Artist: Magnus Frederik Clausen

Exhibition title: Work

Venue: Braunsfelder, Cologne, Germany

Date: November 17, 2022 – February 11, 2023

Photography: All images are copyrighted and courtesy of the artist and Braunsfelder, Cologne

As an entrepreneur, Magnus Frederik Clausen can’t be trusted

by Dr. Larissa Kikol

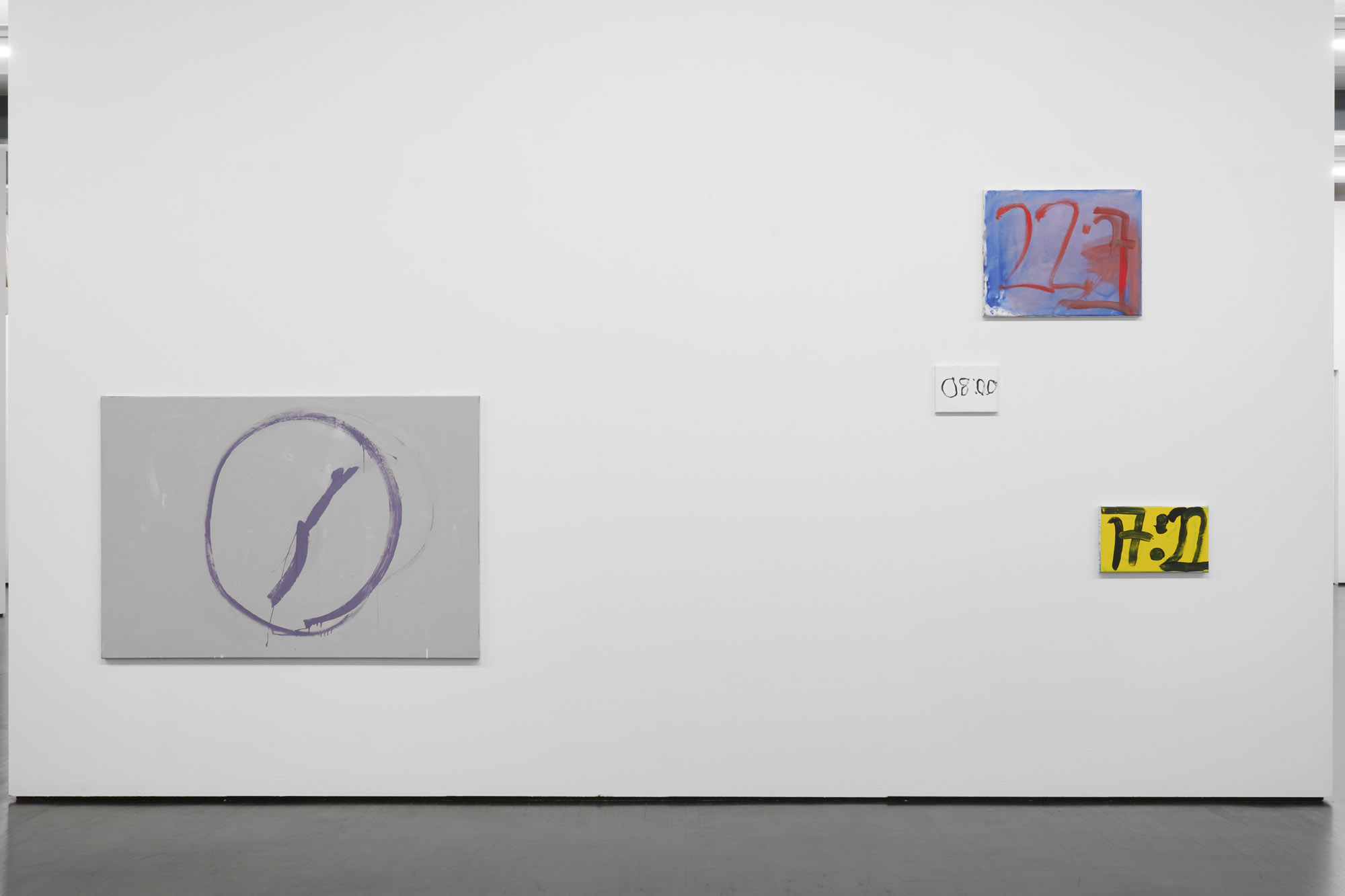

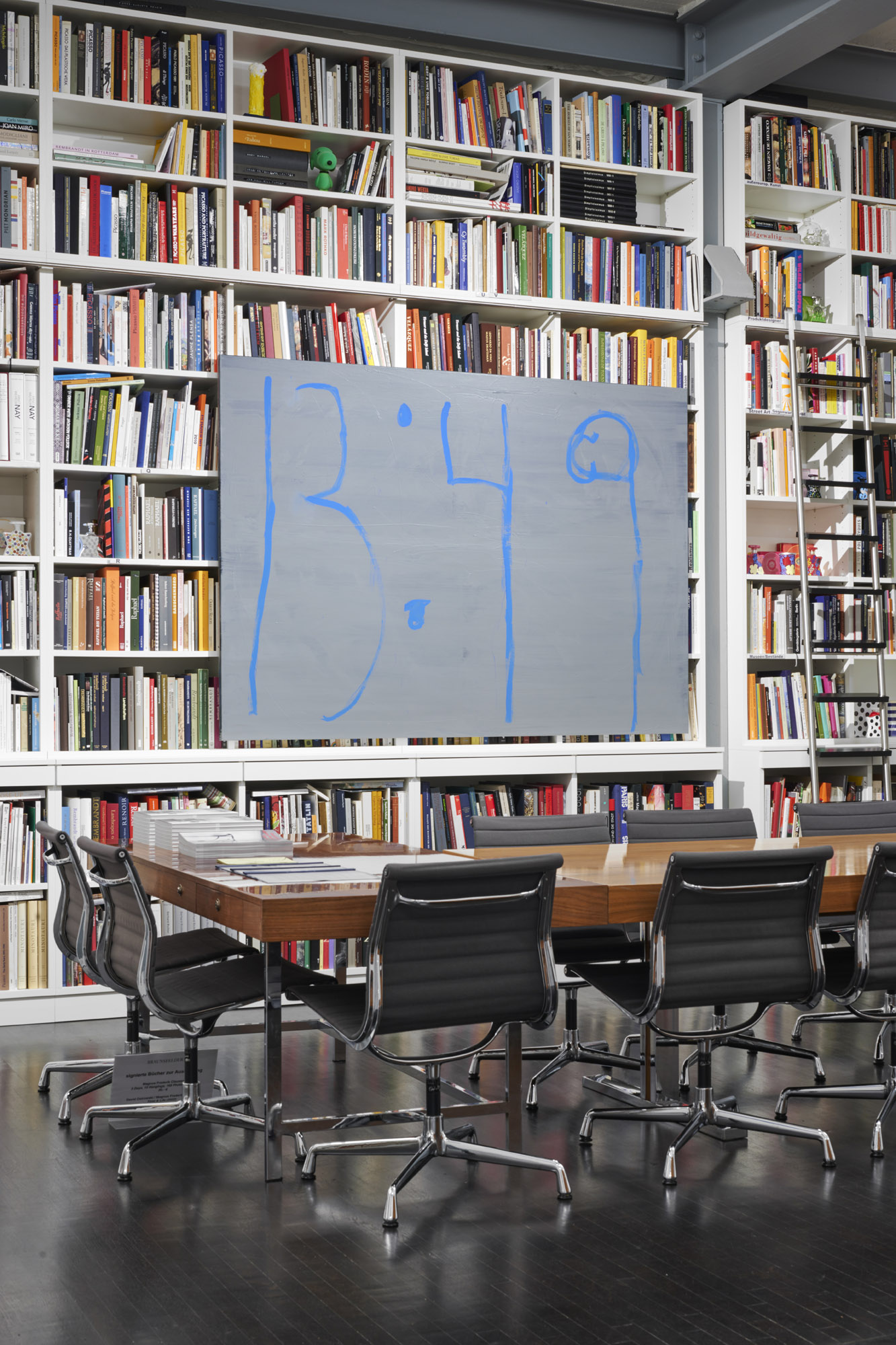

Braunsfelder is pleased to present Work by Magnus Frederik Clausen. After C.C.C., Copenhagen, and Class Reiss, London, this is the third time paintings from the clock series are shown in a solo presentation.

