Artist: Lukas Luzius Leichtle

Exhibition title: All Thoughts No Prayers

Venue: NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, Aachen, Germany

Date: September 9 – October 8, 2023

Photography: Simon Vogel / all images are copyrighted. Courtesy of the artist and NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein

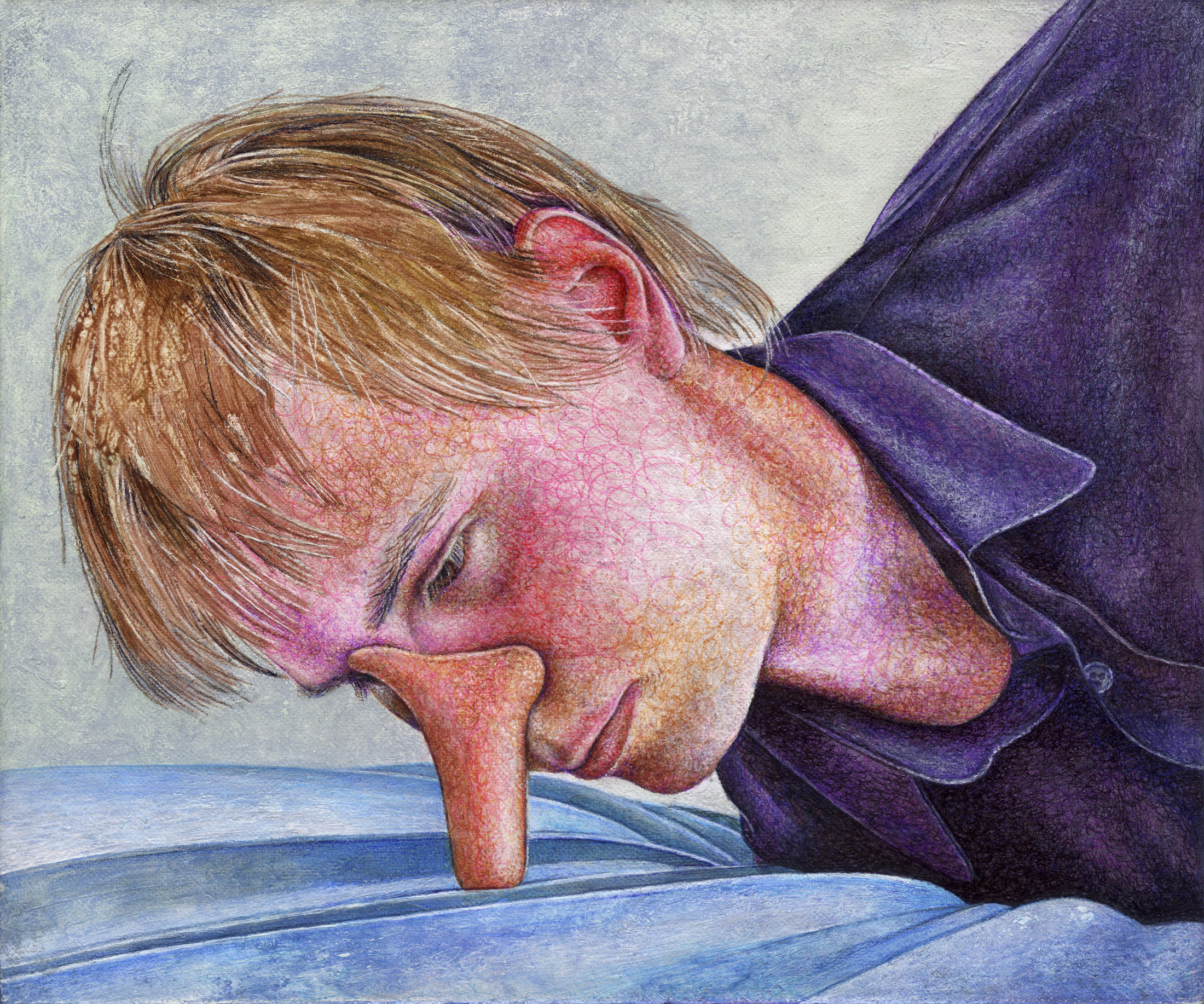

Lukas Luzius Leichtle‘s first institutional solo exhibition All Thoughts No Prayers at NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein presents new paintings and drawings created especially for the Kunstverein. Thematically, the oil paintings build on illustrations from Leichtle’s own experience: he attentively documents himself and selected arranged objects photographically as the basis for the paintings. In this way, he redefines hyperrealism: as something real in which there is dreamlike. Fake in the best sense of the word, but also more real than real.

