Artist: Leda Bourgogne

Exhibition title: Mêlée

Curated by: Kristina Scepanski

Venue: Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, Germany

Date: July 15 – October 8, 2022

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Westfälischer Kunstverein

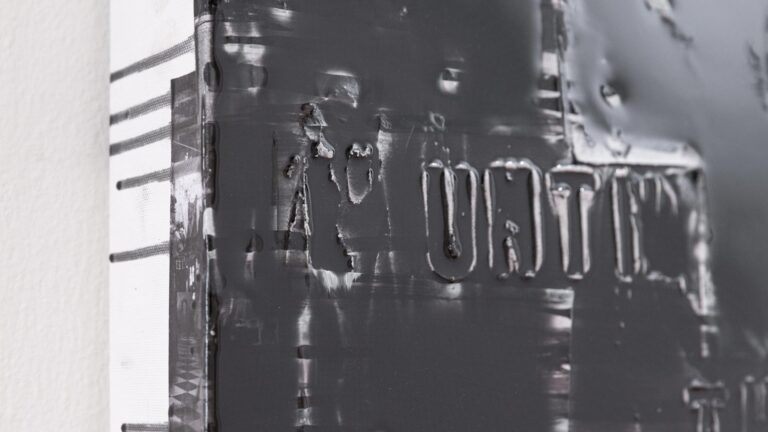

In her exhibition at the Westfälischer Kunstverein, Swiss artist Leda Bourgogne (b. 1989 in Vienna, lives and works in Berlin) brings together a number of new and older works and stages a dialogue between them via a structural intervention. Already visible in the foyer and outwardly into the urban public space, Bourgogne starts with one of the many apparent contrasts that permeate her exhibition, which she pushes until they ultimately resolve themselves. Nine large-format fabric banners, some figuratively painted, some inscribed and adorned with graphic symbols and ornaments, recall demonstrations, rallies, expressions of opinion by a wide variety of religious or political groups. Bourgogne is referring here to the banners of the English suffragettes, who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, campaigned for the introduction of voting rights for women. The Suffragettes not only sewed and embroidered beautiful banners, but also met regularly from 1909 at the Suffragettes Self-Defence Club in London’s Kensington neighbourhood in a space that also offered instruction in painting, sculpture and singing and where self-defence classes in jiu-jitsu were held every Tuesday and Thursday evening. This connection between physical training and the raising of political consciousness interested the artist (and amateur boxer) Leda Bourgogne, since precisely this reciprocal influence of body and mind runs like a thread through her own artistic practice. Thus, she juxtaposes the banners with nine black wall objects based on punch pads used in boxing, and which stand in for a possible reading of the exhibition title: Mêlée denotes a scuffle, a tussle of several bodies, hand-to-hand, extremely close-range combat without projectiles.

From the foyer, brightly lit by daylight, one enters the dark-blue exhibition space, which is split up by ceiling-high dividers – wooden frames covered with fine chiffon fabric – into three sections, each with a distinctly different atmosphere. The entrance is dominated by large wooden panels; painted or shaped into a curve and covered with velvet, they recall the self-conscious gestures of colour field painting, industrial utilitarian objects and the public, regulated space that restrains human bodies and keeps them under control, as the title Rally (18) suggests. The reference to the size and shape of the human body is referenced in Punch Drunk (16), a standardised aluminium tube of the kind used as grab bars on public transport, for example, and the resin cast of a boxing glove.

The dividers prescribe a path for viewers and provide a dramaturgy for their experience of the exhibition. They lead successively from urban space, from public space, into a private, homely (or secret) realm – from the aggressive and combative into the tender and fragile. The dividers are translucent, their construction not only recalls canvases and paintings, but Bourgogne also treats them as such. Similar to human skin, canvas fabrics form a permeable membrane, an immediate contact with the environment, the first filter and first response to influences. In this sense, Bourgogne associates the canvas and the painting as a body and experiments repeatedly with the permeability of the canvas, with the definition of front and back, volume versus surface. She makes use of a wide variety of materials, again positing contrasts: she combines warm, soft fabrics, such as chiffon and velvet with austere, cold materials, such as zips, letter boxes, belts, or a key box. Other “injuries” to the canvas are less mechanical but follow organic forms and have been “mended” in that they have been sewn or patched together.

