Artists: Trisha Baga, Louise Drulhe, Veronika Eberhart, Sylvia Eckermann, Gerald Nestler, Judith Fegerl, Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, Katrin Hornek, Barbara Kapusta, Marlene Maier, Miao Ying, Pratchaya Phinthong, Marlies Pöschl, Delphine Reist, Tabita Rezaire

Exhibition title: Hysterical Mining

Curated by: Anne Faucheret, Vanessa Joan Müller

Venue: Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria

Date: May 29 – October 6, 2019

Photography: all images copyright and courtesy of the artists and Kunsthalle Wien

Note: Exhibition booklet can be found here

An exhibition of the Kunsthalle Wien in context of the VIENNA BIENNALE FOR CHANGE 2019

In any society, one fundamental field in which gender is expressed is technology. Technical skills and domains of expertise appear to be divided between the sexes, shaping masculinities and femininities. Hysterical Mining gathers artistic positions that use, appropriate, and play with feminist methodologies to question and test the (sexist) breeding ground of technology in order to decode and deconstruct the ideological terrain of the supposedly objective, universal knowledge it is founded on, as well as to reinvent the relations between techno-sciences and gender.

Hysterical Mining fervently acknowledges the gendering, ethnicising, and racialising biases inscribed and embedded in technologies generally taken as “neutral.”

The exhibition thus seeks to negotiate gender politics in an attempt to resist and counter traditional dichotomies (male/female, mind/body, objectivity/subjectivity, object/subject, human/machine, rationality/fiction) that are consequential of past and current constructions of knowledge serving capital interests. Tabita Rezaire, for example, uses the arts and new technologies as healing sciences to generate shifts toward de-colonial consciousness and occidental de-centered, gender-equal and earth-bound thinking. She is particularly interested in the time- spaces where technology and spirituality intersect. The four planes of Ultra Wet – Recapitulation’s pyramid retell vital stories of feminine-masculine alignments. The work excavates the spiritual and technological understandings of pre-colonial Africa and ancient indigenous ways of life regarding energetic polarities.

The dual title of the exhibition functions on a stratum of different grounds and actively aims to push beyond dualities, the reversal and (re)interpretation of each word and their complex of intertwined connections that surpass binary assimilation. “Hysterical” (ironically) refers to “pathologies” of hysteria (diagnosed by Freud) that allegedly agitated women into frenzied states. Turning this understanding upside down, however, the exhibition rethinks hysteria as a healthy reaction encapsulating the wider types of frustration people experience with technology and above all as a positive instinctual or emotional way to sense problems. “Mining” evokes data mining and the extraction of rare earth minerals for the production of technological devices – hence referring to ideas of knowledge and value based on the accumulation of information or raw material. Within the context of the issues addressed in the exhibition, “mining” first and foremost refers to the excavation of hidden or concealed meanings or systems to bring them back to the surface.

