An artistic-anarchic DIY vision — as opposed to the production of art works in tightly managed studios, or the complete outsourcing of production processes to industrial methods — is at the center of New Technologies, a duo exhibition of new works by Matthias Groebel and Jean Katambayi Mukendi. For both artists, ‘Open Source’ is the basis of their practice: the production of imaging devices and their painterly output has been Groebel’s work for over 30 years, while the utopian character of Katambayi Mukendi’s work is fed by a desire to produce poetic, speculative models or frameworks.

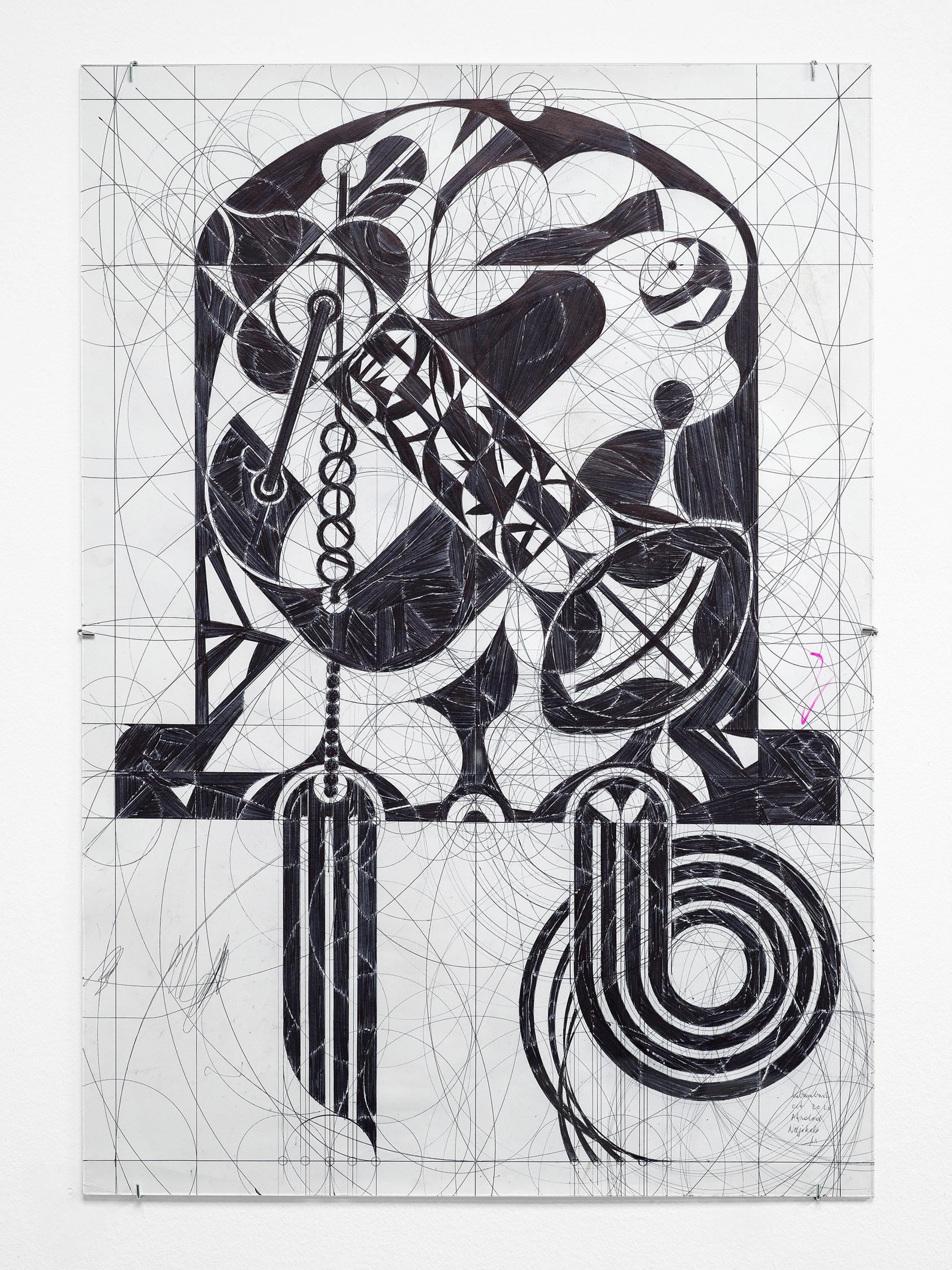

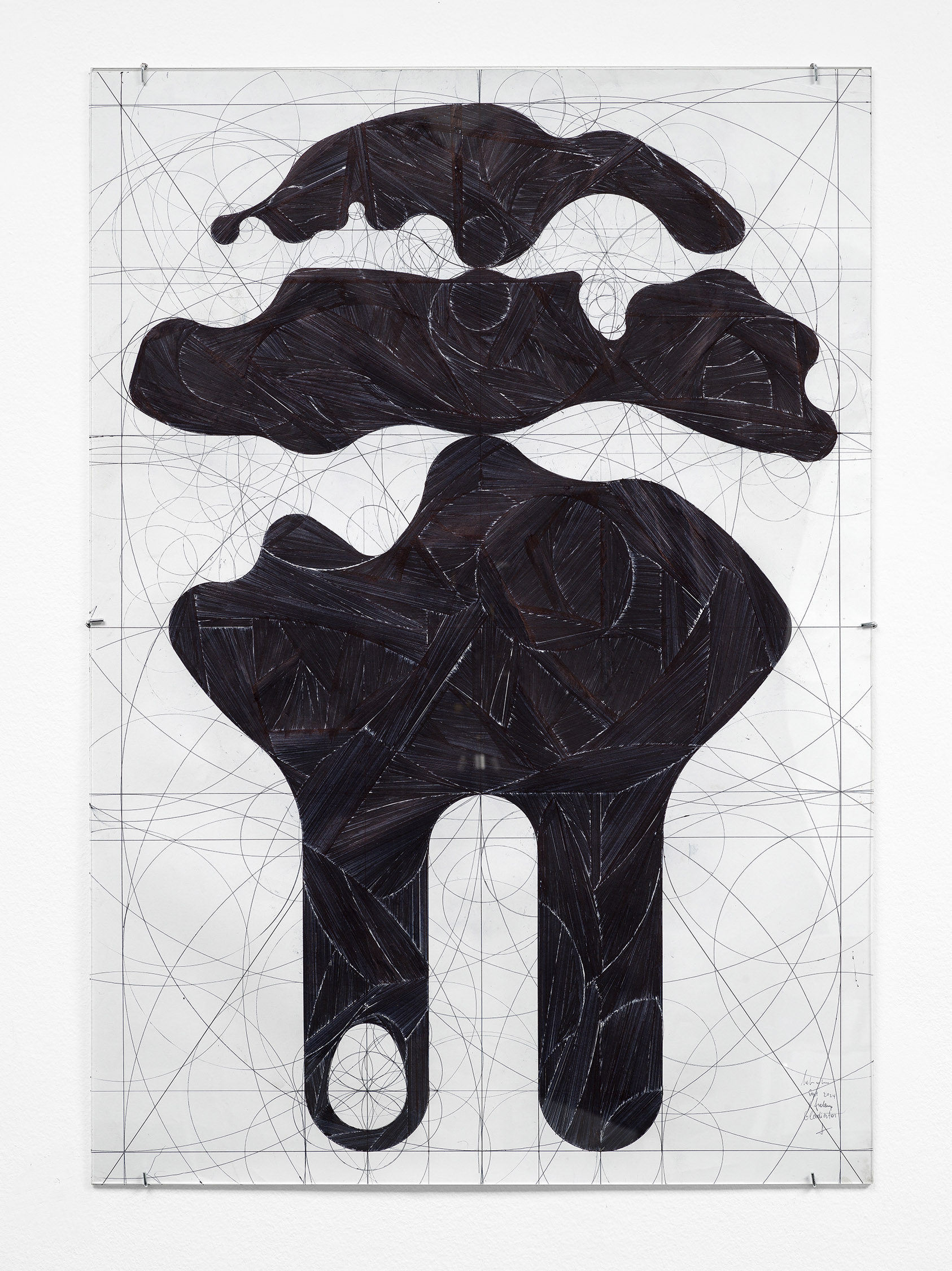

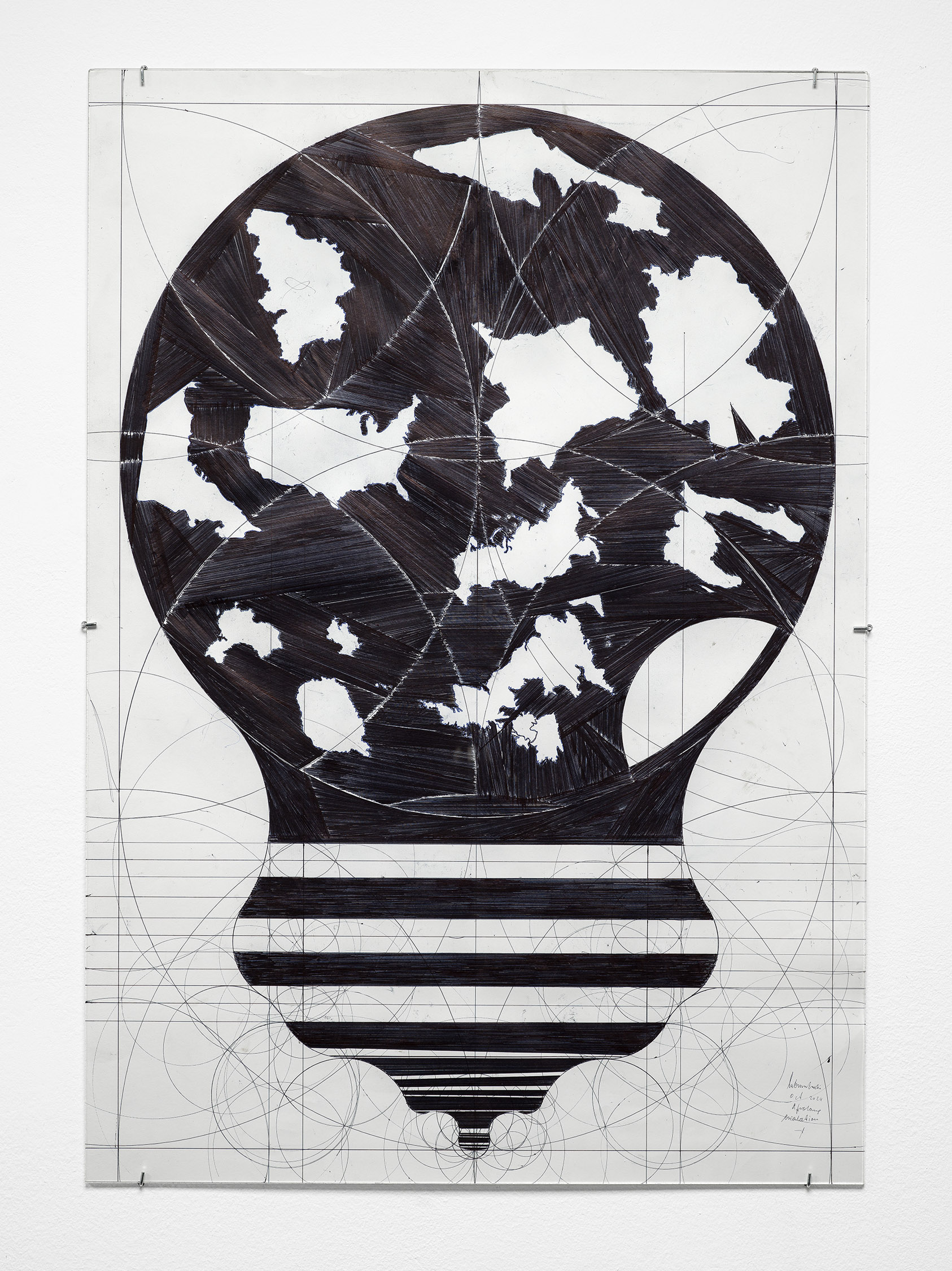

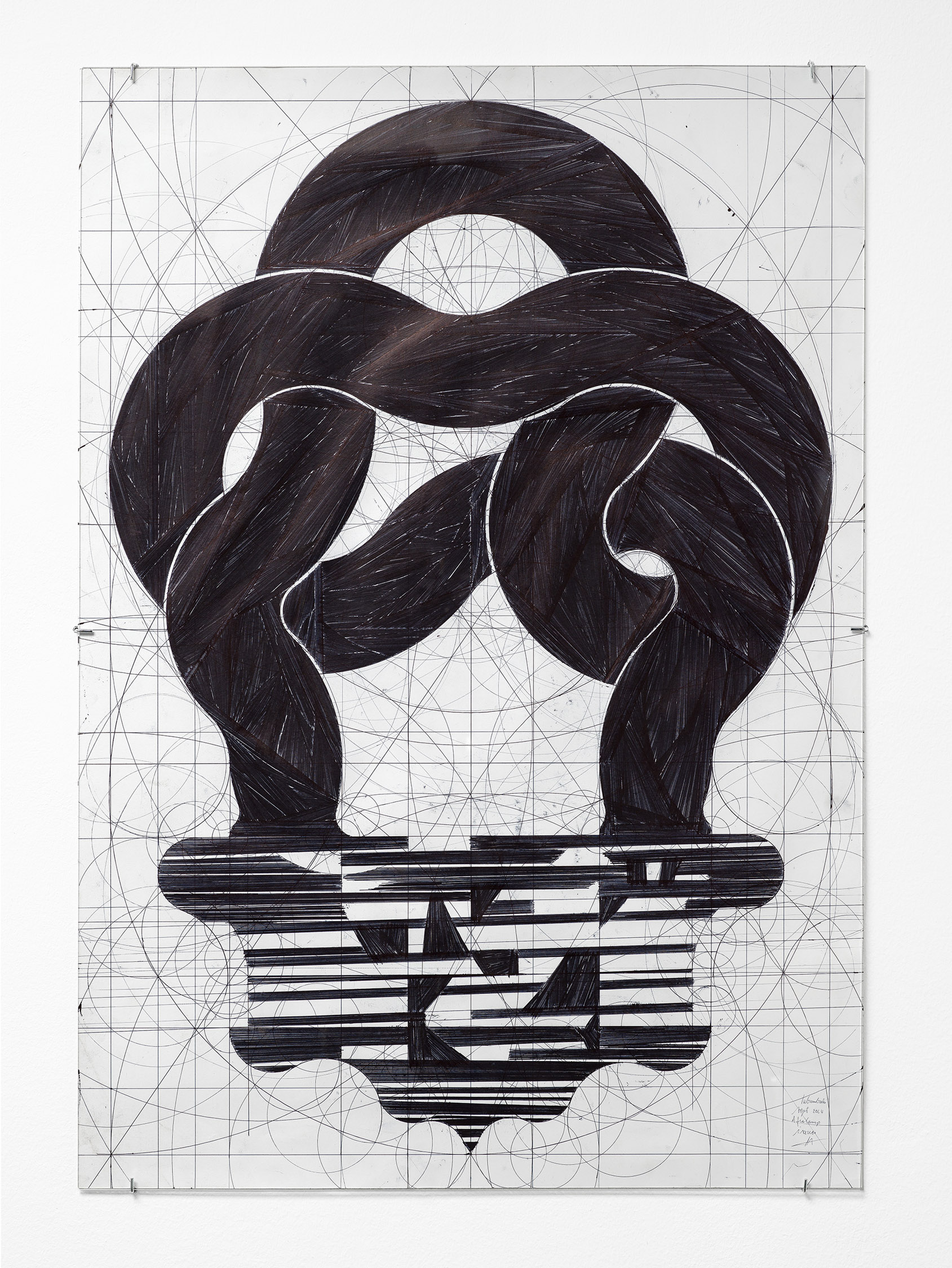

