Artist: Hynek Alt

Exhibition title: How Soon Is Now?

Curated by: Pavel Kubesa

Venue: Galerie NoD, Prague, The Czech Republic

Date: November 7 – 26, 2020

Photography: Michal Ureš / images copyright and courtesy of the artist and Galerie NoD

Thumb push puppets were the name of those small wooden toys in my childhood, that could be pressed with a button under the feet of the figure, as a result of which the cords running in the hollow body parts of the figure were loosened and the figure collapsed. By releasing the button, the cords were tensioned again and the figure took up its original position. Essentially, nothing else could be done with this toy. It could not really be moved or controlled like a puppet, what one could only achieve with it is that it collapsed and fell to the ground, thus rendering visible the prone structure of thin yarns holding its figure.

It’s as if Hynek Alt presses something like this wooden button when taking photographs. His works reveal the hidden, underground structures and support systems that run within us, that connect us with each other, and that operate the system under the surface in which we live. The body of our society that fetishizes appearance and productivity, is not held by a solid skeleton, but by soft structures, networks and chaotic systems interconnected along different interests. In his earlier works, Alt has also dealt with the constructedness and haphazardness of systems that are considered unquestionable. For example, in his works Clock and Tower Clock, which point to the social constructedness of synchronized time, or in the project You Can’t Change the Weather with Aleksandra Vajd, which simulates different climatic conditions in a gallery space.

In the series entitled Untiteled (Infrastructure & Beach, 2017-2020) on display at the exhibition, the life support system that operates and runs under the surface of the city comes into sight. Temporary holes appearing on the asphalt, like some sort of wounds on the city’s body, offer us a glimpse into the surprisingly impromptu, obsolete and haphazard network of cables and pipelines that sustains the various systems of the city (water, sewage, electricity etc.). It does not matter which specific detail we see, nor does it matter at which exact moment the given image was taken. The images do not appear as unique professional prints in the exhibition space, but as offset prints on newsprint paper.

Thus, it is not prominent moments and strictly composed situations that the images depict; they also refrain from pointing to individual situations, but they rather bring our attention to almost randomly selected details of an all-encompassing general structure. The horizon is not visible on the photos, therefore it is hard to guess which part is the top and which one is bottom of the image. In the holes below ground level, the directions become interchangeable, and it is as if the forces resulting from the different directions of the pressures of the underlying, buttressed layers of the ground seem to extinguish each other, somehow as the gravitational force acting on a marionette puppet and its dependence on the wire holding itself level each other off. Alt’s photos, while seemingly static, still reveal the force that keeps an entire city’s body in motion.

In his essay ‘On the Marionette Theatre’ published in 1810 by Heinrich von Kleist, he equates this driving force (vis motrix) with the soul. The essay captures the author’s conversation with a ballet dancer who explains how much more pleasure he finds in the “pantomimics” of fairground puppet figures than in well-trained dancers. The main advantage of the puppet over live dancers, he said, is the same as his disadvantage; that “it would never be guilty of affectation.” The reason for the sympathy, he said, is that during the movement, the soul (vis motrix / moving force) appears at some point other than the centre of gravity of the movement. The operator is only able to control with his wire or thread this centre, communicating the moving force exerted by him (vis motrix, soul).

In Hynek Alt’s video work Untitled (Spejbl, Ketamine, 2020), we see a 3D animated puppet. The movement of the puppet is controlled by the real movement of the artist with the help of motion capture technology, therefore, in the Kleistian sense, the puppeteer’s movements (and thus the vis motrix, the soul as well) can be translated into the puppet’s movements accordingly, so theoretically nothing forestalls the puppet’s capability of the above mentioned ‘affectation’. In this case, however, the operator cuts the imaginary cords between him and the puppet by consuming a high dose of ketamine, resulting in a loss of orientation and control, and even in the forgetting of his role as an operator.