In the central “room within a room” there is a black leather sofa (which may be used), a kind of stage and a TV Painting that contains the video work Mêlée, a collaborative work with Joanna Krawczyk. Shot in a historic hall of mirrors in Lucerne, it charts another level of meaning to the exhibition title Mêlée: mêler is a French verb meaning to mix, to confuse, but also to unite. It does not then necessarily have to refer solely to a tussle of bodies, but more generally to the state of chaos of many intermingled bodies, whereby the individual body boundaries are no longer discernible. If the punch pads and boxing gloves in the foyer denote the antagonistic, combative aspect of Mêlée, here we see the moment of devoted abandon in the tender intertwining of two women’s bodies. In both cases, a new order can emerge from chaos and from contrast, antagonism. The music, which Bourgogne herself recorded, and the mirrors in the video provide a link to the podium, which, with its mirrored floor, provides a stage for a group of sculptures. Bourgogne has created characters out of objects that have been torn from their contexts and have, in certain instances, become obsolete; these characters have figurative and wholly humorous traits. Black lacquered CD stands from the 1990s have been bent and destroyed – or perhaps liberated from their corseted function – and posit a formal echo to the implied spine in Butterfly Effect (20). Three microphone stands once again unite apparent opposites with slender boxing gloves, nylon tights and fabrics, referencing Bourgogne’s poems presented on the rear divider.

In addition to music and poetry, films, pop culture and subcultures, as well as queer history provide sources of inspiration for Leda Bourgogne. Her handling of these materials and histories may best be described as a new reading, a jumbling up, mêler, a rearranging and presentation in a new order. Thus, in the final room and in an intimate setting, we encounter the French actress Maria Schneider (1952–2011), whose story Bourgogne explored through figurative painting. At the age of nineteen, Schneider became famous more or less overnight for her role in The Last Tango in Paris alongside Marlon Brando (1972, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci). In retrospect, Schneider described the experience, particularly the shooting of the infamous rape scene, as exploitative and problematic, and suffered for many years from the trauma. Bourgogne’s preoccupation here was on Maria Schneider as a distinctly ambivalent individual and also on her personal development, for example, her coming out late in life.

Bourgogne specifically takes up the film A Woman Like Eve (1979, directed by Nouchka van Brakel), in which Schneider plays the lover of a married woman. The portrayal and outcome of this love triangle became a kind of benchmark at the time in the recognition of queer life and love choices far removed from the moralising attitudes typical of the time.

Leda Bourgogne’s exhibition Mêlée revolves around the concept of self-defence. She understands the term not only as being able to defend oneself physically, but also in the sense of a defence of the self, of one’s individual identity and integrity. At the same time, she is concerned with the interfaces between body and mind; namely, showing the proximity of thoughts and feelings, and that well-being, pain, desire, longing always have both psychological and physical components and influence one another.

In this endeavour, she draws on the writings of French philosopher Elsa Dorlin, who, in her award-winning book Self Defense. A Philosophy of Violence writes:

“Self-defense was effectively becoming a total art, due not only to its wide range of practical and effective martial techniques, but also to how it contributed to new practices of self that that entailed transformations at once political, bodily, and intimate: by freeing the body’s motions from cumbersome clothing, by unfurling in movement, by appropriating familiar objects and turning them to different uses (umbrellas, pins, broaches, coats, heels) and by bringing muscles to life. By training bodies that inhabit and occupy the streets, that move from place to place and find their balance, feminist self-defense opened up a new relationship to the world, a different way of being.”1

By appropriating the aggressiveness of boxing and the capacity for physical self-defence both artistically and physically, Bourgogne empowers herself as it were to also understand and defend her own fragility, her delicacy and sensitivity and her desires as something worthy of protection. And quite incidentally, she thus resolves the supposed contradiction of these two worlds and encourages us to do the same – to find an access to our combative bodies.

Curated by Kristina Scepanski

1Elsa Dorlin, Self Defense. A Philosophy of Violence, trans. Kieran Aarons (London Verso, 2022), p. 45. Originally published in French as Se Défendre: une philosophie de la violence (Paris, 2017).