On Friday, September 27, the solo exhibition “Dear Diary… Layers of Dreams” by artist Marina Mesar OKO opened at Trotoar Gallery in Zagreb.

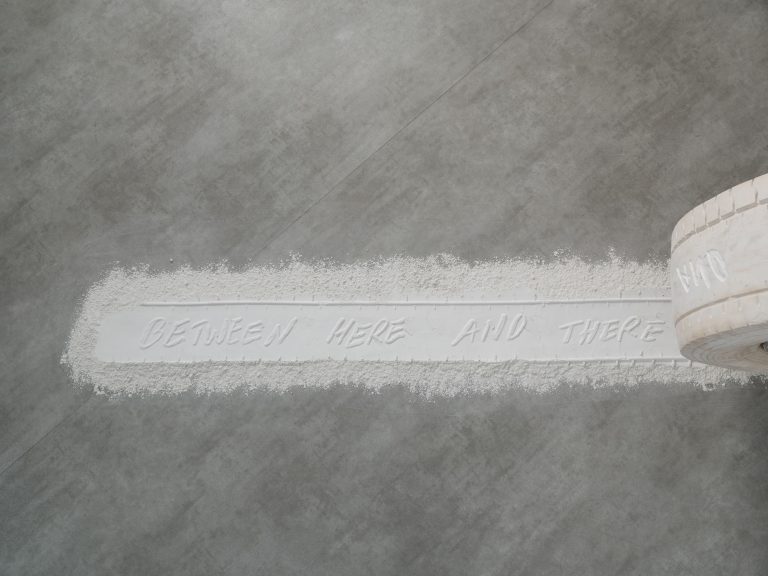

After seven years, OKO returned to the Zagreb art scene with a solo exhibition of entirely new works, exploring her own memories, identity, and the intertwining of the imaginary and real worlds. The title of the exhibition, “Dear Diary: Layers of Dreams,” suggests an intimate journey through layers of the inner world and sets a conceptual framework of constant introspection. Using the metaphor of diary writing, OKO expresses the continuity of her creative process, where each new exhibition represents the next chapter in that diary, inviting the audience to create their own interpretations. In addition to her signature drawings of animals in human form, which explore archetypal roles of protectors and strength, OKO presents new works and experiments with various media in this exhibition. A site-specific installation, including wall wallpapers, photographs, and digital collages printed on silk, reflects a process of self-exploration and contemplation on identity, life changes, and the power of daydreaming. The exhibition’s themes are deeply rooted in the transition from childhood to adulthood, especially within the context of the social changes that marked her upbringing.

