Artist: Joep van Liefland

Exhibition title: VIEWING DAYS

Venue: Tick Tack, Antwerp, Belgium

Date: September 18 – November 21, 2020

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Tick Tack, Antwerp

Note: Exhibition floor plan is available here

Technology cares little about memory. Technological devices can provide memory–or what we now call data storage–but technology in and of itself doesn’t remember. Progress and innovation are the key terms of technological development. Once there is a newer and more apt technological device or tool, we tend to discard the old one. With the radical shift from analogue to digital technologies, many apparatuses have become outdated and have lost their utility. The list is long: telephone, fax, television, audio cassettes, cd’s, VCR video, slide projectors, to name but a few. Some of us turn nostalgic when they retrieve exemplars of these old machines and instruments, but very few effectively keep and collect them. For the artist Joep van Liefland, these obsolete appliances and equipment serve both as medium and material. Over the past two decades, the Berlin-based artist has avidly used derelict technological devices to create often trashy, room-filling installations, but also combined them to produce sculptures, light boxes and wall reliefs. The vernacular aesthetic of VCR technology also served as the basis for wide-ranging graphical experiments in both collages and prints.

VIEWING DAYS, the artist’s first solo exhibition in Belgium, presents a unique opportunity to enter the simultaneously dark and humorous universe of van Liefland. For his solo presentation at TICK TACK, van Liefland has opted for an immersive installation that occupies the three floors of the gallery. In addition to the ground floor and the duplex level, van Liefland also decided to use the basement, allowing him to grant each space a different treatment and above all, a distinct atmosphere. The remarkable architecture of TICK TACK, in particular the two-story-high window of the ground floor of the Léon Stynen-designed condominium, provided the starting point. Van Liefland reads the surface of the glass vitrine as an atypical interface: a screen that mediates between the exterior, public space of the city and the inner, private space of the gallery. He conceives the exhibition as a peek behind the interface as if it was an entry into the backstage or ‘coulisse’ of the apparatus, a spatial exacerbation of the inner workings of digital machinery and the processes of digital image production, distribution and consumption.

On the ground level, van Liefland covered the wall with a painted mural of the RGB pattern. Not unlike the striped pattern of Daniel Buren–allegedly van Liefland’s stripes are an equal 8,7 centimetres wide–the mural has been specifically devised for the exhibition space.

More to address today’s all-pervasive presence of digital imagery, in art galleries and the world at large than to reveal the institutional conditioning of the gallery. RGB is the DNA code of the electronic color image: Red + Green + Blue = Light.

Blown up to the size of the gallery walls, the RGB code turns spatial. Van Liefland’s mural eschews the production of any imagery. It somewhat triggers a dizzying effect, troubling our sense of balance and orientation.

On the first floor, van Liefland once again painted a portion of the walls, yet now, in a feverish green. It transforms the upper story into a green key room, referencing the common digital technique for mounting artificial kinds of background images. Against this backdrop, van Liefland presents two showcases, covered with blue plexiglass. Sarcophagi of sorts, they contain assorted relics of both analogue and digital image expenditure.

