The exhibition restages a series of works that Julia Scher realized in 2000 at the Andrea Rosen Gallery in New York. The installation is centered around microwaves—literally and thematically—both as microwave ovens and as electromagnetic microwaves. These are set in an almost techno-alchemical laboratory in the exhibition space—on workbenches, in various display situations, dismantled and transformed into fantastic media chimeras. In the context of Scher’s examination of the entanglements of technology, society, and desire, microwaves emerge as interfaces, allegories, and ur-appliances of the information age.

The exhibition is also closely connected to Julia Scher’s teaching position at MIT in Cambridge. Here, in the legendary and now-demolished Building 20 and its so-called “Rad Lab,” the basics of microwave radar and surveillance technology were developed, making MIT the largest wartime R&D contractor of the U.S. and prototyping strong institutional links between government, industry, and academia. Originally intended only for the duration of the war and six months thereafter, the building was a dilapidated monument to the economic expansion of the state of war, infamous as an interdisciplinary hub of progress in the post-war, pre-9/11 U.S. Building 20 had its hand in basically everything: from the rise of the household microwave oven and the observation of cosmic microwave background radiation, to information technologies, modern linguistics, 3D printing, and early student hacker culture.

Microwaves permeate everything; they make molecules vibrate from the inside out. They are omnipresent and invisible, serving as the spectral and clandestine medium par excellence—from wireless communication to psychotropic warfare (see “Havana syndrome”) and pulse weapons. It is said the 21st century might become the era of electromagnetic warfare. Equipped with microchips for a precise timing function as early as the mid-1970s, the microwave oven was a pioneering appliance of an everyday life integrated into electronic networks even before the PC. Microwaves, hazardous and domestic, are both emblem and carrier medium of the control society. They represent the invisible realm, a light beyond human perception, and the ether of a military-technological-libidinous complex that Julia Scher brings into form in her work in all its parasitic conditionalities.

