“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms…”

(Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or, Life in the Woods, first published in 1854.)

“Into the Wild” is an exhibition that unfolds across space and time. It transcends conventional boundaries, embracing both visible surfaces and hidden territories, traversing tangible paths and inner journeys. This sensory and symbolic exploration delves into the profound—often conflicted yet always vital—relationship between humanity and nature.

In an era defined by the Anthropocene, where the human footprint voraciously reshapes natural landscapes and disrupts ecological and cultural balances, the exhibition becomes both a space of resistance and contemplation. It invites a return to primordial instinct, a rediscovery of the wild as an inner dimension—an echo of an ancestral past that still pulses within us.

This call is not a fierce summons but a primordial reverberation. It explores the unknown—physical, emotional, spiritual—forming a bridge between two seemingly irreconcilable hemispheres: the self-referential logic of our hyper-digital age and the archaic, unconditional force of the earth. In this suspended space, opposition yields to dialogue, and distance becomes an invitation.

“Into the Wild” is neither a nostalgic return to creation nor a celebration of the Romantic notion of Nature—rooted in Sturm und Drang—that idealizes it as an overtly utopian realm. Instead, it calls us to listen to the wildness within us: pulsing, untamed, alive, and authentic. The wild is presented not merely as a physical location but as a mental and emotional horizon—a real condition of being and an irrepressible existential drive that resists the bleakest forms of conformism and hyper-rationality.