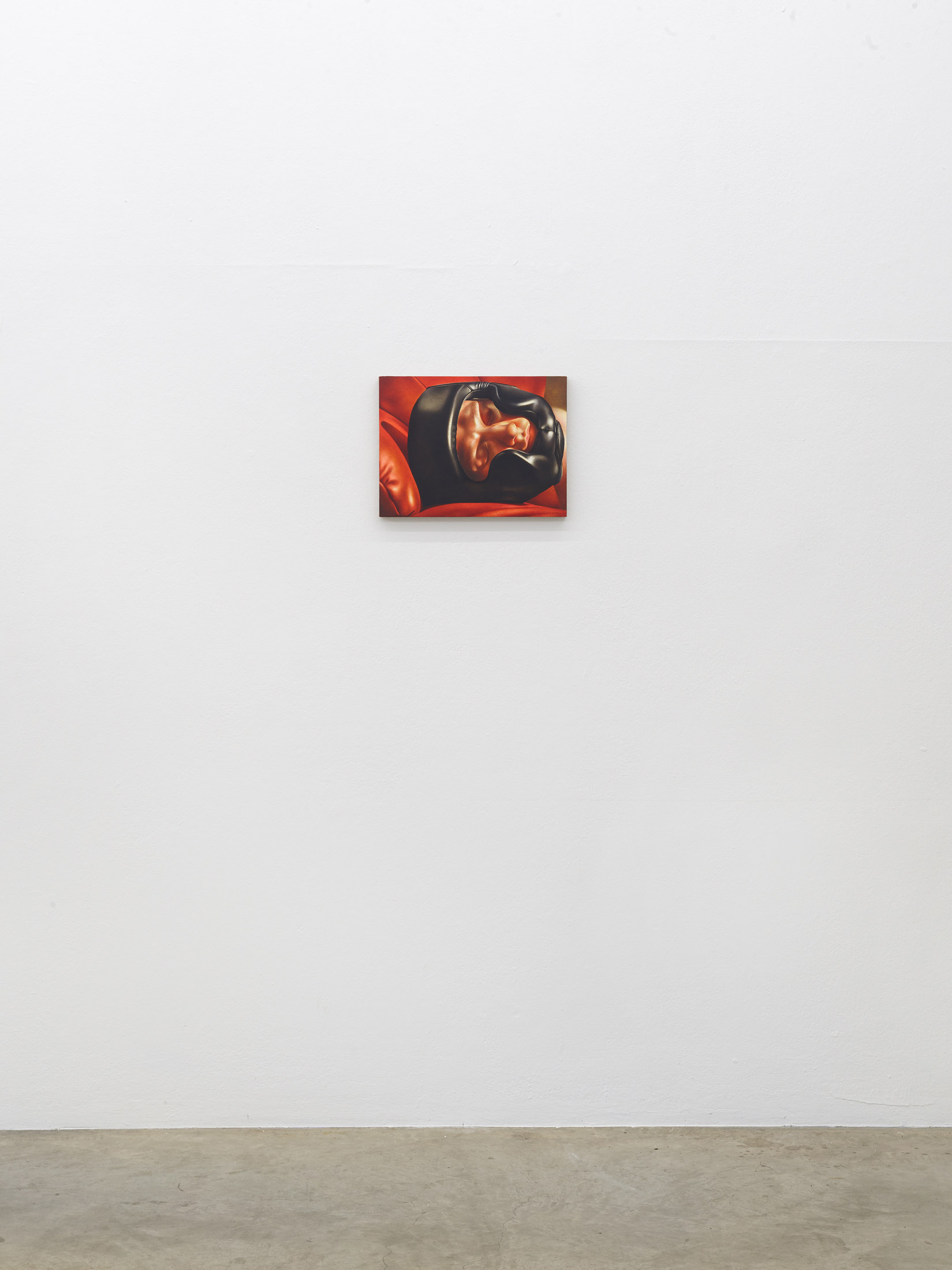

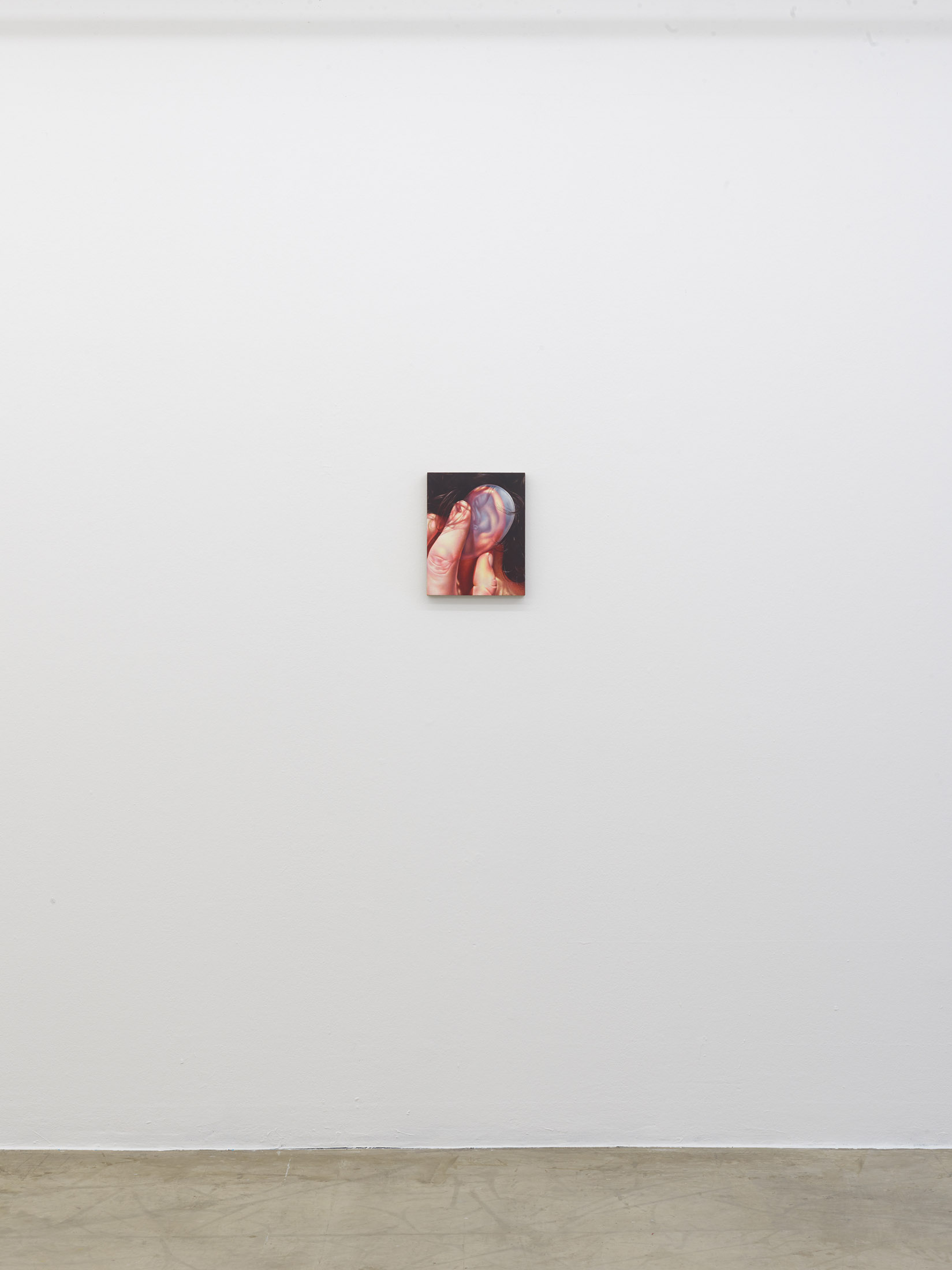

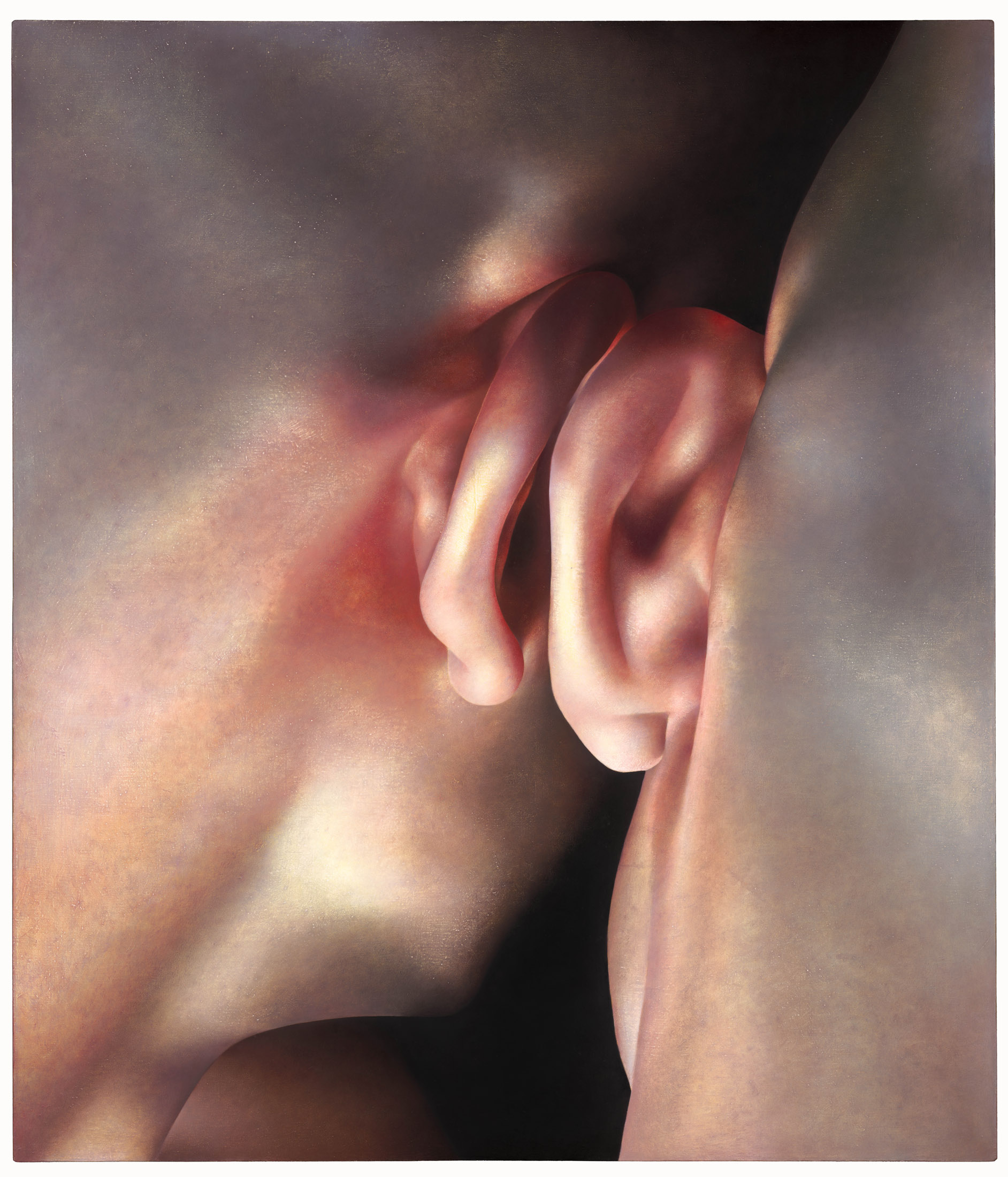

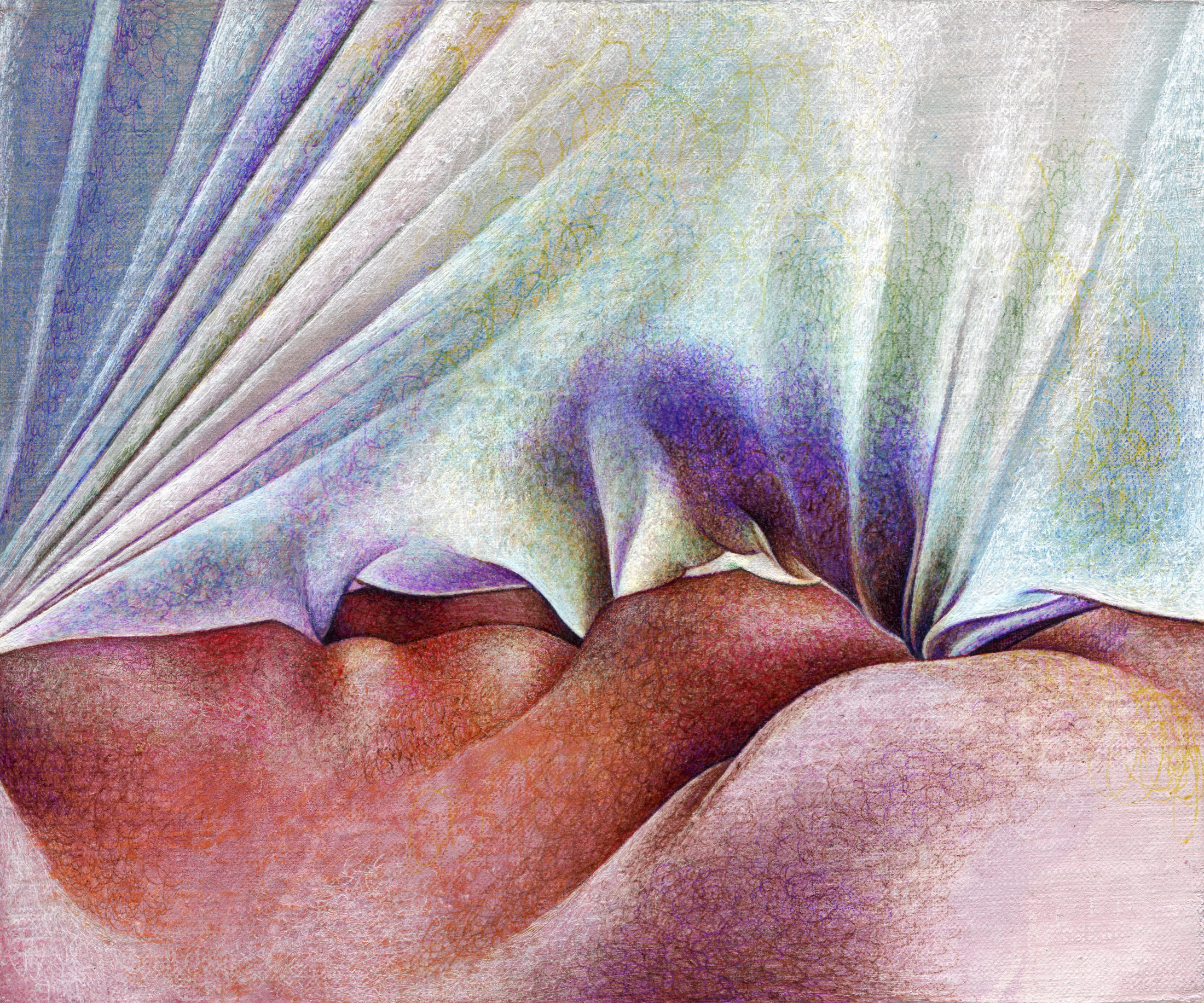

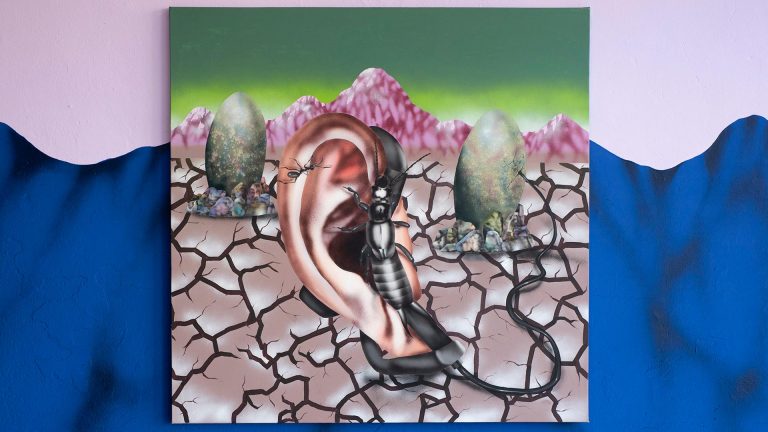

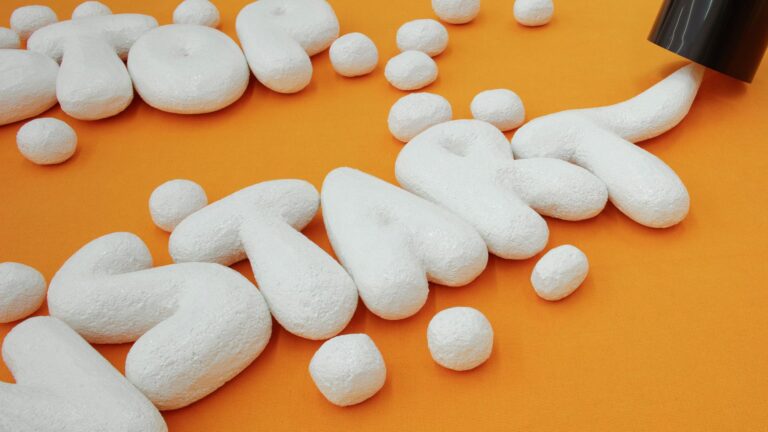

The masculine-looking shaved heads portrayed from behind in Conductor, for example, suggest a casual observation of two people, but are given a dreamlike quality by the picture’s framing and coloring. Leichtle describes the unifying feeling of the works shown as a “vacuum.” A material condition that can be felt as a sensation in the body and is made visible here through images of the body. With this motif, he inserts his subjectivity into the objective situation shots, which carefully take on all-too-real objects from everyday life. Through