***

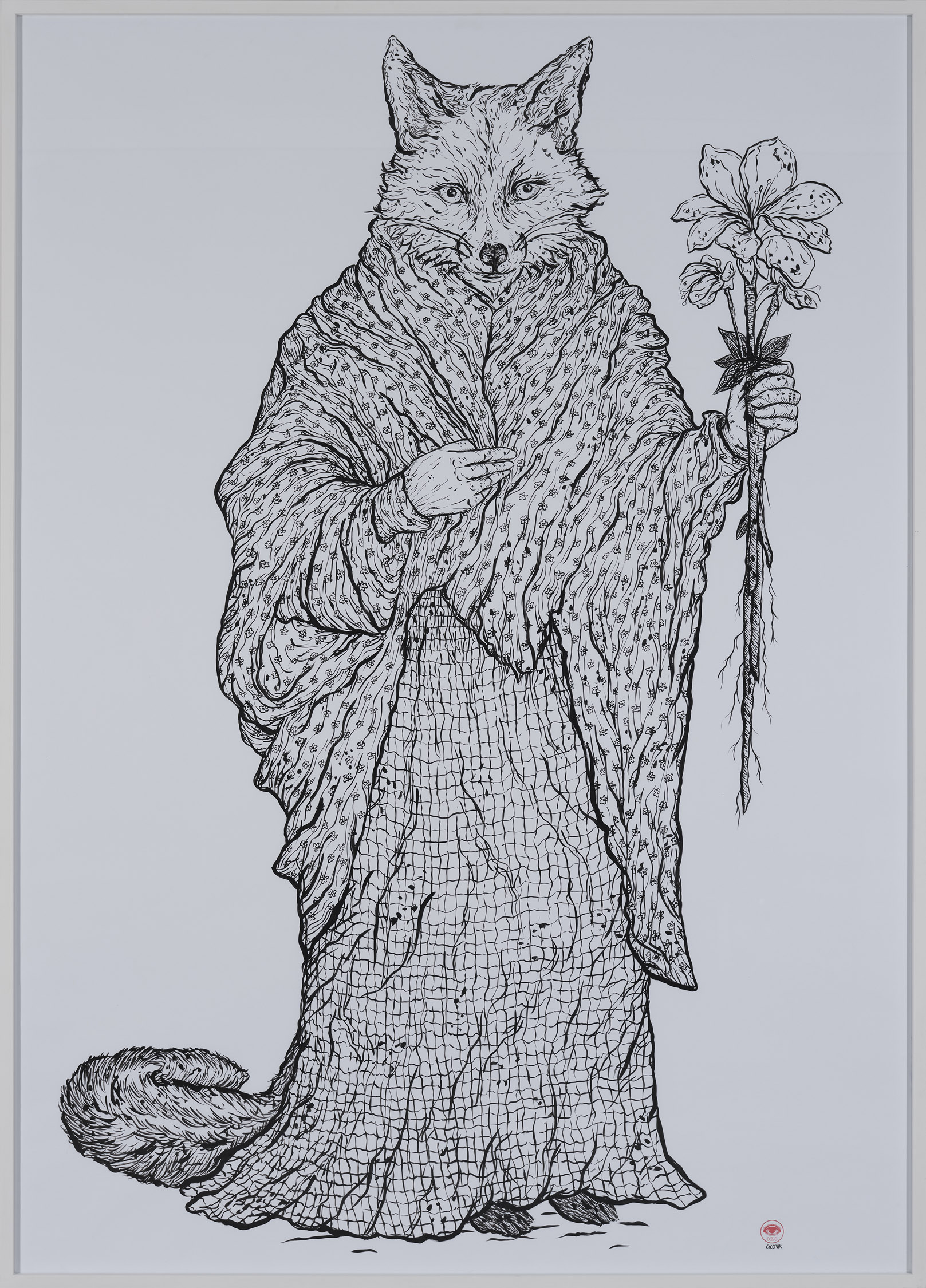

Scenes in the installation by Marina Mesar (better known as Oko), conceived for the Trotoar Gallery in Zagreb, range from a photograph of her grandmother’s kitchen, positioned like wallpaper, to the artist’s emblematic, framed two-metre drawings of animals dressed in human garments, reminding me of Walter Benjamin’s essay written in 1934 for the tenth anniversary of Franz Kafka’s death. Benjamin concludes that Kafka’s ancestral world, as unfathomable as reality, was profoundly important, and that it was this world that led him to the animals that, in his work, as receptacles of the forgotten, are endowed with the greatest opportunity for reflection.

