Artists: Vanessa Disler, Tiziana La Melia, Lucy Stein, Charlott Weise

Exhibition title: Johnny Suede

Venue: Damien & The Love Guru, Brussels, Belgium

Date: March 26 – April 29, 2017

Photography: Kristien Daem, all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Damien & The Love Guru

Johnny Suede is a collaborative work by Vanessa Disler, Tiziana La Melia, Lucy Stein and Charlott Weise.

“The stage started right at the front doors, inscribing architecture with storytelling” writes Paul Beatrice Preciado in Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics. Beyond the doors and inside the “ultra private haven was in fact overexposed territory, with the price of admission to that unusual place was to become an (almost always) anonymous actor in an erotic film with no beginning and no end”. Two days ago, Francesco Clemente appeared to us as a “crepuscular avuncular presence in a parsnip,” and following our instincts (as serendipitously, it also happened to be his birthday) we decided to bring out the accents in the parsnips eyes.

The exhibition’s title alludes to Brad Pitt’s character from the film Johnny Suede (1991), who appears done up in a 50s look from head to toe, a kind of male version of the “bimbo” (Italian for baby, North American for dumb blonde) who is chasing clichés. After leaving a nightclub, a pair of suede shoes falls from the sky into Johnny’s hands. Fetishizing the shoes, he declares to now be “complete”. This transformation into Johnny Suede gives him the confidence to pursue his fantasies, to feel ultra-connected to his body, the courage to introduce himself to a girl, the excitement to get serious about starting a rock band. In this role young Pitt is an ingénue, still in search of his identity. And suppose Johnny is in pursuit of a language and style, and that to assume consciousness is at once to assume form. If the details of a consciousness take form as a pompadour or the diamantes on his shoes, or the complexity of love which forces the mind to constantly re-describe itself, what does it mean, we wonder, to be styling a mind after furniture?

In French, the word for furniture is meuble, meaning “moveable transportable goods”, from spoons to tiles to women and so on. From the bed we transmute into the horizontals, and back to crawling on all fours, homo horizontalis, the material of our work spills off the bed and onto the floor, and from the floor it is reified as fabulous bibs on the wall. The spin becomes a curl. The iced figure melts into hands with spiral fingers. Control turns adolescent.

From within Damien & The Love Guru, a storefront site, we pool our collective energies, exposed, spread eagled, rolling in the hay, day and night, for all to see. We have been struck by public responses to our work in particular from young female residents of the neighbourhood. We have incorporated these as titles and guidelines on how to proceed. For instance, the observation by a little girl passing by, who utters “femme de nature” or a resident living upstairs, comparing our enveloping chaos of day five to “a female ward in an insane asylum”. Over the course of seven days, our ambition to simulate a bachelor pad went awry.

As the focal point to the exhibition is the least imaginative of all forms of architecture, whose dual purpose is for sleep and to designate a room as a room that is quiet, the bed. Preciado describes Hefner’s circular, ambient, rotating bed as “[articulating] a single module, and the recording and multimedia station [doing] away with the traditional antithesis between passivity and activity, sleep and wakefulness, rest and work. No longer synonymous with sleep, the bed became a topos of never ending, mediated waking, anticipating and erotizing a new form of proximity and spectacle of exposure,” created by “our electronic involvement in one another’s lives”. The site of the bed as creative nest signaled a shift between the literary tradition of death bed literature (Anne Boyer) or artists working post accident (Frieda Kahlo) or the associations with melancholy, hypochondria, sickness, and inertia (Marcel Proust), however, in Hefner’s mission to reclaim domestic space, he manifested a new kind of sovereign masculinity, typified by supine postures in ritzy relaxation, meshing sex, work and culture. This horizontality emphasized the attitude new at that time (and of our time, quietly waking up and scrolling through headlines from bed). Russell Miller described the rotating bed as the warning sign of what would be later called Peter Pan syndrome: an illness of a regressive and narcissist adult who takes refuge in an artificial childhood: “a man who refuses to grow up, who lives in a house full of toys, who dedicates a good part of his energy to playing child games, who falls in and out of love like a teenager, and who gets upset if he finds curds in his sauce.” Miller considered Hefner’s refusal to get out of bed as a pathology, a reflection of a physical handicap and a sexual compulsion that forced him to live in a horizontal position and avoid the real world, “spoiled and safe in his sensualized community.”

