Artist: José Fiol

Exhibition title: Heart-shaped box

Venue: Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca, Spain

Date: September 21 – December 3, 2019

Photography: Grimalt de Blanch / all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca

José Fiol’s painting is offered as a fragment of many things. It’s as if the artist was dedicated to measuring time, looking in the rearview mirror and trying to pick up on some tensions and stories that remain suspended. It is not about what is left over, but what is missing. The remains of that painting of which Ángel González spoke. Because if it were necessary to approximate José Fiol’s painting to other contemporary artists, we would have it relatively easy when establishing analogies: the frames of Eberhard Havekost; the chromatic and suspensive restriction of Michaël Borremans; some doses of the subjectivity with which Elizabeth Peyton portrays her celebrities, including Kurt Cobain himself, and so on. We could continue the list with a series of artists that follow a line of influence that Jordan Kantor defined as “The Tuymans Effect” in a text published in Artforum in 2004. For Kantor, Tuymans – following Richter’s thread – inaugurates a special mode of “see and represent” that will have a great resonance in later painters such as those mentioned and others such as Magnus von Plessen or Wilhelm Sasnal who, like Fiol, radically oscillate the scale of their paintings. The crude way of illustrating, the use of film and photographic sources, the use of reduction techniques, his inclination for historical subjects or the commitment to a subject that leads him to investigate and know in depth before painting, are shared “ways” of these and many more artists who, far from situating themselves in a kind of mannerism, speak of common concerns – those remains – from the turn of the century until today.

José Fiol’s gaze remains, therefore, prey to other pictorial views with which he shares concerns and formulas. It should be clarified for those who do not master the history of painting well: all the great painters of history are astute observers able to devour the best of their predecessors. José Fiol is no exception, but it is also that use of appropriation, like a model who lets us see his way of mastering the painting, picking up on its internal problems, its composition, its framing or its relationship with the universe of other disciplines. We are talking about one of those artists who work the emotional sense of incorporating photography into painting, because he uses reality as support to introduce fiction. In José Fiol there is an intention to represent the irrepresentable of a theme that, being a reality, can only be objectively based on the fiction of the artist himself. In photography, it is reality that becomes an image. However, when it is painted, it is the image that becomes reality. It seems obvious, but it isn’t. Therein is inserted the radicality of Andy Warhol and his photographs printed on canvas. Gerhardt Richter goes one step further when taking photography with the painting, but especially when doing so while looking for that which is blurry and uncomfortable, blurring the contours and distorting reality, which in many cases eliminates and smears. It is in this enigma that José Fiol’s painting is based, which always tries to make detours, seeking the latency of the image, the suspension of its history. The everyday and the historical intermingle to become traces that combine in a kind of representation. It is not a “return to order”, but to give virtuosity and pictorial quality an appropriate time to settle a theme, in this case in the form of a particular tribute to some of his elective affinities.

That is why Luc Tuymans spoke of painting as a means of delayed expression; also as an “authentic fake.” In both cases we feel a closeness to what José Fiol seeks, approaching the mystery of the real, to the shifting reality that shows while hiding and omitting, condensing the image, suppressing the color, skewing the framing. I understand that it is not about apprehending the realistic character of the photographic image but its intrinsic photographic character. In other words, more than a composition, José Fiol paints the cut of that previous composition of the photograph and that supposed delay of which Tuymans speaks and derives in a deferred temporality more typical of the cinematographic.

The Heart-Shaped Box project includes a small historical fact as a starting point: when Nirvana’s leader, Kurt Cobain, went to meet his idol William Burroughs in Kansas. In that meeting, which happened in 1993, the singer proposed that the writer participate in the video clip that gives title to this sample, although the latter declined the proposal. José Fiol, also a musician and nothing foreign to the legacy of both, as well as to the drifts of many of the countercultural artistic proposals that unite them – we cannot forget that Burroughs has confessed fans like Patti Smith or David Bowie – takes this moment to unite them in a circumstance that will mark their lives: opioid addiction and the effects they can produce, specifically the protanopia that leads to the loss of vision of the colour red and the predominance of green, blue and yellow, something that literally leads to paint in this series, eliminating the range of reds, oranges, etc. José Fiol starts with the photographs of that meeting – images that will not come to light until years after the death of Kurt Cobain and made known by his wife, Courtney Love – and deforms and stretches them with the paint. Thus, in the literary we could bring it closer to Agustín Fernández Mallo and to that idea of the past as an active waste capable of projecting in the present to build it. It is there where the metaphorical and the poetic are built. Because one of the most attractive aspects of José Fiol’s painting is the particular way of translating reality into something dense, incorporating documentary records to generate an elastic and veiled atmosphere, but also absurd, using a certain humor to blur reality and its historical linearity.