illustrations and formal language, the images tell phenomenologically of the relationship of experience to the outside world, liberating original states such as distant childhood memories or experiences from speechlessness. The surfaces, partly fabrics, partly skin, acquire spatiality and texture through highlights and depths that the painter applies in countless layers. A deepening of the surfaces, or what Leichtle describes as a “haptic noise,” which becomes a precise visual and emotional experience of skin with the application of scalpels, electric nail files, and makeup brushes. The only image of an actual object shows a tipped-out glass. It is only upon closer inspection of the work Hope and Hype that the guided nature of the working process becomes apparent, as it is illustrated in an almost comic-like manner, in contrast to the realistically expressed details of the other works in the exhibition. The dead fly on the pool of water serves as a reference to the art historical debate about the realistic depiction of dead flies, the musca depicta, in Trompe-l’œils, which comments exaggeratedly on questions of figuration in painting. In keeping with Leichtle’s claim to realism, there is a cinematic look in his paintings that is at the same time reminiscent of theater tableaux: lively but arranged, camp but melancholy. Some of the chosen image details seem defiant, like looking at one’s own feet or an ear bent by pressure from another, amorphous body part. This “unmanned gaze” has seemingly taken on a life of its own in defiance of social limitations, dissecting and thus questioning the socially accepted gaze. Against the unleashing of such a gaze, the coloring, the surface, the recording of the body in Das Rauschen/The murmur conveys support and warmth: embryonic vibes.

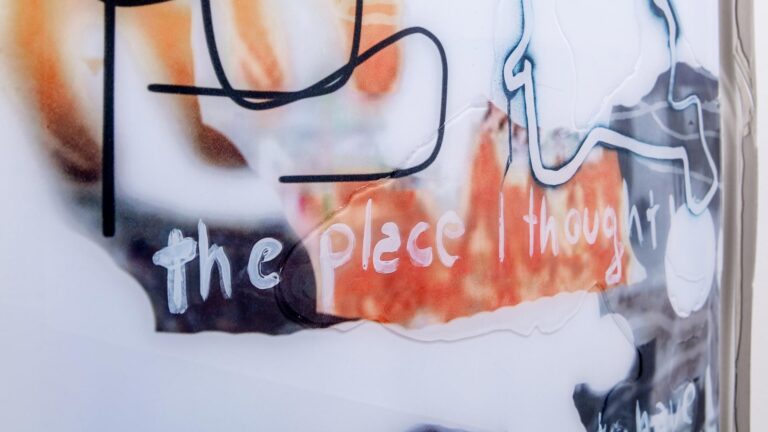

“A weight of meaninglessness, about which there is nothing insignificant, and which crushes me. On the edge of nonexistence and hallucination, of a reality that, if I acknowledge it, annihilates me. There, abject and abjection are my safeguards.“* Julia Kristeva’s abject is a thing between object and subject that evokes disgust. To repel it is to protect two separate realms, to simplify reality, as by distinguishing purity from filth, heaven from hell. These questions of how distinctions often fundamental to human