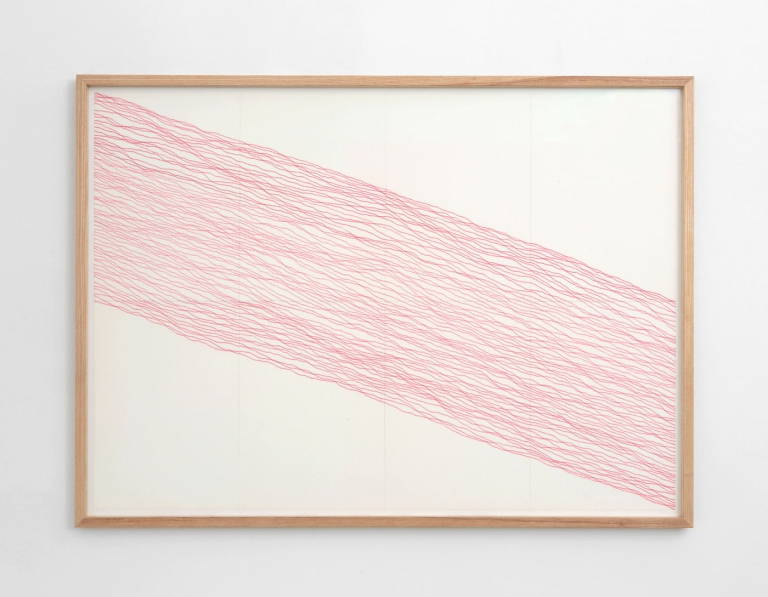

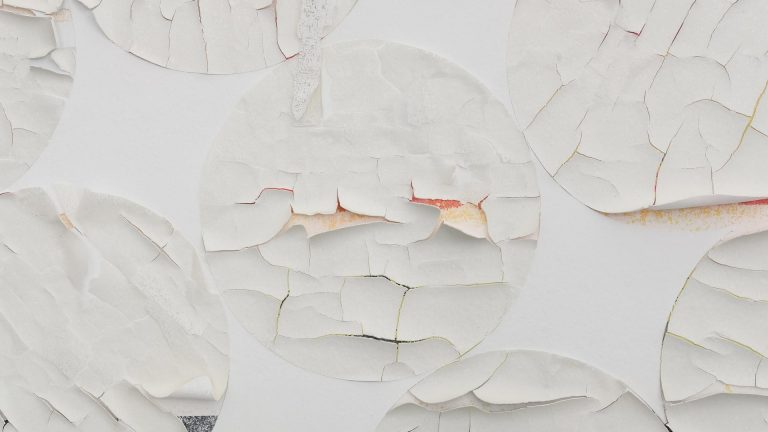

Artists: Lutz Braun, Clémence de la Tour du Pin

Exhibition title: Emotionalmuseum

Venue: nationalmuseum, Berlin, Germany

Date: April 6 – May 1, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and nationalmuseum, Berlin

When Raaf van der Sman asked me to show at „nationalmuseum“, I was happy to be invited because, after having been involved in a number of group shows all orchestrated by Raaf, I had been hoping for it. On the other hand, I knew that showing at an institution with that name would involve steering towards some potential for a conflict on the grounds of integrity. If I remember correctly, it had already been a joke between us that this kind of a project needed to be mockingly named a paraphrase of the place’s name, which was „Emotionalmuseum“, right away.

The work of Clémence de La Tour du Pin had appealed to me for some years, mainly because I had sensed in it a craving for aesthetic experience which had been overridden and thereby decayed through modern social arrangements and the omnipresent lack of sensuality that lies within the nature of a thing called digitization. The traditionally so very German abstract, idealistic and mainly destructive approach towards humanism in addition to a widespread unwillingness to confront oneself with social, economical and political developments in the past century, and not digitization, have prematurely surrendered me into the company of ghosts, nightmares and long gone dreams of a cosmopolitan society. Especially the German bourgeoisie has utterly unmasked any positive reference towards the idea of the nation.

The title „Emotionalmuseum“ you suggested appealed to me because I had been working with this abandoned 18th Century French hotel Particulier since quite a while. It made me laugh to imagine this vulnerable space as a museum – ruined, destroyed and hollowed. I also kept in mind our conversation the other day on the phone about voyeurism. The movies ‘Grey Gardens‘ and ‘Ein Haus für Punks’ explore themes of destruction and marginality and feature people in their own lives. At which point are they exploited by the filmmaker? When – as an artist – are you becoming voyeuristic on your own milieu? I always felt weird about going into this French hotel Particulier and bringing back objects; I experienced it as being in some way profane. As a child, I remember having lunch in one of the two rooms we were allowed in. I hated everything about it, it was always so cold and boring. The floor and wall were made of dark stones and all surfaces were dirty and dusty. The food we had was most of the time outdated and my aunts would talk about war, dead people and the church. When they would leave the room for a moment, I would open the drawer that was under the waxed tablecloth and spit in there the piece of meat.

‘His face petrifies me, it changes every time he smiles. When the features contract to smile, his skin widens with foul wrinkles. As soon as he stops this happy expression, he becomes less frightful and neutral. In fact, he’s lying when he smiles, he seems to be in a form of dislike of himself, it’s as if his body could no longer hide his inner state of falsity.’ This is an extract from one of the dreams I sent you previously. I thought about it in relation to the last sentence you wrote about the failure of the German bourgeoisie and their attempt to establish a positive reference to the idea of the nation. To some degree I can equate the face in the dream with „the Nation“.

A friend sent me this video a few years ago (URL of Youtube video of Bernard Stiegler on Jacques Derrida) when I was interested in seeing images as ghosts. The video is a bit complicated and messy, but I liked when he says ‘the future belongs to ghosts‘ because it demonstrates an interesting inversion between future and past. Perhaps you also already know about Derrida’s notion of Hauntology? He also explains that we are in a system of machines of desires that are going to destroy themselves.

Derrida’s hauntology was new to me; I am happy I learned about it and shall take a closer look. I used to think that my affinity for deterioration, decay and physical decomposition had a very personal, so-called pathological background to it. When perceived by others, I felt somewhat ashamed and disgusting, maybe even like a necrophile. A Freudian explanation that gave me some resilience was that of a rotting adolescence, a denial to mature, not mentally or physically, but sexually. Anyhow, I had never paid much attention to gender identity.

A four-year-old boy once pointed at a picture of shipwrecked mariners on a magazine cover and told me I had once been such a guy. When I asked him what had then become of me he said that I had drowned. What Stiegler doesn’t seem to mention is that Karl Marx had ( before Freud ! ) already described the projection of (libido is Freud’s term) into products of commodity, that way turning them into a fetish: Warenfetischismus. My rendering of Marx may be a bit negligent.

This is getting weird. The painting “Danse” which I picked for our show originally refers to a French movie which I saw as a child and of which I could never find out the title again. It’s about a group of children who get left by their parents in a big house by the ocean. They decide to play that they are aristocratic grown-ups, and they wear suits and gowns, and they drink wine and hold a banquet. For the dinner, they bake a dead swan they found washed ashore, and they all get sick from it. I don’t remember what happens later, but it’s really amazing how the decadence of imperial France finds its way into the stomachs of children, and gets puked out and that way rejected. I had not been conscious of this background story anymore, but what You told reminded me of it.

-Lutz Braun and Clémence de La Tour du Pin