When Marina talks to me about her unusual animals, she explains that it is a child’s imagination that depicts people’s protectors in the form of animals. This “confession” leads me to another writer dear to me, Philip Pullman, in whose trilogy His Dark Materials the human being is vitally inseparable from his animal companion – the dæmon. Pullman’s dæmon is said to be inspired by Renaissance portraits – da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine and Holbein’s Lady with a Squirrel. In Marina Mesar’s depictions of animals, the idea of a receptacle of the forgotten is articulated through a drawing execution that clearly connotes some past historical period. Specifically, it is impossible not to notice the reminiscences of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland illustrations made by John Tenniel in the mid-19th century, or Grandville’s caricatures from the same period, in which the animal form mocks the characters of human protagonists. However, although occasionally referencing the cuts of the then-fashionable bourgeois garments in which Grandville dressed his characters, Marina Mesar radically changes the meaning of animal depictions – there is nothing threatening or repulsive in their facial expressions. On the contrary, from the tiniest ones that discreetly appeared some twenty years ago as barely noticeable paper stickers on dilapidated façades in Zagreb’s Lower Town, to the gigantic ones in Oko’s later murals, these strange creatures, devoid of irony and cynicism, call for a different perception of the city and one’s own existence in it, producing a soothing effect. At the beginning of the industrial age, Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard adopted the name Grandville, which literally means “metropolis”, and used speciesist allegory to visualize the human traits that would lead to the current dystopian state. Two centuries later, in Zagreb’s urban dystopia, Marina Mesar intends her wise and benevolent animals to protect people from themselves. And she chooses the name Oko (Eye) for herself. What is that eye gazing at? The place of origin of these images? And where is that place?