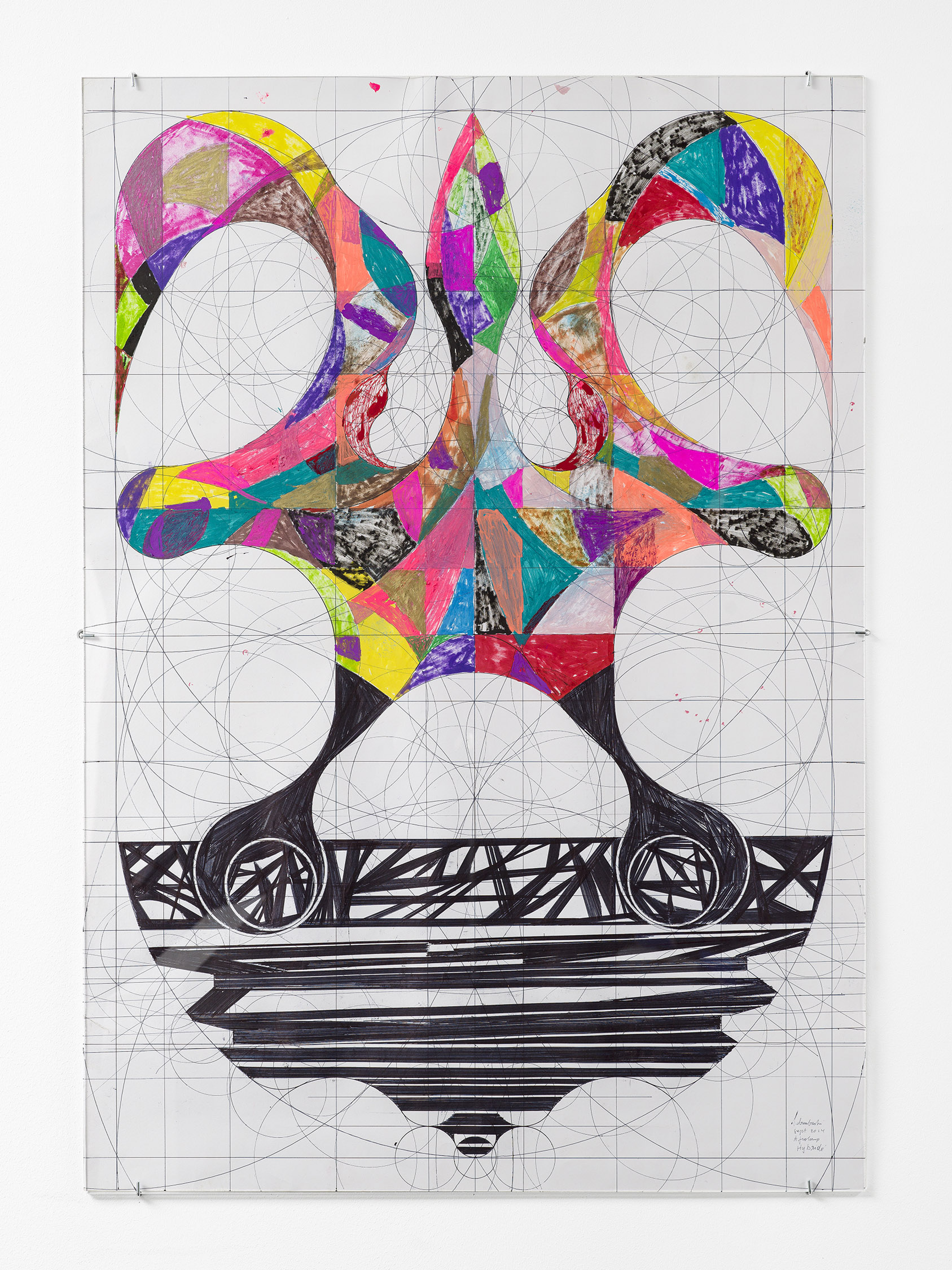

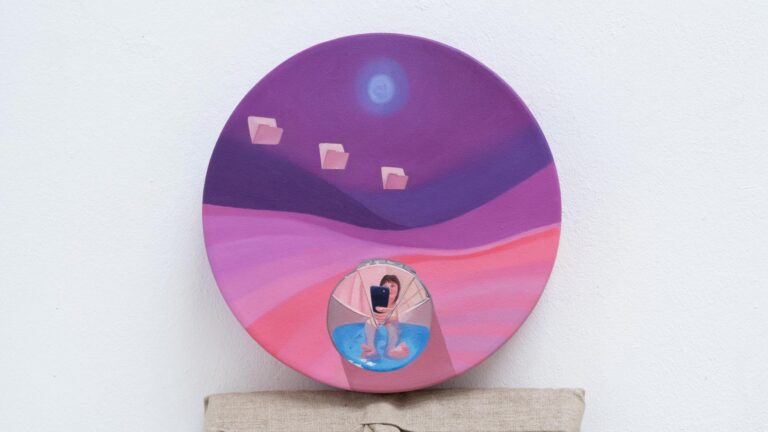

In 2016, Katambayi Mukendi showed his ‘Afrolamps’ for the first time — these drawings of interwoven lines or interlocking surfaces are made on standard paper formats, mostly in black and white and occasionally in color. As hybrids of totemic masks, light bulbs, and maps, they take us back to the 19th century, when, alongside the invention of electric light as a high point of modernist progress, the Congo was being colonized. The consequences of Congo’s colonial history remain tangible, for example in the distortions between local and global energy supply, but Katambayi’s works also insinuate a speculative reflection on the future, which is able to integrate disparate historical lines in a multipolar present.

