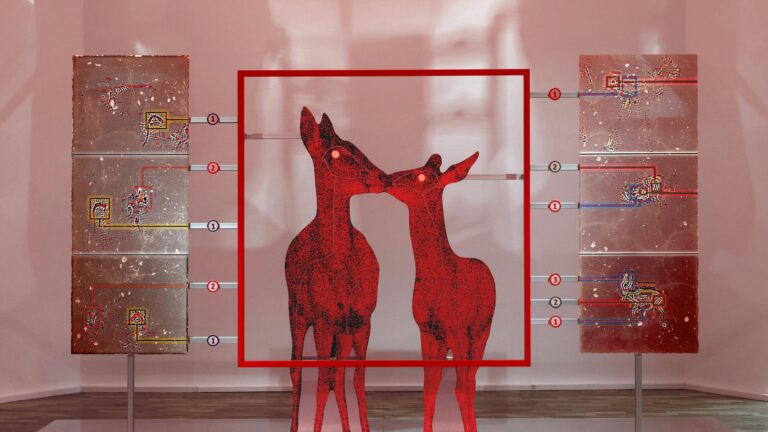

Artist: Justin Liam O’Brien

Exhibition title: Damned by the Rainbow

Venue: GNYP, Berlin, Germany

Date: July 4 – August 15, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and GNYP, Berlin

Every proximity entails a vast array of sentiments. From the sublime to the dreadful, from joy to boredom, and many others, lost in a grey zone, untranslatable. The tension between two bodies compressed in the same room, in the same routine, imprisoned in the same dreams—the ambiguity of this close connection is unmatched; there can be no substitute to the experiences shared by the contact of the flesh, the meeting of the souls.

The central theme of Justin O’Brien’s works is not so much the nearness between lovers, the theatre of affections with which Eros inflicted us—hopeless expectation, calculated indifference, confident vanity, desire—, as the sphere in which these sentiments develop. Confined in a suburban house, compressed in a smoky bar, late at night, lost in the indistinct curvy zone of deep human connection, the lovers seem trapped inside very distinctive places. Nonetheless, it is there, in the concrete counterpart of their dreamy beings, that life unfolds, dancing in a blue rug, engulfed by an armchair, posing in a chaise longue.

In this sense, it would be partial to understand O’Brien’s paintings as having to do merely with queer sexuality. As the artist explains, “it actually has very little to do with this. Sex momentarily comes into play, as it does in life. I think the majority of the work is rather about an intensity of feeling. Intensity in the quiet moments of domestic life. About experiencing an extreme emotion within the mundane. The moments are queer because I am queer.” At the end of the day, the universality of love, regardless of colour, sexual orientation, and nationality, imposes itself. Eros has no eyes for identity politics. Below his wings, we’re all equal.

Interestingly enough, even though these characters are all completely immersed in their own universe, they appear to be aware of our presence. They pose to us, looking directly at our end of things. Were we expected to sit at that table? Without realizing it, we’re stepping on the same rug, sitting on the same sofa. The interaction of gazes—between us and the characters on the paintings, and between themselves, the lovers—is unstoppable. Everything is private, but still very much familiar. Perhaps we have also experienced moments such as these, as ambiguous and full of promise. Moments transformed by the compelling watch of a loving gaze, in all it contains of care, pressure, and menace, as the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva described, a hundred years ago: “black as—the center of an eye, the center, a blackness that sucks at light. I love your vigilance.”

by João G. Rizek

***

The culture is in love with using identity as a descriptor. What used to be the domain of annoying academics and precious curators has metastasized across the Internet, the pinned post of woke Twitter personalities and the de facto lede for every publication rushing to make amends for their spotty records covering minorities. “Black joy,” “the trans experience,” the “female gaze.” These terms are ostensibly meant to honor the subjectivity of their diverse audience, to recognize the unequal stake these groups have had in shaping our collective record, and to undo the harm of their historical erasure. But for their good intentions, these labels risk marginalization as much as they seek to address it, parceling off their subject’s emotions into realms of feeling that aren’t simply human but uniquely identitarian.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in the case of white gays, who, having been welcomed into the mainstream, find themselves stranded between a radical past and all the privileges and deprivations of being just another client of late capitalism. In keeping with the current trend of critical theory eclipsing people talking openly and honestly about their feelings, “queer desire” has become one of the most evoked terms to discuss the work of contemporary gay artists. This is usually in reference to the overt sexuality of their work, the palpable longing and ambient horniness a painter demonstrates on the canvas for his idealized subject. But “desire” in Queer Theory has broader implications than simply wanting a boyfriend. In its most radical conception it’s about citizenship, about wanting the world as open and hospitable to difference as possible, about ultimately being free from wanting anything.

It’s fitting that Justin Liam O’Brien’s latest show, “Damned by the Rainbow” arrives in the wake of history’s most contentious Pride Month, when the LGBTQ community has never felt more pressure to clarify the kind of society it actually wants to inhabit. The title is a line from A Season In Hell and reads like a rebuke to the warped priorities and false triumphalism that has marked Pride up to this point, where “queer desire” has been treated as less of a revolutionary wish or state of being than a weepier kind of consumer demand.

“Damned by the Rainbow” is about desire as an existential condition, a constant inconvenient texture of life that no boy, app, or feat of representation will ever cure. O’Brien’s subjects feel desire but don’t know where to place it. They dance, they fuck, they stare longingly at their phones. They want and hurt badly for wanting. They’re often too stuck in place to appreciate the notion that they’ve “arrived.”

Like his heroes George Tooker and Hugh Steers, O’Brien has an eye for capturing the loneliness of a crowded room and the alternately still and charged air that hangs between two lovers. Where his previous work featured blown-out swaths of black paint, O’Brien has tightened his grasp on color, deploying it to create some of his most evocative paintings yet. Riffing on pieces by Steers, Ian Lewandowski, and Efraim Zelony-Mindell, O’Brien has created a suite of lush portraits of people caught up in their anxieties and lit from within by passion.

Contrary to his title, O’Brien’s work is fundamentally redemptive, holding moments of yearning in suspense and revealing them for all of their humanity.

by Harry Tafoya