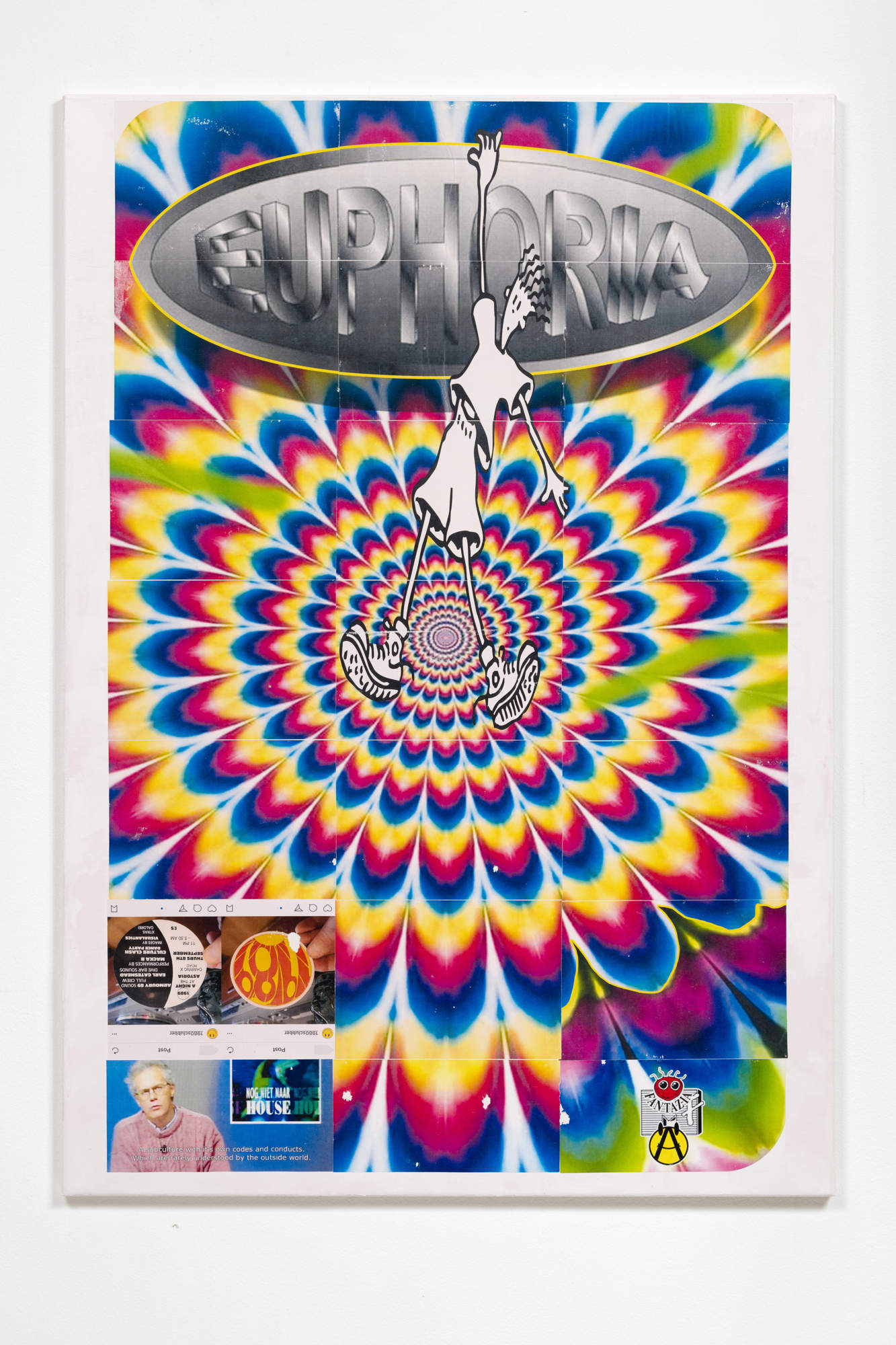

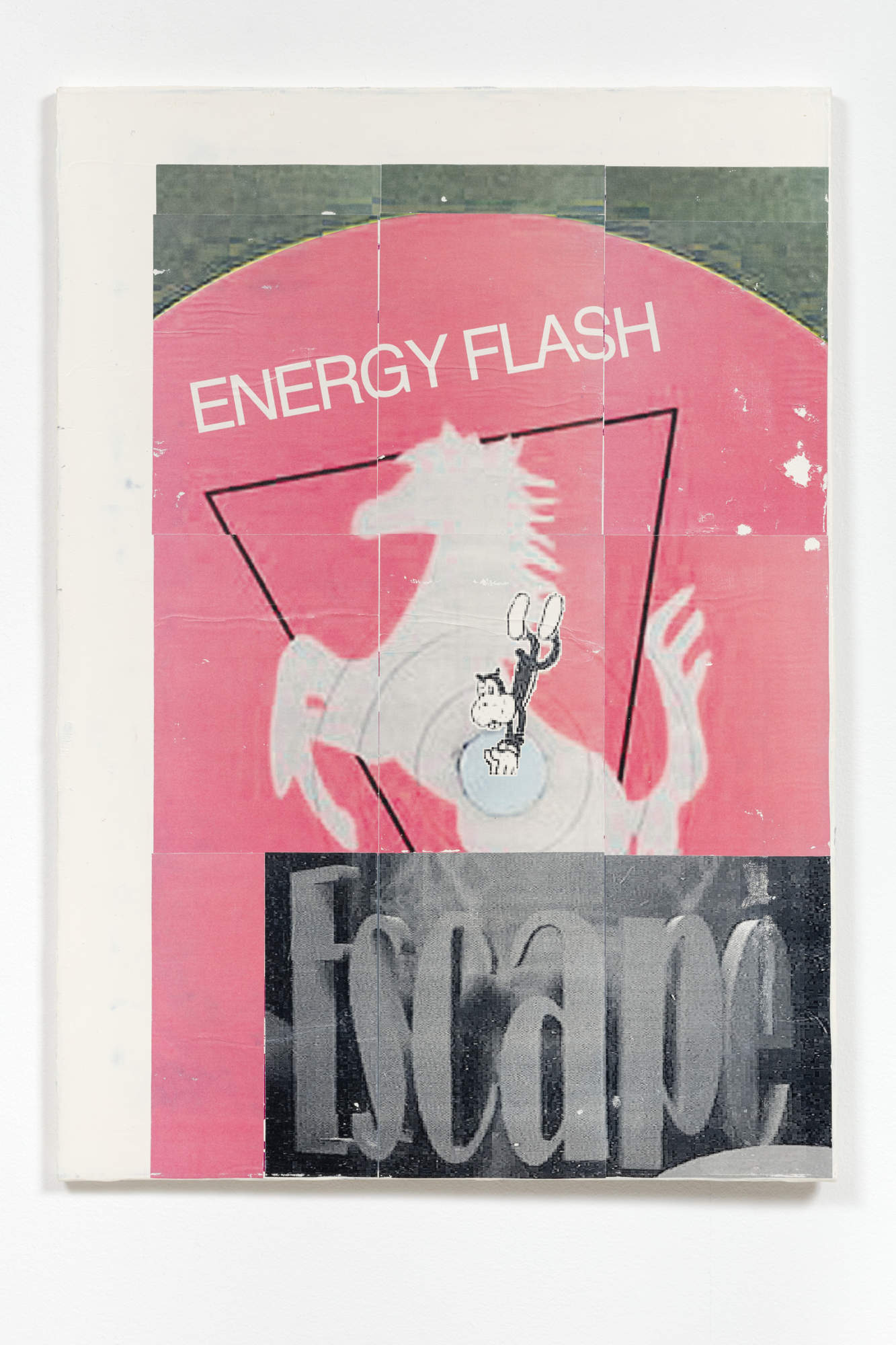

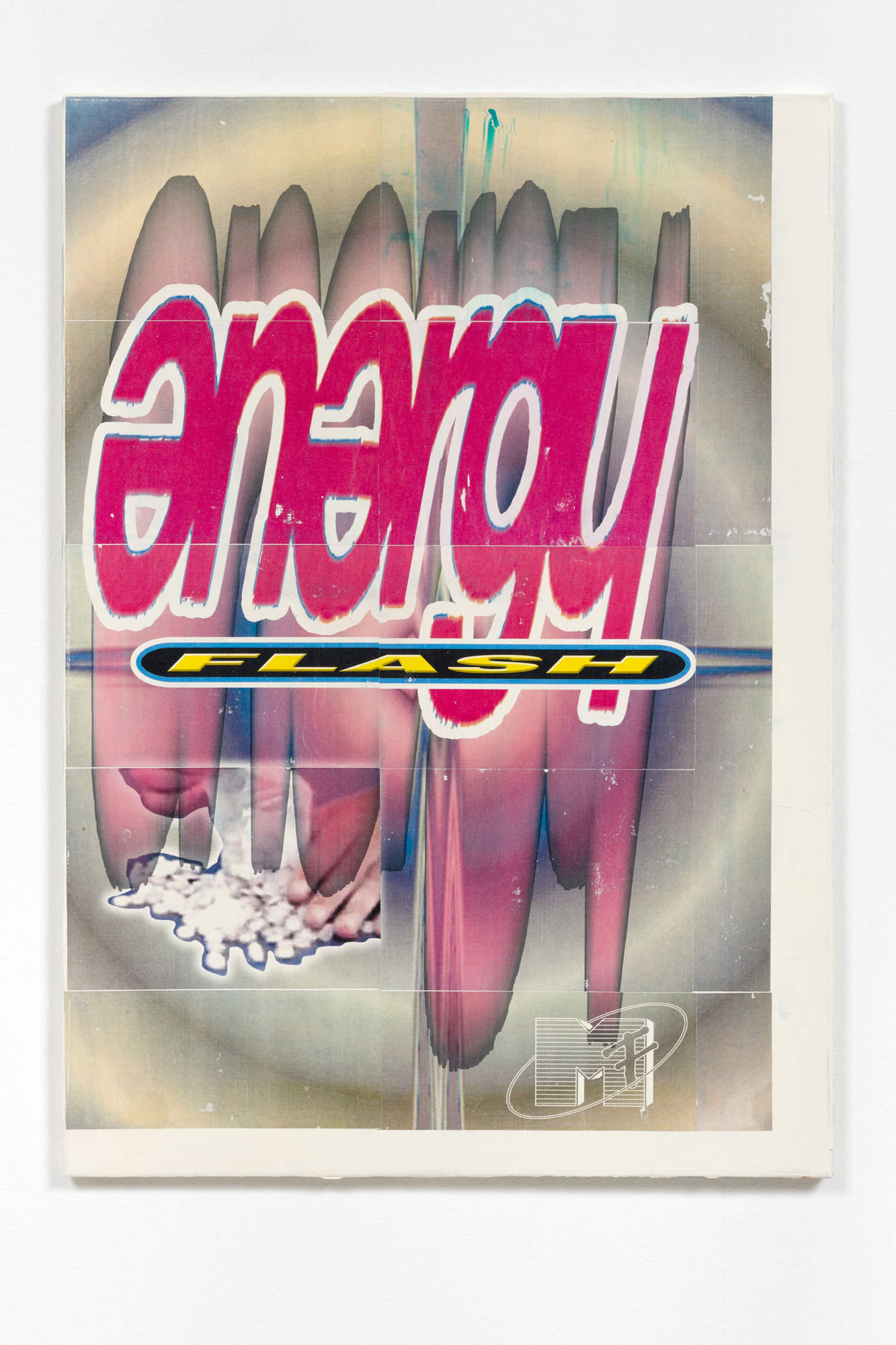

Artist: Mark Fridvalszki (Featuring Aleksandr Delev and Zsolt Miklósvölgyi)

Exhibition title: An Out of this World Event IV

Venue: Horizont Gallery, Budapest, Hungary

Date: March 14 – April 10, 2019

Photography: Dávid Biró, all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Horizont Gallery, Budapest

E is for Endgame

20th of May 1967, Montreal, Canada. Early afternoon during structural renovations, a fire burned away the transparent acrylic bubble of the geodesic dome called Biosphere designed by Buckminster Fuller. Giant smoke clouds were evaporating into the air.

The Biosphere building on St. Helen’s Island, the former pavilion of the United States, was supposed to represent an optimistic and holistic approach towards the planet where nature and technology are inseparable from each other. This ideal image of the building also embodied a certain utopist optimism in a cosmic architectural scale. With the chemical compounds of the plastic elements of Buckminster Fuller’s dome, the promises of a brighter and harmonious future have also burnt away.