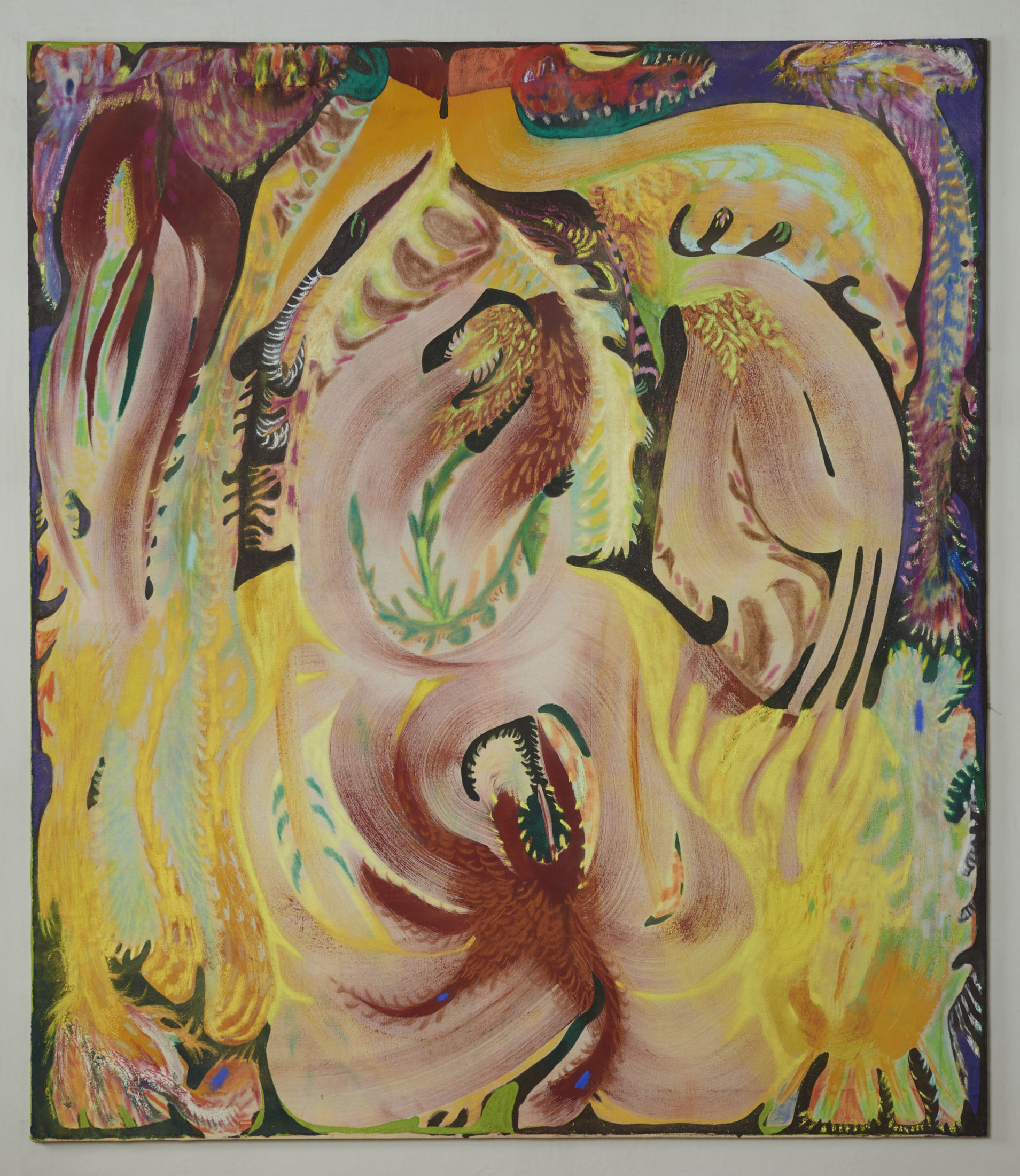

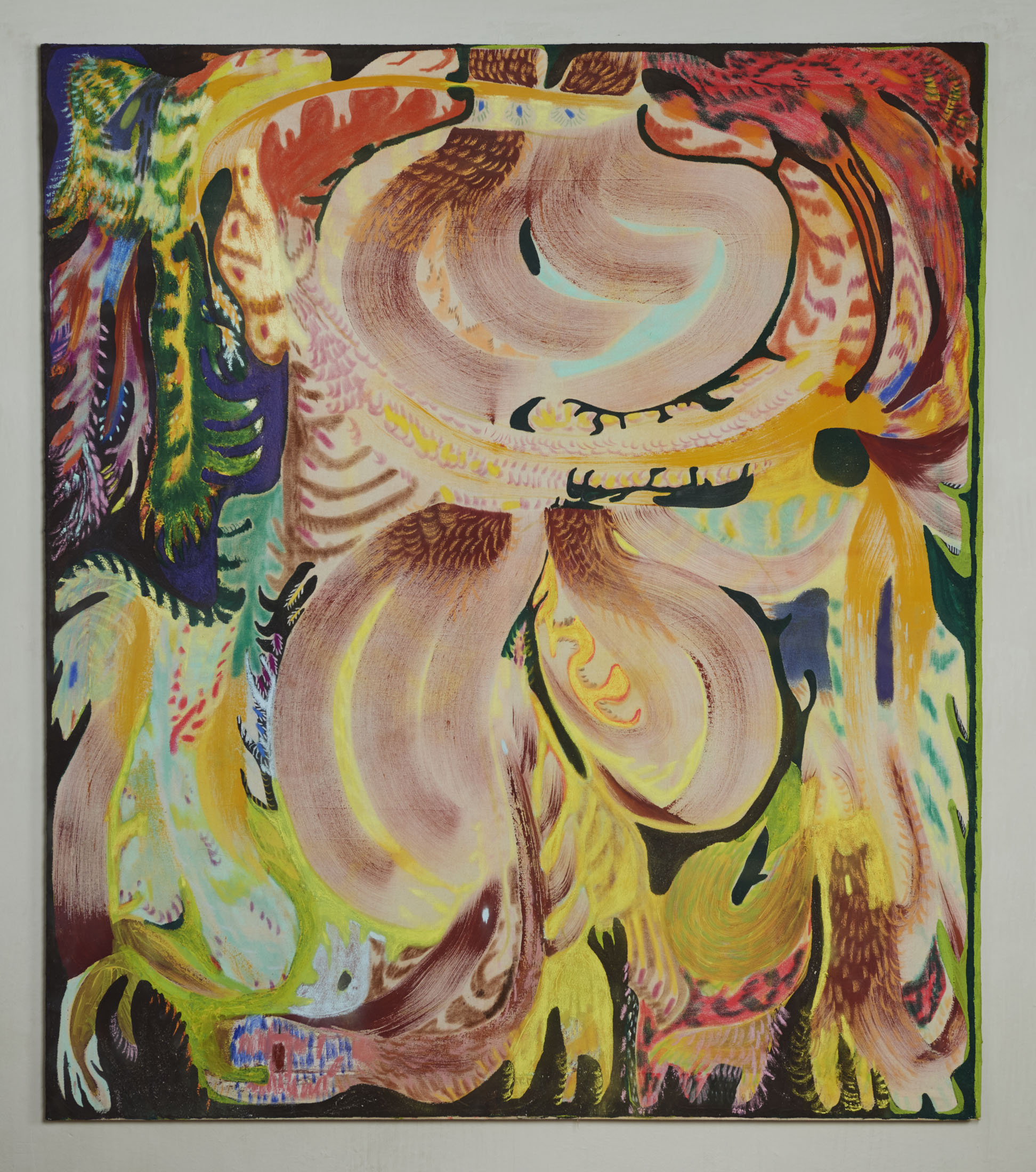

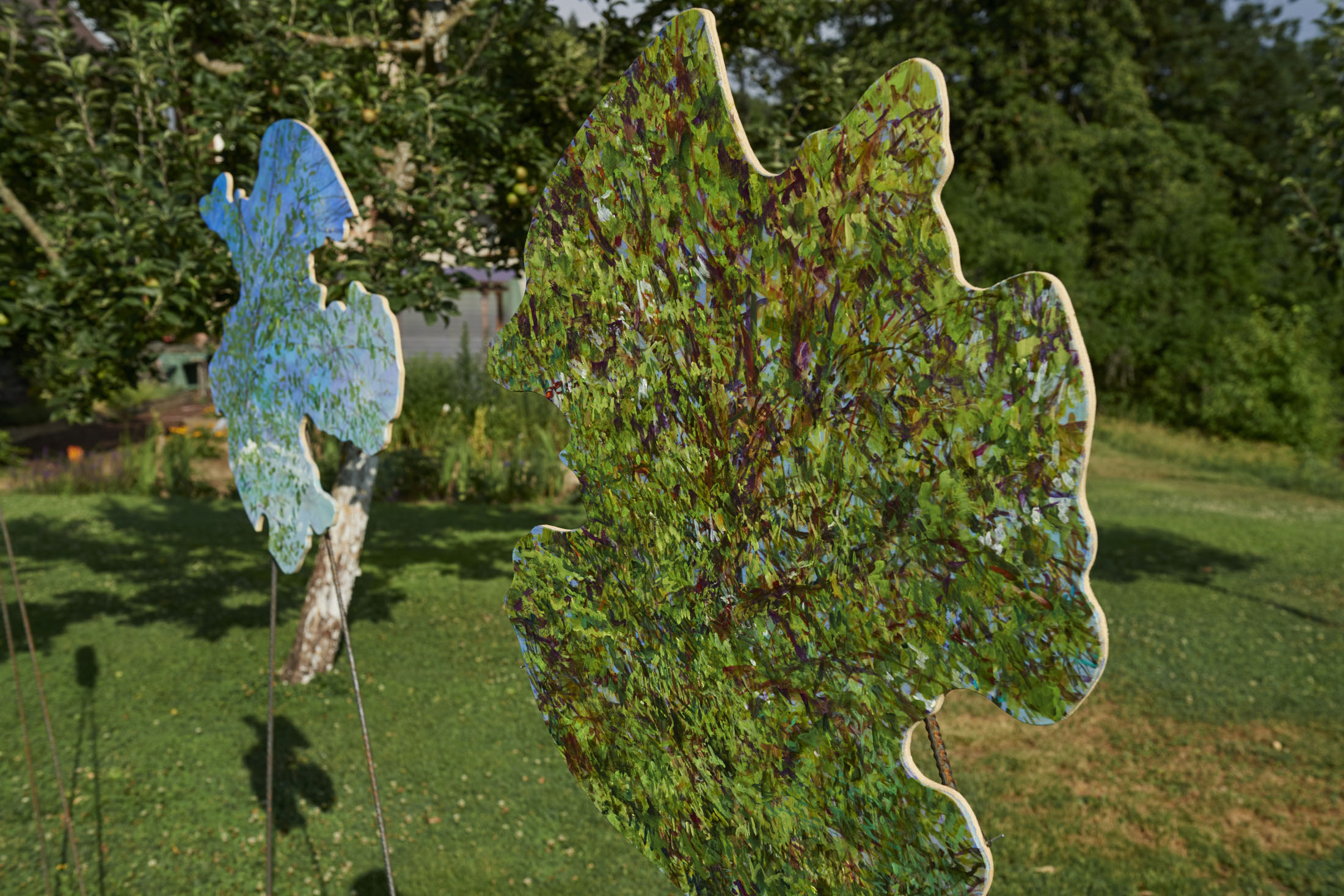

Through a diverse and dialogic body of work, the participating artists offer visions spanning the organic and the artificial, the abstract and the symbolic. Their expressive languages range from site-specific installations and material experimentation to painterly evocations and sculptural gestures. This multiplicity reflects varied approaches to nature as a total and transformative experience.

Each work—by Markus Orsini-Rosenberg, Daniel Spivakov, WKND Lab, Antonio Bokel, Magda von Hanau, Melania Toma, Eva Schlegel, and Erwin Wurm—expresses a tension between the human desire for control and the irrepressible vitality of the natural world. Nature’s force, both violent and tender, is conveyed through a rich visual language: abstract and figurative forms, colors shifting from somber to vivid, surfaces alternating between slick and inviting. Reflections, immersions, and a fusion of diverse materials and techniques deepen this complexity.

The structure of Meiselberg Castle—with its distinctive historical and architectural layers—acts as a resonant chamber for these works, amplifying their poetic and conceptual impact. In the dialogue between interior and exterior, built space and surrounding landscape, a temporal short-circuit emerges. This evokes Nietzsche’s concept of the “eternal return,” inviting us to recognize that every escape into the wild is, ultimately, a return to what we have always been.