Consider the “relationship between power and visual pleasure generated by the act of lying on a rotating bed, to occupy the centre of the universe”. Consider the “repeated image every time the bed rotates, installed in the center of the universe that can be controlled, and where you are the only monarch that no one can expel, always diving into yourself. . . . After each new rotation, the nirvana, the ambrosia, here, in the center, so that everyone can see you, the lighthouse.” The conception of the rotating bed, “might be more discretely linked to royal scenarios of power and the eroticization of the public body than to the verticality of North American masculinity in the 1950’s, became an electrified hybrid of the lit de justice and lit de parade, which conferred power and at the same time referred back to traditional female sex workers’ practices of public display of sexuality.”

La femmes nature’s mattress is made of hay, that eternal substance that peasants or servants spin into gold, inverting inside and outside realms — the industrial to the domestic…compressing time for a soft edged voyager sans voyager, hallucinated reality where industriousness is fabulous, fabricating, fabling, looping and moldable. The mantra guiding our spiral into clichés, is “anonymous was a woman”. Anonymity as a subject requires deeper consideration than what there’s time for here, considering that there is only so much one can properly consider while moving between liminal thresholds of articulation, and material dissolve. Anonymity here focuses on the impersonal gesture of a very generic female hand and the sharing of (intellectual) property.

Acknowledgements:

Paul Beatrice Preciado, Pornotopia: An Essay on Playboy’s Architecture and Biopolitics; Viginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own; Tom DiCillo, Johnny Suede; Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy; Henri Focillon, The Life of Forms in Art; George Wagner, The Lair of the Bachelor.

Press Release, 2017, Hay, personal affects, marine trim on wooden motorized bed, 175 x 175 x 40 cm

Press Release, 2017, Hay, personal affects, marine trim on wooden motorized bed, 175 x 175 x 40 cm

