Jill Mulleady’s work is haunted by ghosts. Present ghosts, past ghosts, ghosts of ruins and ghosts of people and ghosts of creatures; and also the ghosts of ideas, the ghosts of images. The ghost is both an expression of an idea, a personality, a feeling, and a monster that appears in familiar context, bringing as Hamlet might put it, “airs from heaven or blasts from hell.” The ghosts force us to make a choice that we might not otherwise want to make. Such a haunting is personal, present, examined as an outgrowth of the self in Fiamma Rossa, at Sant’Andrea de Scaphis.

Mulleady’s ghosts occasionally explicitly reference the past. In Nymph (2024), a figure examines a flower seemingly for the first time, understanding it in detail. Mulleady uses the work to explore the tension between the numinal and lived reality: the image is from Böcklin, recalling Mulleady’s Swiss roots, but in the flowing of silk and sunlight, fixed in an instant of examination, it transforms into more than just recollection.

Still Life on Ice (2024) takes up a similar problematic in the form of fish, recently dead and glittering in the Tangier sunlight. Are they alive or dead? In this still-life (or un-still-life) the interplay between life and death, the vital and the institutional form a double-bind, one in which Mulleady puts our relation to the history of art and painting under the microscope.

Alive or dead? The very same question is posed by the sculpture Young Roman (2024), which sits in front of the church altar. The figure appears to be rising and yet its body is also turned face-down, weighed down by a sheet that confines carnal identity to oblivion, perhaps heaving its final breath.

The Italian director Dario Argento looks at a length of rope during the shooting of “Suspiria” in Dario (2024). His saturated films are famous for their exploration of horror, shadows, haunted minds and the supernatural. Mulleady has always been fascinated by his work, and she traveled to Rome earlier this year to interview the director and paint his portrait. The tension between storytelling and oblivion is emphasized by Argento through his relentless build-up of suspense, a crescendo that is shattered with the utter emptiness provoked by violent death.

But Mulleady’s vision reminds us that morbidity is not always the answer to such questions. In Seascape (2024), a shoal of fish, squid, octopus, dolphins and so on form a firmament around a ruin—a temple perhaps?—reminding us of the nomenclature of Sant’Andrea de Scaphis. The church initially served as a place of worship for those in the port, the folk of the scafi, the little boats that plied the Tiber, bringing fish and goods to the city of Rome.

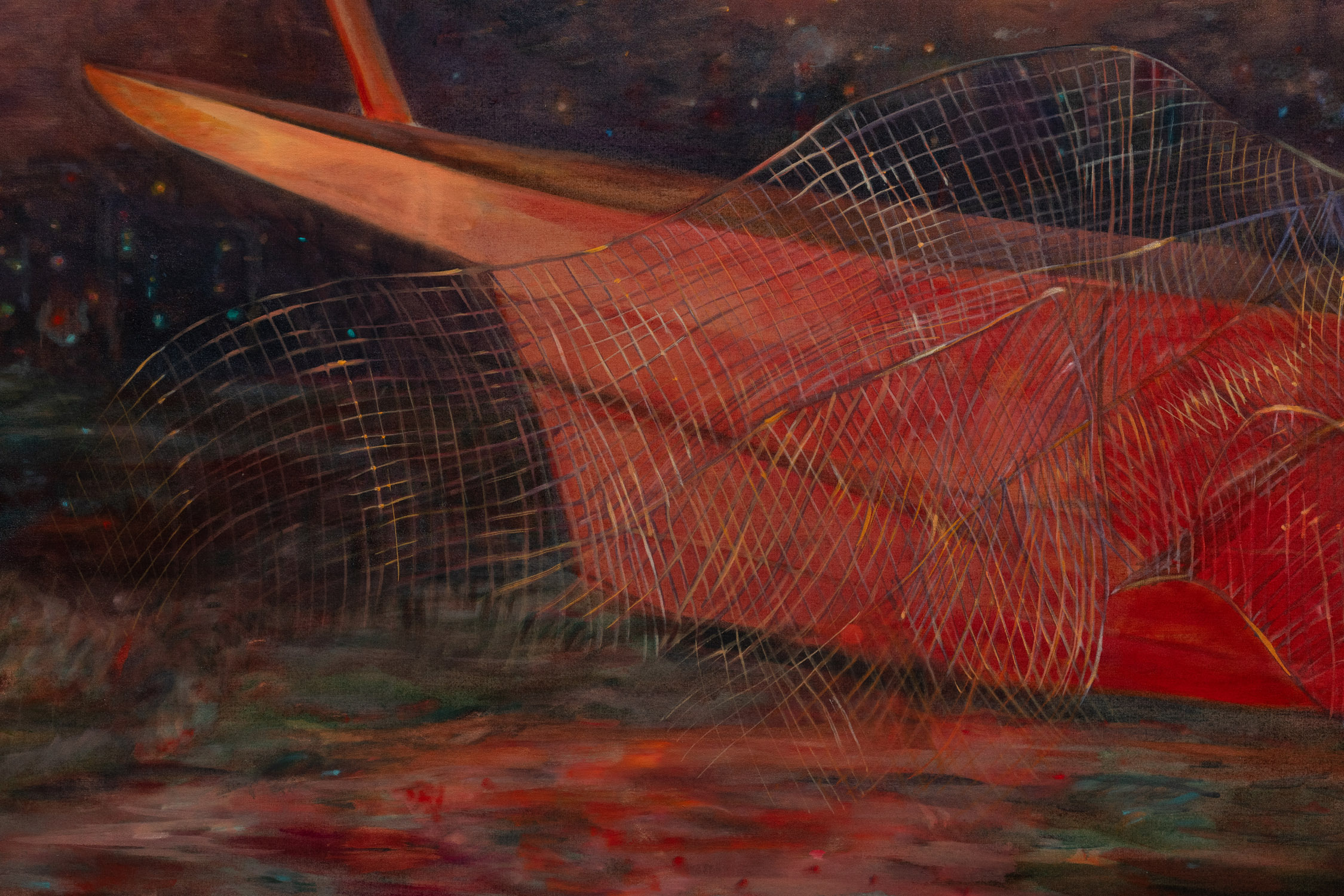

Fishing makes another appearance in Pesca a la Encandilada (2024), in which Mulleady recalls fishing in her native Uruguay, using a bright flame to lure fish to their death. For a moment before their slaughter, she appears to say, they are more alive than ever, entranced by the beauty of the dancing flames. The Wheel of Ixion is for a moment stilled. A synecdoche for the strategies used during Colonization, the painting permits itself to revel in the tension between illusion and demise, an instant frozen before an inevitable negation: Mulleady’s work asks why this dance can’t last forever.

— Nicolas Niarchos