Artist: Michael Ross

Exhibition title: Selected Works 1991 – 2015

Venue: Ellis King, Dublin, Ireland

Date: January 29 – March 5, 2016

Photography: images copyright and courtesy the artist and Ellis King, Dublin

The story is often told of Alberto Giacometti’s exile from occupied Paris in the early 1940’s, as he whiled away the time in his native Switzerland working on a series of figurative sculptures of literally diminishing returns. When he finally boarded the train back to France at war’s end he found that all the works he had produced over these years could fit into a few matchboxes. A decade earlier Marcel Duchamp had created a deluxe edition of sixty-nine tiny replicas of his best-known works, designed to fit into a dedicated container. This is the minituarised monograph – a portable ‘greatest hits’ – we now know as his boîte-en-valise (‘box in a suitcase’). Both of these precedents came to mind as I arranged to meet Michael Ross in a downtown Manhattan café just before Christmas in order to discuss the exhibition he was planning for the Ellis King Gallery in Dublin, three thousand miles and an ocean away, early in the New Year. There was, he insisted, no need for a studio visit. He could, in effect, bring his studio with him and was happy to do so.

Such historical antecedents are especially appreciable at a time when much contemporary art seems to hail from Brobdingnag rather than Lilliput, as Jonathan Swift might have put it. That said, they may ultimately be of limited value in accounting for Ross’s work, given that the signature scale of his miniscule sculptures has less to do with formal refinement (Giacometti) or conceptual encapsulation (Duchamp) than with a more fundamental appreciation of smallness as a quality in and of itself. Ross has been aptly described by the curator Ralph Rugoff as ‘a true scholar of the tiny kingdom’.[i] He cites as the inaugural work of his mature career a thimble filled with dust, which bears the self-consciously grandiloquent title The Smallest Type of Architecture For the Body Containing The Dust From My Bedroom, My Studio, My Living-Room, My Kitchen And My Bathroom, 1991. Much that remains characteristic of his art to this day is heralded by this early sculpture; in particular the deft combination of a small number of disparate elements into a succinct assemblage, garnished with an expansively suggestive title. That said, the thimble is atypically iconic, its ballast of associations (domestic labour, bodily protection, fairy-tale tininess) unusually up-front. These days Ross’s sculptures are more likely to be composed of constituent parts whose identity – which is to say, their originally designated purpose – is not so immediately apparent. These commonly unregarded, but newly repurposed morsels of industrial metal, coloured plastic, off-cut fabric or discarded paper are only vaguely familiar at first sight, even when they have not been customised out of all recognisability.

The sheer heterogeneity of his scavenged materials suggests the instincts of a born hoarder whose magpie gaze might snag on almost anything, under favourable circumstances. Yet, as this body of work has developed over time, some predelictions have become evident. These include a fondness for hinges, clasps, clips and fasteners, whose cumulative prominence hints at a thematics of connection and consolidation, however arbitrary or provisional. Of course, there are practical as well as formal reasons for favouring these elements, given how the works are physically held together. Likewise, commonplace screws are necessarily incorporated into the composition of these minute wall-hung sculptures. That said, these fixtures are positioned with a disarming sophistication, one that bears comparison with Robert Ryman’s approach to the similarly compositional fittings which support many of that artists’s most accomplished paintings.

In fact, some of Ross’s most compelling constructions are as pictorial as they are sculptural, especially those composed of abutting or overlapping flat planes. These can sometimes call to mind archetypal forms that have occupied image-makers down through the ages: a female torso, say, or an exotic bird or mythical beast. His titles tend to facilitate such readings, which the viewer might otherwise be tempted to dismiss as fanciful. Generally speaking, these titles are as varied in nature as the sculptures they desiginate, and may lead us in any number of interpretive directions, be it towards art history (Untitled (Judd), 1994), politics (Bamiyan, 2005), biography (My Favourite Green Shirt in a Hinge, 1991) or aesthetics (Flexible Materials for Gas and Light in a Suspender Clip (to Marvel and Reflect Softly), 1994).

Previous commentators have noted how exhibitions of Ross’s work flirt with invisibility. Usually hung in a generously interspaced line along the gallery’s walls at eye-level, such presentations share something with that strain of contemporary art that compels the viewer to reflect on habitual modes of addressing an art object within the ambience of its institutional setting. This is not, however, their primary motivation. Momentarily teasing us with the possibility that there may be almost nothing to see, these sculptures quickly thereafter command the kind of intimate, up-close attention more often elicited by jewelry than sculpture per se. In spite of the conventional gallery prohibition on ‘touching the art’, these works are as palpable as they are visible, almost begging to be explored manually as well as visually.

