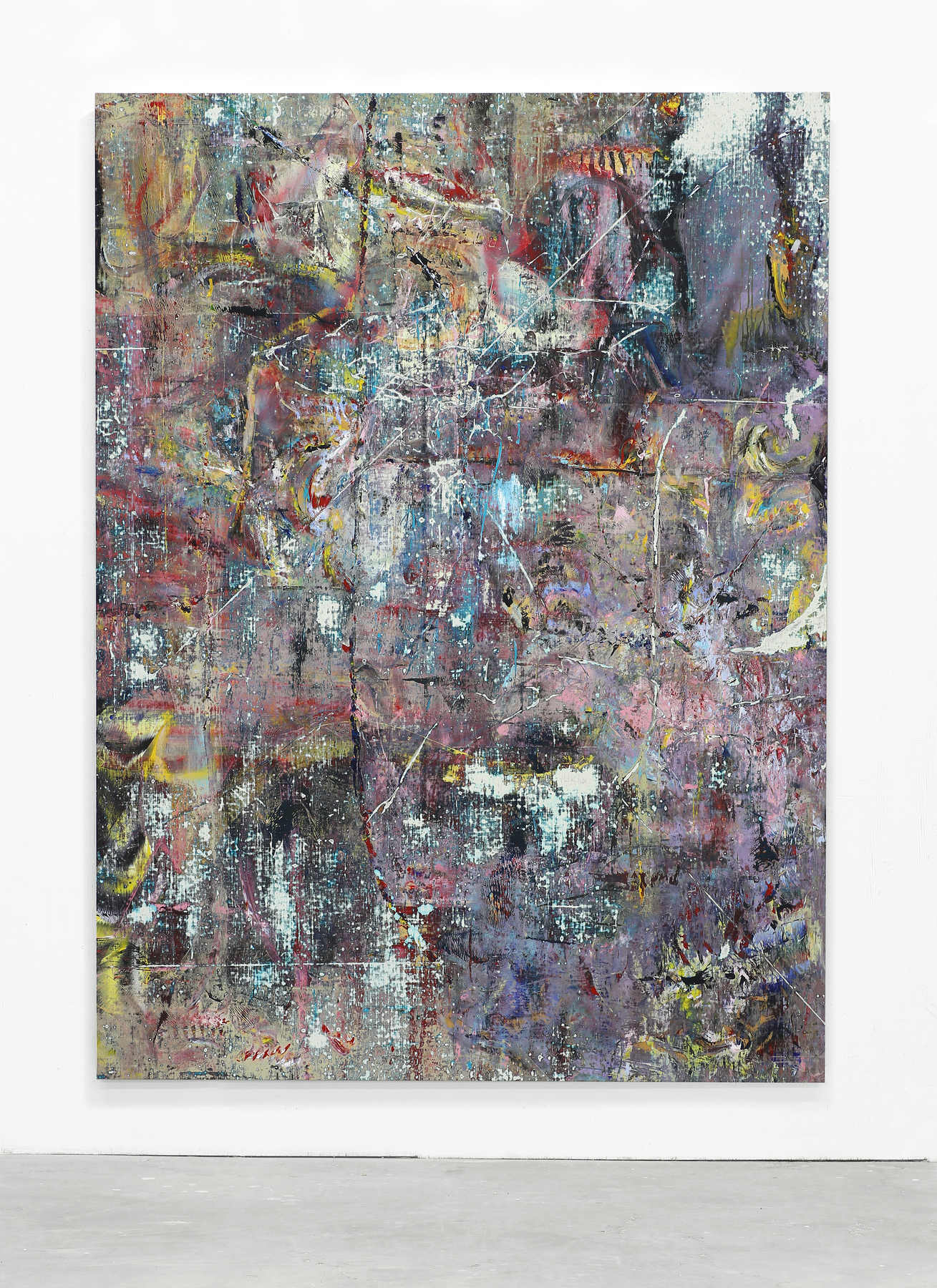

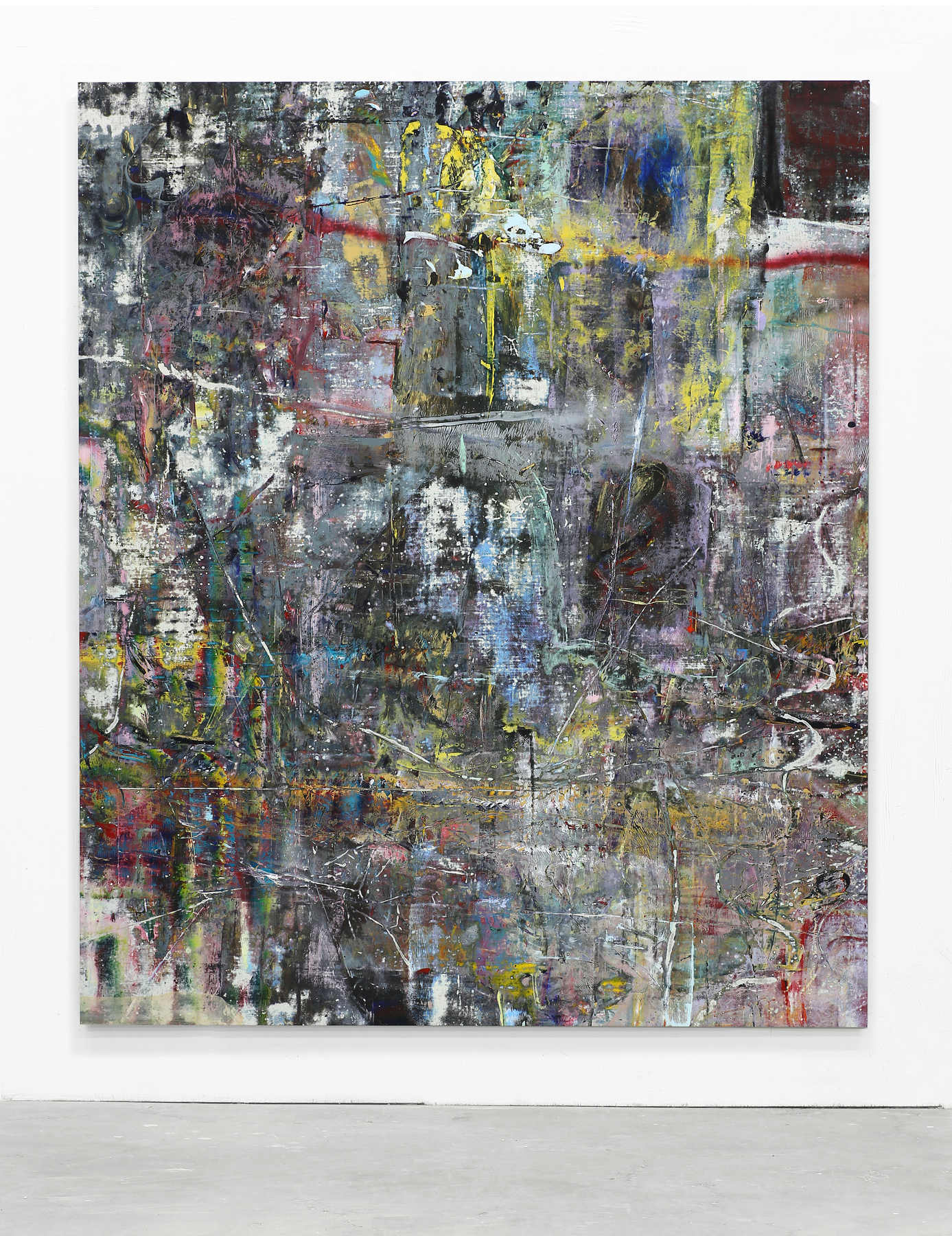

Artist: Liam Everett

Exhibition title: 1970 – 1974

Venue: Office Baroque, Brussels, Belgium

Date: October 30 – December 12, 2015

Photography: Sven Laurent, images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Office Baroque, Brussels

Office Baroque is pleased to present the first solo exhibition by Liam Everett at our downtown gallery space on Bloemenhofplein 5 Place du Jardin aux Fleurs.

