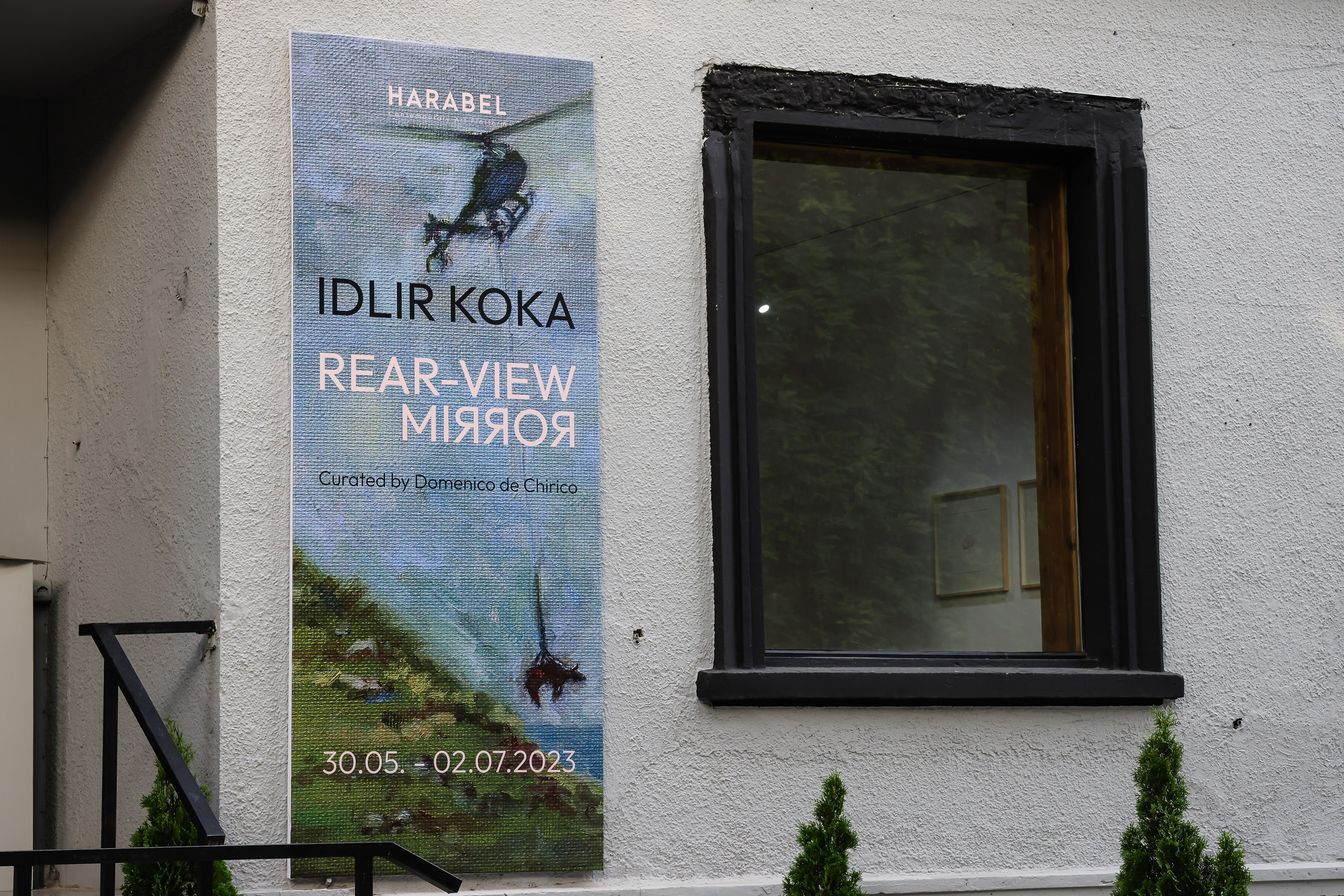

Artist: Idlir Koka

Exhibition title: Rear-view mirror

Curated by: Domenico de Chirico

Venue: Harabel, Tirana, Albania

Date: May 27 – July 29, 2023

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Harabel, Tirana

“The voids of oblivion do not exist.

No human thing can be completely erased

and there are too many people in the world for certain facts not to become known:

someone will always be alive to tell.

And therefore nothing can ever be “practically useless,” at least not in the long run.

Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, 1963.