Looming in the background of the exhibition is the thought of Jürgen Habermas, a philosopher of striking contemporary relevance. In his essay The Future of Human Nature, Habermas addresses critical themes such as eugenics and the complex relationship between humanity and nature with rare clarity. He views nature—both human and external—as integral to the processes of emancipation and rationalization in modern society. Yet he cautions that, if misunderstood or mismanaged, nature can become a constraint—or even an obstacle—fueling social and ethical tensions.

This reflection culminates in a powerful image: our condition as beings deeply rooted in the natural world yet engaged in an ambivalent, ongoing attempt to transcend it. This dualism invites a rethinking of our relationship with nature—not as domination or control, but as a complex, responsible dialogue that balances respect, awareness, and harmonious transformation. Within this tension—between separation and belonging—the radical nature of our bond with life emerges, underscoring the urgency to reimagine our place not merely as part of a broader equilibrium but as conscious stewards of this vital relationship.

“Into the Wild” is an invitation to conscious surrender: to strip away the hypertrophied ego, abandon sterile hyperconnection, and escape the relentless industrial noise of modern life. In this suspended space between imagination and matter, nature ceases to be a distant elsewhere or passive backdrop. Instead, it reveals itself again and again as an essential and intrinsic part of our being. As Henry David Thoreau—one of the earliest to recognize the regenerative power of wildness—reminded us, “In wildness is the preservation of the world,” and with it, the preservation of humanity itself.

In this spirit, it may be time to resurrect Herbert Marcuse’s incisive critique of the “happy consciousness,” from One-Dimensional Man: a condition of manufactured contentment that numbs awareness of alienation and cultivates a shallow euphoria destined to unravel into disquiet. Following Marcuse’s call for intellectual vigilance, “Into the Wild” summons us to reclaim freedom—not as consumer choice, but as emancipation from artificially constructed and imposed needs. In an age increasingly seduced by the illusion that human progress depends solely on technological acceleration and material accumulation, it becomes imperative to attune ourselves—even amid the din of the present—to what endures. To borrow the words of Wisława Szymborska: we must listen to the silence of plants.

Domenico de Chirico

Milan, 24 June 2025