1970 – 1974

an alternative introduction could have begun with “the latent presence of violence that remains invisible at nature’s chore….” But that might be overstating the point. So we compromise and simply begin with the more graspable iterative: “something happened.” This ‘something’ is not of the order of fire, earthquake or flood, for it unfolds much more intimately, couched in a body heavy with intent. It rests there beneath the surface—lingering, buzzing, only to appear at random, without order, and always void of meaning. Divination does not call it forth, as much as labor, repetition and blind exertion—and even these are not galvanizing agents as much as ancillary preconditions that outline a space for possibility and perhaps even emergence. Taken a step further and we could claim this forms the basis for a ‘practice,’ but at any rate this is an activity best apprehended in its verb form.

Case in point: The Disappearance of Tal Ben Yaccov, 2010: two performers en route to a performance, carrying only their vital instruments. They circle their objective, approaching the venue, wandering back corridors but never managing to hit their mark. Dress rehearsal or opening night, it doesn’t matter as curtail call remains just beyond reach as in a dream—or, better yet, off-scene in that space once reserved for sacrifices and slayings in classic tragedies. Those were events never witnessed, only experienced as retold, which doesn’t come to bear here anyways because it sounds like they started without them, so what can they do but keep searching?

On The Wall (The Leaking), 2009—a performer also searches for his stage, actually he crawls blindly towards it, lying prone on Canal Street. Dragging his hooded mass inch by inch, the actor traces the system of his own support (namely the sidewalk) in a journey that could double as a pilgrimage, except that it is assuredly only a secular undertaking. Well, mostly, I guess because methodical exertion can actually produce a type of meditative openness. The artist would say an openness to the multiplicity of ‘now,’ presence as present, sensible in ripples and tremors, perhaps of even something more primordial. For my part, I am suspicious of that term—or maybe just view it differently: less perceivable force and more imaginary horizon—an abstract domain a figure can approach only to have it infinitely recede and therein lies the rub. The crawler might suggest a third option still: toiling away, eyes floor-bound, these abstractions fall out of consideration for a type of pragmatic present, where a different realization surfaces mantra-like, if only for its clarity: the performer was performing before the performance began and will be performing after.

The energy harnessed in these undertakings could have very well been channeled into the activity of painting—for the performer, it is one among a number of equivalent conduits, save this one can keep a record of its own making. That provides an alluring purview to be sure, but also poses its own particular kind of problems. Rather than thinking around these, he chooses to work them through as generative limitations, to which he adds a few others. Starting with multiple compossibles on the floor, he builds up layer upon layer, applying paint not with compositional design, but according to a set of physical parameters: begin at the top, continue to the bottom; never use pure pigments only compound hues; work at arms length, never step back for distance; work through self-assigned hours even as bodily exhaustion sets in: stop, next day, repeat.

I’ve always been tempted to describe these operations as adding up to a system, but their function is much less choreographed. Robbed of an endpoint, they simply occasion a body in motion, inviting resistance, push back and, if lucky, a brushing up to the threshold where movement conjured becomes movement visible, where appearance slips into image. To some, the difference might seem negligible, after all the release can happen so quickly. But maybe that’s why he labors so diligently to retard the transfer, slowing the exigencies of the just-perceived to remain in an amorphous state of foreplay. The rest is just a reservoir of marks: practice and the physical index of its duration.

I tend to be an agnostic about these things and I suspect he is too. Then again, maybe it’s not a matter of belief, just the working up to an encounter, which once achieved leaves no other route than to trace the way back. That might be when the process of subtracting begins: a sanding and corroding of built up gestures not to negate what came before but to set the stage for a new beginning.

—Franklin Melendez

Liam Everett, Untitled (Lisana), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Lisana), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Uvira), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Uvira), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Kindu), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Kindu), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Kolwezi), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Kolwezi), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Bakavu), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Bakavu), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Goma), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Goma), 2015 (detail)

Liam Everett, Untitled (Aketi), 2015

Liam Everett, Untitled (Aketi), 2015 (detail)