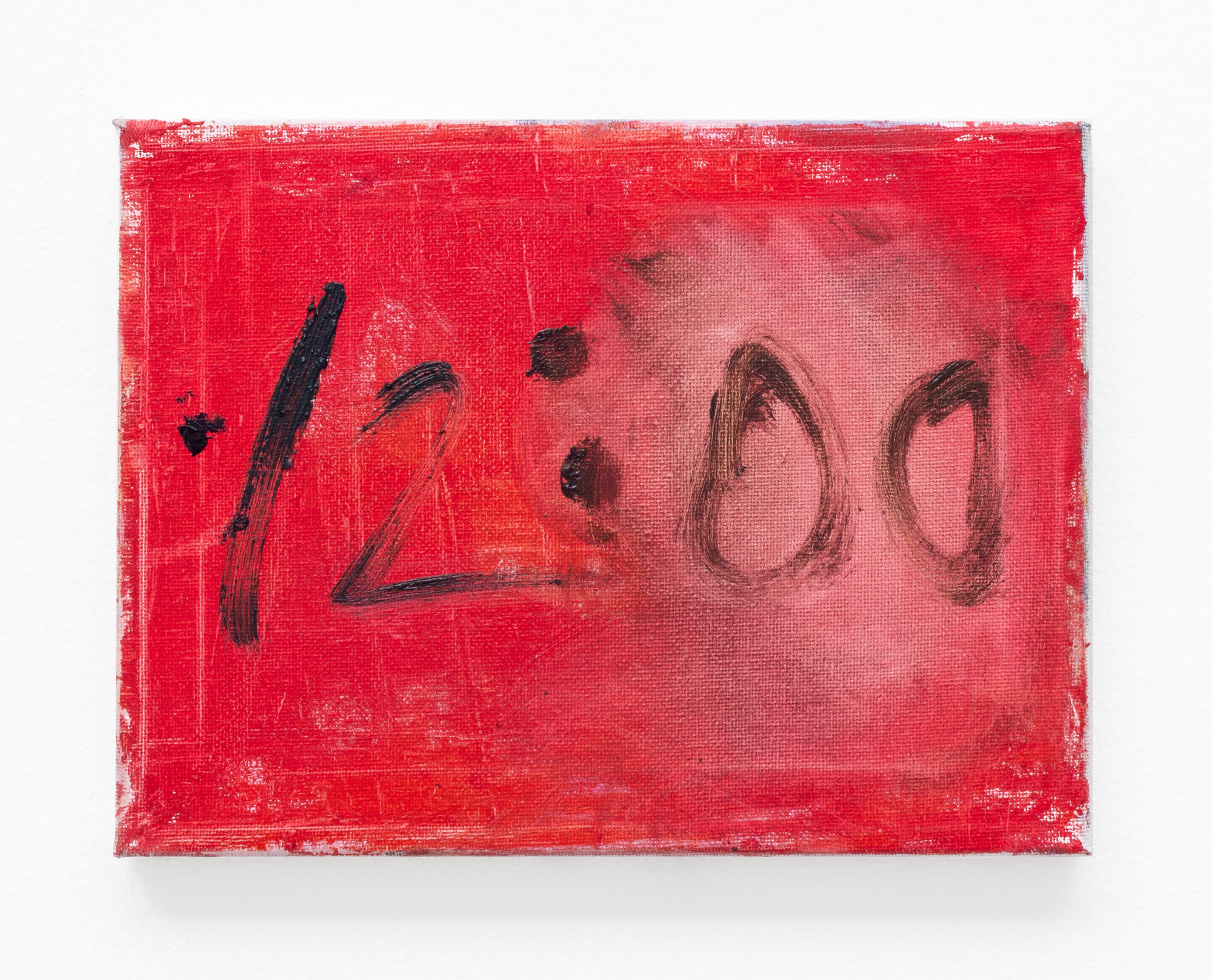

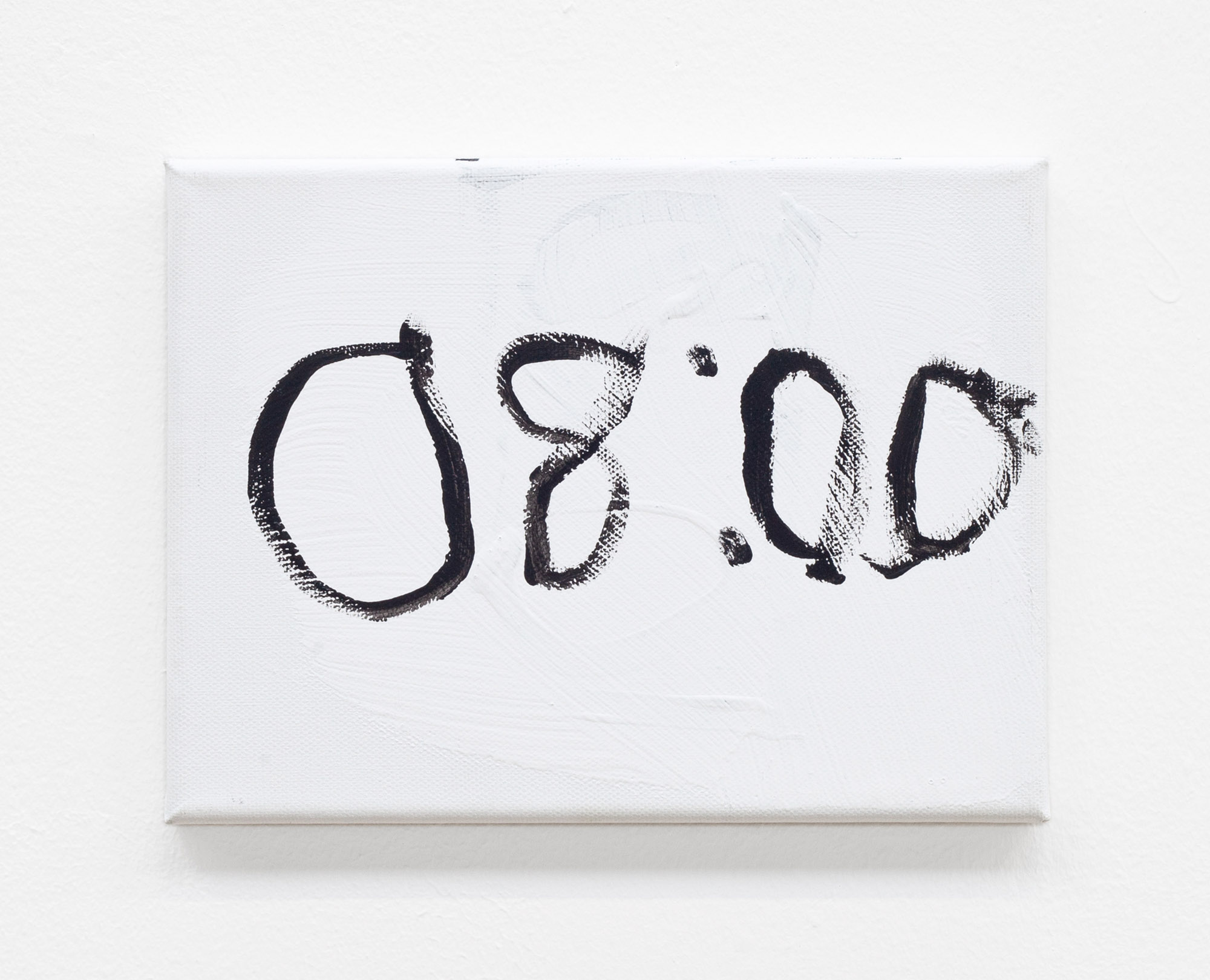

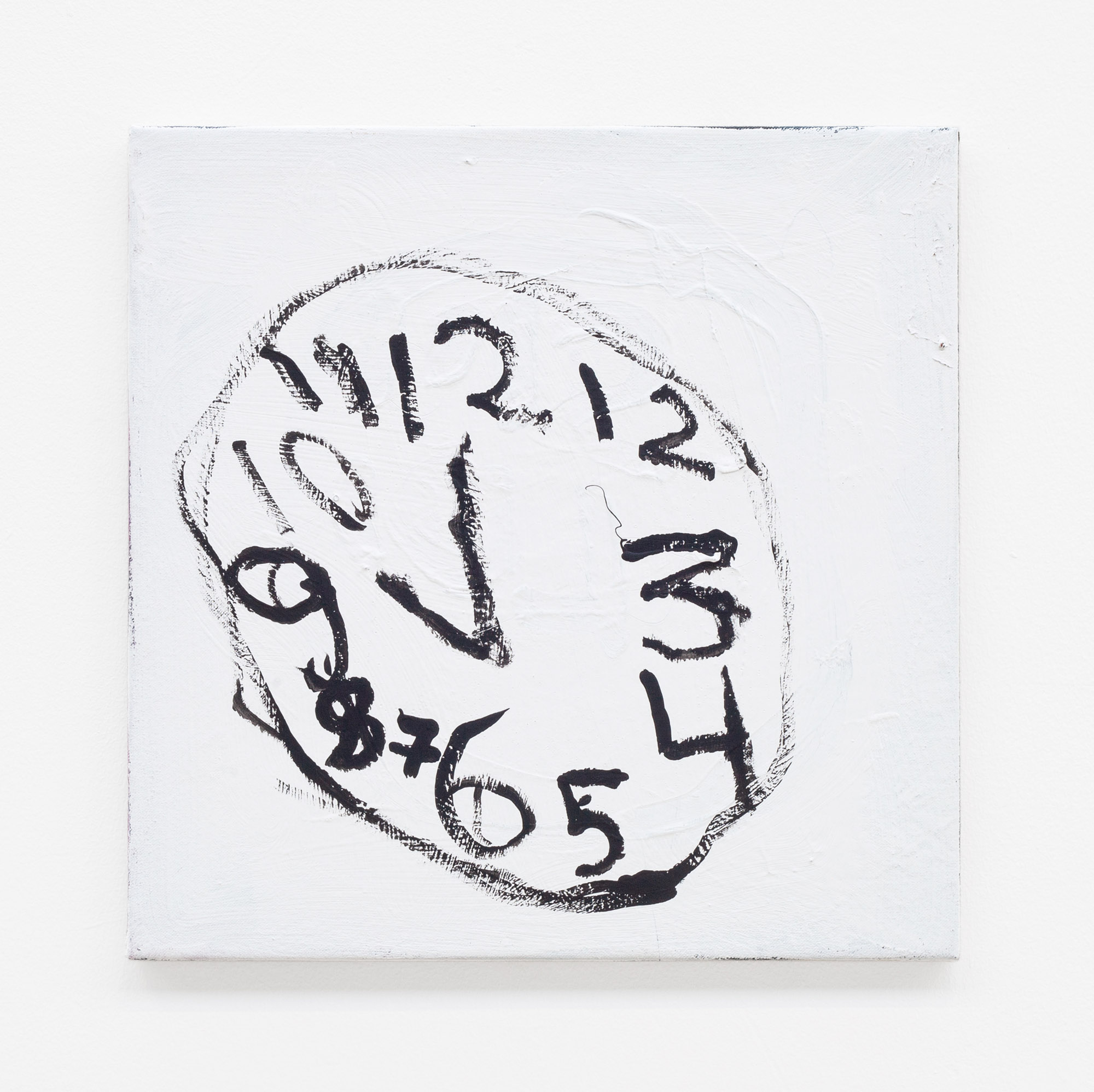

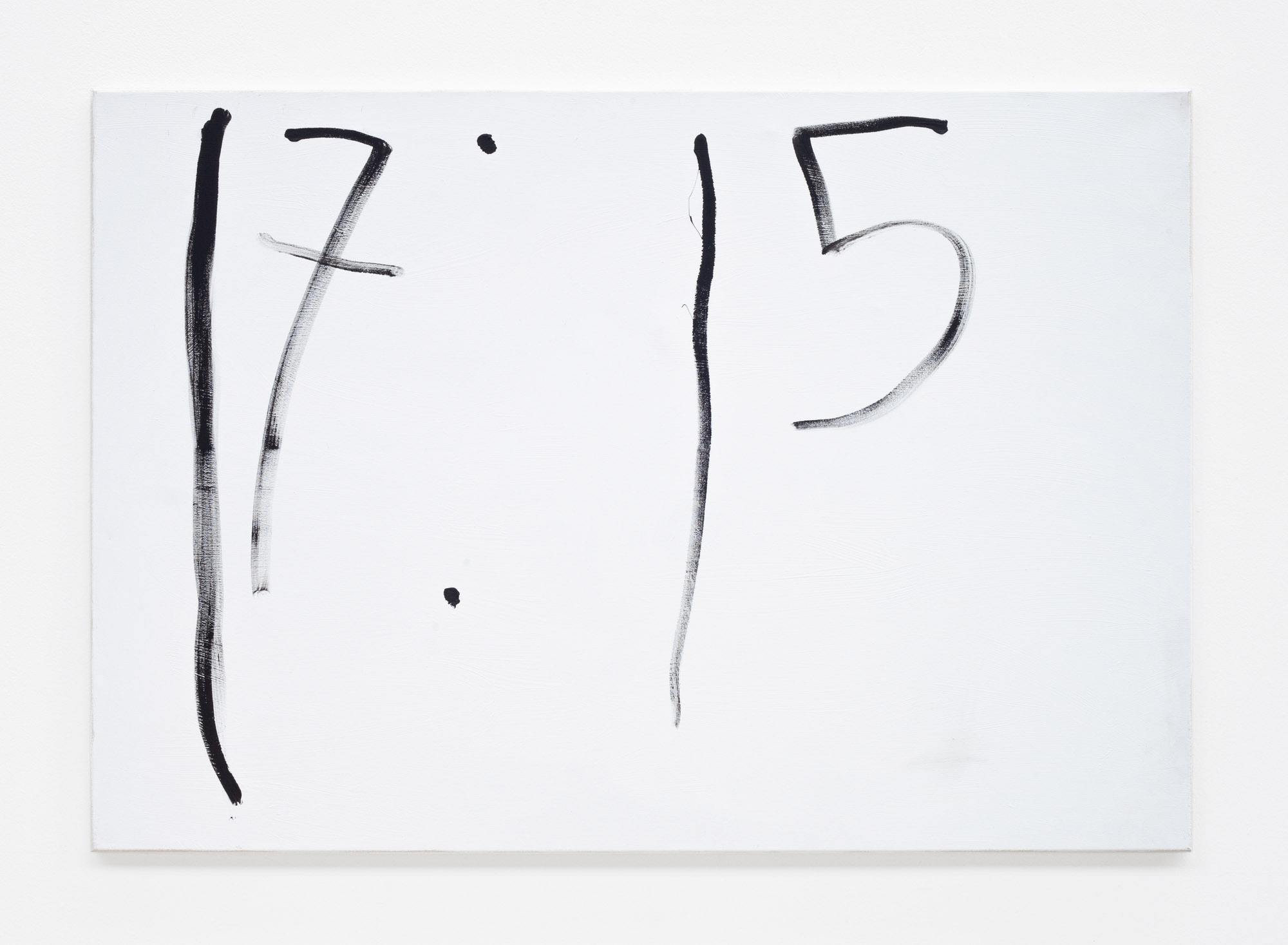

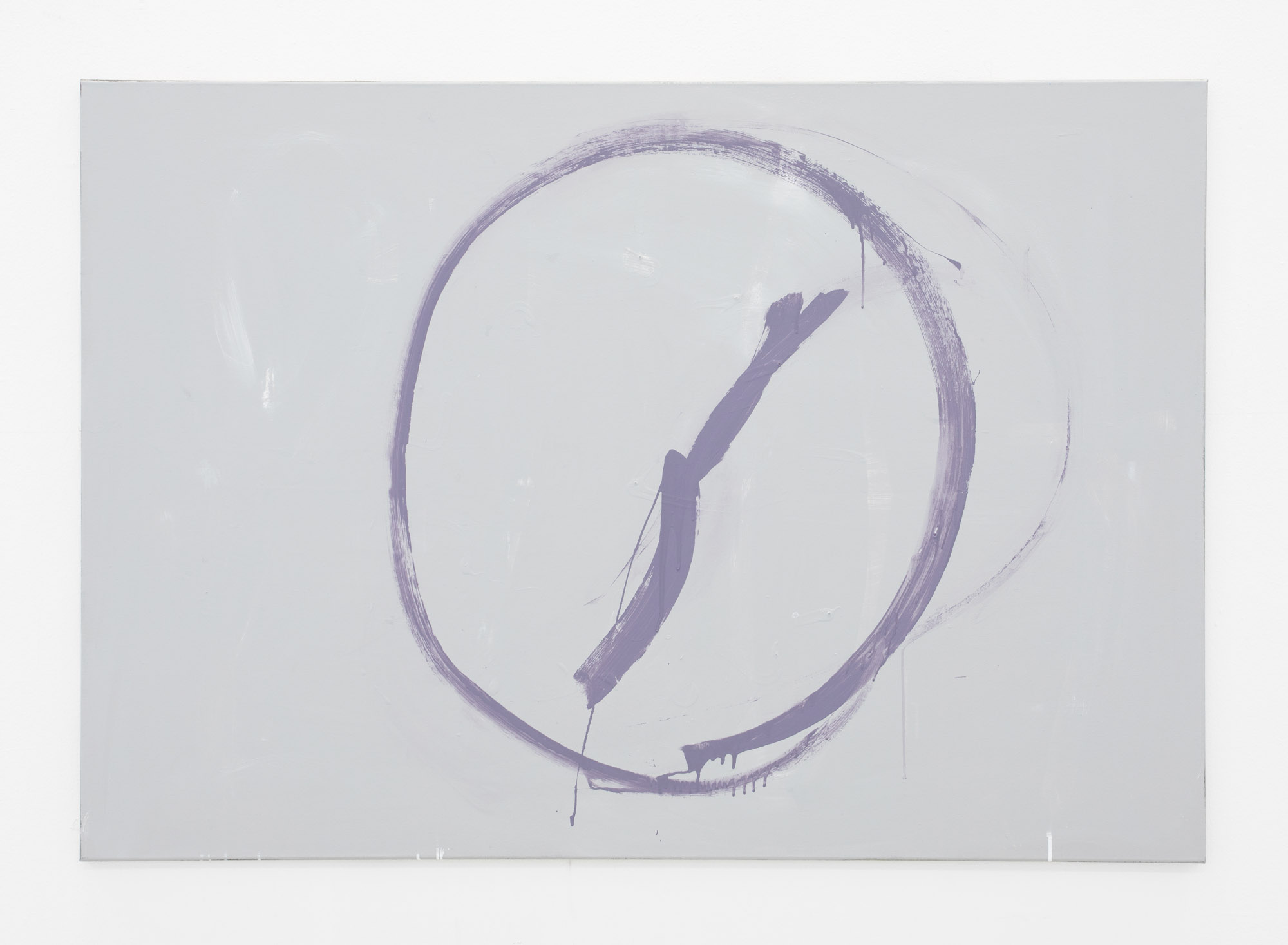

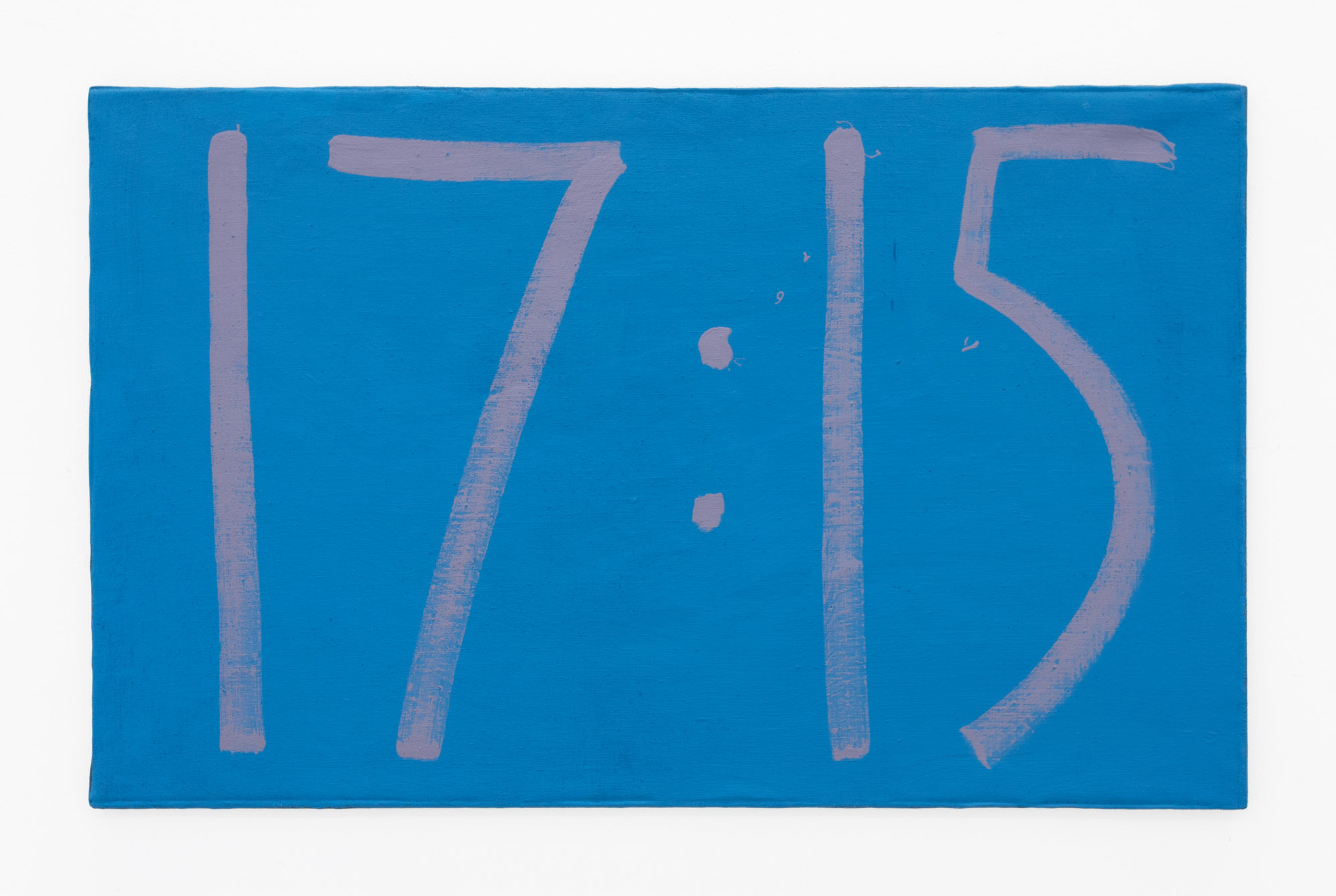

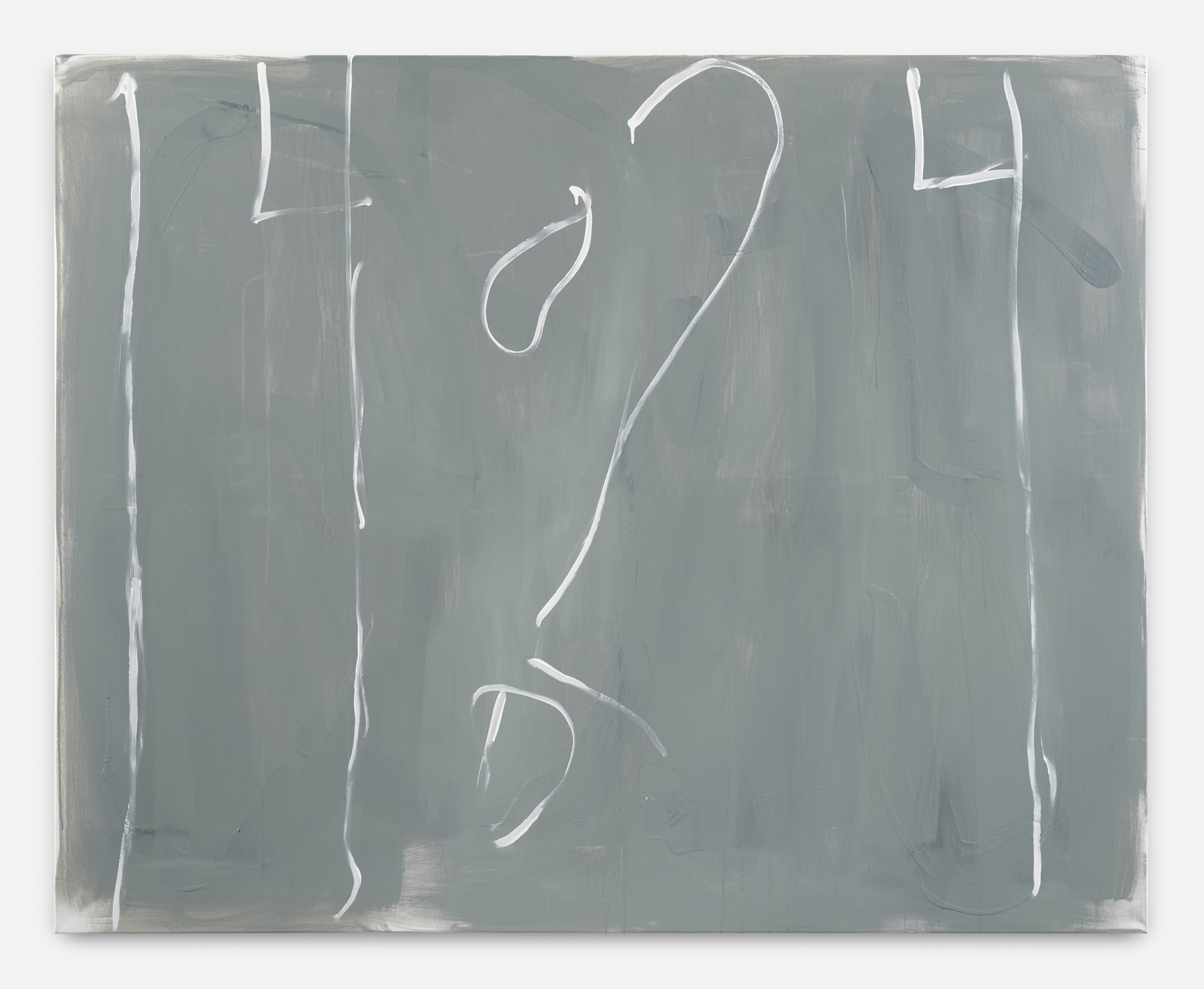

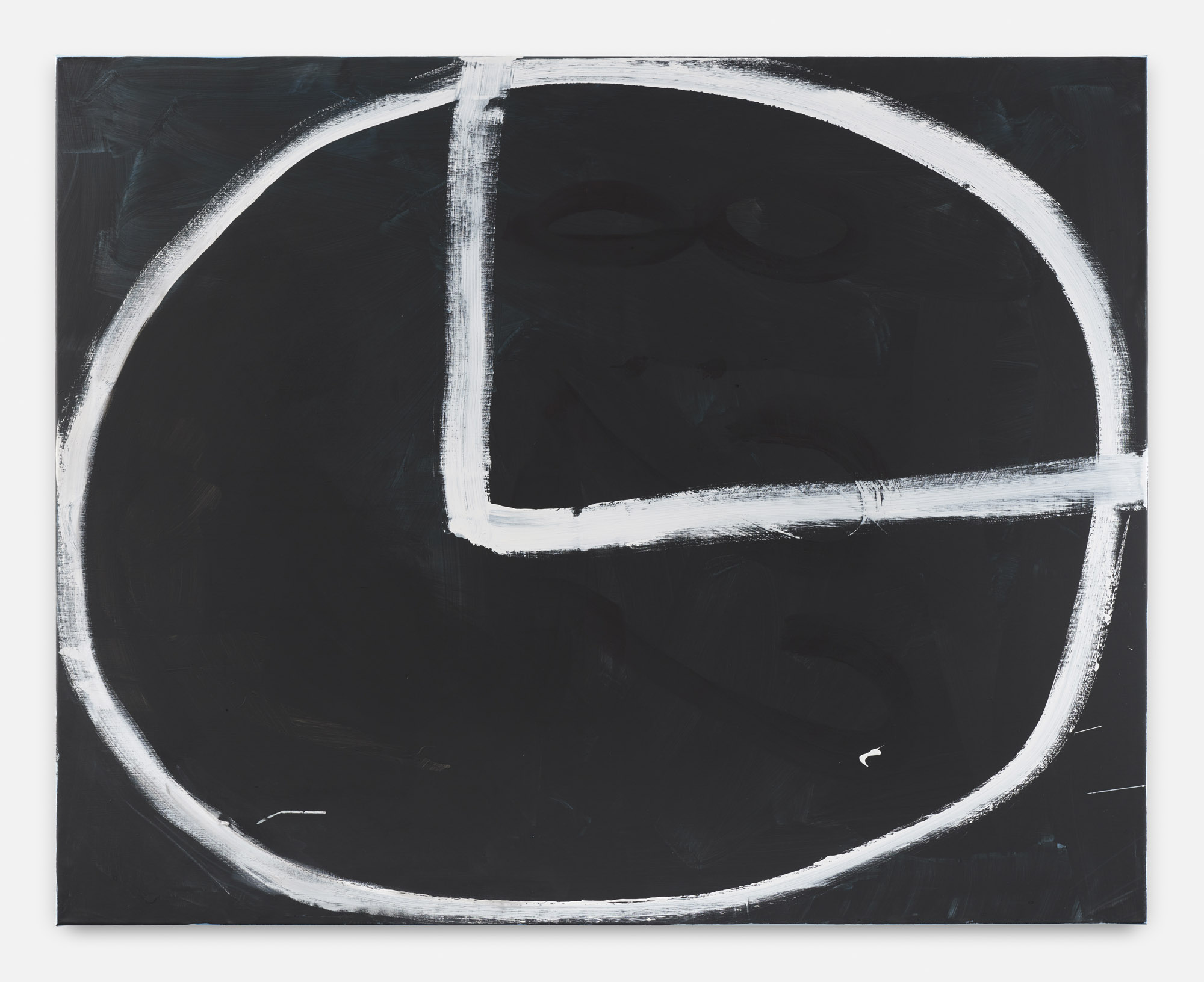

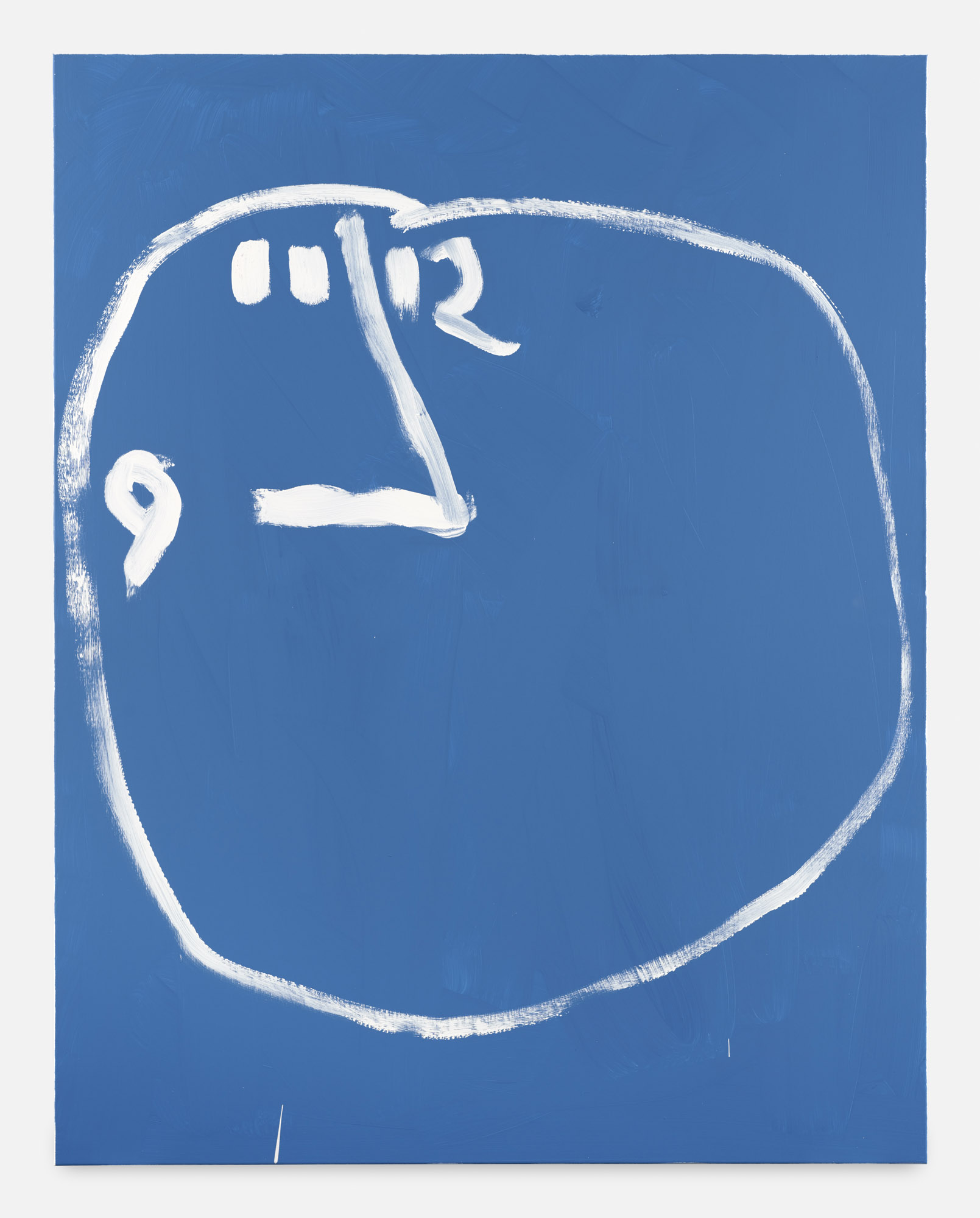

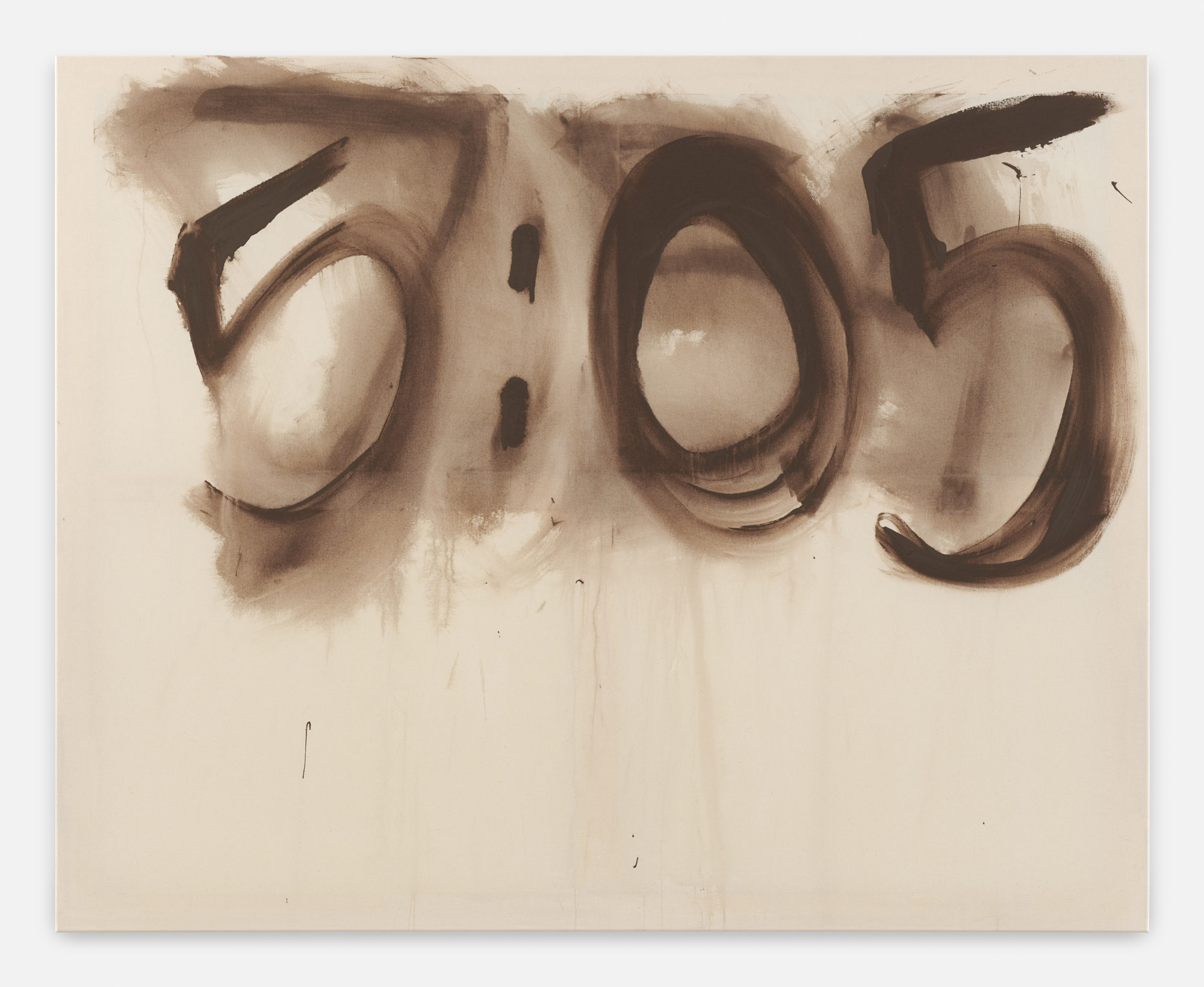

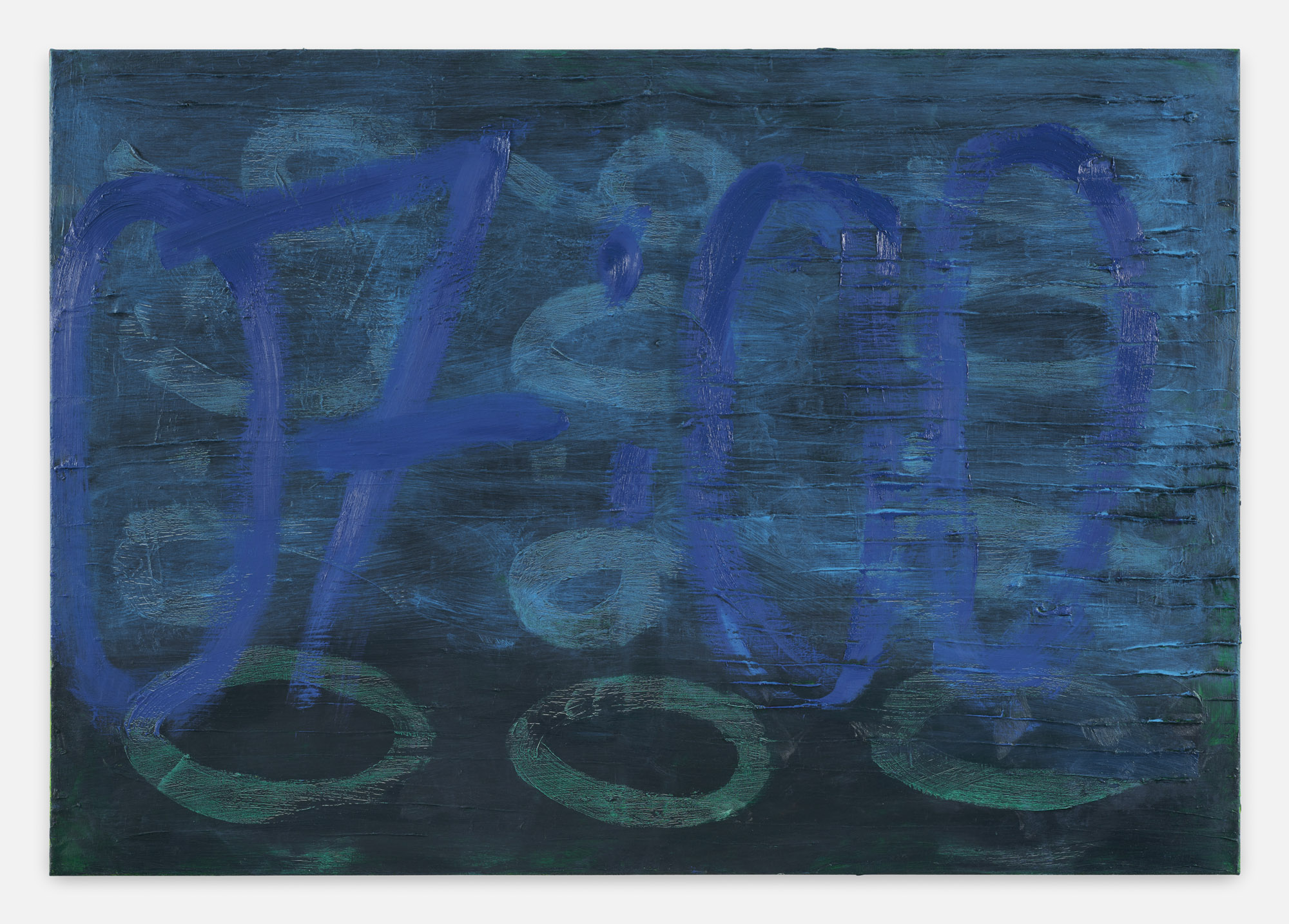

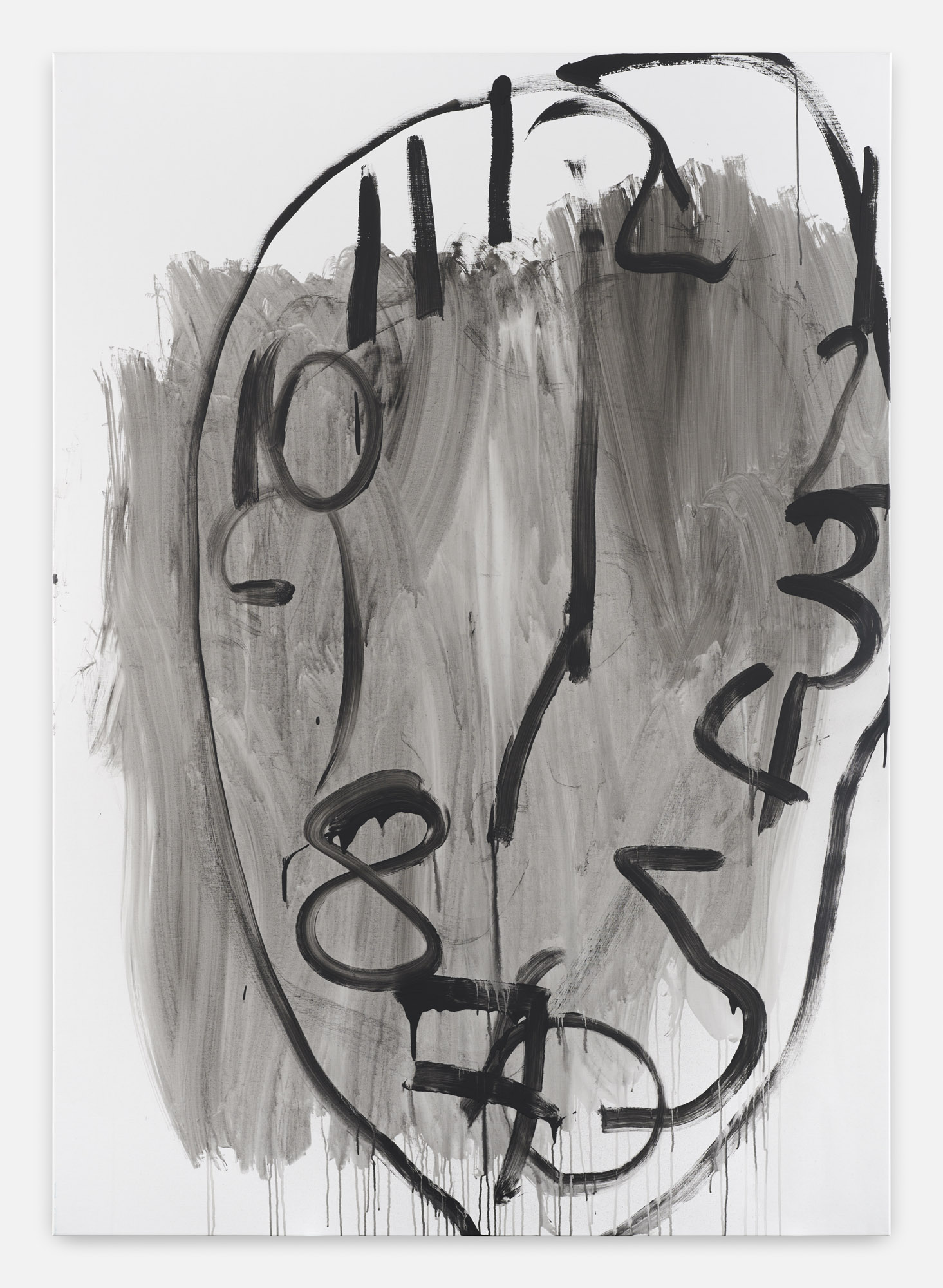

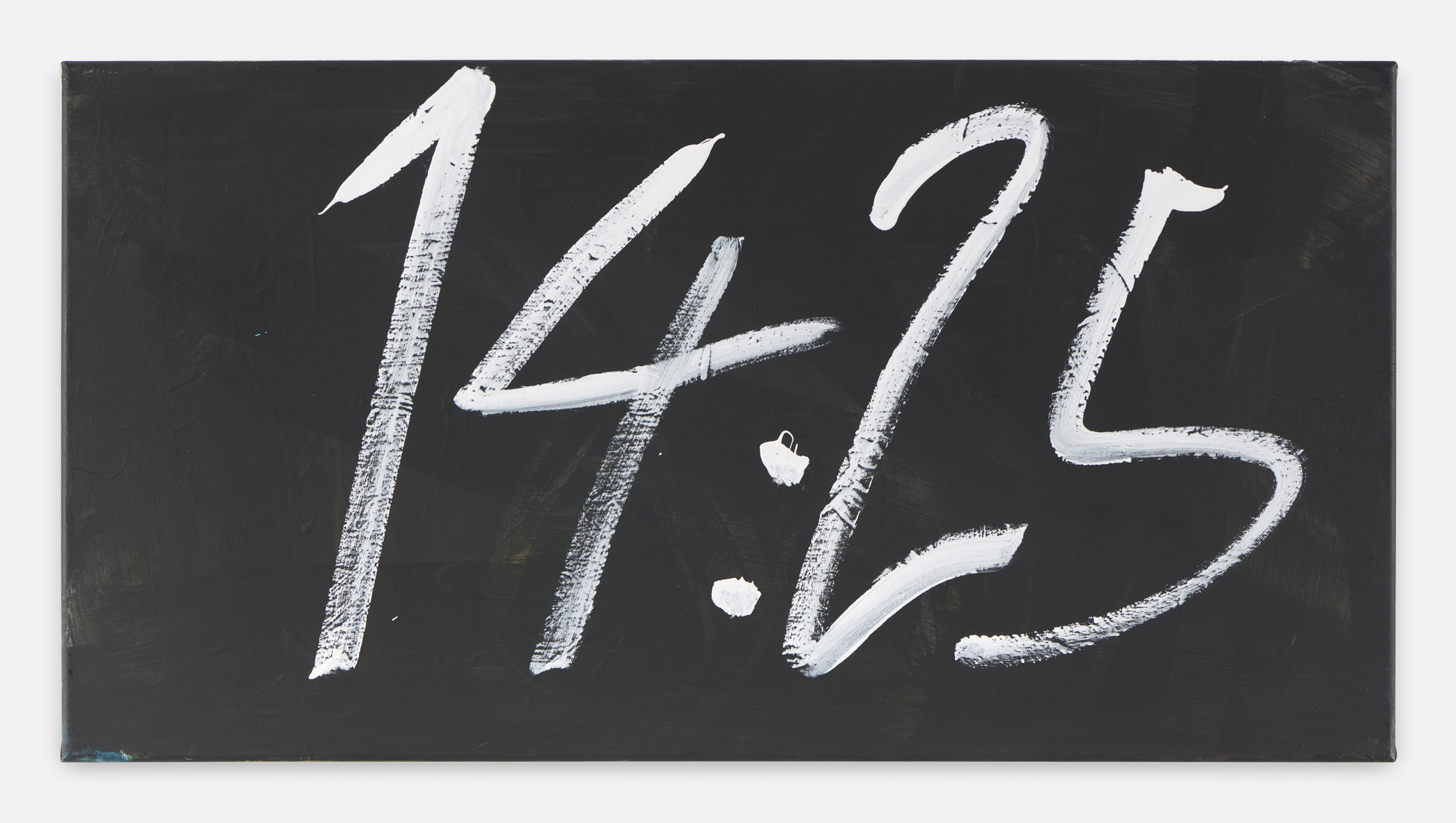

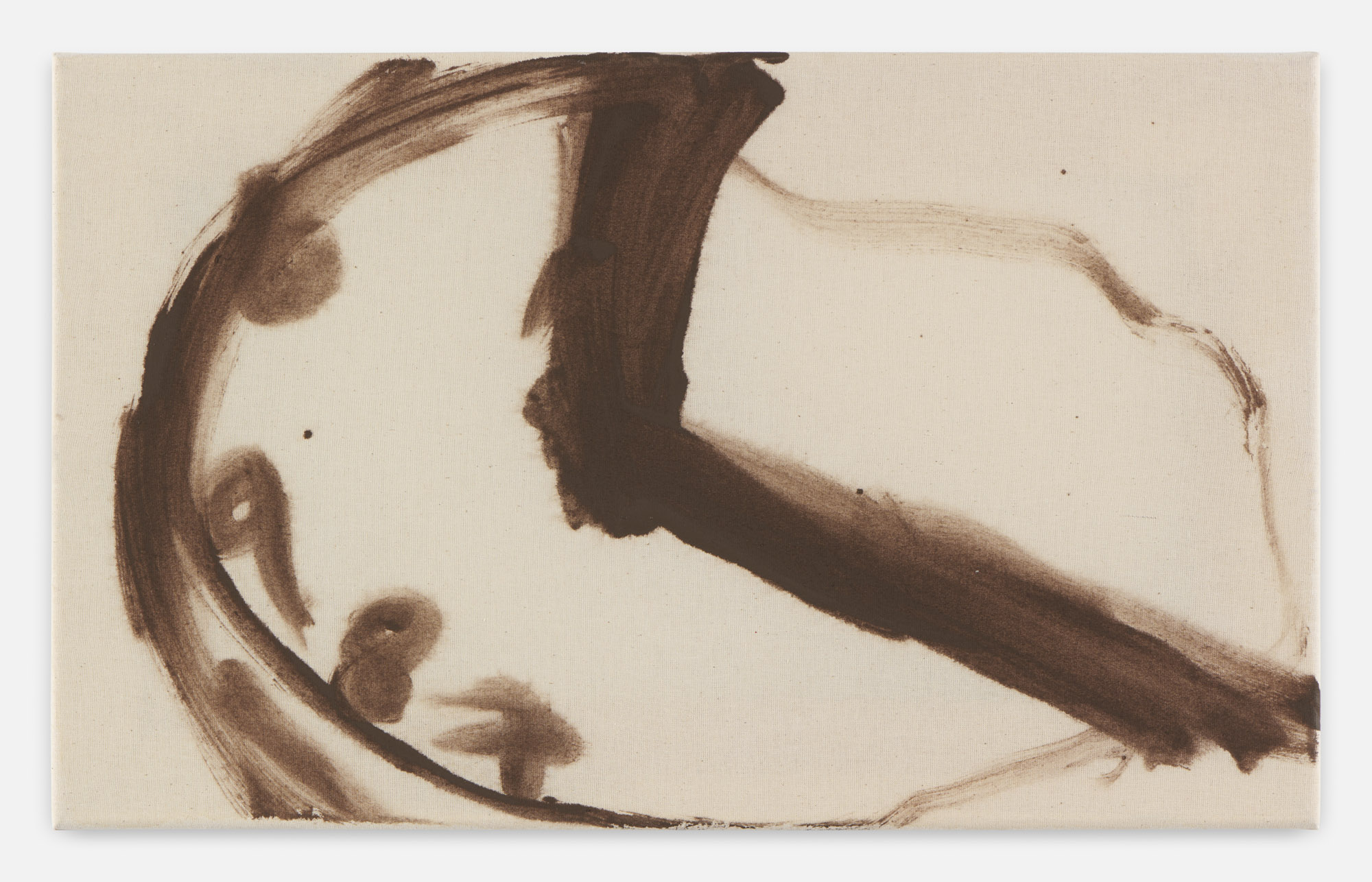

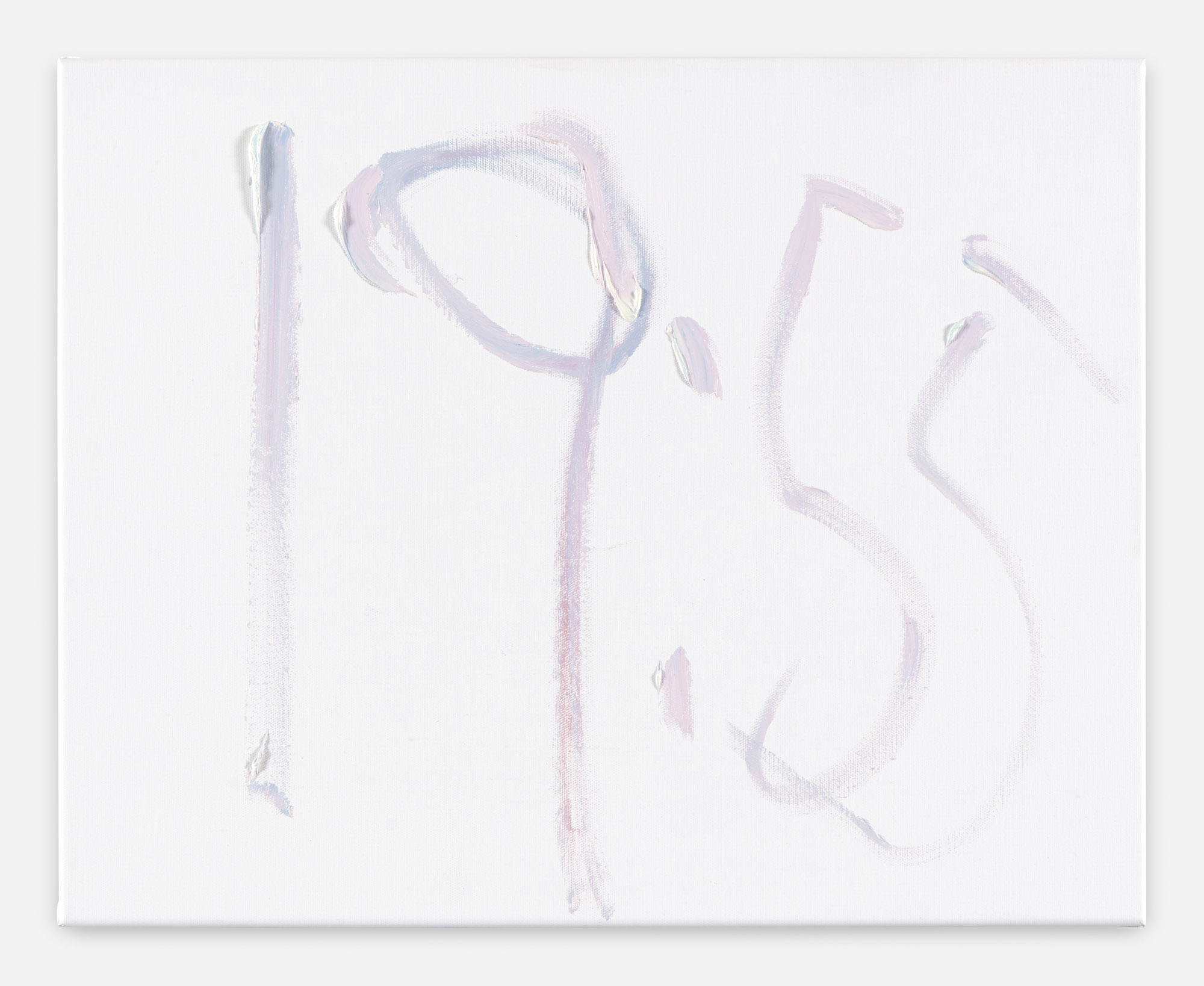

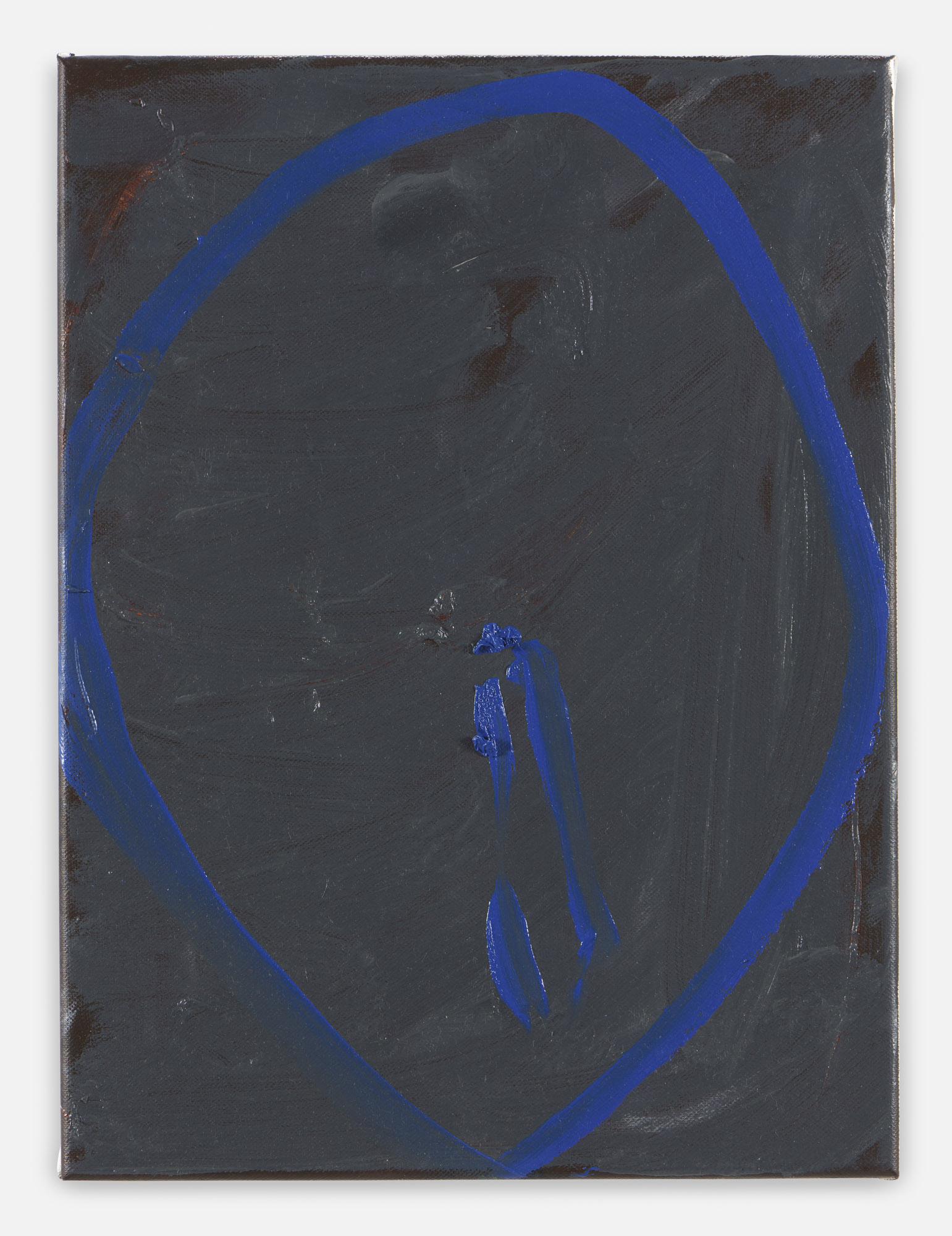

All works feature times of day, both in analog and digital form, as display and as dial. However, they were not painted by Clausen himself, but by assistants. Still, they look as if they were made by a single hand. The conceptual approach of planning and delegating tasks coincides with the freedom of gesture and the aesthetics of imperfection.

At first glance, a few questions arise: What do these motifs mean? 7:34? Viewers and critics may find themselves interpreting them right away: Did anything of historical importance take place at this particular time of day? Could it be a reference to a political or social event? Or does this moment have a more personal, private significance for the artist? None of the above. Whether it is 7:33 or 7:35 makes no difference, these times