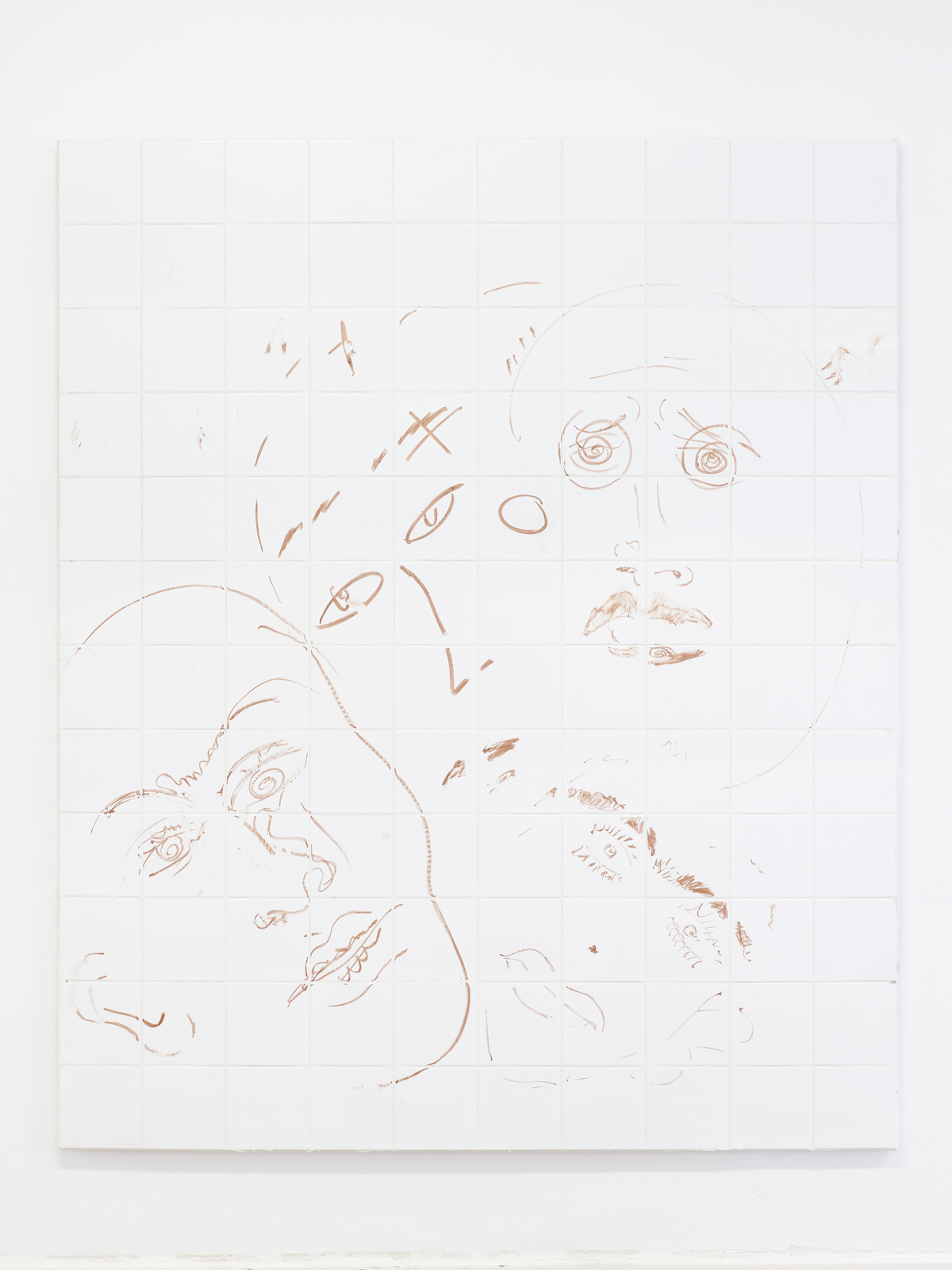

Stalker, 2017, Pastel, pigment, binder, flashe on canvas, 150 x 190 cm

Angry Birds, 2017, Pigment, acrylic, hay, silicon, pastel on canvas, 150 x 190 cm

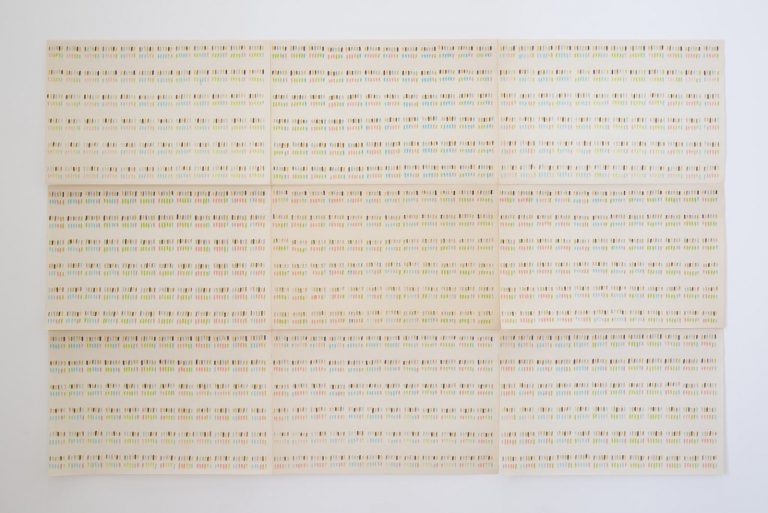

Contour Clubbing, 2017, Tile, Park Avenue, lipstick, grout on plywood, 160 x 180 cm

Dark Feminine Time Code, 2017, tile, paper, charcoal, sand paper, plates, acid silvia, lipstick, flashe, grout, canvas, 150 x 190 cm

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, 2017, Galliano ripped dress, coffee, spray paint, willow garden fence, zap straps, orange peel, glue, wood, flashe, pastel and canvas, 165 x 200cm