experience(s) are approached by Leichtle’s paintings through delicacy. They show that horror need not be a reaction to a lack of dichotomy, as the concept of abjection suggests. Instead of violence and defense, the reaction to in-between states and sensibility is interest and attention, which make states complex to experience. It is perhaps more a matter of what happens when we feel attention: in Lacanian psychonalysis, to which Kristeva’s thinking belongs, reality is never unmediated, but is shaped by symbol formation and ghosts of the past. This is underscored by the autobiographical approach most evident in Blende, a series of ballpoint pen drawings based on childhood photographs. The painter does not universalize his experience (as in abstraction), but shows it explicitly as his own individual narrative that hints at collective feelings. She is at odds or in discomfort with norms and therefore demands an attentive look at the emotions that grow beyond these constructs. To be at odds as not to ward off the uncertain, the (dis)disturbing, the formless, the emotionally overwhelming, thus not to follow a patriarchal-violent logic, but to persist in the happening, in the confusing emotion. To ask what relationship or lack of relationship it points to and to digest it.

Leonie Döpper

* Julia Kristeva, (1982), Approaching Abjection, Powers of Horror, Columbia University Press, NY, pp: 1 – 31, p. 2.

Lukas Luzius Leichtle (*1995, Aachen) studies at the Kunsthochschule Berlin Weißensee in the classes of Friederike Feldmann and Nader Ahriman. He lives and works in Berlin.