A practice is defined as any routinized form of behavior that is composed of different interconnected elements: bodily activities, mental activities, objects, uses and other forms of knowledge such as meanings, practical knowledge, emotions and motivations. The existence of a practice depends on the specific interconnection between these different elements.

It is through its performance, through the immediacy of action, that the practice as an entity is completed and reproduced. Only in the doing do the elements of a practice come together, and it is in their successive re- creation that social orders are sustained and stabilized. However, it is precisely those moments in which these elements can be reconfigured and the social order altered.

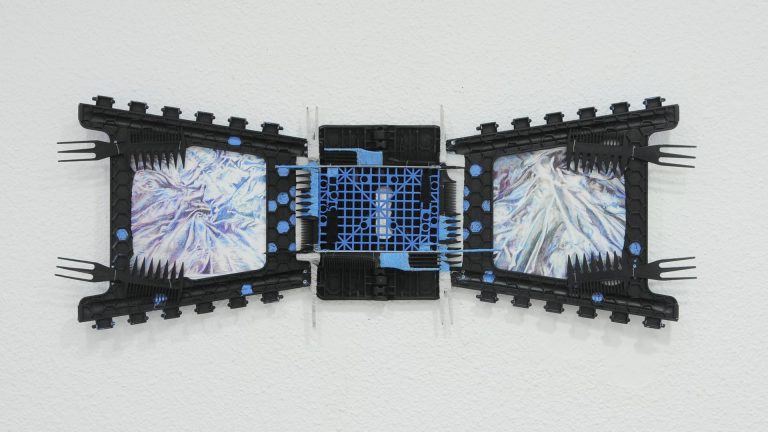

Seen through this prism, sculpture is itself a practice. With its historical genealogy, its aesthetic problems, materials, techniques and associated knowledge. Here, however, sculpture is not understood as an aesthetically autonomous space. Sculpture is not thought of as a practice in itself, but as a point of contact, as a space of reconfiguration through appropriation, reproduction and assemblage of materials, meanings and competencies1 of other pre-existing practices.

In The Nightmare of Participation Markuss Miessen introduces the concept of crossbench praxis as a model for generating critical space. By this he means making intrusions into disciplines, or rather practices, in which one is not invited in order to deliberately open up new spaces and question ways of doing.

In our understanding, June Crespo’s sculpture participates in these dynamics of reordering. A reconfiguration from the making, from the equating of functional use and misuse, a close encounter with the materials and their affective aspects that enable the emergence of the unthinkable.

Seen from the perspective of practices, from a sculpture that equates materials, meanings and processes from a disparate proximity, June Crespo’s assemblages problematize the distinction between archive and repertoire established by Diana Taylor2. They are not either one or the other but the in between, being tangible and stable while containing processes, gestures and practical knowledge that are articulated through experience.

[1] In The Dynamics of Social Practice, Shove, M. Watson, and M. Pantzar propose to understand practices as ways of doing and/or saying that arise from the spatio-temporal interrelation of three elements: competencies, meaning and materialities. Materia- lities encompass the totality of tools, infrastructures and resources involved in the realization of a practice. They are constitutive of practices, they define the possibility of its existence and its transformations. Meaning refers to the set of affective aspects, valuations and cultural repertoires on which the meaning and necessity of a practice is established for those who carry it out. This includes, among other things, the set of meanings, beliefs and emotions associated with a specific practice. Competencies refer to the set of practical knowledge and skills that make it possible to carry out a practice.

[2] In The Archive and the Repertoire, Taylor establishes a distinction between archive and repertoire where she attributes to the former a material form and to the latter an ephemeral form of transmission based on We believe that this distinction does not reflect the complexity of social practices, where meaning derives from a relationship of interdependence between materials and their uses.