But utopia, as McKenzie Wark argues in his essay entitled ‘Renotopia’, is still alive and well, it’s just gotten very small. In the fourth edition of his exhibition series ‘An Out of This World Event’, Mark Fridvalszki aims to point out how utopia has shrunk both in time and space. He suggests that by the early 90s, the countercultural energies, as well as the ambitious and imposing utopist visions of the 60s and 70s, have fled to and condensed into the euphoric moments of the acid rave subcultures. Through various installations, happenings, printed materials, and collaborative works, he draws up an impressive panorama of various optimistic futurities from the past.

But Fridvalszki’s art doesn’t want to create a positivist historical genealogy where past, present, and future are part of a causal chain. Instead, his artworks are part of a larger techno-archeological assemblage where various time planes exist together in a compressed form. ‘An out of This World Event I-IV.’ was so far his most profound artistic attempt to show how contemporary culture is shredded between the never achieved, preceding visions of lost futures and the continually narrowing horizons of utopistic moments.

In that regard, Fridvalszki’s art can be related to Mark Fisher’s diagnosis of our futureless contemporary conditions. As Fisher argues, “(w)hile 20th-century experimental culture was seized by a recombinatorial delirium, which made it feel as if newness was infinitely available, the 21st century is oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion. It doesn’t feel like the future. Or, alternatively, it doesn’t feel as if the 21st century has started yet. We remain trapped in the 20th century…” Indeed sometimes it feels like as if we were trapped in a chess endgame where only a few pieces left on the board repeating the exact same strategic pattern over and over. This is what Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi in his book entitled ‘After Future’ calls as “the slow cancellation of the future” that started during the 70s and 80s.

It’s almost ironical how the process of the slow cancellation of the future coincides with the ever-accelerating speed of the ecstatic beats of the 90s rave culture. But the more inconsolably we immerse ourselves into the instantaneous euphoria of rave-optimism, the more inevitably will look like the disappearance of the future on the other day. And that’s exactly why Fridvalszki’s party-hauntological diagnosis also implies a cultural critique, as the ceaseless craving for “an out of this world event” is an unequivocal symptom of a world without any future.

Zsolt Miklósvölgyi, 2019