Trained as an electrical engineer and mathematician, the artist lives and works in his home town of Lubumbashi, the second city of Congo by its economic role and the capital of the Katanga region. His parents were employed by Gecamines, a once state-owned mining company that dates back to the colonial era. Since 2022, around 70% of the world’s cobalt in circulation has come from the Democratic Republic of Congo, most of which is mined in the Katanga region. While the raw material is now an important component in the production of lithium-ion batteries for cell phones and electric vehicles, Katanga itself suffers from an inadequate energy supply, both for private households and industrial extraction processes, as evidenced by constant power outages. Starting from this absurd asymmetry, Katambayi Mukendi’s works revolve around the phenomenon of global energy consumption from scientific, philosophical and art-historical perspectives, linking these with the material realities on the ground.

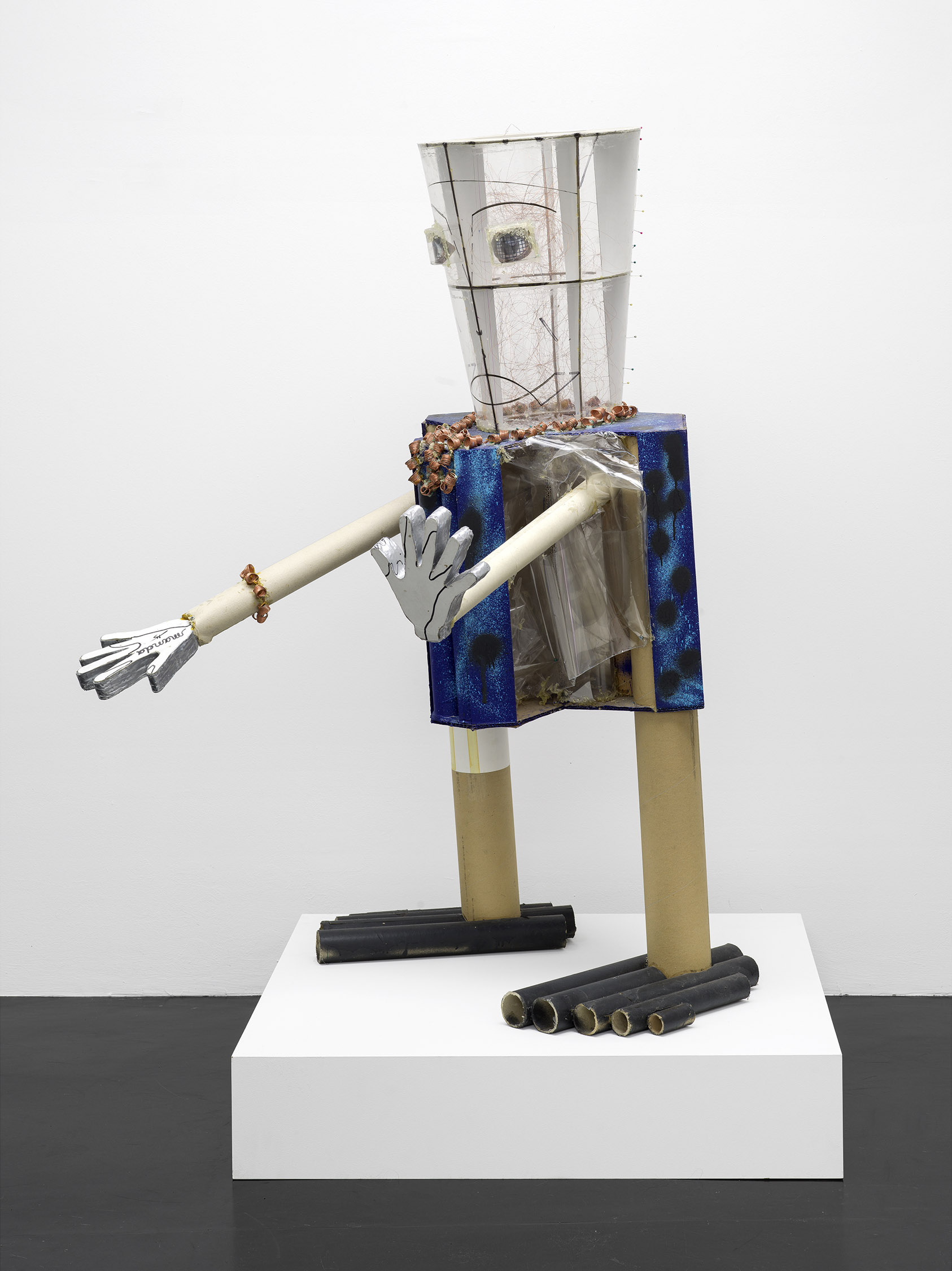

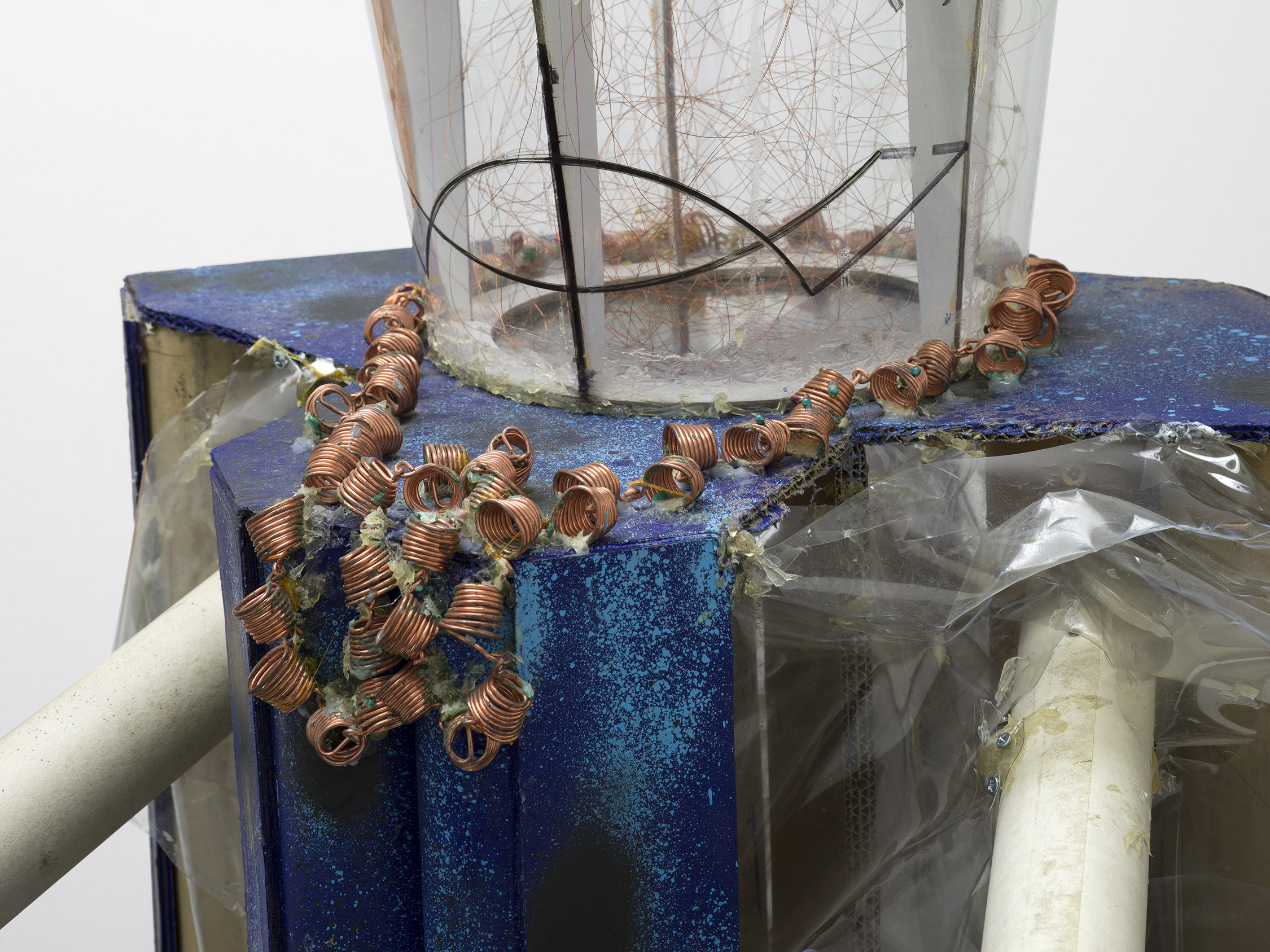

Afrolampe Ndjekele (afroled) (2024), for example, proposes the integration of production waste into research on a less exploitative interpretation of nature, while Afrolampe Deal (2024) traces fundamental dilemmas of the global economy: there are always two poles within a moving field. Afrolampe Illusion (2024), on the other hand, emphasizes the inescapable situatedness of artworks, a fact that Katambayi Mukendi activates through drawing, the oldest form of notation. His drawings are to be understood thus as atlases of his circular thinking, which confronts social and economic imperatives of the colonial era with new universalisms — integrating and speculatively modifying existing notions of engineering, mathematics and other fields of knowledge.