recur the next day just the same. The time turns out to be inconsequential, it’s part of a game, a mere placeholder, a reason for applying brush strokes. The statement on the canvas is a red herring, the highlighted information is misleading. The paintings, unmistakable with their large numerals and dials, are blurbs of pointlessness. They quite simply show what they are: strokes, lines, circles, dots, composition. It is the differences in these that matter, not those in the clock times that occasionally jump forward or back a few hours. What keeps recurring, however, are the main features: Dials, clock hands, and numerals that indicate the time of day. We are familiar with similar repetitions of motifs such as Claude Monet’s water lilies, Vincent van Gogh’s self-portraits, or Peter Dreher’s water glasses. What they have in common is a painterly exploration of specific experimental criteria; these are tightly defined in terms of motif, but it is precisely through these rules that they allow for a more intimate focus on the act of painting. It is not so much the subject that matters, but the involvement with painting itself. For Clausen, this means: How do compositions ignite dynamics? How do thin lines interact with broad sweeps? How is it that gesture becomes more painterly when skewed? How can the oblique hover? How does the imperfect float?

There are precedents in art history where the artist is not the painter. Many old masters had their assistants and pupils paint for them or take over certain parts of a painting. Today, mega-studios employ diversified workforces who build models, create digital animations, take on architectural planning, handle special materials, and execute entire installations, sculptures, or paintings. In contrast to Clausen, however, these art studio enterprises operate with highly professionalized workforces who reliably expand their portfolio of possibilities. Clausen is not about increasing the level of professionalism or the range of his services. In fact, “Atelier Clausen” would not be a trustworthy company, because, apart from trained painters, he also hires self-taught artists and novices. With all of them he plays his game of clocks. Clausen draws a time or a clock face on a piece of paper and then has the assistants solve the task on canvas, transferring numbers to dials or the other way around. And if an assistant should make a mistake, the art world will never know. After all, 7:35 works just as well.

Multiple authorship is an approach Clausen shares with the graffiti world, where sprayed or painted crew names represent several individuals, not only the writers themselves, but also other members, such as those who stand guard or simply watch. Observing a work in progress plays a more important role in graffiti than in fine art, as friends of the sprayer are often present to watch and provide feedback on the creation