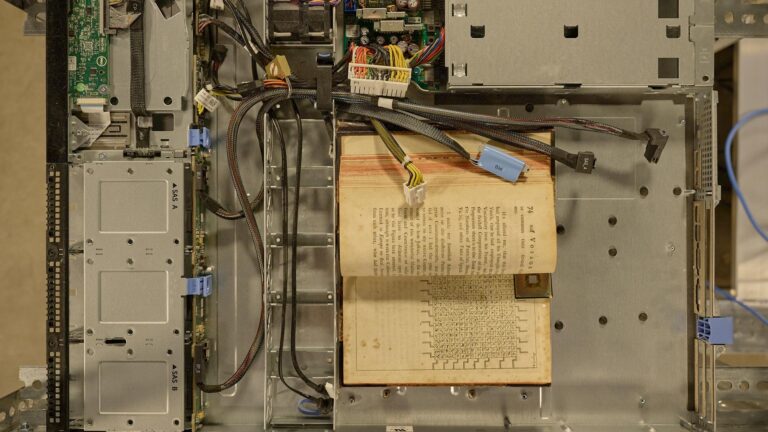

While Ross is a visual artist rather than a writer, his interest in language extends well beyond the evident care he takes with his sculptures’ titles. It is, for instance, also manifest in an occasional series of works executed in engraved microtext on metal. These texts are invented rather than quoted, though they are often informed by the works of specific authors. For his first solo exhibition in Ireland, Ross has returned to a writer who has long interested him, the inveterate wanderer Patrick Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904), who was born in the Ionian islands, raised in Dublin and later became an expert in the literature and legends of Japan, where he lived for many years. The notion of a pronounced aesthetic affinity between Japan and Ireland has been a commonplace in Celtic Studies since it was first proposed by Hearn’s great contemporary, Kuno Meyer. While this fact is unlikely to have impacted on Ross’s text in this instance, it is difficult to deny that his work as a whole has that same ‘precision and suggestiveness’, in Seamus Heaney’s phrase, for which the Japanese haiku and the Early Irish lyric are equally famed. According to Heaney, it was the ‘devotion to succinctness, to formal concision’ of the medieval Irish monks that confirmed them as consummate artists ‘whose response to a detail of the world was a response to its whole mystery.’ Somehow, this seems an appropriate note on which to end a brief introduction to the work of Michael Ross.

Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith

January 2016

[i] At the Threshold of the Visible: Miniscule and Small-scale Art 1964-1996, Independent Curators Incorporated, New York, 1997, p.9.

Michael Ross, Bamiyan, 2005

Michael Ross, Bamiyan, 2005

Michael Ross, Flexible Materials for Gas and Light in a Suspender Clip (to Marvel and Reflect Softly), 1994

Michael Ross, Flexible Materials for Gas and Light in a Suspender Clip (to Marvel and Reflect Softly), 1994

MichaelRoss, Untitled (Judd), 1994

MichaelRoss, Untitled (Judd), 1994

Michael Ross, Grey Mirror, 2015

Michael Ross, Grey Mirror, 2015

Michael Ross, Shishi, 2015

Michael Ross, Shishi, 2015

Michael Ross, Figment Mechanique, 2015

Michael Ross, Figment Mechanique, 2015

Michael Ross, Boulle, 2015

Michael Ross, Boulle, 2015

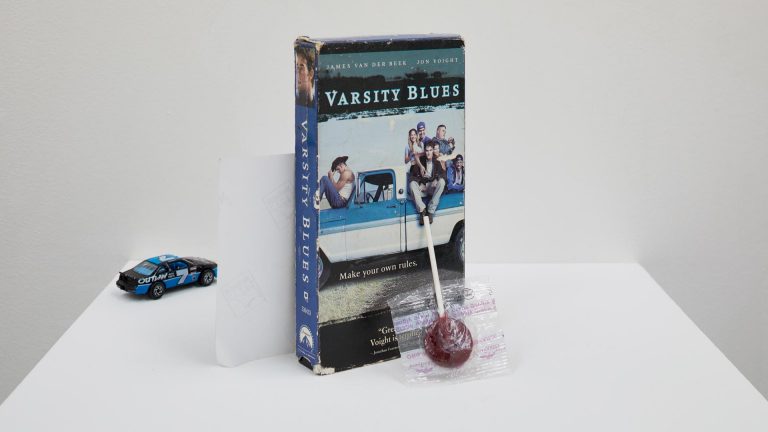

Michael Ross, Bully, 2015

Michael Ross, Bully, 2015

Michael Ross, Twin Hoard, 2005

Michael Ross, Twin Hoard, 2005

Michael Ross, Doppelganger II, 2014

Michael Ross, Doppelganger II, 2014

Michael Ross, Sinister A, 2005

Michael Ross, Sinister A, 2005

Michael Ross, My Favorite Green Shirt in a Hinge, 1991

Michael Ross, My Favorite Green Shirt in a Hinge, 1991

Michael Ross, microtext (Hearn), 2015

Michael Ross, microtext (Hearn), 2015