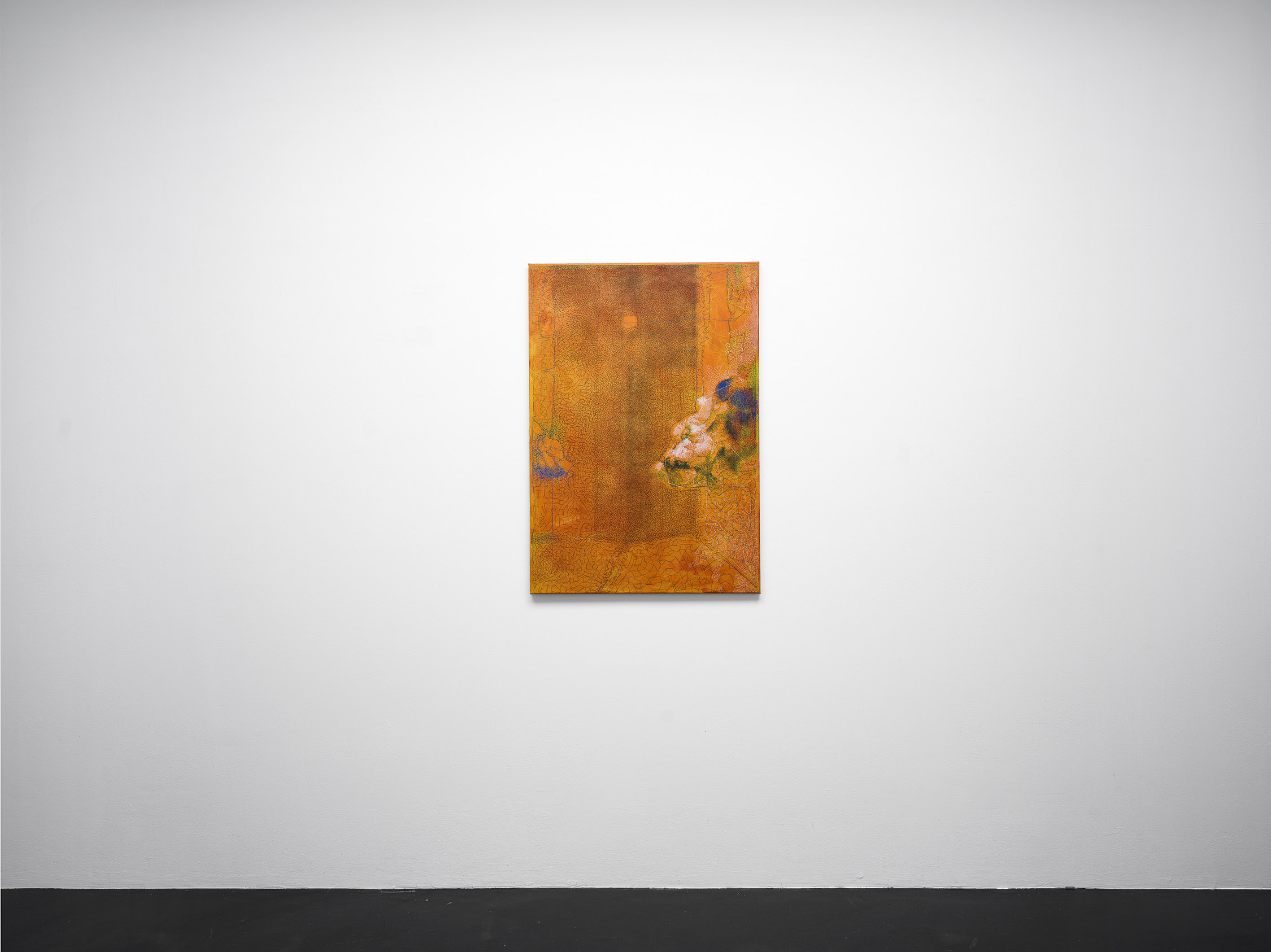

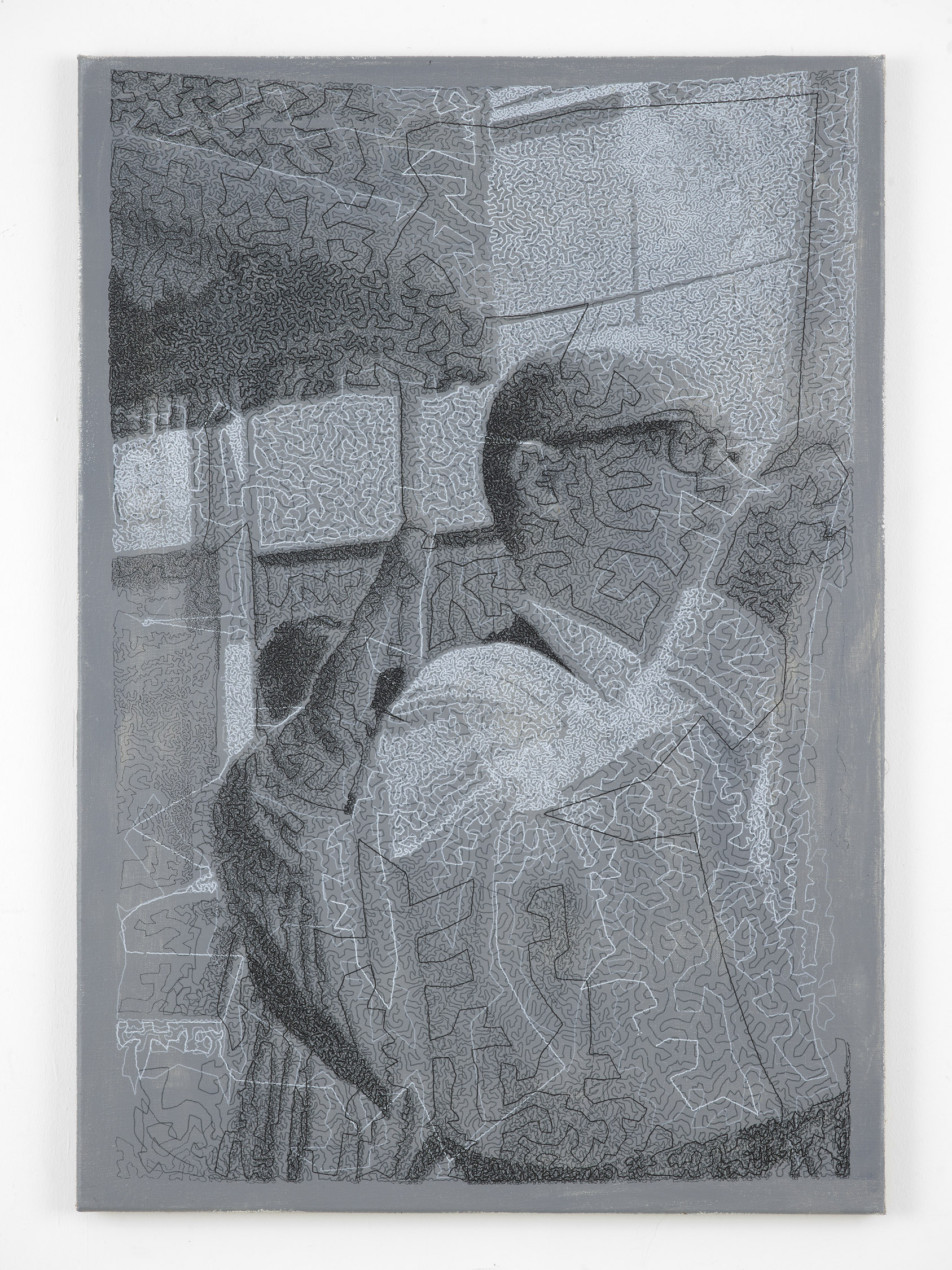

A transformative use of technology is also the starting point for Matthias Groebel and his studio practice. This exhibition shows a new series of works situated between photography, painting and drawing, the creation of which is linked to the now renowned painting apparatus Groebel used to create his paintings from the 1990s and early 2000s with, based on television and video stills. His research into technical developments ultimately led to his construction of a new machine, one that confronts binary parameters such as automation and gesture, digital and analog, painting/ drawing and photography, with a self-reflexive and at the same time media-historical awareness.

Instead of working with television or video images, representative of the period between the 1960s and 1990s, he is now focusing on the history of photography: analog photographs and their technical predecessors of the 18th and 19th century. Groebel’s own analog photographs are now first translated by a scanner into a digital data set and then into a surface consisting of between 20,000 and 50,000 iridescent dots.

He then employs his new drawing machine, which consists of electronic control elements that guide a set of pens. On a primed and roughly painted monochrome canvas, using an algorithm called “The Traveling Salesman“, this machine connects all the defined points without the many colored lines crossing over one another. While in some pictures the source image becomes recognizable, other works are opaque and illegible, the condensed lines and material details coming to the fore. At times, Groebel intervenes manually in the composition of the image, interrupting the automatically running algorithm. The motifs fed into the work are hardly his main interest – rather, they add the option of an extended legibility in neighbouring social fields – carnival, art history or religion. As with the ‘Broadcast Paintings’, they are chosen unintentionally and primarily serve as a new occasion for generating an image.

If we assume that the mathematical algorithm mentioned above also represents a social field, then it primarily stands for process optimization, a principle that has completely infested the current economy now that the endless growth on which Western progress has based its development has reached its limit. So while the physical infrastructures surrounding us are increasingly wearing us down, political and social life is shifting to a “virtual” (mostly powered by lithium batteries from Katanga) that appears ever smoother and more fluid: for example, in the business models that we call “social media“, whose underlying belief in technical innovation is largely disconnected from real social progress.

