Artist: Márk Fridvalszki

Exhibition title: Homeless Between Yestermorrows

Venue: Horizont Gallery, Budapest, Hungary

Date: February 19 – April 1, 2020

Photography: Dávid Biró, all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Horizont Gallery, Budapest

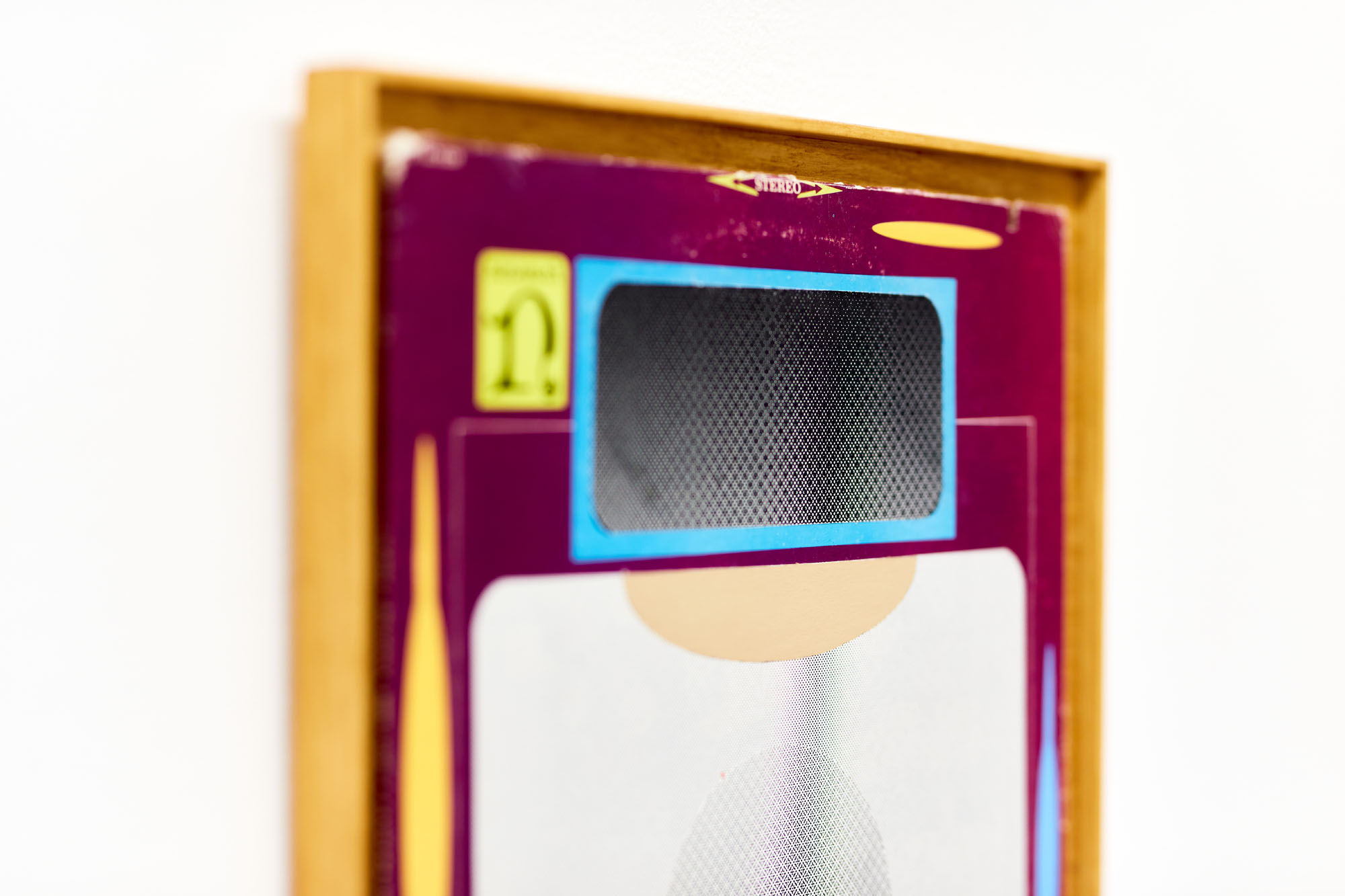

In Homeless Between Yestermorrows, Fridvalszki continues his (an)archeological quest for utopian eras, started in his exhibition series An Out of this World Event, this time penetrating all the way to the deep strata of the sixties and the seventies. Revolutionary designs of the Space Age, abstraction-appropriating album covers, avant-garde jazz improvisations, and other unearthed artifacts of ”Popular Modernism” constitute uncanny collages that strive to fructify our futureless present with critical nostalgia and utopian impulses.

HOMELESS BETWEEN YESTERMORROWS

Text by Barnabás Zemlényi-Kovács

In her essay ”Science Fiction Without the Future”, Judith Berman announced the exhaustion of sci-fi as a means of training the imagination, confronting us with alternate worlds and futuristic scenarios. Most contemporary science fiction, devoid of new utopian drives, only recycles the genre’s established subjects and forms, in other words, the futures of the past. In 2001, when Berman’s symptomatic diagnosis was published, not only did the world of Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey seem more distant than in 1968, but 1968 itself appeared more futuristic than the present day.

Paraphrasing Slavoj Žižek, the exhibition Homeless Between Yestermorrows inverts our arrogant attempts to interrogate the meaning and relevance of the countercultural forces of ’68 and ‘89, the heritage of experimental music from modern jazz to jungle, the sociopolitical ambitions of abstraction or the intellectual-imaginational imperatives of Modernism. Instead, the real question is: what would the rebellious youth of ’68 and ’89, those avant-garde artists and radical philosophers, think about us? In this case, we are not the ones who dive into the past as a means of individual escapism, but it is the past that dives ghostlike into our present. Through their eyes, we must confront our own prosaic, ”post-ideological” age.