of a piece. In other words, the sprayer is accompanied by real-time commentary and will sometimes respond to the remarks, sometimes not. Such conditions mainly arise when there is time to spare and no imminent danger of the police showing up. Paintings, even if they only bear a single signature, are effectively often collaborative projects as well, the work of a crew, a writer and an observer, and the communication between them. The importance of the bystander in painting will be discussed in more detail further below.

Crew names do not necessarily consist of letters, they can also take the form of a character or symbol, similar to the clocks that represent a whole team, an entire joint project. In Clausen’s case, the painter’s name does eventually appear in the works’ titles.

Short, fixed time intervals also give rhythm to graffiti and connect the two painting practices. Especially when it comes to train graffiti, timing is crucial. When, for example, a subway train stops during its journey and an entire carriage is painted, sprayers often only have three or so minutes before the police are called and they have to make a run for it. Tagging on the street, on the other hand, only takes a few seconds, before the next passer-by turns around. Clausen, who has a history with graffiti, also sets a precise time frame for his hired painters, ranging from ten seconds to twenty minutes. This allotted time window, however, leaves room for what Clausen can’t control: One person may deliberate for nineteen minutes and only paint for one, while another may paint non-stop for twenty minutes. Everything revolves around experimentation, play, teamwork, and communication.

His youngest painter is eight years old, his son. Others are between fifteen and forty. Only one of them has completed training in painting at an academy, but the self-taught painters are more intriguing, Clausen explains. One of them had never painted in oil before. After she tried her hand at a small format, Clausen immediately went ahead and got her a hundred small canvases and let her go to work. In his team, free spaces, still unformed hands, and authentically askew gestures seem to be what it’s all about.

However, the aesthetic imagery is not left to chance. For one, Clausen picks the painters himself, of course, and as the results tell, they share a similar style. The format of the canvas, the colors and brushes are also up to him. And finally, there is the conceptual simplicity that limits the palette largely to the background color and the color of the stroke. Perfection is deliberately factored out; instead of tidy and accurate, results are crooked. Often there are a number of layers hidden behind a finished painting, previous paintings, other times of day, which Clausen considered incomplete and had painted over. “Incomplete,” however, does not equate to “bad.” Clausen thinks in other