Alt attempts to liberate the puppet and the figure of Spejbl that was created in 1920 but since then, hasn’t undergone any substantial changes, being a character who is usually just the subject of jokes, whose awkwardness makes the audience laugh, from whom no one ever expects anything, who is only a supporting character next to his own son. However, Spejbl does not take advantage of this ‘freedom’, only staring blankly and just waiting, suspended in this limbo state. As a result of the drug, a void is created between the puppeteer and the puppet, which, although it changed the paradigm of the puppet’s existence, as the puppet is no longer forced to follow the puppeteer’s movements and will, does not necessarily mean liberation.

While for the Romantic Kleist the floating of an impassive, helpless, and involuntary marionette appeared as the utopian image of human existence, in Alt’s work, the inert hovering of the liberated figure (freed from the puppeteer’s will) emerges as a kind of existentialist crisis. Alt’s Spejbl resembles more Edward-Gordon Craig’s über-marionette. In Craig’s manifesto-like essay The Actor and the Über-marionette, published in 1908, he sees the pledge of saving the theater in the shift manifested in the über-marionette taking the place of the actor. “The Über-marionette will not compete with Life —but will rather go beyond it. Its ideal will not be the flesh and blood but rather the body in Trance —it will aim to clothe itself with a deathlike Beauty while exhaling a living spirit.” The marionette is made of inanimate material, the über-marionette, on the other hand, breathes, its material is human. The über-marionette is not a puppet, but an ideal actor who can even manage to use his own face as a mask.

Hynek Alt’s series Untitled (Sculptures in the Air, 2020) also examines the relationship between man and the objects he moves and supports. Alt’s hanging collages depict sculptures and details of sculptures that are displaced from their original location for a variety of reasons. In the life of the statues, originally designed for stillness, a specific agency seems to flare up in a unique, intermediate moment, similarly as in the case of Spejbl. In the case of public sculptures, this moment is often linked to a paradigm shift, to a certain political decision, or even a change in the social-ideological system that has prevailed until then. Alt does not simply capture these significant moments, but he also renders these strikingly static objects event-like and turn their temporality into a suspended state.