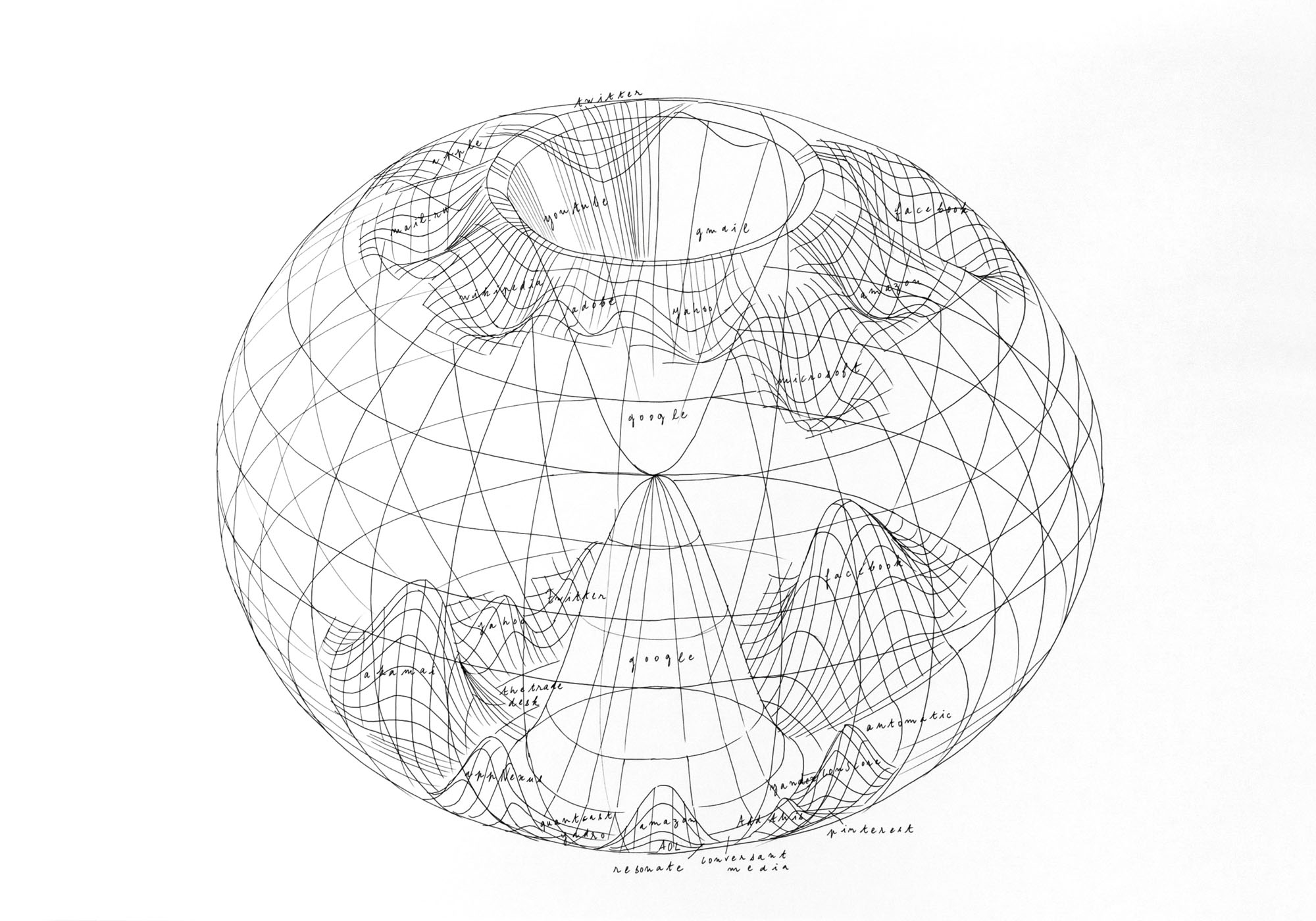

Louise Drulhe is an artist and researcher whose current practice revolves around the shape and spatial expansion of the Internet. Through a series of fifteen hypotheses, her Critical Atlas of Internet aims to develop fifteen conceptual spatialisation exercises, considering scientific spatial analysis as well as data visualisations, as keys to understand social, political and economic issues at stake in the realm of the Internet. Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni’s three season cinematic series The Unmanned portrays how technology is as much a product of humans as it is producing them, from without and from within. Hysterical Mining shows three consecutive episodes of the first season, with the background of institutional homophobia in England in the 1950s (The Outlawed), of women emancipation movements from 1920s until the 1960s (The Uncomputable), or the revolts of workers at the beginning of industrialisation (La Mémoire de Masse).

In pursuit of ways to circumvent, subvert, hack, and queer technology, the artists involved in Hysterical Mining reflect on its implications for contemporary and future forms of life as they envisage creative feminist technologies to analyse discrimination as well as to invent new rituals for co-existence. Their celebration of unknown or non-specialised approaches supplement highly informed awareness revealed of an array of technological advancements and discourses. By treasuring processes and forms of embodiment, situational and nomadic knowledge, incompleteness, as well as the use of affects and emotions in opposition to the governing, supposedly universal, and barely instrumental abstraction, the artistic contributions cultivate the exercise of feminist technophile outlooks.