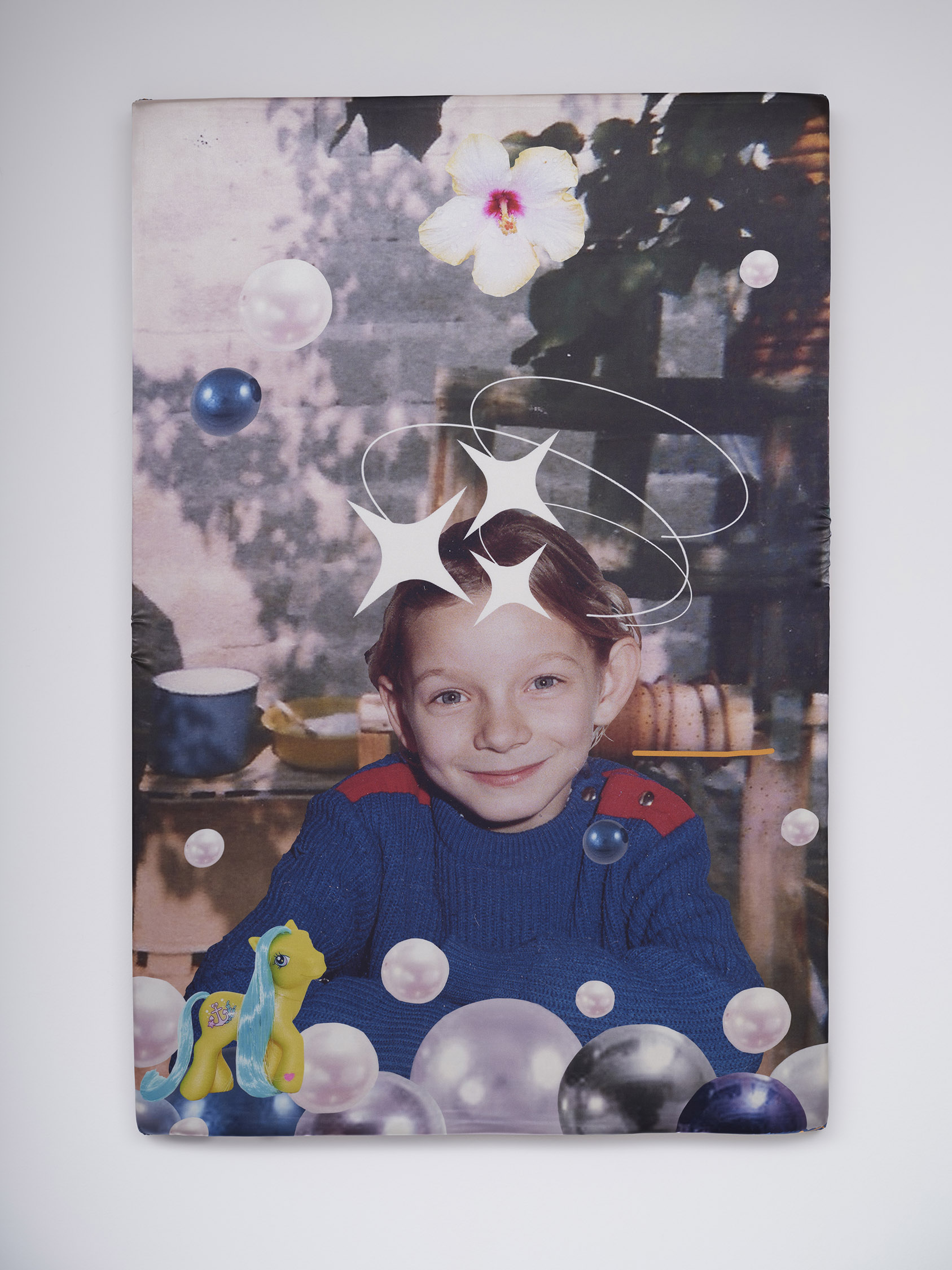

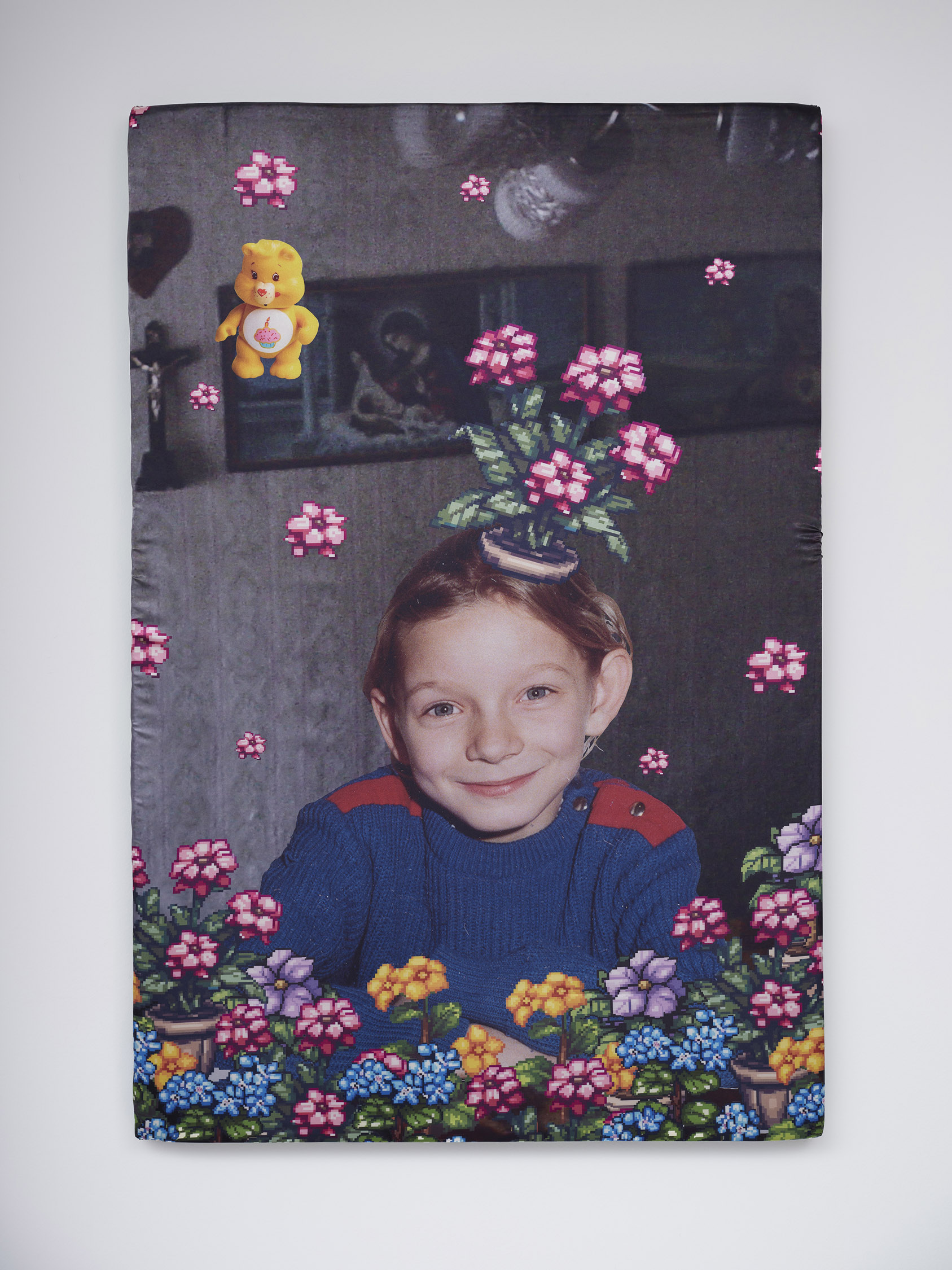

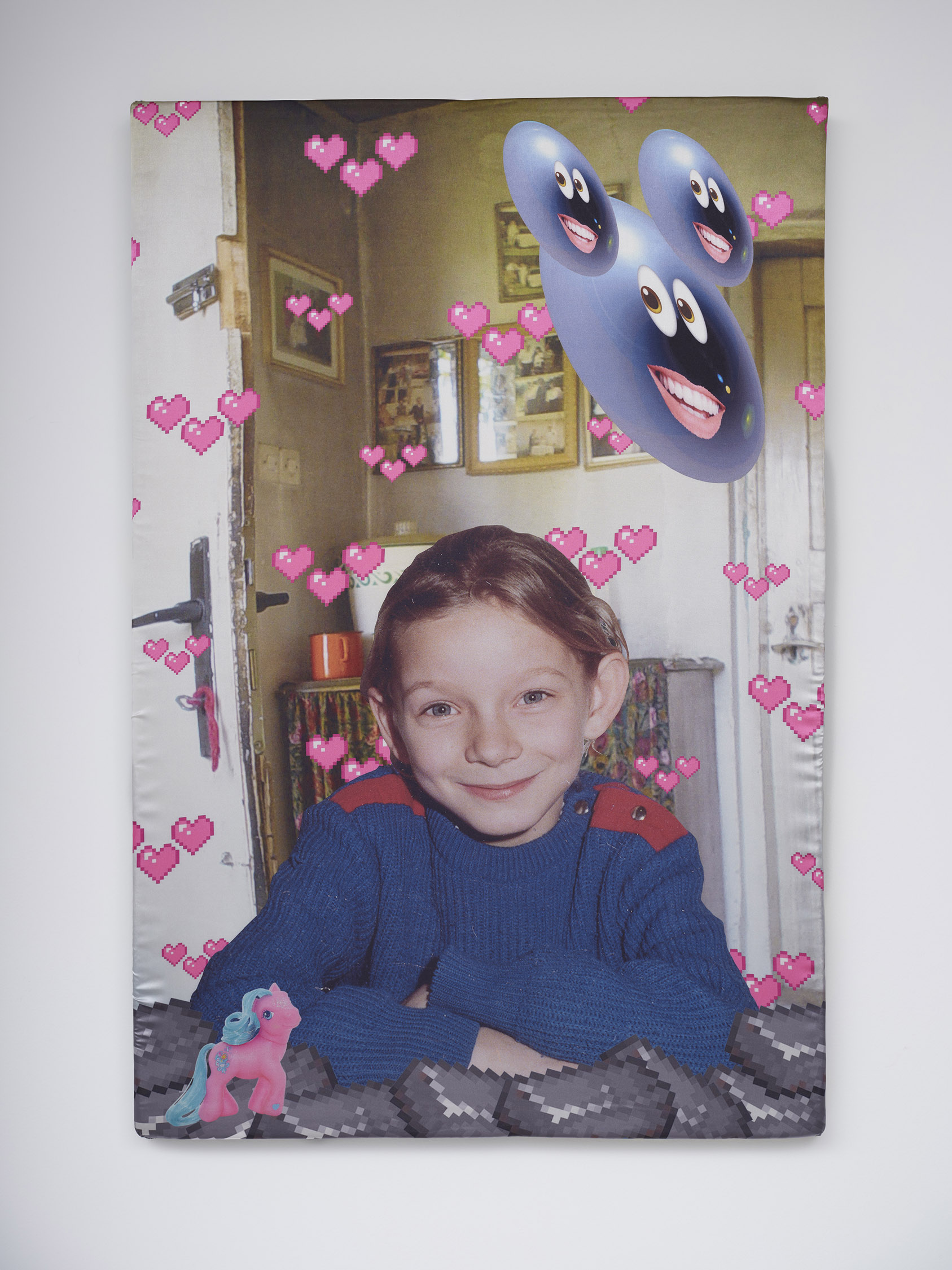

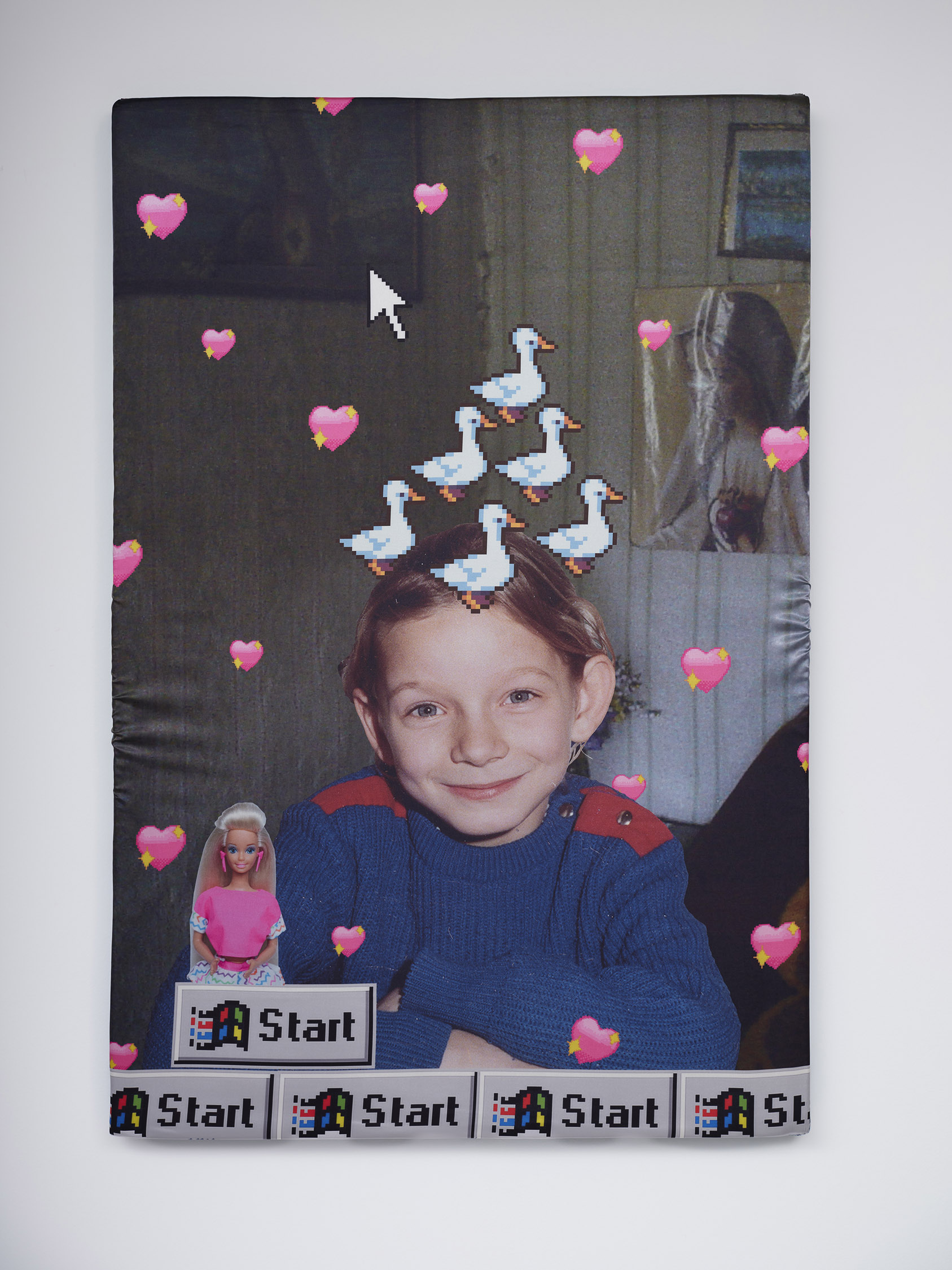

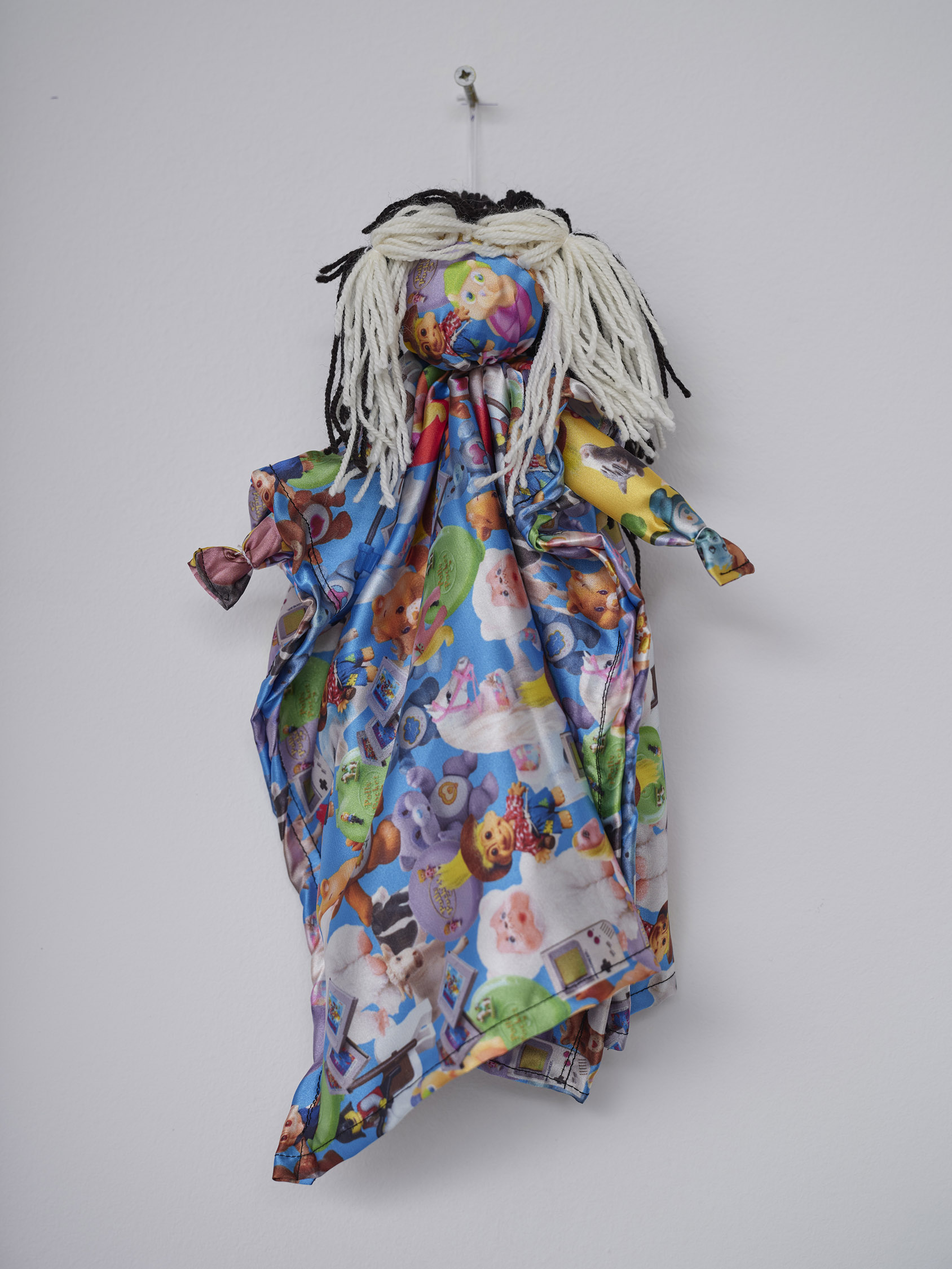

In Oko’s exhibition titled Dear Diary, a photograph of her grandmother’s kitchen functions as a mise-en-scène for the proliferating images and tangible objects that embody them. In that photograph, as well as in other places within the gallery space, the artist has hung many small rag dolls, identical in shape, which she made with her own hands. They are a reminder of a bygone time and the place of origin of the images that she would articulate years later with her precise drawings, which, among other things, call to mind drawings from 18th-century natural history manuals. The grandmother, whose absence is clearly