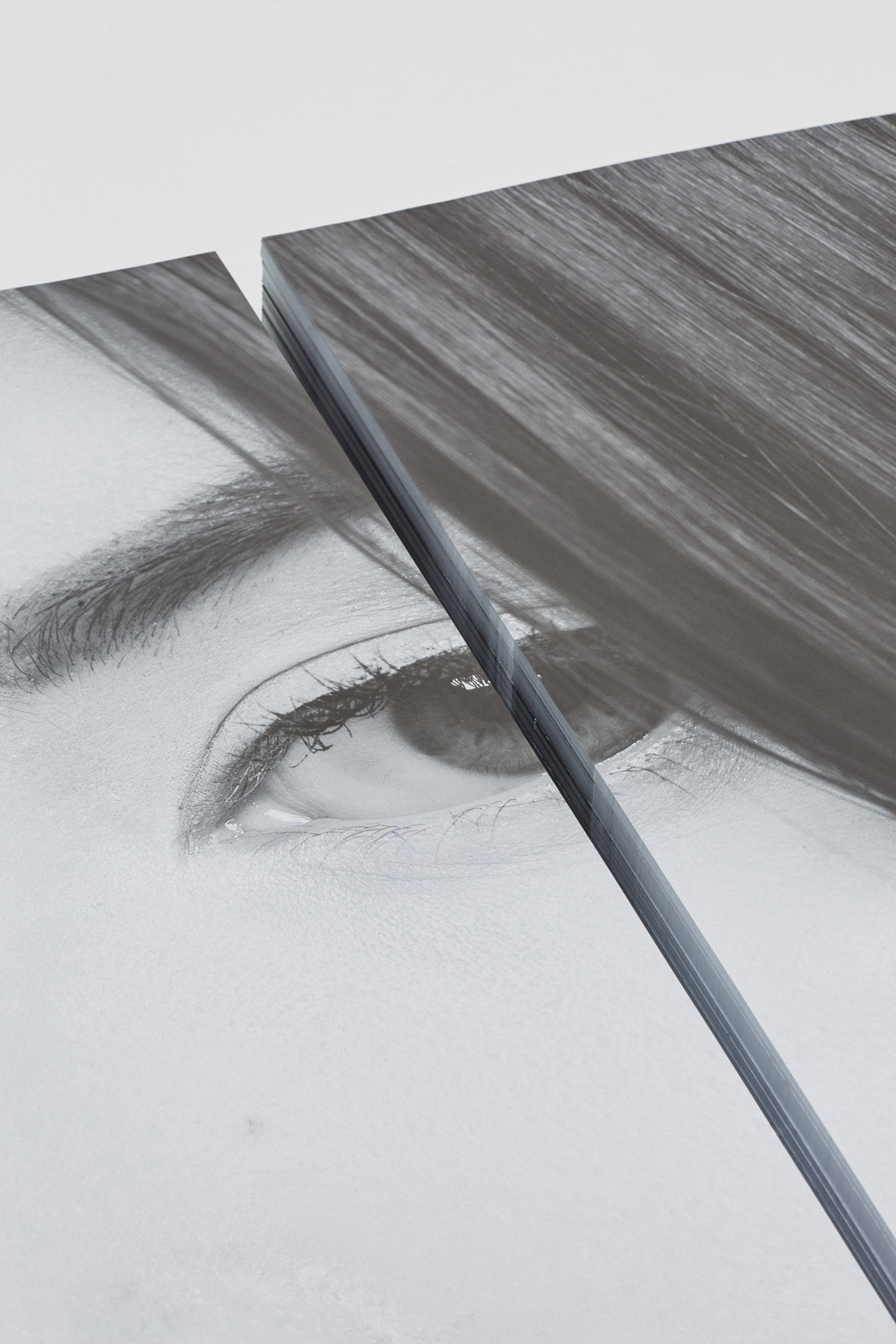

For the collages, he uses low-quality documentation photos taken by employees of the Prague City Gallery, that, besides the sculptures themselves, also depict the hands holding them, the tools and materials that protect them, and further, rather incidental details. Similarly, to the Infrastructure & Beach series, the poor photo quality is central to this work, just like in the case of the work Untitled (Lady Dee, 2020). The large portrait of the young girl also wasn’t framed and installed on the wall, but placed on the floor as posters that could be taken by the visitors of the exhibition. With this gesture, the intimate private sphere of the visitors was also channelled in the exhibition space unexpectedly, as we could possibly wonder, whether the visitor who carries a poster with them is aware that the portrait depicts the porn actress Lady Dee.

With such sophisticated perturbation, or by switching between different media, as well as with the tools and strategies of suspension, reproduction, replication, editing and highlighting Hynek Alt subtly punches a hole in the surfaces of our society propagating spectacularity, productivity and optimization. Just as the misery and vulnerability of the cult of obligatory happiness lurking behind the corporally required and monitored smiles of Amazon employees, Spejbl’s laughter also embodies the impossibility of stepping out of his assigned role towards emancipation. Alt points to the chaos stretching a few centimetres below our feet, the confusing structures and vulnerable soft systems underground, the thin wires and ropes that move the elements of reality. Alt is a puppeteer who operates his puppets by releasing, dropping, handing over, and then picking up the cords again from time to time. Controlling and playing with control at the same time.

‘Our happiness, our miseries, our beaches, or our blasted heaths — they are all within our own power to create, or destroy.’ – writes English novelist Zadie Smith in her short story of 2015, taking a giant wall ad opposite the writer’s apartment in Manhattan as a starting point with the text: Find your beach! The ideal urban (in her case, Manhattan) inhabitant, stepping through everything and everyone, moving forward in the direction of finding their own inner beach in the concrete jungle, does not care about the external or mentally fabricated obstacles, and does not allow the functioning of the outer world to have an effect on this endeavour. They move forward on this path day by day, not looking sideways, not peeking under the surfaces, and achieving the highest performance in all conditions.

“You don’t have to be high to live here, but it helps.”

-Borbála Szalai