Artist: Johanna von Monkiewitsch

Exhibition title: 9 to 5

Venue: Berthold Pott, Cologne, Germany

Date: November 17 – December 20, 2022

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Berthold Pott, Cologne

Johanna von Monkiewitsch’s Light Sculptures, or: A Shift in Perception

In a conversation with Johanna von Monkiewitsch about her work, we also talked about her life story. It is sometimes tricky to bring in aspects of an artist’s private life when analysing their work, because it can all too easily take on the flavor of facile psychologising. But Franz Erhard Walther once said to me: “I grew up amid the ruins of war, and what I saw naturally left a mark on me.” So perhaps it is a question of where to focus one’s gaze and what it takes in. Some things certainly cause a bigger impression than others. We got to talking about the sea and the light, because Johanna von Monkiewitsch has lived in Los Angeles and spent a lot of time in Italy. We spoke about the vastness of the sea, which leaves ample space for light, about the perpetual and sometimes dazzling reflections on the water’s surface but also its glistening swells – two elements that are easy to grasp with the eyes but which are constantly in flux, hard to hold on to. Light consists of electromagnetic waves and is therefore basically matter without matter, able to penetrate transparent materials such as water, glass, or plastic. As soon as it is there and illuminates our surroundings, it determines the character of the atmosphere as well as our perception of objects and time. Light lends a specific tonality to our days and the quality of our memories. In short, it has a powerful influence on what we see, and even more so on what we believe. Might we even say that light is a “magician” that creates illusions while it reveals the world to us? In a series of minimalist works that combine solid materials with a light projection, on view at Kunsthalle Bremerhaven in 2021, Johanna von Monkiewitsch examines the phenomenon of the moment when light strikes an object. Drawing on Goethe’s treatise on color (1810), in which he analyzes how altering the hue or saturation of a tone can evoke a completely different feeling, the artist explores how light affects our perception, to the point of unsettling our view of concrete things. Regarding von Monkiewitsch’s work through a phenomenological lens, we can even say that it creates a kind of perceptual disturbance that chal lenges our preconceived notions about the truth of things themselves.