emphasized in the photograph of the kitchen, was the one who used to make rag dolls for the little girl and taught her to make them herself. The child’s smiling yet wistful face gazes today at the so-called artistic audience from the pictures-objects exhibited at the Trotoar Gallery with the same gaze she directed at the camera lens while sitting at her elementary school desk. Looking into the device that is also a social apparatus, and which produced her image. Many years after the shooting of that photograph of the child at her school desk, a media image has been created of the internationally recognized artist Oko, indispensable in the field of street art, whose exhibition Dear Diary calls for reflection on the sensory textures that exist in the invisible deposits beyond every visible image.

The narrative backbone of the Dear Diary installation is defined by the dynamics of the difference between a handmade rag doll and an industrial, mass-produced toy, or, if we will, between a unique, manually produced image and an infinitely reproducible, technologically generated one. Thus, the difference in the production technology of the child’s toy also marks a class difference. Namely, at the end of the 20th century, when the analog photograph was taken, the portrait of a girl at a school desk, which would multiply and metamorphose in reproductions inhabiting each of the exhibited soft pictures-objects by Marina Mesar-Oko, there was hardly any schoolchild who did not own one of the serially produced toys that were readily available in shops. Marina was one of those rare children. While others had them in abundance, the little girl in the photo fantasized about them. That is why, like in a comic book or an animated film, images of those toys appear as apparitions floating around her figure recorded in a photograph from her childhood. However, in the pictures that articulate the Dear Diary installation, this portrait is dislocated – the classroom has been erased, and little Marina is sitting in her grandmother’s kitchen, not at a school desk. In contrast to the time when the child used to sew herself dolls from used fabrics, the artist now has information technology at her disposal, which allows her to materialize the visualization of a child’s longing. Thus, in the Dear Diary installation, rag dolls similar to the ones she made in her childhood appear, sewn from silk featuring a printed pattern of industrially produced toys, images of which the girl from the photograph used to cut out from second-hand print catalogues of the time. Her photographic portrait, blending with the images of what she fantasised about, is also printed on silk fabric, stretched over a rectangular sponge block instead of a blind canvas frame. Such materialization of image emergence requires not only vision, but also haptic perception – to feel the smoothness of the silk and the softness of the support covered by the image. Because Dear Diary, with its series of enigmatic signifiers, which we can call images of children’s toys, refers to a living bodily experience. And despite the undoubted iconic heterogeneity, the toy images completely saturate the silk fields from which they emerge, same as the enigmatic tattoos inscribed on the skin of the artist Oko.

Leonida Kovač

Marlera, August 2024