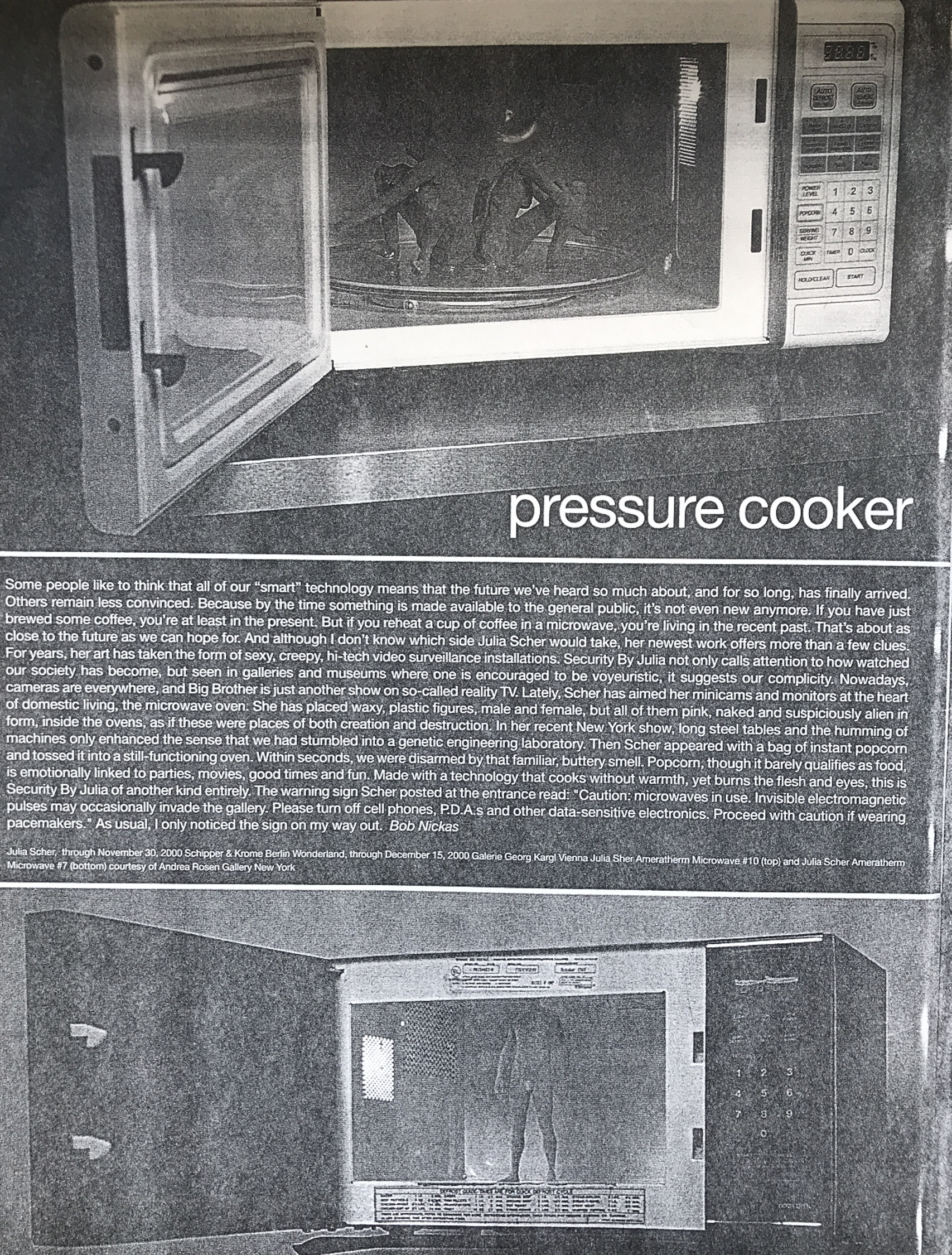

Lined up and rearranged, they stand and hang in the installation—real microwaves, comic-like mock-ups—all branded in Julia Scher’s inviting pink CI of ambivalent allure. The devices appear to have mutated; they house diverse media, various electronics, cameras, monitors, projectors, VHS tapes, and golem-like figures, homunculi produced with early 3D printing. The microwaves seem to sprawl and proliferate. Although the ovens are virtually defused with their magnetrons removed, the room is fundamentally marked as unsafe, with some of the doors of their inverted Faraday cages opened. The microwaves are data emitters, and they leak.