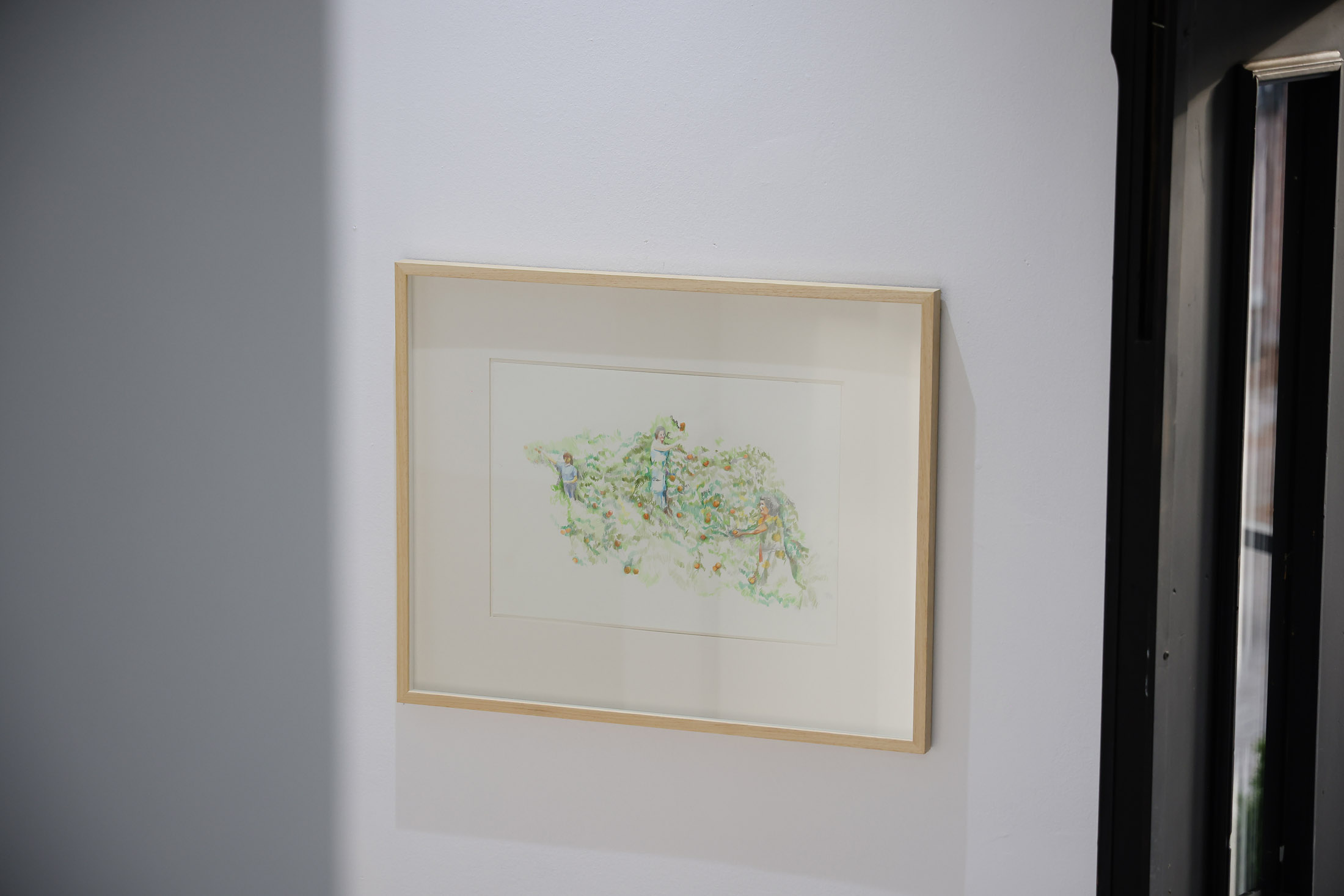

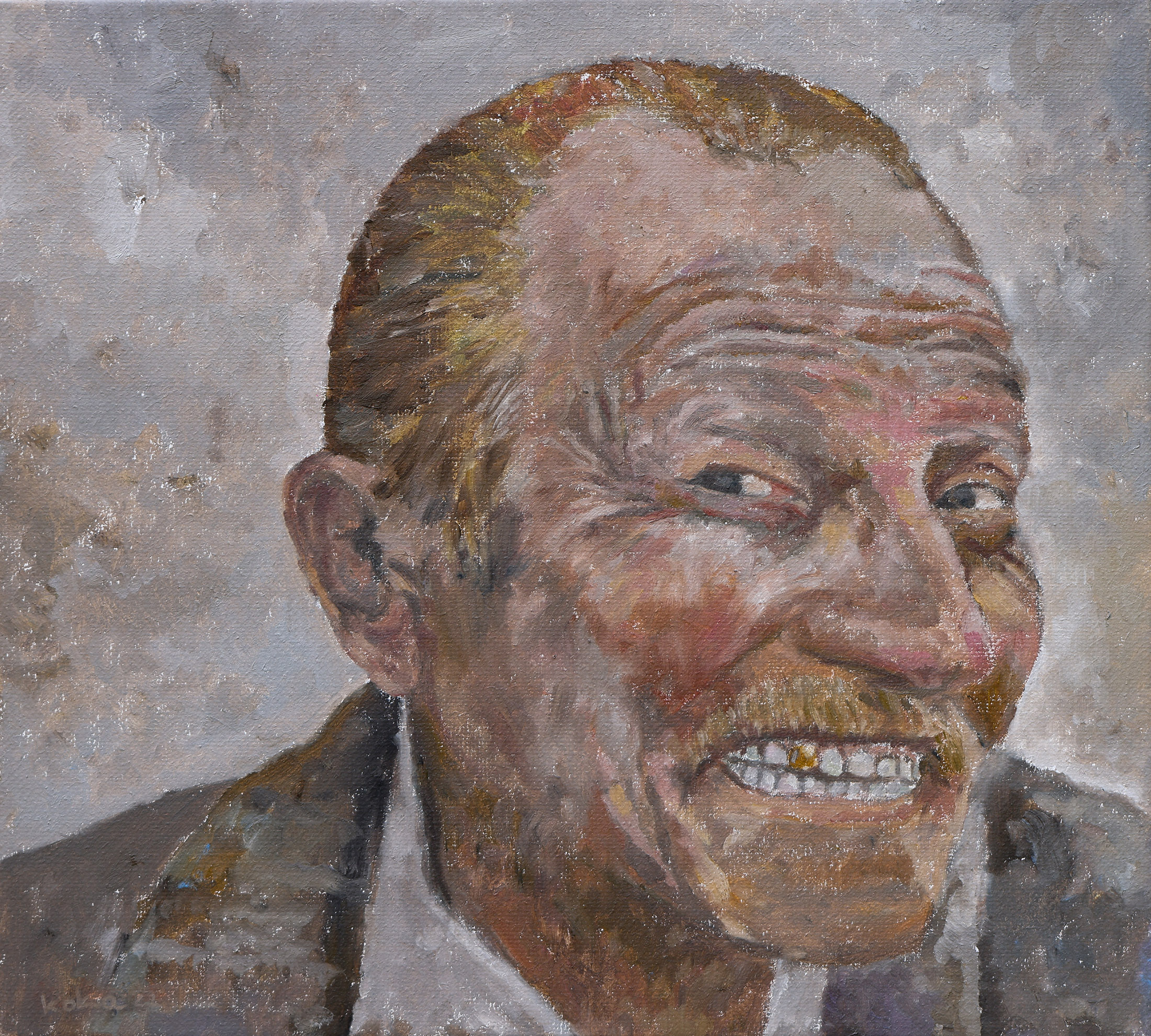

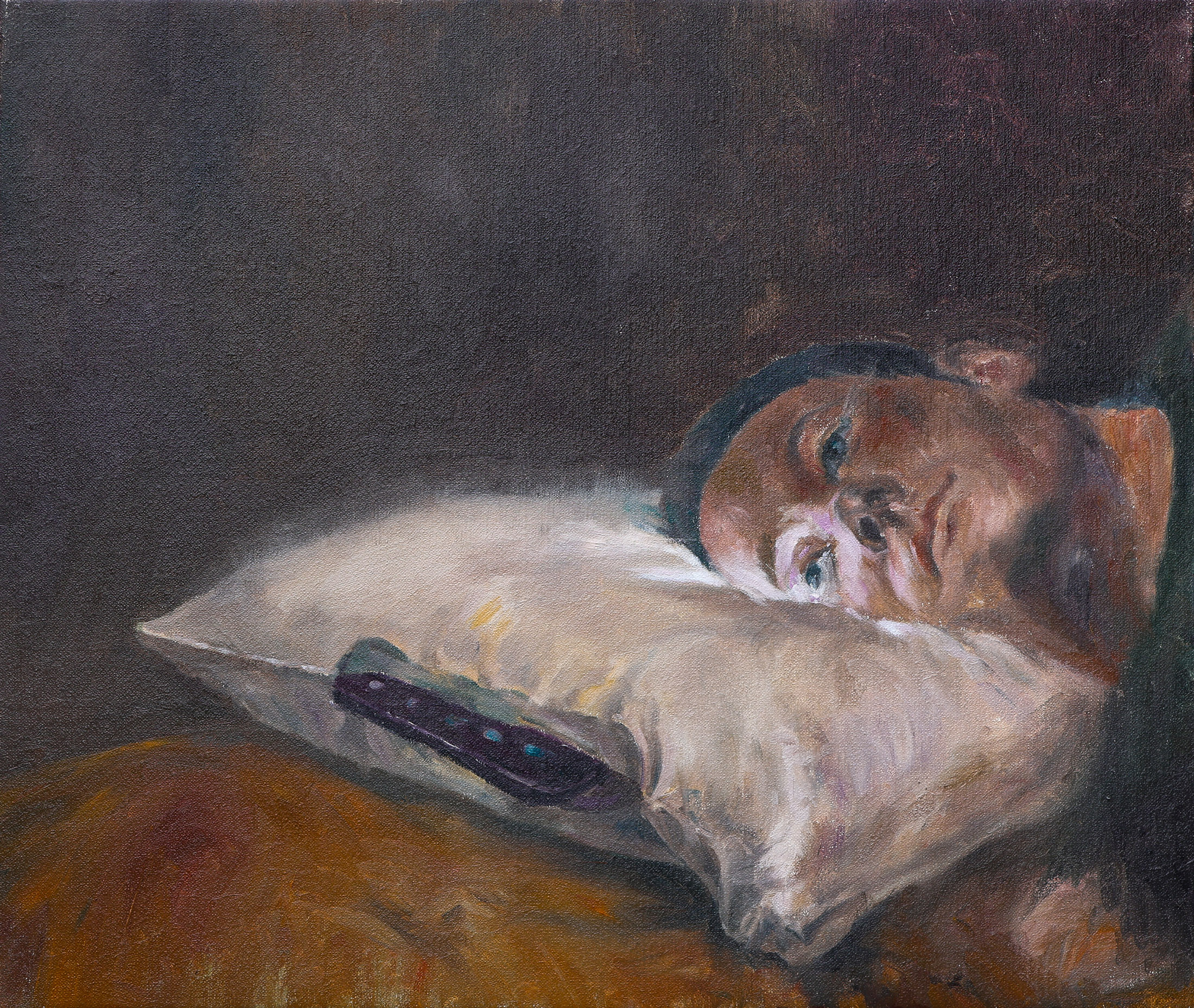

Standing in front of the soft and melancholic, persuasive and at times ironic canvases of Idlir Koka, essentially means becoming part of a sharp dialectical game, a double vortex of references that it’s rooted in a particularly fruitful ground that presents itself at the same time as historical and emotional, yet placidly impartial.

It is a mirror that does not reflect something real of which it itself represents the reflection, but a mirror that reflects itself, two reflections of the same geographical root, of a humanity investigated in its variegated complexity, observed with both eyes of the present and the past or, better said, with the eyes of the present that scrutinize the present and the past at