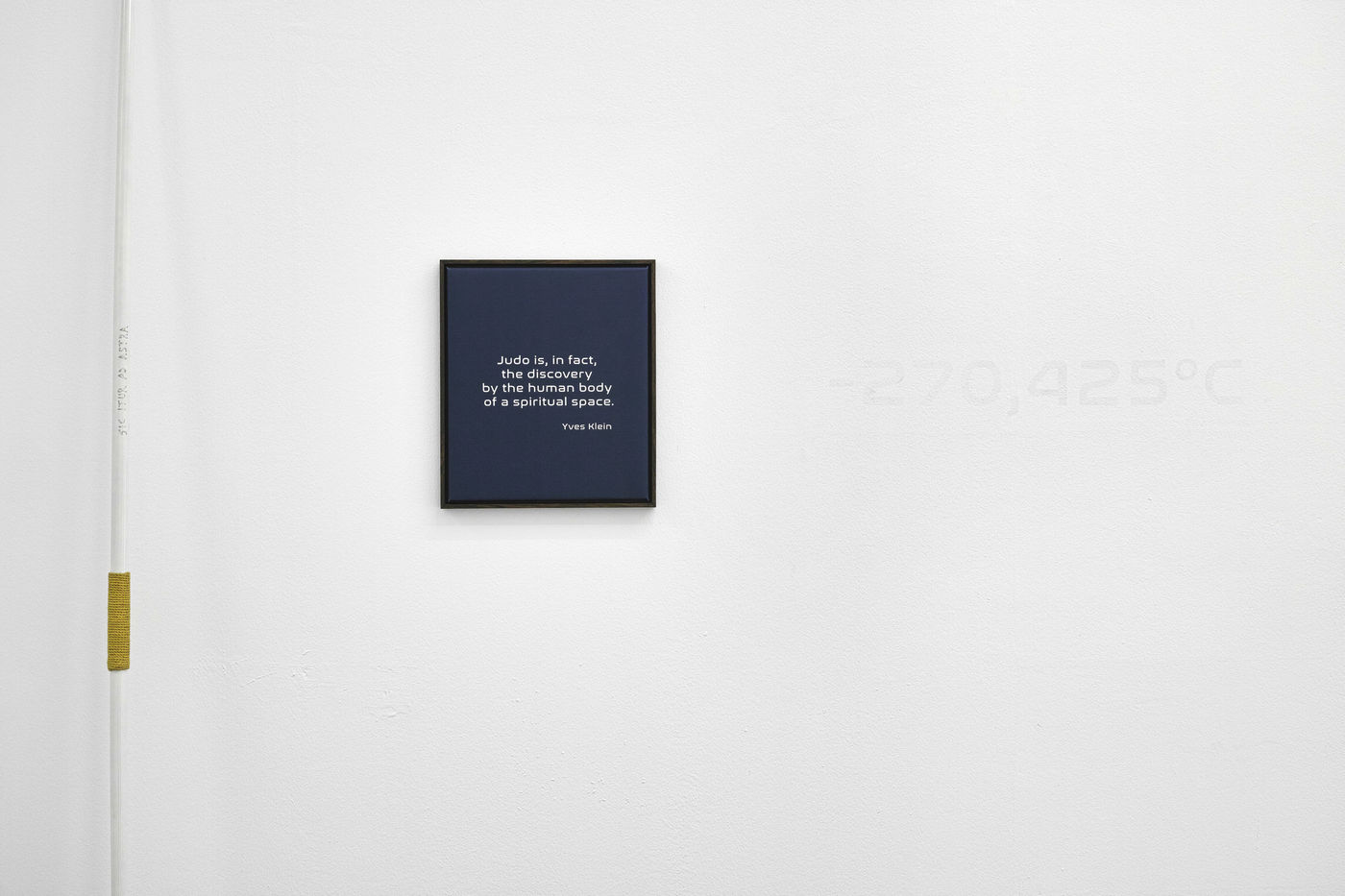

Finally there are two more philosophical objects amongst the works of the exhibition. Their philosophical ambitions are somehow eased by humour. One of them is the arrow engraved with the text: Sic itur ad astra. The object of the arrow becomes perfect metonymy. The other is a French historical work about our cultural concepts of cleanness wrapped in sterilised plastic. Metonymy again, synergy of concept and object.

The exhibition leaves us at the crossroads of objects, bodies and rules in the cultural, social and spiritual space of our physical existence.

Anna Keszeg (1981), born in Turda, Romania, is a cultural theorist and researcher in communication and fashion studies. Her art related papers appeared in ArtGuideEast Journal, Apertúra, Korunk, Múzeum Café.