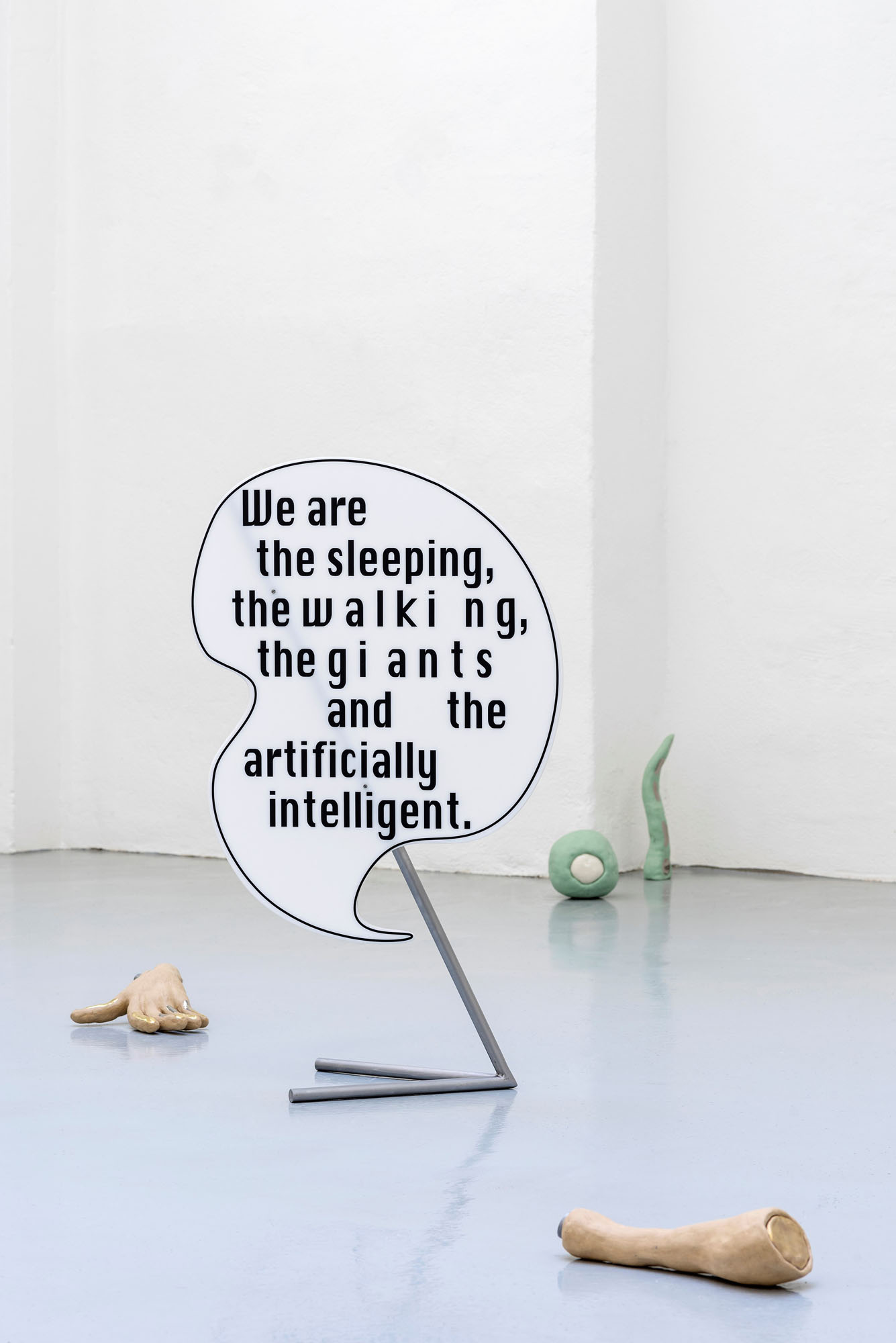

Marlies Pöschl’s sci-fi film Aurore, for instance, presents the eponymous virtual care assistant—an artificial intelligence, AI—that is seen to subtly intervene and interact with elderly people in a retirement home of the future. Addressing intimate subjects such as love, loneliness, and the question of the body, the film portrays the standpoint of a disembodied entity. The artists are not only concerned with the socio-political dimensions of the topics raised: their work makes appeals to form, shape, and texture, too, or references conceptual and minimal artistic positions to embody and coalesce with their active political engagements. Barbara Kapusta shares this perspective by asking how far we are able to imagine another body’s needs and desires. Whom and how many can we be empathic with? The partial body of her sculptural installation The Giant is comprised of limbs, eyes, and hybrid augmented body parts scattered across the floor, forming groups and alliances. Large, oversized speech bubbles dot the individual elements and depict sentences drawn from a text written by the artist: “She pauses and laughs. Her laughter is multiple voices and sounds.”

The dissolution of boundaries through fiction and imagination demarcates a space of speculation, performance, and action between disciplines, bodies, gender, species, and ecologies. The works on show bring to the fore, through various techniques of excavation, aspects that have long been hidden, disguised, or gone unannounced in order to critically address why such issues are buried from sight, and what impact these have not only for today but also for our future. Hysterical Mining exposes the transformative role and destabilising potential of new imagery and imaginaries. Translated into techno-feminist everyday practices, this renders as a fight for a more just and viable world in our techno science culture.

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Tabita Rezaire, Ultra Wet – Recapitulation, 2017–2018, Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg; Miao Ying, Blind Spot – People, 2019, Courtesy Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Gianni Manhattan, Vienna

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Louise Drulhe, Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015; The Two Webs, 2017, Courtesy the artist

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Delphine Reist, Étagère, 2007, Collection Institut d’Art Contemporain, Villeurbanne / Rhône-Alpes, Courtesy the artist; Miao Ying, Blind Spot – People, 2019, Courtesy Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Louise Drulhe, Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015; The Two Webs, 2017, Courtesy the artist, Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Gianni Manhattan, Vienna, Judith Fegerl, the kitchen was what she had given of herself to the world, 2019, Courtesy Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Trisha Baga, T BT, 2016; Untitled, 2016, Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Katrin Hornek, Casting Haze, 2018–2030, Courtesy the artist

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Gianni Manhattan, Vienna; Tabita Rezaire, The Song of the Spheres, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust: Pratchaya Phinthong, 2017, 2009, Collection FRAC Lorraine, Metz, Courtesy gb agency, Paris; Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Gianni Manhattan, Vienna; Tabita Rezaire, The Song of the Spheres, 2018, Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Tabita Rezaire, Ultra Wet – Recapitulation, 2017–2018, Filmstill, Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg

Louise Drulhe, The Two Webs, 2017, Courtesy Voyez-Vous, Vinciane Lebrun-Verguethen

Veronika Eberhart, 9 is 1 and 10 is none, 2017, Filmstill, Courtesy the artist

Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, 1922 – The Uncomputable (The Unmanned, Season 1, Episode 4), 2016, Videostill, © Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni

Marlies Pöschl, Aurore, 2018, Videostill, Courtesy the artist

Barbara Kapusta, The Giants, 2018, Installation view Gianni Manhattan, 2018, Photo: Simon Veres