Artist: Matti Sumari

Exhibition title: [𝘔𝘮𝘮𝘮𝘮-𝘢𝘯-𝘢𝘯-𝘢𝘯𝘶𝘢𝘭 𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘰𝘶-𝘳𝘳𝘳𝘳𝘳𝘳𝘳𝘳]

Curated by: Nils Svensk

Venue: Gislaveds Konsthall, Gislaved, Sweden

Date: April 27 – July 28, 2024

Photography: All works courtesy of the artist / Photos: ©Fredrik Åkum

The Human Body, The Societal Organism and The Industrial Animal

In an act of rebellious and resourceful recycling, Matti Sumari’s artistic practice feeds off the waste of our 21st-century capitalist society. Scouring the back streets of the industrial estate that houses his studio, the artist scavenges for those things deemed detritus, stripped of their previous purpose and found no longer of any use to the unrelenting, ever-expanding organism of the urban environment. Walk around the outskirts of any major metropolitan city, and you will encounter the material excrement of our everyday existence. Once shiny and new, these objects have been fed into the waiting mouth of the consumer machine. Chewed, digested and enjoyed for as long as they are practical or profitable, before being spat or shat out into the alleyways, laybys and streetsides of insignificance.

Air ventilation elements and apertures form the basis of Sumari’s new suite of sculptures. Originally the organs and orifices of an industrial animal’s respiratory system, inhaling hazardous or harmful fumes from a factory floor and excreting them into the exterior atmosphere, or exhaling crisp clean air into poorly oxygenated offices and re-circulating our carbon dioxide discharge into the outside airspace. One sits atop the metallic, barrelled torso of a commercial vacuum cleaner, that insatiable ingester of workplace waste, a subservient sucker that subsists solely off a diet of dust bunnies and debris. Just like its air ventilation associates, the humble hoover can ultimately only resituate and rehouse refuse, unable to ever eliminate it entirely. Out of the societal organism’s sight, out of mind. Our exhalations invisible and our rubbish bagged up awaiting the weekly collection.

The sounds of Sumari’s sonic intervention emerge from the gaping gob of one air duct embouchure. Rumbling, rattling, clinking and clanging indicate the industrial animal’s attempts to verbalise. Employing its mimetic, mechanical voicebox, it parrots the noises it must have witnessed during its time spent aerating an unlicensed party venue in a previous life. A mismatched marriage of repurposed microwave ovens and remodelled table fans forms the jukebox of junk. One the former mainstay of mundane, ready-in-minutes meals for one, the lowest rung on the gastronomic ladder; the other a once temporary, table-top alternative to cooling air conditioning, offering momentary alleviation of oppressive, interior heat. Here, far removed from their original domestic duties in a far-fetched twist of fate, they make sweet music together, harmonising to the tune of tools, motors and hardware.

Rounded, bulbous protuberances and recessed, concave depressions adorn the sculptural surfaces. Painstakingly embossed or debossed by hammering into the sheet metal by hand – a conventional craft technique likened to Japanese tan-kin metal forming or traditional repoussage/chasing – they become sunken, reflective pools or swollen, mirrored bulges. When often appearing in pairs, they resemble buttock impressions of the sort that might occur when an excessively sedentary lifestyle meets a favoured spot on a sofa (as Homer Simpson erratically exclaimed “You better not be in my ass groove! It took me years to forge that grove”). Sumari entertains that innate temptation to squeeze oneself into the pre-stamped seating and invites visitors to lower their posteriors into the predetermined indentations. Alongside, as if developing a symbiotic or parasitic relationship with the industrial animal, sluglike pickles attach themselves to the metallic exteriors, much as the remora fish latches onto the belly of a basking shark. The artist admires slugs, snails and other gastropods for their ability to rarely appear out of place, allowed as they are to roam the world mostly unencumbered, ruled by their own intuitive, internal logic.