In this series he paints, among other things, the filming set of the aforementioned video clip, but also some of the guitars of Kurt Cobain, aware of the rocambolesque story that will happen around some of them at the artist’s death. Because the narrative in José Fiol’s painting is more an echo than a voice itself. It is a painting that plunges us into the details, not based on an image of the real but on that reality mediated by screens and lenses, movies and myths. A painting after the painting that can be born from the question of why we need more painters. Although of course we need the polyhedron of painting in a world like this full of images, because in artists like José Fiol the painting cannot be defined as a reflection of reality but as a reality that arises from a reflection, if we paraphrase Godard. Hence, he is interested in both fiction and the disturbing, with an atmosphere close to other painters such as Kaye Donachie, but also to Velázquez’s baroque style; just think of the Calabacillas Jester and his blur, which is not at all an unfinishing of the piece, but that blurring with which Velazquez represents the poor vision of the protagonist and his mental retardation.

José Fiol, like Velazquez, plays with that visual transposition. As spectators we are challenged to face the difficulty of perception. I think about David Lynch and how he concentrates the tension on the juxtaposition of thematic elements, getting different layers of meaning. Also in the lack of linearity of their stories, their various temporalities, more typical of the time of reception than of the plot, or the planes of detail that interrupt as much as they enrich the flow of history. Lynch is also a mannerist who phagocytes his affinities with humor to distill everything in a sort of kitsch, but above all a master of how to apprehend the dramatic density of colour, embracing the greys, the empty spaces.

But we could also talk about the clinical writer Oliver Sacks, who in his book An Anthropologist on Mars, tells how he received a letter from a blind painter in colour that described that colour blindness: “My brown dog is dark grey. Tomato juice is black. ” On one occasion he was depressed by a rainbow, which he saw only as a semicircle without color in the sky. He later discovered that he could make black and white pictures, and make them very well. Sacks reveals to us how colour is not a trivial matter. It was not for Goethe, nor for Spinoza or Schopenhauer, nor for Wittgenstein. And much less in painting, which concerns us. Hence, José Fiol enters into its absences and dominances as a key element to give thread to a story. A good example is Blue, by Derek Jarman. A film in which the only image consists of a monochrome blue, constant from beginning to end, on which an autobiographical text of the author himself, who had contracted AIDS and developed this project when he was in a very advanced phase of the disease. There is thus a mixture between formal rigor and political-existential anger, between the structural cinema of the sixties and the confessional. Without image, blue contains them all. As in the series of recent paintings by José Fiol we can see beyond and reconstruct a story from the chromatic metaphor, a successful symbiosis between form and content. If the blue in Jarman is a metaphor for his blindness, here the loss of the colour red is a metaphor for addiction, but also for the attractive excesses of more than one generation. Always hiding the brushstroke, erasing the origin of the painting, watching the story to assume it as a rumour, as an enigma, as an overlapping speech.

David Barro

(Translation from the original text in Spanish)

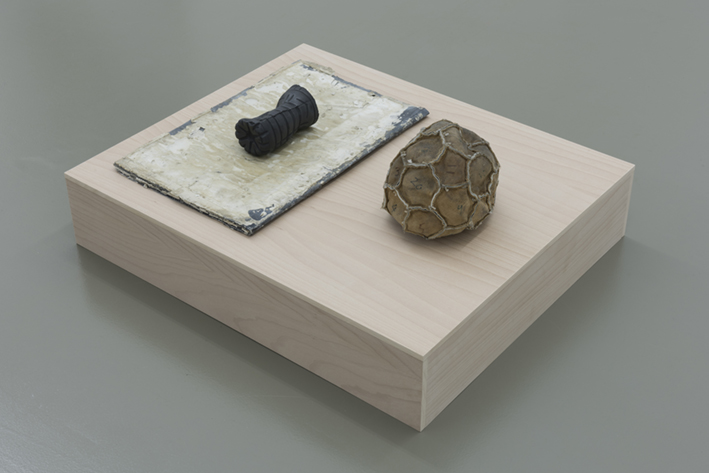

José Fiol, Heart-shaped box, 2019, exhibition view, Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca

José Fiol, Heart-shaped box, 2019, exhibition view, Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca

José Fiol, Under the silver lake (2019), Oil on canvas. 160 x 170 cm

José Fiol, Heart-shaped box, 2019, exhibition view, Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca

José Fiol, Blue (2019), Oil on canvas. 27 x 22 cm

José Fiol, Something in the way (2019), Oil on canvas, 190 x 150 cm

José Fiol, Heart-shaped box, 2019, exhibition view, Galería Fran Reus, Mallorca

José Fiol, What’s the frequency (2019), Oil on canvas. 190 x 130 cm

José Fiol, Lake of fire (2019), Oil on canvas, 190 x 150 cm

José Fiol, Heart-shaped box (2019), Oil on canvas, 27 x 22 cm