Against this background, Groebel’s pictures could be read as nonchalant search results, poor pictures, whose privilege over the ubiquitous, supposedly hyper-transparent visual expressions of the present, lies in the structural disclosure of their technical source code. Katambayi Mukendi’s drawings and sculptures, on the other hand, present themselves as technical visions of a cosmopolitan idea of the future, whose universals are conceived on the basis of basic human needs. The work of both artists is linked not only by the line that separates and reconnects the point of departure for each drawing, but above all by a common attitude and the desire for technology on an equal footing.

— Martin Germann

Matthias Groebel (b. 1958, Aachen, Germany) lives and works in Cologne. His work recently has been subject of solo exhibitions at Schiefe Zähne, Berlin; Gathering, London (both 2024); Ulrik, New York (2023); Kunstverein für die Rheinlande and Westfalen, Düsseldorf; Drei, Cologne (both 2022); Galerie Bernhard, Zurich (2021). He furthermore recently contributed to exhibitons at Petzel Gallery, New York; Drei at Bel Ami, Los Angeles; Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne (all 2024); Layr, Vienna; WAF Galerie, Vienna; Francis Irv, New York; Fitzpatrick Gallery, Paris (all 2023); Tonus at La Siri, Asnières-sur-Seine, France; Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn (both 2022); Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, Vaduz (2019). His work is currently part of the 15th Gwangju Biennial, curated by Nicolas Bourriaud (through December 1); Machine Painting at Modern Art, London (through December 14); and the single-work-presentation The Room of Spirit and Time at Empty Gallery, Hong Kong (through November 30). In January 2025, a solo exhibition will open at Modern Art, London.

Jean Katambayi Mukendi (b. 1974, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo) lives and works in Lubumbashi. The most recent solo exhibitions took place at Micky Meng Gallery, Paris (2024); Ramiken, New York (2023); Kunsthalle Kohta, Helsinki; Waldburger Wouters, Brussels; Salts, Basel (all 2022). Furthermore, his work recently has been included in group exhibitions at Kunsthalle, Zurich (2023); The Drawing Center, New York; Milano Triennial, Milano; Congolese Pavilion, The 59th Venice Biennial, Venice (all 2022); Centre Pompidou-Metz, Metz, France; Drei, Mönchengladbach, Germany (both 2021); Taipei Biennial, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taiwan (2020); Gladstone Gallery, Brussels (2018). Current contributions include the Congolese pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennial, curated by Gabriele Giuseppe Salmi; Manifesta 15, Barcelona (both through November 24); and Energies at Swiss Institute, New York (through January 5, 2025).

Martin Germann is Adjunct Curator at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. He lives between Cologne and Tokyo.