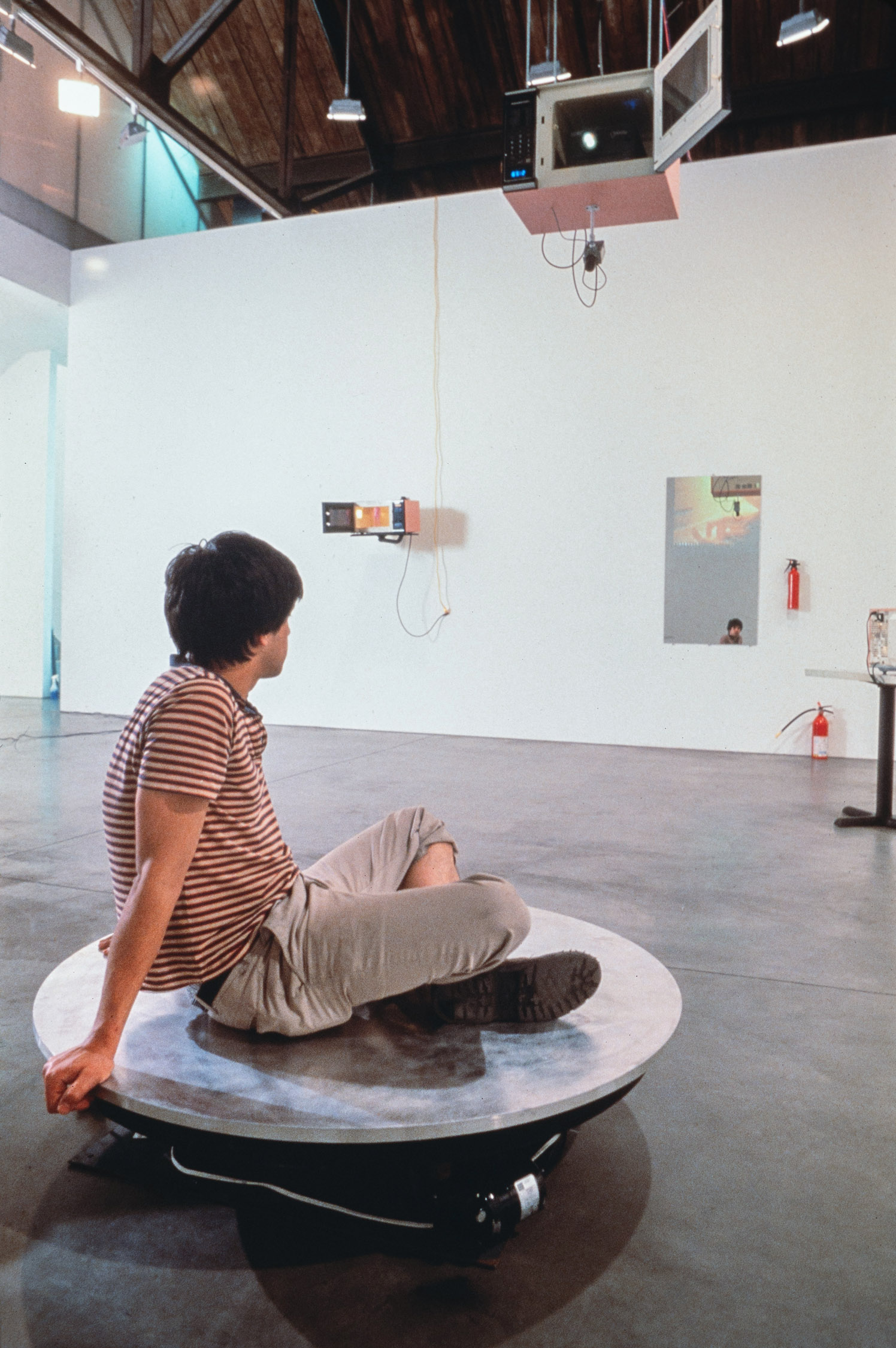

The ominous, enigmatic arrangement also invokes a Hollywood B-movie set, a glamorous twilight. The works play with different types of presentation—the microwave is fanned out as a staging device and screen, which it actually is in the kitchen. It presents itself as a screen, as a home for other screens, as a camera, and as a projector. A rotating platter is enormously enlarged on the floor of the gallery space, forming a stage and an inevitable cul-de-sac of the installation. The viewer is literally turned into content. And the gallery space itself becomes a microwave, a danger zone, a portal of transformation. In this matryoshka-like, circular logic of Julia Scher’s work, in which everything is nested and mirrored, the works form feedback loops in which viewers, as one of many machines, are also looped in, ensnared, and caught, like a mouse in a trap.

What does it mean for a person, for society, to have been turned from the raw to the microwaved? In “ameratherm,” the relationship between modern humans and data streams is both threatening and seductively sensual. But it is also intangible. Tessa Laird refers to this ethereal sphere of information, the light beyond human perception, as “pink data”—that penetrate and impregnate. She connects this with a feminine-coded, lustful gnosis—a techgnosis, so to speak (Erik Davis). Not only does “pink” etymologically come from ‚to pierce,‘ ‚to perforate,‘ it finds the harbinger of modern data ecstasy in Philip K. Dick, who, according to a well-known incident, received inspirations of inhuman, all-encompassing wisdom in the form of pink-colored radiation. He spent the rest of his life describing those “beams of pink light” as “blinding him and fucking him up and dazing and dazzling him, but imparting to him knowledge beyond the telling.” Dick himself wasn’t sure whether the source of the epiphany was God, an alien satellite, or Soviet scientists whose psychotronic microwave transmissions crossed his apartment.

The four channel spoken word track refers to this possibility of ‘acoustic psycho correction’ through microwaves and is itself almost subliminally suggestive in the alluring tone of the artist’s voice. Also known as ‘microwave hearing’ or ‘artificial telepathy’, this interference of human brain waves with a potentially behaviour-altering effect is being researched by the military in particular as a ‘less than lethal weapon’. And finally, the text refers to the exhibition’s recurring term ‘water hole’. In the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, SETI projects concentrate primarily on radio signals in the ‘cosmic waterhole’, a frequency band with relatively little interference that lends itself to communication with alien signals, a virtual area for interplanetary collective gathering, so to speak. And in this sense, the exhibition also directs the microwaves territorially outwards and the exhibition turns the logic of surveillance into the otherworldly, the interstellar. Perhaps not only to expand its control system and the exhibition space extra-planetary, and not only to find knowledge, redemption and love, like Jodie Foster in ‘Contact’, and perhaps not only as an expression of cosmic loneliness, but perhaps also because every act of communication is a strange and only partially human affair to begin with.

— Baptist Ohrtmann

Julia Scher (b. 1954, Los Angeles) lives and works in Cologne. During the last four decades, her work has been shown widely across multiple renownded international venues, such as Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg; Ortuzar Projects, New York; Esther Schipper, Paris; Empty Gallery, Hong Kong; Drei, Cologne; Museum Frieder Burda, Baden Baden; Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, Vereinigte Staaten (all 2024); Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach; Kunsthalle, Zürich; Museum of Modern Art, New York; (all 2023). Work of hers is furthermore included in the public collections of Museum of Modern Art, MoMA PS1, Guggenheim Museum, all New York; SF MoMA, San Francisco; MIT Museum, Harvard University, both Cambridge; Nevada Museum of Art, Reno; Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Champaign; Ballroom Marfa, Texas, all USA; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach; Museum Wiesbaden, all Germany; Neue Galerie, Graz, Austria; MAMCO, Geneva; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Le Consortium, Dijon, France, a.o.

cables, 53 × 93,5 × 63 cm (20 7/8″ × 36 3/4″ × 24 3/4″)