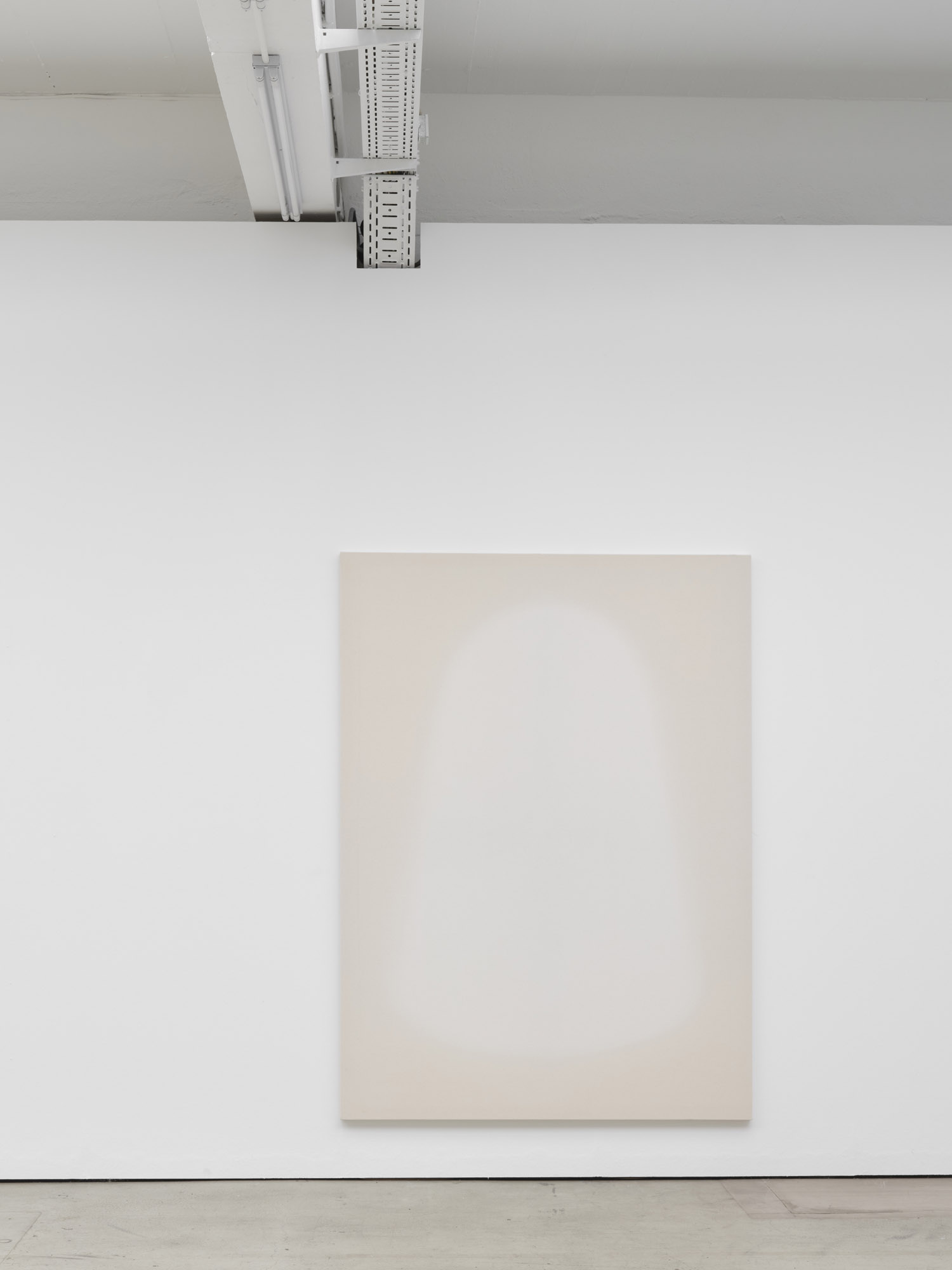

In general, von Monkiewitsch’s work deploys a limited number of elements: paper on which a color reflection or shadow can be seen; a light installation that projects filmed sunlight onto the wall or allows it to move through the room; or concrete reliefs in which one surface has been covered in pigment and whose shape corresponds to the shadow the relief casts on the wall. Some of the sculptures on display at the Kunsthalle Bremerhaven consist of one or two solid blocks of marble or foam material (some of them wrapped in plastic film) and others are flat wall objects made of MDF, wood, or fabric illuminated by the light of a video projector. The materials are monochromatic: white, beige, or black.

The forms are simple rectangles, standing on the floor, or leaning against or hanging on the wall. The nature of von Monkiewitsch’s works and her choice of geometric and uniform structures place her in direct succession to American Minimalists such as Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, and Robert Morris. The latter’s works Untitled (L-Beams) from 1965, three white Lshaped geometric sculptures arranged on the floor at different angles, and Two Columns from 1961, two rectangular white columns, one standing upright, the other lying down, perfectly illustrate this connection. With his elementary works conceived on a human scale, Morris sought to demonstrate how our perception depends on the associations we make and our prior knowledge, on our learned experience of space and of the physical characteristics of the elements (how materials absorb light, the effects of gravity, their weight and proportions). Here, it is worth recalling the importance of Maurice Merleau Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception (1945) for the approach taken by the Minimalists. In general terms, the French philosopher describes in his book how, even prior to any cognition, our perception is influenced by what we know, and that a series of automatic, unconscious responses underlie our behavior and thoughts. Ultimately, it comes down to comprehending how a particular form or object relates to ourselves (as beholders), since our worldview is fundamentally rooted in our perceptual experience. Given the evident ties between Johanna von Monkiewitsch’s work and Minimal Art, these phenomenological observations offer an initial framework for analyzing her sculptures, or at least one way to apprehend them.

