Artist: Maximiliane Baumgartner

Exhibition title: I don’t sing beautiful songs for pictures

Curated by: Moritz Scheper

Venue: Neuer Essener Kunstverein, Essen, Germany

Date: February 16 – April 21, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Neuer Essener Kunstverein

The title of Maximiliane Baumgartner’s exhibition at the Neuer Essener Kunstverein, „Ich singe nicht für Bilder schöne Lieder“, [“I don’t sing beautiful songs for pictures”], already deals with the mediation of painting. In it, the representative façade of the Kunstverein migrates into a series of paintings created with reference to Jean Genet’s play The Balcony. Genet’s play reads as a parable of an all-encompassing longing for representing and the preservation of power, but also of the deceptive aspect of images and their supposed meanings.

In the paintings, the balcony motif is used as a multi-layered metaphorical parable for contemporary political conditions. Depending on the context, it may symbolize a transitional space, the threshold between the private and the public, but also the exposed position of representing. At the same time, the balcony, and with it every picture of him, forms a scenographic element for Baumgartner that spans a space for the mediation of her own work.

Due to this, Baumgartner’s work splices two fields, which usually remain separated, although they actually depend on each other: On the one hand the artistic proposition, and on the other, its aesthetic and content-related mediation. Educational reformers can be found in it, as can reformist play settings or references to architecture and public space. Moreover, Baumgartner breaks up the isolation of individual images through the special formats of her images, which seek points of contact with the spaces of their presentation through their exceptional cuttings. Accordingly, individual paintings become scenic elements that open up a space leading to the images, a space that could perhaps be described as a space of mediation. Concretely, this step from surface into space is acted out with the façade front of the Kunstverein here, which Baumgartner deliberately plays into the space.

The spectrum of distancing and involvement also takes place at the level of content. Three of the paintings refer to the post-democratic emptying of political representation. The German parliament, recognizable by its blue seats, is shown with various painterly means at the greatest possible distance from its visitor’s balcony. In addition, Genet’s drama, which is more of a notion for this exhibition, also deals with the power of images, which is also extremely present in the exhibition. Just think of the image of empty seats in parliament, which the German right-wing party AfD (in repetition of the Nazi-party NSDAP) wants to produce. Or of the parliament in general as an image of representative democracy.

This technocratic apparatus, which comes to nothing in the face of new-right structures, endangers parliamentary democracy from the inside, is compared in the exhibition with the German fable of the donkey who learns to read. This early satire of an ossified technocracy tells of an examination board that can be convinced of the reading skills of a donkey just because it can say Iih-Aah – representatives who satisfy themselves in their function.

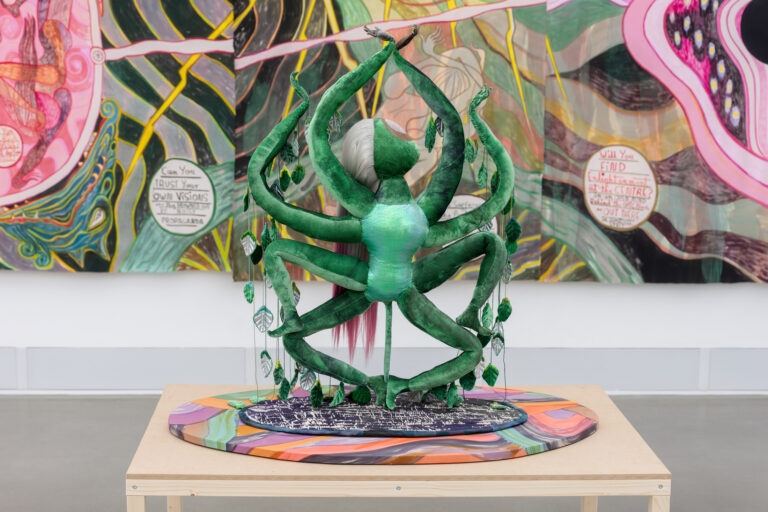

Baumgartner contrasts such a representative with the hidden self-portrait “Wanderpoetinnen I” [“Wandering Poetess I”], which shows the artist in the role of the poet, dancer and life reformer Gusto Gräser, who is performing his bumblebee dance. The picture goes back to a dance that Baumgartner (dressed as Gräser) performed with children and adolecscents in the action space and art educational project “Der Fahrende Raum”. On the one hand, she activates this now somewhat forgotten “figure of the alternative movement” and co-founder of the artist colony Monte Verità, emphasizing a visible break with a rather male-dominated tradition. And on the other, in connection with the exhibited distance to parliament, the picture appeals to get involved.