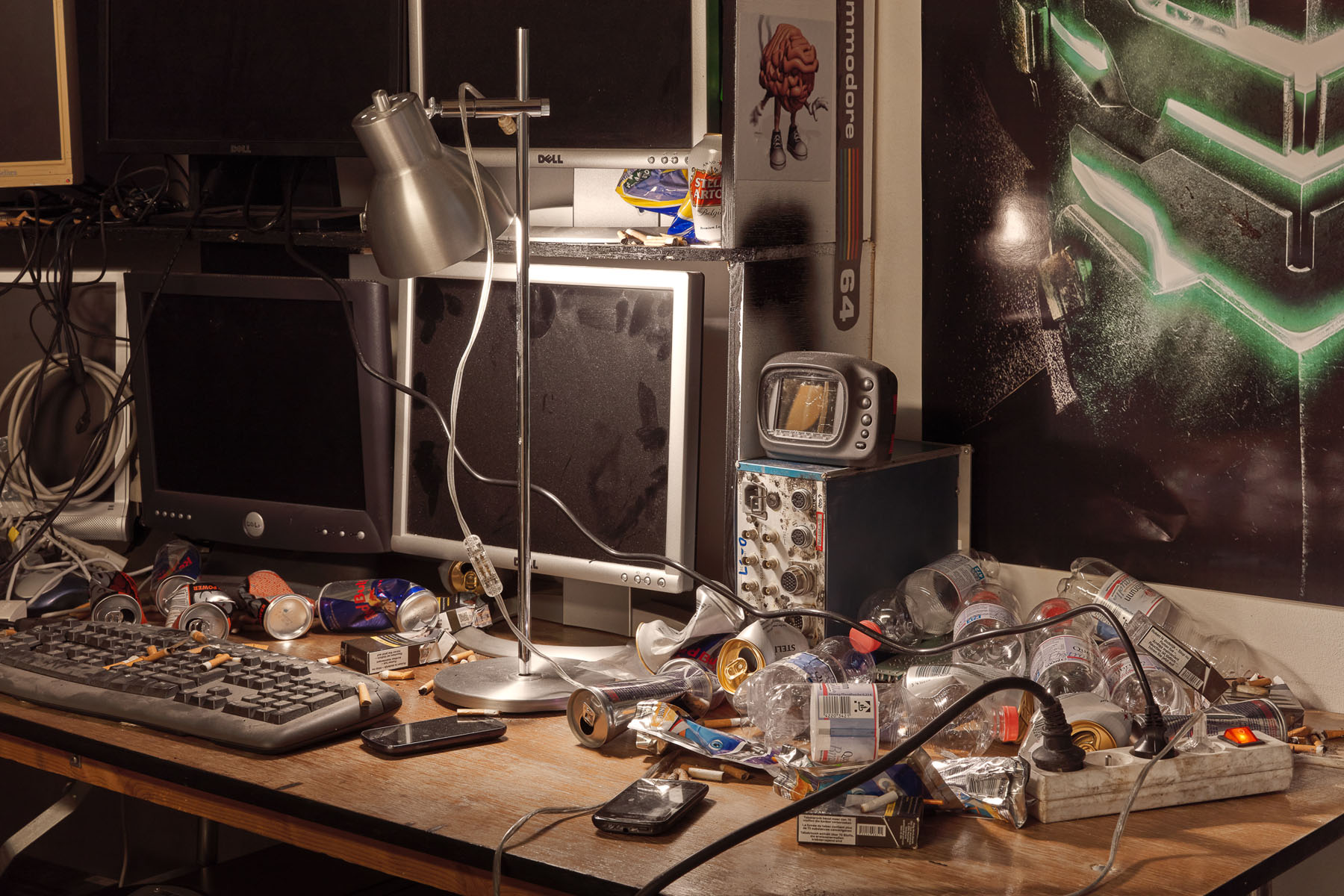

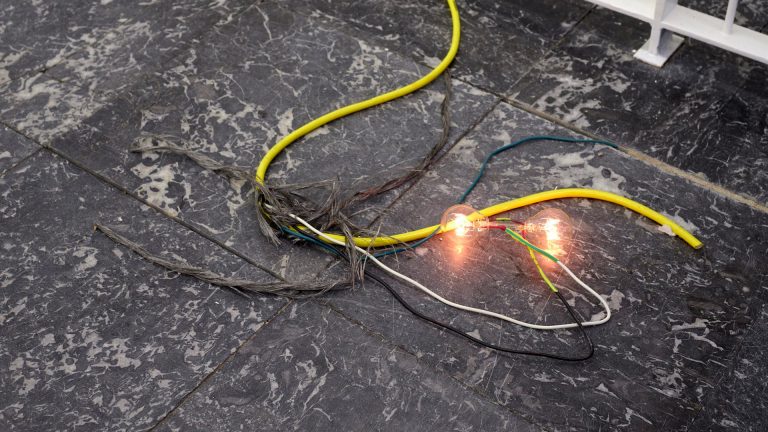

A triangular segment of the RGB-mural shows that the basement has also been taken over by van Liefland. In the gallery’s vault, the artist has recreated, after an image scored on the internet and his own bachelor experiences in the past, a digital native’s crash pad. Not unlike the source image, the room is packed to the brim with screens, computers, discarded digital gear, empty food and drink cans, as well as assorted debris. One imagines having entered one of the darker catacombs of present-day surveillance politics, holding the middle between refuse heap, masturbatory hideout, and high-technologically equipped sanctum of a dark web drudge. Only one screen works, though. With a gentle nod to the claustrophobic video installations of Dan Graham and Bruce Nauman, it presents a kaleidoscopic live-feed of the very room itself. In Francis Picabia’s Fille née sans mère [Girl Born without a Mother] (circa 1916-17), the steam engine symbolises the inevitable mechanisation of human life at the turn of the 20th century. With TeleHell VP#47 – Boy born without a mother, van Liefland intimates how fast the radical processes of digitalisation at the turn of the 21st century turn such and other more recent machines into industrial archeology.

Besides the three different space-filling installations of the gallery’s respective floors, van Liefland will also project a film on the screen that TICK TACK lowers behind the glass facade at night. Produced especially for this exhibition, Untitled (Inverter) stems from the artist’s permanent harvesting of images from the internet, consisting of sci-fi book covers and other types of images. Although van Liefland has used some of these images in printed form for paper collages in the past, Untitled (Inverter) is the first work to use these in a projected form.

More out of a deep fascination for the radical break then out of nostalgia, the digital turn has implied van Liefland acts as a media archaeologist of a sort, if not a conservator of analogue recording and playback technology. With VIEWING DAYS, van Liefland hints at the precarious temporality and dazzling speed of technological change, as the artist reaps from the ever-growing trash belt this process yields.

-Text by Wouter Davidts