The light projections then lend an additional degree of complexity to the arrangement of the individual works in the sculptural ensemble, because these are not simple spotlights but video recordings of sunlight across a white surface. This video is projected partly onto, partly next to the individual elements and defines a geometric, more or less rectangular area whose size conforms to the 16:9 aspect ratio of modern film and television formats. The areas of light, which are brighter than the rest of the exhibition space, stand out clearly against the wall, the floor, and the blocks. This has the effect of altering our perception not only of the surface colors but of the very materiality of the sculpture’s elements. In some ways this resembles the effect of Wolfgang Tillman’s Paper Drops (2001 present), a series of photographs on glossy paper, or Barbara Kasten’s Polaroid series Construct and Metaphase (1979–1986). Both artists used a similar procedure for illuminating material or things, in Tillmans’ case paper and in Kasten’s work a precisely arranged ensemble of Plexiglas and mirrored or metal elements. The resulting photographs capture both the light reflections on the materials and their shadows. In other words, the light is what makes both the material and the photograph exist for us. What emerges is an “imprint” of the abstract properties of light and shadow. It is no coincidence that similar reflections on the medium of photography can be found in various works by von Monkiewitsch, including the series of pigment prints 10.16.2013 / 10:45 and 10.16.2013 / 10:47, Venice, Los Angeles, both from 2021. How to depict light while making the full spectrum of its “capabilities” perceptible – including the metaphysical – is one of the questions that runs through her artistic practice.

In the series of sculptures on view in Bremerhaven, a video projector allows von Monkiewitsch to explore additional perceptual possibilities, with the light emitted by the device and that captured in the video coinciding. The bright luminosity produced by the projector tends to flatten the light or even make the relief sections of the works or their edges disappear. This is what happens, for example, in Calle Correr, where the foam block lying on the floor and the white wall behind it seem to merge into a single volume. The many reflections created by the crumpling of the plastic film encasing the foam contribute further to distorting our visual understanding of the object. In Black Out, the black fabric seems to sink into the illuminated area without the eye being able to focus on it. In Square, the projection directed at the two foam blocks of slightly different shades and thickness impedes our grasp of their material properties. Approaching them, one wonders if they are hard or soft, light or heavy, filled or hollow. In other words, each of the sculptures undergoes a dematerialisation effect that undermines perception. This reminds me of installations by James Turrell, the light artist par excellence, and his preoccupation with dissolving the boundaries of space, either by creating a luminous blur or by playing with architectural perspectives. It is important to note that the light projected onto von Monkiewitsch’s sculptures often varies considerably in intensity, whereas a spotlight provides constant illumination. The video, shot outdoors, transmits in loops up to thirty minutes long the fluctuations in light caused by the passage of a more or less dense veil of clouds across the sky, a technique that played a central role in von Monkiewitsch’s exhibition at the Kunstverein Bochum in 2021. This arresting of time is what gives the projection its complexity: it is simultaneously a witness to the present moment (the light of the video projector), to the memory of a specific time in the past (the moment when the sunlight was filmed, captured by the video), and to the passing of time (three minutes of filmed light). The sculptural arrangement is thus inscribed in its own time frame, which hence becomes the subject of the work. The visible wave movement brings the entire ensemble “to life”, like a kinetic sculpture that cleverly tricks the eye. The “magician” has done a splendid job.

Johanna von Monkiewitsch’s light sculptures generate a confrontation of solid with liquid, a backandforth between matter, time, and space. Paradoxically, it is dematerialisation, produced by the intensity of the light but also by its undulations, that breathes “life” into inanimate things. The merging of the elements, along with the overturning of what we think we know about matter and its properties, lead to a kind of perceptual confusion. Subtly but surely, this bewilderment penetrates from our pupils to our synapses, opening a rift that touches something that goes beyond ourselves and demands that we let go of our habits of seeing. Perhaps it is an exaggeration to say that this rupture is an expression of something spiritual, but for me at least, it is intimately connected to a sense of the mystery of our existence.

-Oriane Durand

(text from the catalogue Johanna von Monkiewitsch Arise, Kettler Verlagv2022)