Artist: Jannis Marwitz

Exhibition title: Narch till June / Närz bis April

Curated by: Oriane Durand

Venue: Dortmunder Kunstverein, Dortmund, Germany

Date: November 23, 2019 – February 9, 2020

Photography: Simon Vogel / all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Dortmunder Kunstverein

For Narch Till June / Närz bis April, Jannis Marwitz‘ (*1985 in Nuremberg, lives and works in Brussels) first institutional solo exhibition in Germany, the artist presents all new paintings and drawings from 2019, and one work from 2016.

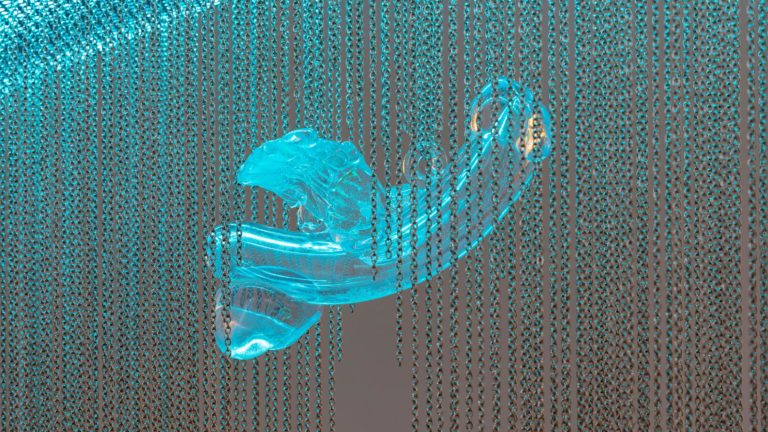

With his selection of figurative motifs, Marwitz draws an arc of art history departing from antique reliefs and Baroque compositions up to digitally animated images. His lavish paintings depict rich scenes painted in oil and tempera across a range of canvas sizes. Besides two self-portraits and a portrait of the artist Christiane Blattmann, the subjects Marwitz chooses seem inspired by mythological tales. The works are all reminiscent of old masters painting techniques, for example, the way Marwitz articulates bodies, animals, landscapes and objects via clear contours. You recognize what is depicted at first glance – but appearances are deceptive: the goose’s wings within Die Frösche (The Frogs) are as strangely shaped as the bodies of the Hercules-like figures in Poacher and Poachers – are these muscles, pulsating skin, or paint melted onto the canvas? Does the male figure whose tongue is drawn by a goose float in the air or does she stand on the ground helped with an invisible foot? Scale, color choice and the overlapping of details are disruptive factors. Marwitz plays with proportion, illusion and the means of language: What appears to make sense and what doesn’t; what is realistic and what is not? How does the eye translate the depicted into our realm of experience, and at what speed is this information processed?

Seeing – or rather, looking – is a reoccurring topic in Marwitz’s works. This motif appears in almost all of the paintings here and is further reinforced by their hanging, allowing the paintings to communicate with one another. The figures within seem to look out at the visitors or at each another, formally referencing the next representation, where in turn some element within the image is found to occur in another painting, whose color palette subsequently refers to another painting, etc.

Marwitz’s arrangement in the room not only overwhelms the viewer’s gaze via the strong reciprocal references (in form, content and color), the works also give the impression that an entire image databank has been stored on the canvas. This density and compactness can also be found in his painterly gestures and color choice: the intensity of dark blue, pink, and acrid green suggests a dark and nearly toxic, but also sensual feeling.

Beyond the painterly virtuosity in evidence here, what is special in Marwitz’s work is the sharp and suggestive conceptual connection between a traditional painting technique and a history of images spanning centuries alongside the continually topical theme of image production in the digital age. With his paintings, he creates an allegory of data storage similar to the internet: a container for information, a space of both parallelism and hypertrophy.

Between this parallelism and hypertrophy, Marwitz develops an intensity of painting that exaggerates, that merges into one another, that at times borders the ugly and hurts the eyes. The artist is not afraid: like Orpheus, who descends to hell to save his lover Eurydice, he descends into darkness to reach to the boundaries of painting.