the same time, in search of all those fleeting and unrepeatable moments that leave behind the scars of what it used to be and atavistic whispers traceable in what it currently is. Koka’s extraordinary ability consists in giving the viewer this duplicity – an indefinite duet, moreover, since the gap between the present and the past is never sharply defined – not only in representing paradigmatic acts or everyday gestures, but also in the tenuous and dissolved representation of emblematic landscape scenarios.

On the other hand, the pictorial trait of Idlir Koka, being peculiarly steeped in history, is performed with mastery by outlining a sequence of stories and events whose flow of time is elegantly painted with graceful brushstrokes and calibrated colors. The collective memory, in this case that of the Albanian people, is thus praised with fragile and evanescent hints, almost as if to make its loss even more fervent and, in doing so, the artist questions, precisely, what can really be considered memory, what the identity of a nation really represents, what are the community characteristics that define such nation and, finally, what is the role of time in the evaluation of all these aspects.

Where everything seems to be questioned, the evolution of understanding human history becomes the undisputed protagonist: perhaps it is the natural progression of things that suggests substantial changes in the life habits of a nation, or is everything the result of a cause-and-effect process also dictated by what surrounds us? Relativity and comedy simultaneously become undisputed actors in a theater steeped in images that in turn smell of nostalgia and desire.