terms, in terms of process, in terms of maturation and further interaction, which a painting sometimes requires. Either the same assistant then paints over, or another one does. He intervenes in this way, much like a music producer at their mixing console. Nevertheless, his painters enjoy more interpretive freedom than musicians in a classical orchestra, Clausen notes. When asked whether he sees himself as a painter or a conceptual artist, he smiles. He used to paint himself, painting remains an exciting subject, but he prefers to look at it – instead of getting involved handling the brush, he takes a step back. This perspective permits him a different mode of reflection. Clausen muses that to achieve the same outside perspective, he might place a painting he made himself facing the wall and then wait for enough distance and blurred memories to creep in after twelve months. The often underestimated role of a third party, that is, besides the artist and the painting, is also highlighted by Belgian painter Walter Swennen. In a conversation with Miguel Wandschneider, he told of a friend who was fortunate to have a good eye. This friend would often visit Swennen’s studio in his absence and place sticky notes on paintings. “Please do not touch” was the message that helped Swennen realize that a painting was finished. After all, that is precisely one of the most difficult tasks in painting: to see, to feel when to stop.

Clausen takes on the task of the friend himself, precisely because he is not currently painting. The observation of paint-ing thus forms a reflexive level in the process from the outset.

Even if the artist’s gestures do not figure here, reflecting on the aesthetics and the composition is indispensable. Style evidently still plays a key role in Clausen’s project Work. The paintings have a lot in common, especially their autodidactic art-brut aesthetics. Sometimes the numerals are too big and end up crowding the canvas, others seem to be laid out too small and appear lost on the wide format. The circles of the clock faces are crooked, the dials distorted in a childlike way. The paint itself appears damp, even watery. The marks, color and lines are leaking. The image resembles the surface of a pond, where rings from a thrown stone or ripples from swimming ducks fade after a few seconds. The pond below contributes to the movement of water, but the visibility of what lies below is blurred. The clock paintings also contain several layers in depth, overpainted clocks. While the surface remains in motion, the paint floating, the view down is possible only here and there.

The series of clock paintings will continue, perhaps involving new employees, perhaps relying on old ones. The future painting’s titles will tell. Whether non-painting painter Magnus Frederik Clausen himself will take up the brush again remains to be seen.

(translation by Lian Rangkuty)