In contrast to the ever-expanding spacetime of the Sixties and Seventies, a defining experience of our ageless age is what we can call ”temporal claustrophobia”: a futureless prison of the present, dominated by undead paradigms of the past, from zombie neoliberalism through zombie identity politics to zombie nationalism. Yestermorrow describes this spacetime-trap, a wasteland of the ”out-of-joint time” (Shakespeare), a homeless levitation somewhere between a yesterday that cannot end and a tomorrow that cannot start. Temporal homesickness, embodied in this exhibition, is thus not nostalgic for another time but rather for time itself. It is nostalgia for nostalgia as future-nostalgia or ”postalgia” (Sierk Ybema) that fuelled Modernism and was characteristic of almost all counterculture throughout the twentieth century, which has suddenly become inaccessible, while once productive perspectives are blocked by a pervasive counter- or ”formal nostalgia” (Fredric Jameson). If space was annihilated by time during the age of industrial capitalism, as Marx predicted, then post-industrialism brought the annihilation of time by space. According to Lars Bang Larssen, what died in contemporary culture is death itself: as there is no future that could make the past past, it recycles in retro-circles and postmodern pastiches. Without temporality, there is no anachronism.

Revolutionary designs from the Space Age, abstraction-appropriating album covers, avant-garde jazz improvisations, and other unearthed artifacts of ”Popular Modernism” (Mark Fisher) in this seemingly timeless and spaceless white cube not only bring 1968 into uncanny proximity but Space Odyssey too; more precisely that half-hypermodern, half-neoclassic hotel room, in which the protagonist, space traveler David Bowman is locked by extraterrestrial agents: a sterile space, both futuristic and anachronistic, where Bowman could die and be reborn in order to set the ”out-of-joint time” right again. Likewise, Fridvalszki’s avant-garde desire is to “go ’back’ to a time when there was still a ’to come’”. With Modernism’s utopian impulses and imagination-catapults, he strives to break the infinite loop of timelessness, to finally return to the future. In the age of temporaphobia, temporaphilia is our most effective weapon.

Thanks to András Leidál (Saint Leidal The 2nd), Péter Lowas (LOWAS WORKS) and Martin Segesdi.