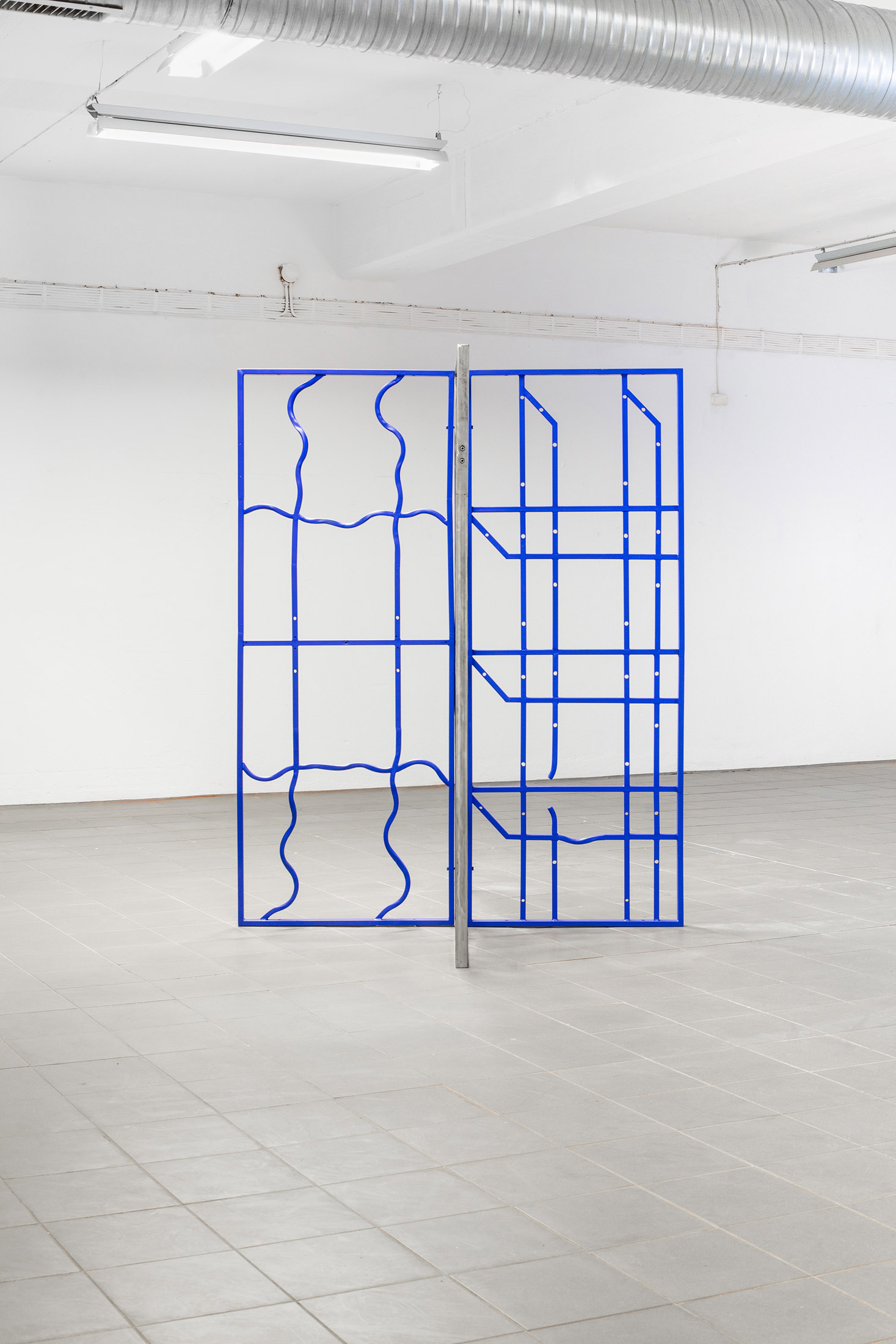

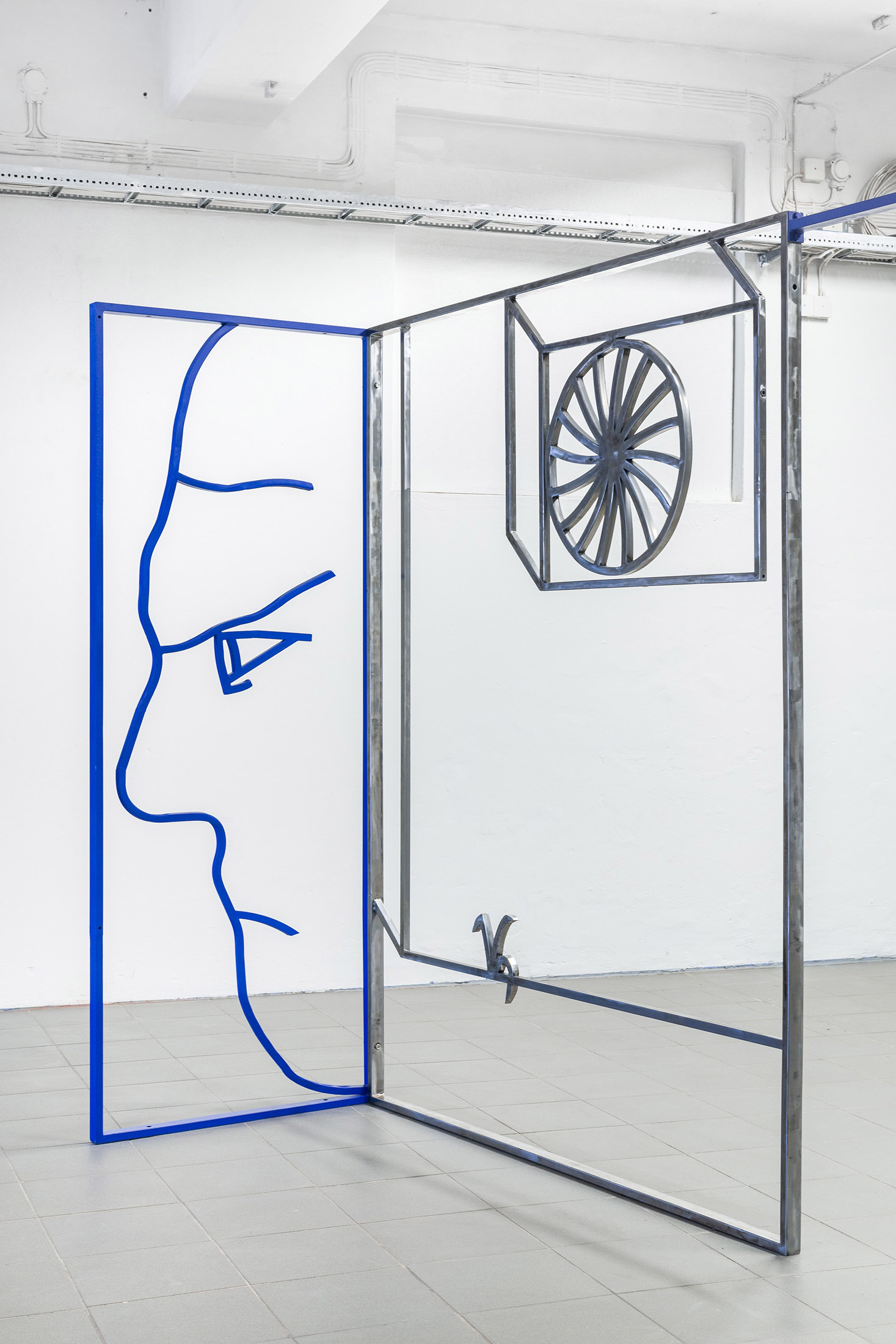

A further air vent exhaust – as well as a scowling, cyclopean face – is constructed from contorted metal tubing and artificially inserted into dominating door frames. The circuitous circulatory and lymphatic system of the industrial animal, cerulean veins carrying deoxygenated blood back to the heart, each bent to the will of Sumari in an architectural reinstatement of the representational. These oversized panels partition the exhibition space, interrupting the eyeline, punctuating the path of any ambulating audience member and blockading any rolling, bench-bound observers (more on them later). Gone is the privacy provided by traditional room dividers, as these sparse silhouettes go so far as to section off space, without screening or obscuring

entirely. Geometric, gridded constructions mirror the institutional or civic nature of the environment they inhabit, the artist always maintaining a keen sense of site-specificity or site-responsivity. Abstracted and flirting with functionality, they form the societal organism’s protective barriers, invariably utilised with the intention to keep out something unwelcome, or lock in something desirable.

Sumari’s artistic interventions even extend to the exterior of the exhibition space, where a strange, humanoid figure sprouts from the stations of the building’s pre-existing bike rack. Our daily use of utilitarian objects is once again called into question when confronted by the enlarged extraterrestrial, its reflective eyes forged from the aforementioned hammered metal. A similar silhouette with lobster-like bifurcated limbs appears encased in another of the artist’s freestanding frames. Crustaceans, aliens and androids aside, this spindly, slenderman shape is in fact the facsimile of a seaweed frond that the artist found over half a decade ago. Resembling a formerly unrecognised gland of the industrial animal’s endocrine system, and known colloquially by such names as bladderwrack, dyers fucus, sea grapes and rockweed (move over pituitary, thyroid or hypothalamus), this sentimental – almost ceremonial – talisman has travelled with Sumari ever since and remains a recurring allegorical or anthropomorphic concern within his practice.

Finally, steel shopping trolleys are given a break from slowly traversing the supermarket aisles, serving the societal organism from within one of its primary sites of quotidian consumption. While previously pushed along by hungry hunter-gatherers, filled to the brim with produce and products in a satiating sweep of the well-stocked shelves, here Sumari has converted those customer crutches into utilitarian, institutional seating. These wheeled benches allow for even the laziest or most lethargic of museum visitors to project themselves around the exhibition, without ever having to leave the confines of their capitalist comfort zone.